We’re Living in the World Henry Ford Built

The creator of the Model T was also a raving bigot and a tyrant who wanted complete control over his workers. Ford is a perfect example of why rich capitalists should not run the world.

In 1915, the Ford Motor Company published a creepy little booklet called “Helpful Hints and Advice to Employes,” which outlined the expectations the company had for its workers. These did not relate to how well they built cars. The booklet explained that the company’s employees were expected to maintain certain standards on and off the job, and told them everything from what kind of houses they should live in to how they ought to raise their children.

The pamphlet showed photographs of “good and bad homes” and gave rules like “do not allow any flies in the house,” “do not spit on the floor in the home,” and “do not allow the doors or windows to remain open in the summer time without screens in them.” “Do not occupy a room in which one other person sleeps,” the pamphlet warned, “as the Company is anxious to have its employees live comfortably, and under conditions that make for cleanliness, good manhood and good citizenship.” Employees were encouraged to cultivate vegetable gardens, brush their teeth regularly, and monitor their finances carefully. Their children must not “use alleys for playgrounds.” “The Company expects employes [sic] to improve their living conditions, make their homes clean and comfortable, [and] provide wholesome surroundings,” the tract read.

Some of these points, like “do not spit on the floor,” were good advice. But these were not just amicable suggestions. Ford employed a team of dozens—sometimes hundreds—of investigators to make unscheduled visits to workers’ homes and ensure the rules were being followed. Workers were expected to comply with demands for information about all aspects of their private lives. “It is the duty of every employe to aid the investigators in every way possible in their work,” said the Helpful Hints pamphlet. “We ask you to have your papers and receipts so sorted and arranged that when the investigator calls upon you to note progress, you will be able to give him, with as little delay as possible, the information he seeks.” Investigators would monitor drinking, cleanliness, family structure, even spending habits.

Ford had received acclaim for raising wages at his plants to $5 a day in 1914, an unheard-of amount for industrial labor. But there were strings attached: workers received a base wage of $2.70. They would only be topped up to $5 if they complied with the strictures of the company’s Sociological Department. The extra was (misleadingly) called “profit-sharing,” and the pamphlet explains that “the judgment formed by the investigators” will help determine “whether the employee is worthy to receive or continue to receive profits from the Company.” Workers were warned that

“the Company will not approve, as profit-sharers, men who herd themselves in overcrowded boarding houses which menace their health,” and lamented that “investigators have found that, upon going into the homes of many employes, and particularly some of those of foreign birth, that in many cases they were living and sleeping in over-crowded rooms and tenements.” Immigrants were instructed to become “Americanized,” an achievement celebrated on “Americanization Day.” In fact, the company was emphatic that only off-the-job characteristics mattered: “There is no connection whatever between the employe’s labor and share of profits given him. His work in the factory; his efficiency and length of service; his steadfastness and loyalty are not taken into consideration in determining whether or not he is qualified to receive them.”

Unsurprisingly, the scheme is presented as being for the workers’ own good. It is described as “one of the greatest, if not the greatest, industrial sociological plan for the benefit of humanity ever attempted; entirely new in its conception and far reaching in its ultimate end,” and the pamphlet says it exists because “the Company simply wants to be assured that the profits are doing a lasting good.” Big Brother may be watching you, but he has your best interests at heart.

Henry Ford, perhaps more than any other single individual, laid the groundwork for modern industrial capitalism. His assembly lines accelerated the transition from production by individual craftsmen to high-speed, standardized mass production; the latter is often called “Fordism” after him. His Model T made automobiles affordable, reshaping society and the physical landscape. Beyond mass production, he helped to give us both car culture and suburbia.

After the assembly line process was first introduced, worker morale was terrible. Factories produced cars in a fraction of the time it took before, but the process was also dehumanizing, because it took from workers any ability to take pride in their work. Instead of having cars assembled by skilled mechanics, Ford gave laborers minute, repetitive, mind-numbing tasks. As Steven Watts writes in The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century, the definitive work on Henry Ford, “Men spent long, monotonous hours performing the same tasks over and over—tightening the bolt on a wheel housing, or lowering the car body onto the chassis, or attaching the gasoline tank. They were physically repetitive, emotionally deadening, and nearly devoid of satisfaction.”

It was hard to keep people doing this miserable work, and turnover rates were so bad that “over 52,000 men were hired every year to maintain a 14,000 workforce.” (Fortunately for Ford, deskilled workers were easily replaceable.) As the libertarian Mises Institute notes, “nine hours spent turning a lug nut is hardly an attractive job when competitors—such as General Motors[…] paid similar wages for less monotonous work.” When Ford announced huge raises, the Wall Street Journal thought Ford had gone soft and started practicing Christian benevolence, saying he was applying “spiritual principles in the field where they do not belong.” But the $5 day was not introduced because Ford suddenly had a Scrooge-like epiphany about redistributing wealth. It was because Ford needed some way to get people to keep doing jobs that were objectively mindless and physically taxing.

It worked, at least for a time. Workers put up with Ford’s intrusive Sociological Department because the wages were too good to turn down. And soon, there was no alternative to assembly line work. As Harry Braverman writes in Labor and Monopoly Capital, Ford “forced the assembly line upon the rest of the automobile industry,” because companies could not compete otherwise, and so ultimately “workers were forced to submit to it by the disappearance of other forms of work in that industry.” But even decent wages and a lack of alternatives could only keep workers in line for so long. Ford was an autocrat, obsessed with controlling every aspect of the production process personally, and by the 1930s, rebellion was brewing. As Watts writes:

Not allowed to converse, workers developed the ‘Ford whisper’—talking in an undertone without moving one’s lips while staring straight ahead at one’s work—as a way to maintain human contact during work hours. But sometimes even this subtle resistance backfired. A worker named John Gallo was discharged after a ‘spotter’ caught him ‘smiling’ with co-workers after being warned earlier about ‘laughing with the other fellows.’… [Such] incidents caused many Rouge [factory complex] workers to become ‘very bitter’ toward Henry Ford.

Ford “marshaled all of his power and resources” to ensure that his factories would never be unionized. Ford organized what the New York Times called "the largest private quasi-military organization in existence,” and historian Greg Grandin says was a “three-thousand-member goon squad[…] made up of spies and thugs armed with guns, whips, pipes, blackjacks, and rubber hoses otherwise known as ’persuaders.’” When unemployed auto workers marched on his Dearborn factory in 1932, during the Great Depression, Ford’s security guards (alongside the local police) shot them with live ammunition, killing five. Five years later, Ford security officers attacked United Auto Workers organizers who were planning to hand out leaflets at Ford’s River Rouge plant. Thanks to these strong-arm tactics, Ford was the last of the major car companies to unionize.

But, following the debut of the Model T in 1908, Ford had also become immensely popular with the public. He was called “the hero of the average American,” as Watts writes, “because he had made his fortune without ruthlessness, paid high wages to his workers, and made a cheap but reliable product.” A 1940 “survey of American workers found that they ranked Henry Ford above Franklin Roosevelt and [UAW leader] Walter Reuther as the modern American leader who was ’most helpful to labor.’” Ford was skilled at cultivating his populist image. A pacifist, Ford “view[ed] warfare as a wasteful folly,” and during World War I he chartered a “Peace Ship” to Europe that brought activists to the continent in a (futile, quixotic) attempt to negotiate an end to the war. He said his car company was “an instrument of service rather than a machine for making money.” He fought his own stockholders, calling them parasites. Ford even came close to winning a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1918, running as a Democrat.

But inside the company, Ford was essentially a dictator. The New York Times called him the “Mussolini of Highland Park,” an “industrial fascist” who wields “despotic control over the greatest manufacturing organization that the world has ever seen.” B.C. Forbes, founder of Forbes magazine, said “I know of no employer in America who is so autocratic. I know of no employer who adopts a more dictatorial attitude toward associates.” Watts notes that over time, words like “despot,” “monarch,” “fascist,” “autocrat,” and “dictator” became increasingly associated with Ford.

His ugliest trait, of course, was his virulent hatred of Jews. Even by the standards of the time, Ford’s antisemitism was so outlandishly paranoid that it’s hard to see how he could have actually believed what he was saying. He thought American farmers were being exploited by “a band of Jews—bankers, lawyers, money-lenders, advertising agencies, fruit-packers, produce-buyers, experts.” (Fruit-packers!) He thought the Jews had killed Lincoln. He prohibited engineers from using brass in the Model T, saying it was a “Jew metal.” (His engineers “used it anyway but covered it up with black paint.”) He claimed unions he hated were organized by “Jew financiers,” commenting that a union was “a great thing for the Jew to have on hand when he comes around to get his clutches on an industry.”

He was obsessed. “I never had a visit with him, at lunch or dinner, when he did not talk about the Jews and his campaign against them,” said the writer James Martin Mill. On and on and on it went. In 1921, he said “The Jew is a mere huckster, a trader, who doesn’t want to produce, but to make something out of what somebody else produces.” In 1922 he attacked the “greed and avarice of Wall Street Kikes,” and in 1923 commented “The Jews are the scavengers of the world[…] Wherever there’s anything wrong with a country, you’ll find the Jews on the job there.” He believed that “the International Jew” is the one who “starts the wars.”

Ford did not keep his antisemitism to himself. He aggressively proselytized it through his newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, which ran dozens upon dozens of antisemitic articles, put together under his direct supervision and encouragement. (Ford made his car dealerships carry it, which helped boost its circulation to 900,000.) The diatribes were eventually collected into a book, The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem, which included chapters like “Jewish Degradation of American Baseball” and “Jewish Jazz Becomes Our National Music.” (Ford despised jazz, which he thought was morally corrupting in addition to being Jewish, and he sponsored lessons in Dearborn to teach workers more morally correct dances, namely quadrilles and Virginia reels.) Strangely, Ford seemed surprised when Jewish communities were outraged. When a local rabbi returned Ford’s gift of a Ford Model T, Ford sent a puzzled reply asking the rabbi why he was upset.

In addition to being anti-Jewish, Ford was also a firm believer in white superiority, declaring:

The trouble with us today is that we have been unfaithful to the White Man’s traditions and privileges[…] We have permitted a corrupt orientalism to overspread us, sapping our courage and demoralizing our ideals. There has always been a White Man’s Code, and we have failed to follow it.

Antisemitism and racism were not Ford’s only crackpot notions. He had bizarre dietary theories, too. He thought sugar was dangerous because the crystals would slice open one’s stomach lining. He thought bad diets were the cause of criminality. “Most wrong acts committed by men are the result of wrong mixtures in the stomach,” he said. Watts notes that Ford “warned against fresh dough and said that bread should be eaten only after it has sat for a day,” “depicted fried pork, boiled potatoes, and oranges as unhealthy” (well, he got one out of three), and “advocated that people eat nothing until after 1:00 p.m. because of likely digestive problems at an earlier hour.”

Some of this is explained by the fact that Ford was proudly uneducated. He confessed that “I don’t like to read books; they muss up my mind.” When he was testifying in court during a lawsuit, he said the American revolution was in 1812, that Benedict Arnold was a “writer,” and that “chili con carne” was “a large mobile army.” Ford’s world was the auto plant, and it was the only thing he understood, although this didn’t prevent him from having opinions on everything under the sun.

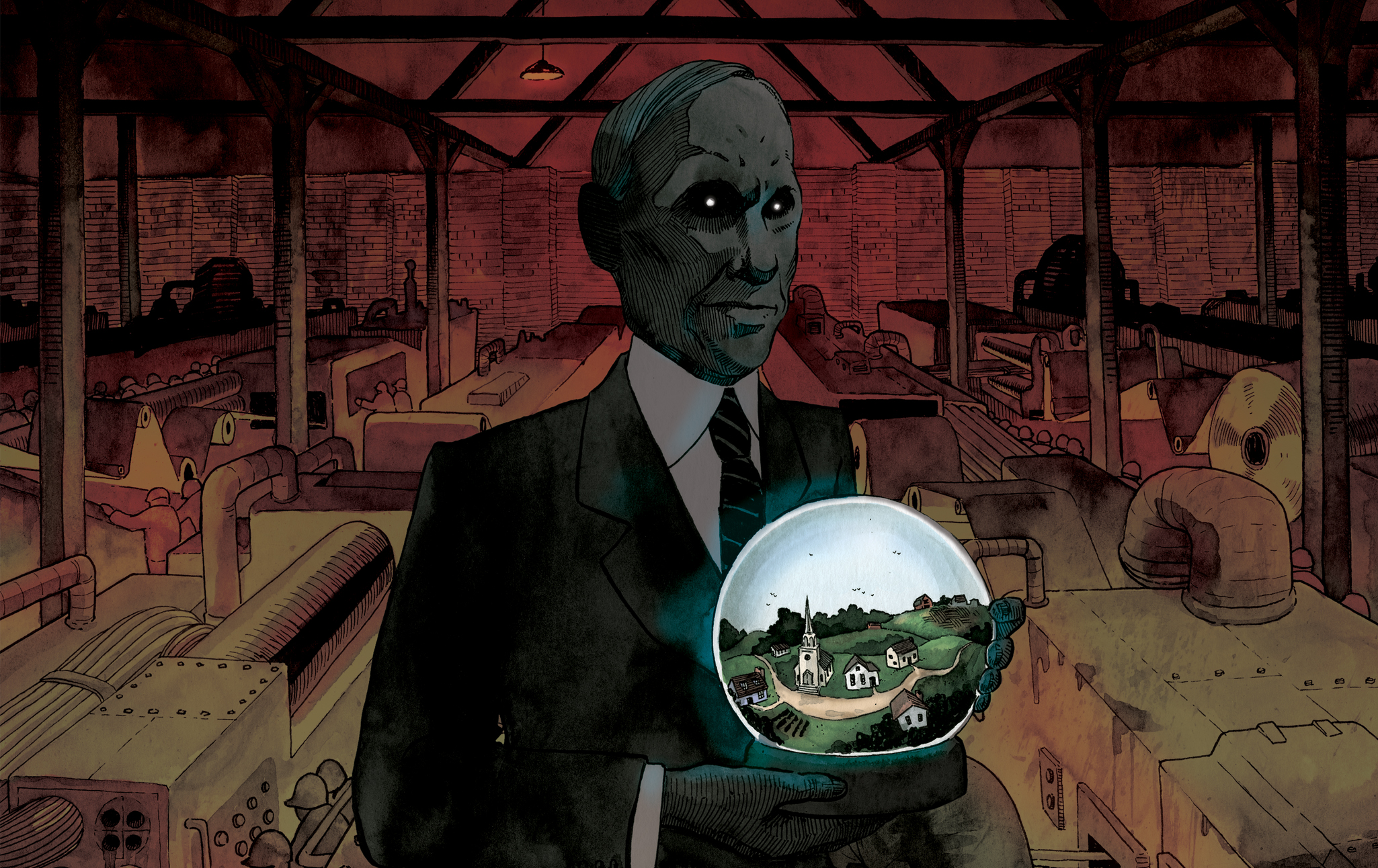

Art by Emily Altman from Current Affairs Magazine, Issue 54, July-August 2025

Most Ford buyers apparently just ignored the antisemitic newspapers in their local dealerships. But Adolf Hitler was a major admirer of Henry Ford, keeping a life-size portrait of him in his office. “I shall do my best to put his theories into practice in Germany,” Hitler said, and he based his Volkswagen on the Model T. Heinrich Himmler called Ford “one of our most valuable, important, and witty fighters.” Baldur von Schirach, who led the Hitler Youth from 1931 to 1940, testified at the Nuremberg trials:

The decisive anti-Semitic book which I read at that time and the book which influenced my comrades was Henry Ford’s book, The International Jew; I read it and became anti-Semitic. In those days this book made such a deep impression on my friends and myself because we saw in Henry Ford the representative of success…

After being sued for defamation by a Jewish labor lawyer named Aaron Sapiro, who had been named in one of the “International Jew” articles, Ford issued a public apology for his antisemitism. But Watts documents that this was entirely dishonest. In private, he continued to rail against Jews, and while Ford and his spokespeople said that Ford had had little to do with the editorial content of The Dearborn Independent, this was false. He had supervised it closely. In 1938, he accepted the Grand Cross of the German Eagle from the Nazi government.

Strikingly, even though Ford was “one of the 20th century’s most dangerous anti-Jewish propagandists,” and the ideas he espoused soon led to the mass extermination of six million Jews, Ford’s name does not quite live in infamy. Despite renewed attention to the problem of antisemitism, Ford’s name remains on his cars, the Ford Foundation, the Ford Field football stadium in Detroit, and the Henry Ford museum.

Ford accepting his honor from Nazi government officials, 1938.

During the last phase of his life, when he grew restless, Henry Ford dedicated himself to amassing historic artifacts and buildings, and assembling them in a fake Main Street near his auto plant in Dearborn. The result was Greenfield Village, and it is a weird, uncanny place—a replica of a historic small American town, but set in no particular time or place.

Ford took the Wright Brothers’ workshop from its original location in Ohio and brought it to his village. He took what was left of Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park laboratory from New Jersey. He added a 1600s British cottage from the Cotswolds, and Noah Webster’s house from New Haven, Connecticut. He went around to antique stores across the country, amassing endless objects of miscellaneous Americana and arranging them in the village and its accompanying museum. Today, for a pricey entrance fee, one can visit this little slice of the past, where restored Model Ts buzz around and American history is presented as the history of innovations culminating in the wondrous Ford motor car. (Be careful about buying refreshments. A bag of freeze dried Skittles in the gift shop costs $15.)

The village is supposed to be educational, sort of. But it’s more like a tycoon’s giant train set. Ford disdained historians. “History is bunk,” he would often declare. Greenfield Village has been viewed skeptically by historians for its “lack of intellectual coherence.” But that’s the point. The village was not attempting to show history as it actually happened, but to create a kind of vision of a lost paradise, an America that Ford had warm nostalgic feelings for.

It was an America that Ford himself was destroying, and he knew it. His factories were killing the small craftsman, and his cheap, mass-produced cars would produce the nightmare of suburban sprawl (and, ultimately, the catastrophe of climate change). The building of Greenfield Village, Watts says, reflected “an underlying uneasiness with the industrial world that he had created.” The “central designer of the modern American industrial order was in love with the virtues of rural life.” Ford identified with agrarian and small town America. (“I want to see every acre of the earth’s surface covered with little farms, with happy, contented people living on them,” he said.) Greenfield Village was to offer “emotional satisfaction by providing a temporary escape from the intensity of modern life.” But Ford remained a “technofuturist,” publishing a work called Machinery, The New Messiah arguing that technological improvements could solve all of humanity’s problems.

Ford may have known on some level that the system he had created was dehumanizing, and that he had done more than anyone to turn workers into “cogs in a machine.” (His assembly line would soon be famously satirized by Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times.) But instead of reorganizing his production process to make it less despotic and hierarchical, instituting real workplace democracy, he built a giant toy village where Americans could go and look, as if into a snow globe, at an idealized tapestry of the country they had lost through the rise of industrial capitalism.

What lessons do we take from the story of Henry Ford? The most obvious should be the dangers of giving a single man a great deal of power and control.

There are obvious parallels between the lives of Henry Ford and Elon Musk. Both men amassed unfathomable riches in the automobile industry. Both men are megalomaniacs with a hatred for unions. Both went somewhat mad with power. Associates reported that Ford “began to get the feeling that he was infallible and his decisions were always right,” and “made this into such a personal corporation that he himself was the only source of authority in it.” He resisted “catering to the whims of buyers,” insisting on maintaining his beloved Model T long after it was outdated. Said one associate, “It was the old man’s belief that he knew best what was good for them [the public] and he was going to give them what was best.” Similarly, Musk insists on selling his idiosyncratic (to use the politest term possible) Cybertruck, even though it has flopped with the public.

Both men showed disdain for academic knowledge, and used their positions to spread crackpot right-wing political theories. Both neglected their companies in pursuit of ideological obsessions. Both built their own bizarre towns, with Musk creating a “Memes Street” in “Starbase, Texas.” As Harold Meyerson of the American Prospect writes, Musk has “joined Ford as the most prominent American employer of his era implacably opposed to unions” and “Ford’s vociferous antisemitism helped to fuel the rise of German Nazism, while Musk has now gone all in to promote the rise of Germany’s neo-Nazis.” Both men thought they were saving the world while continuously fucking it up.

Neither has been entirely a negative force. Visiting Greenfield Village and the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation is a fun day out, and Tesla helped to make zero-emissions vehicles more attractive to consumers. But both lives are cautionary tales about the concentration of power and wealth. Someone at the head of a vast industrial machine can easily take on a position like that of führer, and if they go mad, they can cause an awful lot of harm. Ford’s pushing of deranged antisemitic conspiracies encouraged American sympathy for the Nazis. Musk, similarly, pushes anti-trans, anti-immigrant conspiracies that are creating a more poisonous and dangerous political atmosphere, in addition to his direct work helping Donald Trump gut life-saving government programs.

The careers of both men show deep flaws in the American economic system. A boss shouldn’t be able to surveil workers at home. Success shouldn’t confer a giant megaphone that can be used to push fascist ideology. Henry Ford in many ways created America as we know it. We have to create an America that will not give rise to any more Henry Fords.