Why Fascists Always Come for the Socialists First

Contrary to right-wing myths that the "Nazis were socialist," fascists despise socialism and want to destroy it. Here's why the left poses such a threat to them.

Fascism is one of the most overused terms in any language, such that even socialists have started to weary of seeing it splayed on everything. In recent American history everyone from Barack Obama and Kamala Harris to Donald Trump and the MAGA movement have been called fascists. One of the most obscene iterations of this have been efforts by (mostly center-right) commentators to suggest that fascism was in fact a movement of the far left, or that fascists were even socialists. From Jonah Goldberg’s by now widely mocked Liberal Fascism, to Peter Hitchens calling the Nazis “left wing racists,” the genre is popularenough to have spawned numerous mocking responses.

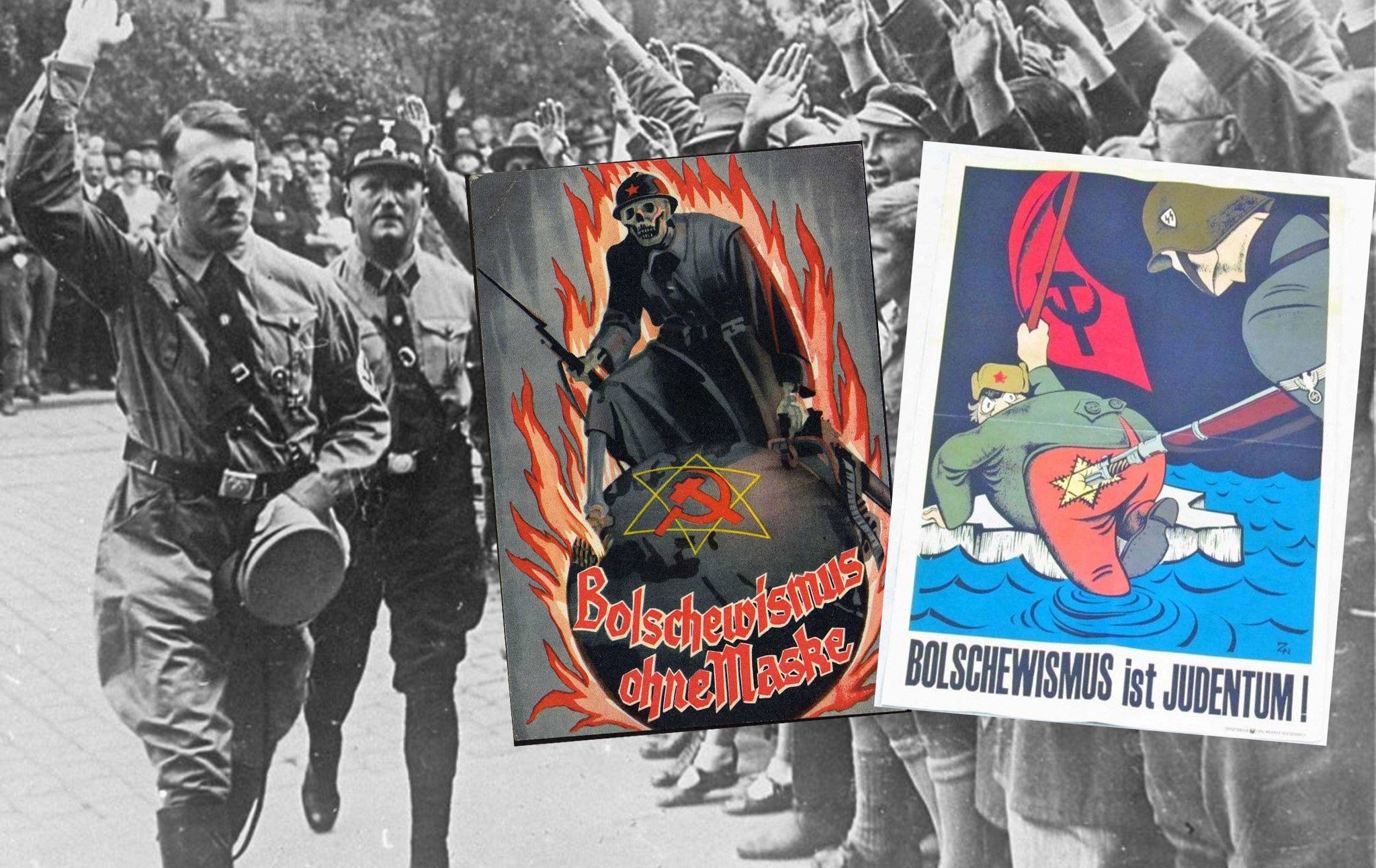

This talking point has been ruthlessly and effectively cut down in these pages and elsewhere, and looks ever more ridiculous as more and more young Republicans are revealed as overt admirers of fascism and Nazism. So I won’t reheat it here. Instead, I want to examine the inherent enmity between socialism and fascism, where it comes from, and why. Obviously, I don’t mean to suggest that socialists are the only, or even the primary victims of fascist evil: millions of queer, disabled, Jewish, Roma, and other groups were also brutally trampled by the fascist jackboot. Still, as Martin Niemöller’s famous poem goes, “First they came for the communists,” and if we want to understand and combat fascism today, it’s vital to know why that is.

Fascism and the Broader Right

The relationship between fascism and the broader right is complicated. In early 20th century Italy and Germany, it’s quite likely that many conservatives and capitalists would have preferred a more conventional conservative dictatorship that eschewed populist mass politics—all those disruptive rallies, parades, street fighting, and efforts to build a new kind of totalizing nationalist order. But this didn’t keep them for signing on to fascism when the red flag was marching.

In his 1927 book Liberalism, the ultra-pro-capitalist economist (and later Ayn Rand fan) Ludwig von Mises applauded “fascism and similar movements aiming at the establishment of dictatorships” for being “full of the best intentions” and “for the moment, [having] saved European civilization…” from Red takeover. Like many on the European right, Von Mises was horrified by the October Revolution that brought the Bolsheviks to power in Russia, the socialist revolutions in Germany that resulted in the largely Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD)-built Weimar Republic, and the rise of left-wing parties across the continent. In this respect he saw fascism as an emergency “break glass” necessity—an opinion shared by conservatives like Churchill, who called Mussolini “the greatest law-giver among living men,” for some time. Nevertheless, in Liberalism Von Mises expressed concern about authoritarian excess and recommended Mussolini and others hurry along in restoring or creating a free-market society. For him, as for others, fascism was somewhere between a useful emergency measure and a necessary evil. In Spain and Romania, conventional conservative dictators sometimes elevated homegrown fascist movements like the Falange and the Iron Guard to prop up their legitimacy—only to marginalize or crush them when they became a potential threat.

These qualified reservations didn’t prevent many on the broader right from cooperating with fascist takeovers where it was advantageous. In his recent Fascism: A Quick Immersion, Roger Griffin highlights how in the early days the exact ideological orientation of fascism was up for debate, Mussolini vacillated on which way to go, torn between his earlier socialist convictions and the movement’s burgeoning anti-communism and nationalism. After October 1922, when Mussolini became Prime Minister, Italian “Fascism mutated again, and Mussolini himself wore a bowler hat and a ‘bourgeois suit’” alongside a military uniform. This signified to supportive conservatives that the new regime was decidedly on their side. While in power, Italian Fascism “enjoyed the active collusion of the monarchy, the Catholic Church, and much of the industrial and rural bourgeoise, all deeply reactionary forces,” which helps account for “Fascism’s rapid shift to the extreme right and its subsequent new iteration as a totalitarian regime.” This conciliation was brought about in no small part because many on the right agreed with Von Mises that the Italian Fascists were, if a little rough, very good at suppressing the communists and socialists. (For the Church, in particular, anything was better than the existential threat posed by Marxism and its “godless” materialism.)

In The Coming of the Third Reich, Richard Evans notes how in Germany, conservatives in the army, big business and beyond collaborated to help the Nazis win office:

[The] conservatives who levered Hitler into power shared a good deal of [his] vision. They really did look back with nostalgia to the past, and yearn for the restoration of the Hohenzolleren monarchy and the Bismarkian Reich. But these were to be restored in a form purged of what they saw as unwise concessions that had been made to democracy. In their vision of the future, everyone was to know their place, and the working classes especially were to be kept where they belonged, out of the political-decision making process altogether.

In other words, they wanted to have it both ways: to keep all of the advances in military power and industrial productivity that modernity had brought, while rolling back the democratic changes in the structure of society that came with them.

In particular, Evans stresses that German conservatives and big business tolerated or cooperated with the Nazis expressly to prevent offering any concessions to the electorally powerful, but social-democratic SPD. Richard Paxton is even more emphatic in The Anatomy of Fascism when he points out the Nazi movement might have “ended as a footnote to history had it not been saved in the opening days of 1933 by conservative politicians who wanted to pilfer its following and use its political muscle for their own purposes.” This went so far that the more generically conservative party, the German National People’s party, formed a coalition with the NSDAP and supported their dictatorial ambitions.

Understanding this history of broader right-wing conciliation with fascism can help us grasp why many self-described conservatives today still cooperate with the far right to combat what they see as “leftist degeneracy.” Recently the Heritage Foundation has come under fire for providing cover for Tucker Carlson’s chat with Nick Fuentes, who is probably the most prominent neo-Nazi and Holocaust denier alive today. For those fortunate enough to not be in the know, Carlson has long been infamous for blowhorning white nationalism and platforming Nazi revisionist histories. But a friendly chat with Fuentes still shocked many (though it shouldn’t have). JD Vance, too, has blurbed a book that explicitly praises Spanish authoritarian General Francisco Franco, and he recently brushed off the revelation that many GOP staffers routinely invoke Nazi rhetoric by claiming they’re just “kids” (many of them 30 or older) who enjoy racy humor and triggering the libs. Many continue to express surprise that a once normal conservative movement seems so willing to conciliate and fanboy/girl with fascists. If they looked at the history, though, there are in fact few things less surprising. Fascists and conservatives have always been able to unite over their vehement loathing of the left. When one considers how the German right thought even the very liberal and democratic socialism of the SPD was a calamity, or how many contemporary far-right Republicans saw Joe Biden as the second coming of Stalin, it all makes sense.

What is Fascism?

Fascism would never have obtained meaningful power if it hadn’t been for support from the broader, more mainstream conservative right. But fascism is not just conservatism or capitalism on steroids. Nor can fascism be understood as just a counter-revolutionary or reactionary force defined by its negations. One of the longstanding weaknesses of left-wing analyses of the right has been a propensity to see them purely as reactionary. This implies that the left are the true agents of history, who propose and push for changes, which the right then attempts to slow down or stop.

Now, at points this is what many on the right will do. But right-wing doctrines are not defined purely by reactionary instincts. They are defined by definite assertions and beliefs of their own—most importantly, the conviction that people (and peoples) are fundamentally unequal, and the best society is one that reflects natural or ordained inequalities. To obey a real superior is a great social virtue, to paraphrase the conservative James Fitzjames Stephen. This anti-egalitarianism can assume a conservative form where those on the right seek to uphold existing hierarchical authorities they regard as, by and large, legitimate. But it can also assume revolutionary and even utopian forms, where the radical right will fantasize about restoring or creating utopian kinds of society where the true “organic” hierarchy will express itself. Oftentimes this is coded in restorationist language, as it was in self-described “super-fascist” Julius Evola’s Ride the Tiger:

Like the true state, the hierarchical, organic state has ceased to exist. No comparable party or movement exists, offering itself as a defender of higher ideas, to which one can unconditionally adhere and support with absolute fidelity. The present world of party politics consists only of the regime of petty politicians, who, whatever their party affiliations, are often figureheads at the service of financial, industrial or corporate interests. The situation has gone so far that even if parties or movements of a different type existed, they would have almost no following among the rootless masses who respond only to those who promise material advantages and “social conquests.”

But as Corey Robin notes in The Reactionary Mind, the very radicalness of far-right nostalgia means that someone like Evola is forced to admit it is the future, not the past, that is the horizon of their political fantasies. The present moment is perceived as so rotten and corrupted by liberalism, socialism, and democracy that there is functionally nothing left to conserve. Many fascists will even express hostility towards conservatives while feeling compelled to cooperate with them. Fascists often see conservatives as sclerotic, timid, and incapable of rolling back the tide of decadent forces that are overwhelming the national culture. In How to Read Hitler, Neil Gregor notes how Hitler became radicalized in cosmopolitan Vienna. He came to despise the Social Democrats, Jews, and Marxists who he regarded as a singular, corrupting force. But as Gregor points out, he did not just blame the left, but also the “stupidity and credulity” of the “forces of the ‘old right,’ the ‘upper ten thousand’ whose failure to solve ‘the social problem’ had made it possible for Marxism, and thus for the Jews, to spread their pernicious influence.”

For someone like Hitler, the old conservative right couldn’t get the job done, and had failed to expand the power of the German nation. Radical action is what was required to bring about a higher kind of national rejuvenation, and that is what fascists offer. Depending on the tactical moment this meant fascists would variably cooperate with or sneer at more conventional conservatives. Much of the populist and grifter sensibility that defines fascism, then and now, stems from this distinctly petit bourgeois desire to retrench authority while also rising to the top of the social hierarchy where fascists think they ought to be. When modern hard right figures like Fuentes talk about “cuckservatives” and “Con Inc”—mocking the GOP establishment while trying, with considerable success, to strongarm and replace them—it echoes this history.

The most widely accepted scholarly definition of “generic fascism” is Griffin’s. In his classic book The Nature of Fascism he defines fascism thus:

“Fascism is a genus of political ideology whose mythic core in its various permutations is a palingenetic form of populist ultranationalism.”

In other words, fascists project the existence of an “ultranation,” which rarely conforms to the actual boundaries and citizens of an existing nation-state. They insist that the ultranation is the total locus of meaning in people’s lives, and that it needs to be restored. The term “palingenesis” refers to rebirth or recreation. The ultranation is often given an organic quality, as in Evola’s work, conceived as a superorganism over and above the individuals who make it up. Oftentimes this organic connection is made by directly appealing to race and racist pseudo-science to define a “pure” blooded Aryan community that risks infection. In Mein Kampf Hitler made just these claims, describing the racial health of the nation as vital to the millennial restoration of Germany:

The racial state must make up for what everyone else today has neglected in this field. It must set race in the centre of all life. It must take care to keep it pure. It must declare the child to be the most precious treasure of the people. It must see to it that only the healthy beget children; but there is only one disgrace: despite one’s own sickness and deficiencies, to bring children into the world, and one highest honor: to renounce doing so. And conversely it must be considered reprehensible: to withhold healthy children from the nation. Here the state must act as the guardian of a millennial future in the face of which the wishes and selfishness of the individual must appear as nothing and submit.

But at its core the ultranation is a mythological idea, a secular faith (which isn’t to say forms of Christian and religious fascisms don’t exist, often combined with nationalist aggrandizement). Sometimes fascists even demonstrate an awareness that the idea of the ultranation is simply made up, but don’t care. What matters isn’t the reality of the ultranation, but the meaning it provides. As Mussolini put it in a 1922 speech:

We have created our myth. The myth is a faith, a passion. It is not necessary for it to be a reality. It is a reality in the sense that it is a stimulus, is hope, is faith, is courage. Our myth is the nation, our myth is the greatness of the nation! And it is to this myth, this greatness, which we want to translate into a total reality, that we subordinate everything else.

Usually fascists nostalgically and selectively rhapsodize about a time when the ultranation was strong, virile and powerful: the Roman empire, the Second German Reich under Bismark, or the heady days when the Hungarians defended Christendom from the barbarous Islamic Ottomans. (Or, for today’s American far-right, a rose-tinted pastiche of the 1950s created largely from advertisements.) But since then the ultranation has declined due to the nefarious influence of enemies within and out who bring about corruption, lethargy and decadence: socialism, communism, materialism, feminism, democracy, liberalism, the more consumeristic forms of capitalism, foreign invaders and immigrants, or all of the above. The fascist promises a revolutionary movement will restore the ultranation to glory. But only if the movement speaking for ordinary people is given near absolute control.

Fascists reject democracy but tend to embrace populism. The leader—almost always a preening, dramatic man—is pitched as a visionary figure embodying the true will of his people, meaning he must be allowed to act without constraint. Liberal or democratic checks on the fascist leader’s authority are perceived as neutering the will of the people and risks regressing politics back to boring, democratic and intellectual debate between competing factions. Once in control, the movement and leader promise to purge national enemies and make the ultranation great again. For many fascists this has meant mass, imperial expansion, undertaken as both as means of empowering the nation and as an end in itself. (Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 fell under this category.) Fascists view violence and the exercise of power as spiritually elevating, bringing the people out of decadent egoism and selfishness and sharpening the existential intensity of life.

Fascist Anti-Socialism

The Jewish doctrine of Marxism rejects the aristocratic principle of Nature and replaces the eternal privilege of power and strength by the mass of numbers and their dead weight. Thus it denies the value of personality in man, contests the significance of nationality and race, and thereby withdraws from humanity the premise of its existence and its culture. As a foundation of the universe, this doctrine would bring about the end of any order intellectually conceivable to man.

— Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf

Having defined fascism and described it in relation to the broader right, we’re now in a better position to understand the history of fascist anti-socialism. Fascists despise many things about socialism. In particular, and related, are its rationalism, materialism, cosmopolitan universalism, and above all socialism’s egalitarianism.

Fascists despise socialism’s rationalism and intellectualism, associating it with quashing the personality’s heroic aspirations. Part of this aligns fascism with a broader right-wing revulsion towards excessive reason and a celebration of what Roger Scruton, in The Meaning of Conservatism, applauded as “unthinking people.” By and large, the right doesn’t like individuals exercising their reason excessively, since that has a dangerous tendency of turning quiescent subjects into demanding citizens. Fascism differs from the broader right in accepting and sometimes even wanting the masses involved in politics, albeit subject to the populist authoritarian leader’s direction and control. But they still associate excess intellectualism, of the sort socialists have always endorsed as part of raising class consciousness and as vital to a well-run society, as dispiriting and confusing. In their view, it inoculates against the will to act. Fascist philosopher Giovanni Gentile made this point explicit in The Origins and Doctrine of Fascism when he disparaged how intellectualism “divorces thought from action, science from life, the brain from the heart, and theory from practice. It is the posture of the talker and the skeptic, of the person who entrenches himself behind the maxim that it is one thing to say something and another thing to do it; it is the utopian who is the fabricator of systems that will never face concrete reality[…]” It’s not just particular thoughts that fascism discourages, but the act of thinking itself.

More specifically, fascists regard socialists as little different than liberals in being fixated on rationalistic economic concerns, and consequently reducing humankind to an undifferentiated herd of cattle to be cared for by what white nationalist Sam Francis disparagingly called a “managerial” state that will bring about passivity. In “The Doctrine of Fascism” by Mussolini (much of it was actually ghostwritten by Gentile), fascism is described as the “resolute negation” of “so-called scientific and Marxian socialism” which describes history in terms of class struggle. Ideologically this is because fascists don’t share socialists’ optimistic view that with the end of class struggle will come the advent of a more rational society. Politically, as we’ve seen, fascists often drummed up support from big business in Italy and Germany by promising to end class struggle without the need to challenge capital’s ownership of the means of production.

Nationalism might bring an end to class struggle domestically, but then the ultranation must pursue new heroic projects elsewhere. This is because fascists deny that economic precarity is the basic social problem, and also that using reason to design a well-functioning economic system that secures the good things of life for all is a worthy aspiration. Mussolini (or rather Gentile speaking through Mussolini) insisted that the fascist “believes now and always in sanctity and heroism, that is to say in acts in which no economic motive — remote or immediate — is at work.”

Often fascists will conflate socialism and liberalism as twin bastard offspring of the Enlightenment in this commitment to metaphysical and spiritual materialism. In his Introduction to Metaphysics, Nazi philosopher Martin Heidegger proclaimed that the Soviet Union and the United States were “metaphysically the same.” Liberal capitalists and socialists agreed that the world consisted of matter in motion governed by scientific laws that could be understood and manipulated by human reason. The goal of life was consequently to harness the power of science and technology to gratify human desires. This point has been widely misunderstood by many socialist and liberal critics who project their own economic fixations into fascist ideology and praxis. By and large fascists thinkers and actors disdained this shared Enlightenment economism as reflective of a deeper materialist rot.

Fascists saw economics as a low (often Jewish) activity that should be subordinated to political and volkish/racial concerns. In Fascism: Comparison and Definition historian Stanley Payne emphasizes how Hitler had “no very precise ideas of political economy or structure, save that economics was not important in itself and must be subordinated to national political considerations.” Heidegger thought the same in more highfalutin terms. As far as he was concerned, the allegedly epic confrontation between capitalism and socialism was actually nothing more than a pathetic debate about how to efficiently build and best distribute refrigerators. By contrast the Nazi movement had grown out of the more spiritually attuned and heroic German volk, a kind of mystical collective spirit, and so was destined to smash both capitalism and socialism to bring about the grandiose redemption of the entire west. This fantasy attests to the acuity of Marxist critics like Theodor Adorno and Erich Fromm, who saw in fascism’s “jargon of authenticity” an effort to escape from reality and its chaos into a mythic fantasy world based on power and order.

The cosmopolitan universalism and aspirational pacifism of socialism is also an enormous source of antagonism. Socialists differ from (at least classical) liberals in largely accepting the inevitability of social conflict; namely class conflict. This meant that fascist philosophers like Carl Schmitt have sometimes expressed grudging preference for socialist’s realism over liberal squishiness. But from Marx onwards class conflict is usually understood to have a global dimension that is deeply affiliated with socialists’ belief that one day even this conflict will end. The workers of the world will unite because all of them, regardless of race or creed, are exploited by capitalism. In its less ambitious forms socialists may drop this historically dramatic vision while still holding onto a universalistic morality. We think that moral obligations are owed to everyone; therefore, a problematic feature of capitalism is its individualistic egoism.

Fascists despise this “rootless cosmopolitanism” and its adjacent belief that a world of peace and harmony between all is achievable once class exploitation is eliminated. In On Hitler’s Mein Kampf: The Poetics of National Socialism, Albrecht Koschorke explains that Hitler described his anti-socialism as emerging from a “hatred for—still more, [a] disgust with—social democrats, who ‘mislead’ or ‘seduce’ workers.” Hitler manipulated workers to reject the socialist idea of an international community united in struggle against global exploitation. Instead they were to conceive of themselves as a specifically German and Aryan Volk where class conflict would be eliminated internally, even if classes would still de facto exist. This is because all economic activity, even by private industry, would be steered toward the only goal worthy of a rejuvenated nation: the quest for lebensraum and empire through war. So Nazism would ensure class conflict would be internally eliminated (even if actual economic classes would still exist in Germany), and Hitler was certain that a violent global struggle between “races” was inevitable and desirable. It was set by the “aristocratic principle of nature” which held that the strong races must dominate the lesser, or untermensch.

This leads to the final point where fascists revile socialists: our commitment to equality. Socialists are instinctively and often reflexively egalitarian. We hold that (at least) all human life is equally sacred, meaning we have universal duties to any and all. This precludes us from prioritizing our individual or national desires to the point we ignore the needs of others or even prey upon them. Fascists completely reject this. Koschorke notes that from the “nationalist perspective—especially in the extremist, biologistic form that Hitler advocates—[one] sees a vertical principle of separation at work. Viewed in national terms, all members of the people are elated in essence. Inner division, then, amounts to a betrayal of their shared nature. By the same token, members of other peoples remain fundamentally alien.” For Fascists many human beings are not owed anything, and so can be used and abused as needed by the higher races. Or worse, many are regarded as simply “useless eaters” or “life unworthy of life,” either because of racial inferiority, ideological corruption, disability and more. The organic ultranation is weakened, even sickened by their presence, which justified the use of mass violence against them.

Many socialists struggle to really understand the appeal of the fascist worldview; they often reduce it to a bastardized reflection of economic interests, and little more. But its dimensions are fairly straightforward. Fascism offers a narrative of dispossession and victimization, projecting a paranoid worldview where sinister progressives were always trying to seize one’s duly earned property and national greatness. The logic is that, if it weren’t for the presence of these decadent forces, you, ordinary Germans or Italians, would be revered as the master race you are. The opposite is true, too: fascism offered and offers the ordinary men and women of the “ultranation” a sense of being a racial aristocrat. It gives them a taste of power and status, so long as they submit unquestioningly to the party and its leader. If you buy in, suddenly you’re not just an ordinary working stiff; you’re a part of the Great Heroic Aryan War Machine of Destiny, or maybe the Trump Train. For many people the left’s offer of equality will never be as seductive as the right’s offer of being a superior, especially when coupled with the resentment at being a victim dispossessed of aristocratic status by the unworthy. The fascist combination of elevation and resentful victimization can be intoxicating.

We can now see how, in many respects, fascism constitutes the exact inverse worldview to socialism. Socialists start from the view that all people are equal, regard national and individualistic chauvinism as contrary to our deep moral obligations, stress how we have more in common as finite, vulnerable human beings than what separates us, and want to use reason and science to build a better society for all. Fascists believe that people are fundamentally unequal from birth and become more so over time, insist that “higher” nations and races have special rights to preserve and strengthen themselves even at the expense of the weak, regard this as a reflection of the inner greatness that distinguishes them from lower forms of life, and reject humanism and rationalism in favor of a struggle for supremacy and domination. Their worldview thus licenses enormous violence against socialists and other “low” enemies.

The Banality of Evil

Fascism inflicted enormous suffering on the world before imploding in humiliating failure in the mid 20th century and then making an unwanted comeback. Much of this violence was directed at their socialist opponents, who—much to the concern of the broader right—seemed to be gaining ground everywhere post-World War I and during the Depression. The fascists were such effective anti-socialists and anti-leftists that their reputation on the right remained somewhat intact even after the Second World War.

Even in America, where there was never a significant fascist party that took power, related movements and sympathizers caused considerable damage in the 20th century and earlier. In The Anatomy of Fascism Paxton grimly notes that “the earlier phenomenon that can be functionally related to fascism is the Ku Klux Klan.” They adopted a uniform and used techniques of intimidation and violence to cow enemies of the white race, along with alleged communists and other Reds. In Fascism In America, Alex Reid Ross notes how Nazi sympathizing groups in the 1930s aimed to present themselves as white and patriotic while repudiating the Roosevelt Administration which “they identified with Jewish power and communism.” While ultimately unsuccessful given the country’s leftward swing in the 1930s, fascist sympathizers did contribute to an isolationist streak for much of the early part of the war.

This climaxed in the America First Committee’s (AFC) efforts to shift public opinion in German favor, or at least towards benign neutrality. Much like in Europe the AFC received considerable support from big business, which was increasingly looking for any ammunition it could aim at FDR and the New Deal. In their paper for Fascism in America, Matt Specter and Varsha Venkatasubramanian note how the AFC functioned as a “pressure group aimed at weakening the Democratic Party and discrediting President Roosevelt. Conservative anti-interventionists were afraid that American entry into the war would distract citizens from the limits of economic recovery and Roosevelt’s authoritarian handling of the Supreme Court.” After the war fascist anti-socialism and anti-communism continued to influence American affairs. America’s infamous “Operation Paperclip” brought Nazi scientists to the USA to help in the Cold War. This was in large part because of their scientific know-how. But of course it was also because they were understood to be militant and effective anti-communists who could be trusted to enthusiastically work against the Soviet Union.

But of course the real damage was caused in Europe, where overtly fascist movements took power and could execute their dictatorial vision. After 1919, the Italian Fascist party organized paramilitary squadristi or “black shirts” to serve as their muscle. The Italian Fascists promised to bring order to a fractiously class-riven Italy. During the “Red Years” this helped them gain considerable popularity as very effective militants against workers, socialists and communists. In Fascism: A Very Short Introduction Kevin Passmore describes how the Italian Fascists initially won the “support of many conservative small peasants and landless labourers, who agreed that the authorities were not protecting them from the left. Fascist squads (squadristi) began a violent campaign of intimidation against Catholics and especially Socialists, in which many hundreds were killed.” In Fascism: Comparison and Definition Stanley Payne describes the ideological appeal of fascism to the young especially. Against the “antinationalist Socialist revolution, it proposed an alternative revolution of a more authoritarian nationalist government, led by new elites and advancing broad new national interests.”

This was one of the reasons conservative and bourgeois elites were willing to lend Mussolini their support after his 1922 march on Rome. In power, the Italian Fascist party initially introduced many pro-capitalist measures. In her book The Capital Order, economist Clara Mattei notes how the Fascists were applauded by Italian and international capitalists for crushing the Socialist Party and Popular Party coalition which had become threateningly popular, winning 32 percent of parliamentary seats in 1919. Mussolini then implemented proto-austerity policies that rolled back economic rights through the 1920s before partially switching gears in the ’30s as a response to the Great Depression. Mussolini’s regime imprisoned thousands of dissidents, including iconic socialists like Gramsci and Carlo Rosselli, even before coming under Hitler’s orbit.

Most commentators today regard General Franco as a conservative authoritarian rather than an outright fascist. As a Catholic conservative, Franco was deeply wary of the populist dimensions of fascism, and like many European conservatives he was also wary of its utopian aspirations for the total rejuvenation of society. Nevertheless, Franco received immense help rising to power from the Axis powers, cooperated with the fascist Spanish Falange, and long contributed men and equipment to the Nazi cause throughout the Second World war. In Fascists Michael Mann estimates Nationalist killings at between 50,000-200,000, with hundreds of thousands more imprisoned and tortured. Many of Franco’s victims were Republicans, communists and socialists. Chillingly, Mann notes that when Heinrich Himmler visited Spain in 1940, he was “taken aback by the executions and overflowing prisons” and suggested reincorporating militants into the new order. Mann sneers that Himmler “did not seem to realize that working class militants were to Franco what Jews were to himself. Franco was to refuse Hitler’s and Himmler’s repeated requests to hand over Spanish Jews, but toward leftists he was merciless.”

But it was in Nazi Germany that anti-socialism and anti-communism were at their most vicious. From the beginning, Nazi paramilitary violence was heavily or even largely focused against socialists and communists. In Fascists Mann looked at 581 essays written for the Nazi party journal on “Why I became a Nazi.” The militants strongly emphasized a desire to combat enemies, and “Marxists/communists/socialists,” rather than Jews or any racial or religious group, “were seen as the main enemy in 63 percent of the essays.” As Mann put it, the “main enemies” of the Nazis had “become Bolsheviks, though often linked to Jews and ‘the system’ of Weimar.” The more things change the more they stay the same, and tin foil hat theories about insidious Marxist Jews and other minorities corrupting the nation remain very much with us.

This makes it unsurprising that part of the Nazis’ appeal to traditional conservative elites was a promise to exclude and eventually destroy the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and Communist Party (KPD) which had reliably won large numbers of votes. It helped that the SPD were the Nazis’ biggest electoral rivals, especially amongst the working class, and had largely founded the much-hated liberal democratic Weimar Republic. Uncoincidentally, the only votes cast against the Enabling Act came from the 94 SPD deputies in the Reichstag (the communist KPD was already effectively broken). In The Third Reich in Power, Evans notes that within months of the Nazis winning dictatorial power, there were already around 45,000 prisoners thrown into concentration camps and the “vast majority were Communists, Social Democrats and trade unionists.” Jane Caplan is even more grim in Nazi Germany: A Very Short Introduction. She notes how “Hitler’s elite collaborators had scripted him to solve their crisis of control by lending leadership and a popular mandate to an authoritarian government[…] Hitler fulfilled the first part of the bargain in the spring of 1933 with the Nazis’ crushing assault on the KPD and SPD (still hamstrung by mutual hostility) and on the trade unions; its speed and violence left their members in shocked disarray.”

After the war began persecution intensified, climaxing in Operation Barbarossa’s immense war to bring down the Soviet Union and with it the headquarters of so-called Jewish Bolshevism. Approximately 20 million Soviets died in the war—the largest death toll of any combatant nation. This included millions in the death camps alongside the Nazis’ countless other victims. The downward spiral was crushingly rendered in Niemöller’s iconic poem, which opens “First they came for the Communists”—an opening line that, as the Cold War kicked off in the 1950s, was often left out in American reprintings.

The sheer scale of fascism’s violence—its savagery and brutality—is haunting. But it's important to not go overboard in projecting a kind of demonic power and genius to fascists, who will go down in history as titanic failures. “Might makes right” is always the loser’s philosophy in the long run.

Self-described socialists have made many mistakes. Some of these have been brutally tragic and ruthlessly genocidal. Authoritarian socialists like Stalin committed mass atrocities that serve as a chilling reminder of the horrors that can be inflicted by those mouthing well meaning platitudes.. But the ethical core of socialism remains inspiring because, in sharp contrast to fascism, it makes far greater demands of us. Socialists want a world where, even if everyone won't be happy, ordinary human misery will replace unnecessary suffering. This is a goal that is so ethically demanding we’ve yet to fully build a society that realizes it. Despite all the bombast about heroism and power, in the end fascism resonates because it appeals to our lowest instincts. It is so tempting to imagine one’s self a dispossessed racial aristocrat, in part because that makes it so much easier to push aside all ethical demands that get in the way of our greed and lust for power. Fascists strive impotently for a bigness the shrunken aspirations of their soul can never reach. Fascism is the banal dream of tiny men and deserves its place in the sewage of history.