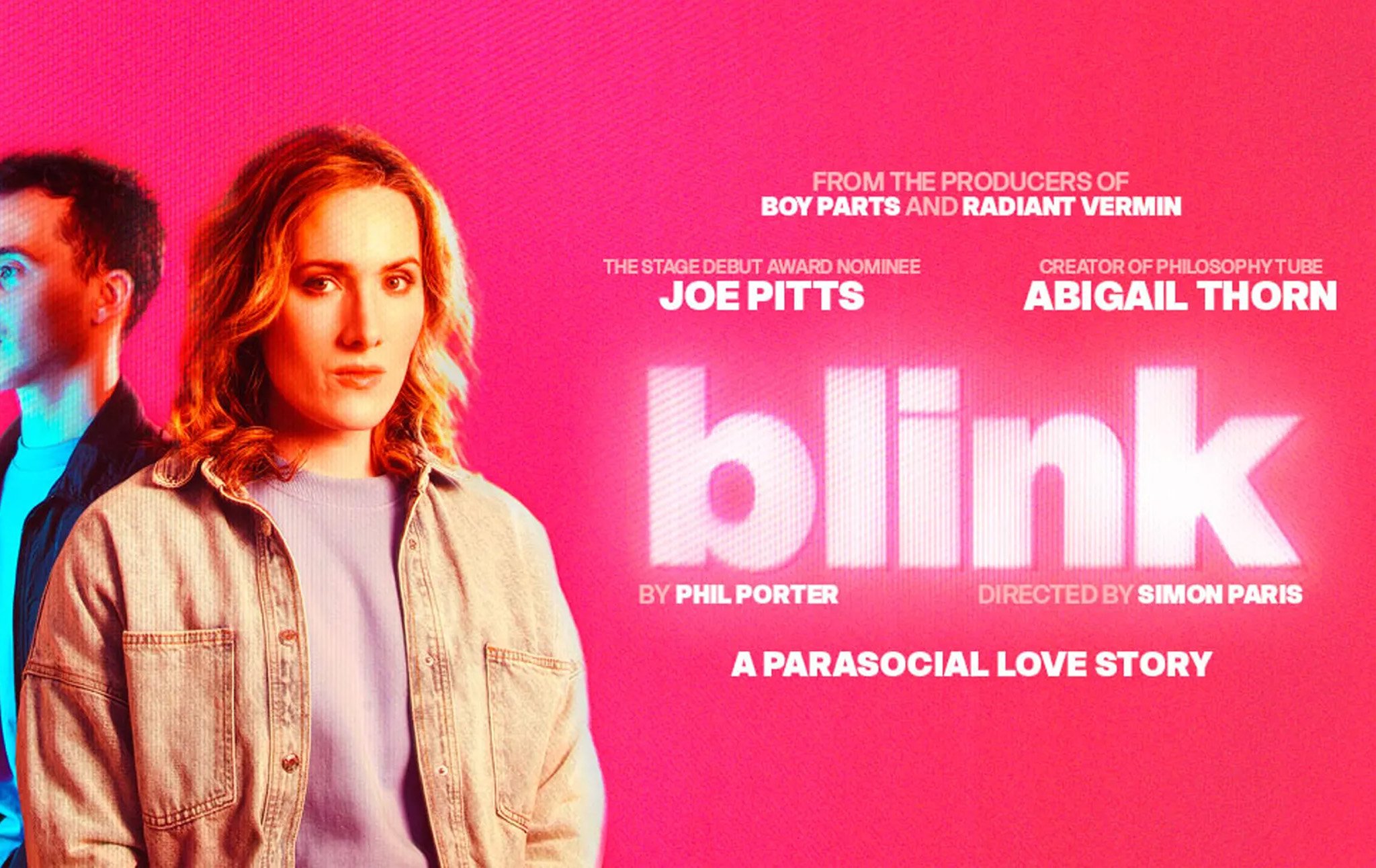

In her new production of “Blink,” the popular YouTuber explores the way digital media has radically changed human relationships.

Robinson

How do you feel about that dynamic between you and your viewers? Your channel now has a million and a half subscribers. These are people out in the world who come to you, and you speak to people like a friend. You’re helping guide them through the world of ideas. But of course, so many have never met you. How do you feel about this kind of dynamic between you and a million strangers?

Thorn

Well, it’s funny, because I’ve been doing Philosophy Tube for almost 13 years now, and it has grown at a pretty steady pace. There was never a moment where it really rocketed. I’m grateful, in fact, that it’s been pretty even, and therefore I’m kind of used to it. People come up and they say hello in the street, and it’s always very wonderful when they do that. The messages I like the most are when people say, “You’ve helped me understand my parent or my child,” or “I can speak to someone with a different point of view now because you’ve helped me understand.” Those are the moments that mean a lot to me. Or even just when people say, “Hey, I was going through a rough time, and your videos helped me”; those mean a lot to me.

I think what’s really an interesting difference between me and Sophie, the character I’m playing in this play, is that over the years, I have built up professional boundaries and had media training now through being an actor. I know what to say on camera and what sort of effect that will have, and I know where to draw the line between sharing a piece of myself and keeping my privacy. So, for instance, I never identify my family members. I never tell anyone which way I vote, and I never identify the people that I’m dating. Those are three core rules, and I have a number of other rules about the way I approach my work on Philosophy Tube emotionally. Sophie has none of that. She goes into it entirely naive. She shares way too much. She has no boundaries with this guy at all, and then interesting things result from that. And so I’m trying to get myself back into that mindset, like, okay, what was it like when I first started and had no concept of what was about to happen and no boundaries at all?

Robinson

You’ve had, as you say, quite positive experiences in this world that you’ve built up, and there are many people who really respect and like your work; it’s been very meaningful for them, helped them in their lives, and helped them learn things and work through ideas. But obviously, there are many dystopian aspects of the world that we live in now: the influencer economy, the world of parasocial relationships, content creation, loneliness, and the mediation of relationships through screens. Could you give us some thoughts on that?

Thorn

Well, certainly there are downsides. One of the professional boundaries I have is I try never to say anything negative about anyone publicly.

Robinson

Oh, I’m the opposite!

Thorn

Yes, well, I find that it helps, because Philosophy Tube is not just an educational show. It’s also an attitude towards learning. It’s about compassion and reason. So I try not to bash anybody, but I have certainly had some bad experiences, and I try not to draw attention to them. But there have been periods of backlash, and there have been things like stalkers. I’ve experienced that. The stalkers I’ve had who are bad tend to be people who are not the ones who hate you too much, but the ones who like you too much.

Robinson

Oh, really?

Thorn

Oh, yes. And this is not just something that YouTubers have to deal with. It’s something that a lot of women in the public eye have to deal with, and actors of all genders have to deal with as well. So it certainly does happen. I’d say one of the downsides of what I do for a living, both as an actor and as the creator of Philosophy Tube, is that it takes a lot of time. And so there is an alienation; there is a little bit of a loneliness to it. You have to love what you do if you want to be an actor or a content creator.

Robinson

I’ve been thinking recently about YouTube because our magazine has had to branch into doing more YouTube stuff because, obviously, print media is not really thriving at the moment. But YouTube is fascinating, isn’t it? Because in one way, it really has fulfilled its promise of democratizing the creation of content, and ordinary people who have things to say that are valuable can genuinely be successful on it. Now, your videos are known for pretty good production, but in the early days, you were doing things with just a camera and yourself, and you were able to succeed on it. On the other hand, it has a role in the spiraling of people into conspiracy theories and the alt-right. Do you have any thoughts on YouTube as a medium for the conveyance of information?

Thorn

Yes, that’s an interesting one. Because as my career has gone on, I’ve been interested in observing and charting what the fundamental limits of Philosophy Tube are as a project. And I don’t think all YouTube channels should necessarily be like mine. I set out with quite a clear and specific mission of what I wanted to achieve, and it’s been interesting to chart the shoals and the reefs of that. So one of the limits that I’ve encountered of Philosophy Tube as a project is that there are some people who do not want to learn, who want to remain ignorant, who do not want to hear different ideas and perspectives, and who even see the idea of critiquing something necessarily as an act of destruction, or rather, who see analysis as an act of destruction. And so one of the questions hanging over Philosophy Tube as a project is, well, what do we do with these people? And I don’t have an answer to that. It’s a question that I’ve shared with my audience. Another one of the limitations that we found only recently on the show is that by adapting philosophy and written words and articles and books into video, something is necessarily lost in translation, and something is also added, namely me and my personality and my perspective. And so there is no kind of perfect one-to-one relation between the in-person and the screen, which, again, going back to Blink, is kind of what the play is about.

Robinson

I was imagining if I were a snooty old academic Don who was very possessive of traditional philosophy and disdainful of this public project of making ideas accessible to everyone, I would say you dilute or cheapen ideas by bringing entertainment into it. But you believe strongly that performance, entertainment, and aesthetics actually have a role to play in getting people engaged and interested in serious ideas. Could you discuss your thoughts on that?

Thorn

Absolutely. Well, I think that Philosophy Tube could never be a substitute for getting an academic degree, and I’ve never claimed that it is. I’ve also never claimed to be a philosopher. Sometimes people say that I am, and I’m like, no, I never said I am and wouldn’t. But I think that not only can entertainment bring people into education, but also entertainment can be valuable for its own sake. And also, part of what Philosophy Tube as a project is for is sharing knowledge. So if I can share a reference to a famous novel, if I can share the plot of a play or a character that I’ve written that’s inspired by a famous work of art—if I can share that with someone, then why not?

I did a video a while ago on art and the meaning of artworks, and how philosophers talk about that. And part of what I was doing in that video was using the example of a Vladimir Nabokov novel called Pale Fire. And I thought, well, why shouldn’t my audience have opinions on great 20th-century literature? And the example I come back to is, if a mum in the Midwest is watching my content, why shouldn’t a mum in the Midwest have opinions about Shakespeare and Schopenhauer? And again, bringing it back to the play, I think one of the reasons I love doing this show, and one of the reasons that I was particularly attracted to taking this role, is that Blink is a play that, if you’ve never seen theater before or are a bit intimidated by theater, then, first of all, tickets start at 10 pounds. It’s not like the West End, where you pay 150 quid. And second of all, Blink is a very good first play to come and see, because you don’t need to have read all the Shakespeare and understand everything to get it. It’s just quite a simple story about two people in this strange situation. And so bringing these very highfalutin things back down to people who might not otherwise have access to them is, I guess, a common theme in Philosophy Tube and also sometimes in my acting career.

Robinson

As I was approaching this interview, I was thinking, what are the links between the work you’re doing right now in this play and the work you do on your channel? Finding novel routes to get people thinking or engaged in ideas seems to be something that is present both in this play and in your Philosophy Tube work. This play is telling a simple story of two people and has, as I understand, a fairly minimal cast. There aren’t many elements that are used to create this story. There are two people in two rooms, and yet, hopefully, the audience is going to go out and have a drink afterward and be discussing so many ideas that they could pull from seeing this story unfold.

Thorn

Absolutely. And it’s a very good time to do this show as well, because there’s this trend in London theater at the moment—this very hot trend not even in theater, but just in entertainment—where people will do storytelling slams, storytelling evenings where they’re not professional actors. You just get 10 people getting up to a microphone, and they each have five minutes, and they tell a true story from their life. And I, the director, and Joe Pitts, who plays Jonah in the show, went out to one of these storytelling evenings, and we were amazed. Obviously, being professional actors and a director, we’re used to this world of, okay, you have a set, you have characters, you have special effects, and so on. And actually, this evening, with just 10 people, non-professionals, telling their true stories for five minutes each with just a microphone and nothing else, it was A) sold out and B) absolutely electrifying. And so that’s kind of the hot trend in London theater at the moment. And so there are moments of direct address in Blink, where the characters speak directly to the audience and tell their story. We are really trying to capture that element of just basic storytelling, the storytelling where it’s just a caveman around a fire. Which I suppose, in a way, Philosophy Tube, as a show, sometimes has a lot of bells and whistles and fashion and characters and everything. Sometimes I deliberately strip it right back and try and go, okay, what’s the truth of just a woman in a room with a camera?

Robinson

Yes, and managing to make ideas, just an idea, interesting and engaging for half an hour or an hour—to take something simple and make it totally fascinating.

Thorn

Well, I think one of the videos I’m most proud of recently is one we did last year. I think it was called “Social Media vs. Democracy,” and the entire video is about 35 minutes long, and there are no cuts. It’s one continuous monologue that we did in one take, where I’m moving around and climbing through the set, just with a microphone, and there are no edits. I was like, okay, how do I strip this back so far that I’m not even editing it and it’s just the raw stuff? So it took a bit of practice, but the end result was very gratifying.

Robinson

May I ask you a little bit more about why you have gravitated towards the acting work? Because obviously you are someone who could, if you so chose, make a living doing YouTube videos entirely. So what is it that compels you so much that you return to the stage?

Thorn

Well, actually, funnily enough, I was an actor first. I’ve been acting since I was about five years old; I got my serious start doing Shakespeare as a teenager, and Tom Stoppard as well. I did Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. When I went to university, I always knew I wanted to go to drama school and be a professional actor. YouTube was a side project that kind of blew up before acting did. And so about five or six years ago, YouTube started really taking off, and then at the same time, I got cast in a comedy on the BBC, and then I did a Western for Sky and Netflix, and then it was Star Wars and House of the Dragon. Just bam, bam, bam, bam.

So these two things have really kind of come up. And what I did a few years ago with my first play that I wrote, The Prince, was I started putting them together and realized they could reinforce each other. Nebula, the streaming service that I co-own and that all my YouTube videos go on as well—you’ll see me talk about Nebula on YouTube; it’s the only brand I ever allowed to sponsor me—I got them to finance my play. We filmed the play, put it on Nebula, and it was a hit. So these two things are actually starting to go together.

I remember there was this amazing moment when I was doing Star Wars a couple of years ago, and we were lining up for the shot. I had a small role in the series, nothing major, and there were some quite big stars on set. So, on set with 100 people, I’m not the most important business; I’ll do my job, no problem. And we’re getting ready to line up, and I hear this voice go, “Abigail!” And this lady runs out from the video village, and she says, “Abigail, I’m Leslie Headland, the creator of the show. I just want to say my wife and I love your YouTube channel. Thank you so much for being here.” And I was like, oh my God. And I was looking over her shoulder at these A-list actors, being like, who’s this kind of jumped-up extra on our show? And so that was a really gratifying moment. It’s always really funny when the streams cross, even as I try to put them together deliberately. There was one incredible moment when we were doing Django, which was the Western I did. It was a night shoot, and we were standing on the side of this mountain in Romania, and it was a beautiful starry night. It was 1am, and I’m there in full 19th-century dress and a full Keira Knightley corset, standing with the director, and we’re just sort of looking at the stars. And he says, “By the way, I’ve watched some of your YouTube videos; my daughter is a big fan.” And I was like, I wasn’t expecting you to say that!

Robinson

You’ll never get away from it. It’s going to follow you forever.

Thorn

Oh, I don’t want to get away from it, though. That’s the lovely thing about it; it’s always nice when people know. It’s always just very strange. It’s a gear-change moment.

Robinson

Yes. Well, they’re two very different worlds. What I wanted to understand about what compels you about performance on stage is that, as I was thinking about it, these are such totally opposite things to do. When you’re doing philosophy, you’re thinking your own thoughts, taking it in whatever direction the ideas take you. When you’re acting, you are turning yourself over to somebody else’s writing and thoughts. Obviously, it’s very repetitive. You have to rehearse over and over, saying the same lines. It’s not spontaneous. So these are almost two kinds of—they’re not diametrically opposed activities, but they’re very different activities. So I want to understand better what is so compelling about being an actor.

Thorn

When I act—this is the only way I can explain it—it’s like I can use all of me. It’s not just my head; it’s my head and my heart and my body and my spirit, whatever that is. My voice, my creativity, my ability to research, to parse the text, which comes in very handy on Philosophy Tube, is also very useful for researching a role or diving into and analyzing a script. So there’s no part of me that I have to leave at home when I step onto a set or a stage or into a rehearsal room. It’s full and total, body and mind and soul creativity. And you say it’s not spontaneous, but I find acting, whether it’s on stage or on screen, often more spontaneous than Philosophy Tube, which is very cleverly rehearsed, and each intonation of each word is chosen to make it as clear as possible and to get the ideas across very clearly. Whereas, one of the things we’re working on, particularly with Blink, is not having an emotional plan for how the scene will go, just having an action that we’re playing and letting the emotions arise. So I think there is so much room for creativity, and acting is what I was made to do. I knew it from an early age.

Robinson

One of the things that I so appreciate about your work is you are combating what I think is a very dangerous tendency that has arisen as the right has resurged over the last decade. They have almost become better at the entertainment and performance side of it than our side. I think of Trump. Trump is a performer, and he’s, in some ways, a brilliant performer. He’s not a thinker. We come back with thoughts and fact checks and stats, and he gives them 90 minutes of just whatever it is he does at those rallies that keeps people’s eyes fixated. And you find a way, without sacrificing the depth of ideas, to bring the, lacking a better word, razzmatazz to our side.

Thorn

Oh, that’s sweet of you. Well, one of the things I do in Philosophy Tube is, I never try to tell people how to think, and I do know that people of all different political persuasions watch my show and enjoy it. I have my own perspectives and my own leanings, but I try never to push them on people. I do fail in that regard, and I like to try and fail in interesting ways. And so, yes, I guess it is nice. I never set out with philosophy to make it a political project. The thing about fascism is it’s kind of against thought, isn’t it? It is against reasoning. The nature of starting a channel where compassion, reason, thinking about things, reading, and truth matter and are important is you sort of inevitably end up on one side, really, and fortunately for me, it turned out to be the moral and correct one. So yes, I’m very flattered, though. You’re really glazing me by saying I’m bringing the razzmatazz to it.

Robinson

We don’t have aesthetics, but you do!

Thorn

Well, I’ve been around on YouTube long enough that I remember back in 2019-2020, people were talking about BreadTube and how BreadTube was going to deradicalize the alt-right. And I remember, at the time, being flattered by that but somewhat skeptical as well. I was like, well, I don’t think that consuming video content is really going to change—well, it can change people’s lives. It can do that. I know people who’ve come up to me and said, “This video really changed my perspective and my life in a way I didn’t anticipate.” But it’s not going to change the systems of power that are in place. Consuming content is not a substitute for material change, I suppose is what I’m trying to say, razzmatazz or not.

Robinson

Yes, that’s true. But as we know, I do think content has been very important for the right in terms of luring people in. You had some very vivid metaphor of a flower with a snake under it. They often look like debates. They look like ideas. There’s this performance of reasonableness, but underneath it is something very ugly. And I think that we do need to counter that part of it, the radicalizing process that occurs through their content.

Thorn

Well, first, “it looks like the flower, but with the serpent under it,” is Shakespeare. I can’t take credit for that. I think that’s a line from Macbeth. But yes, it sounds so trite to say that empathy can help people. It sounds so trite to say that seeing a person from somewhere else and understanding that they are a human being, seeing someone else’s perspective and understanding that they are just human, can help. Perhaps it can. Again, I don’t think it’s a substitute for material change, though. I think it’s an area reasonable people could disagree on. But bringing it back to the show, one of the things that I hope audiences take from Blink is that both Sophie and Jonah, the two characters in the show—I’m not going to spoil it—do some things that are maybe not 100 percent ethical. And I hope that people will come to understand—certainly, what the characters are trying to do in the play is make the audience understand—how they ended up in this situation. So if performance, razzmatazz, and empathy can help, that would be nice, and if they can’t, well, then I hope it’s at least a good night out.

Robinson

I would agree with you that it’s not a substitute for material change, but I would almost say that a precondition is to understand and care about other people and realize that even flawed people who do bad things deserve a level of compassion and care.

Thorn

Yes. Well, I think it was Bertolt Brecht who said that theater can be for the working class, but it also has to be a good night out. And he didn’t think those two things were necessarily opposed. He was an explicit Marxist and was using his theater for Marxist ends and was like, “And it also has to be fun.”

Robinson

Well, that is a good note to wrap up on, because we could say that Blink is both for the working class and a good night out.

Thorn

I hope so.

Robinson

So when does it open? And how can people come see it?

Thorn

We open on the 19th of February. We run until the 22nd of March at the King’s Head Theatre in London. And I can also tell you if you use the code “front row” as you buy your tickets, then you can unlock the first two rows. And this is a show where I think you’re going to want to be sitting in the front two rows.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.