How We Reached Carmageddon

Cars are deadly, inefficient, and climate-killing. Cars aren't inevitable, and they are standing in the way of a better, transit-friendly future for our country.

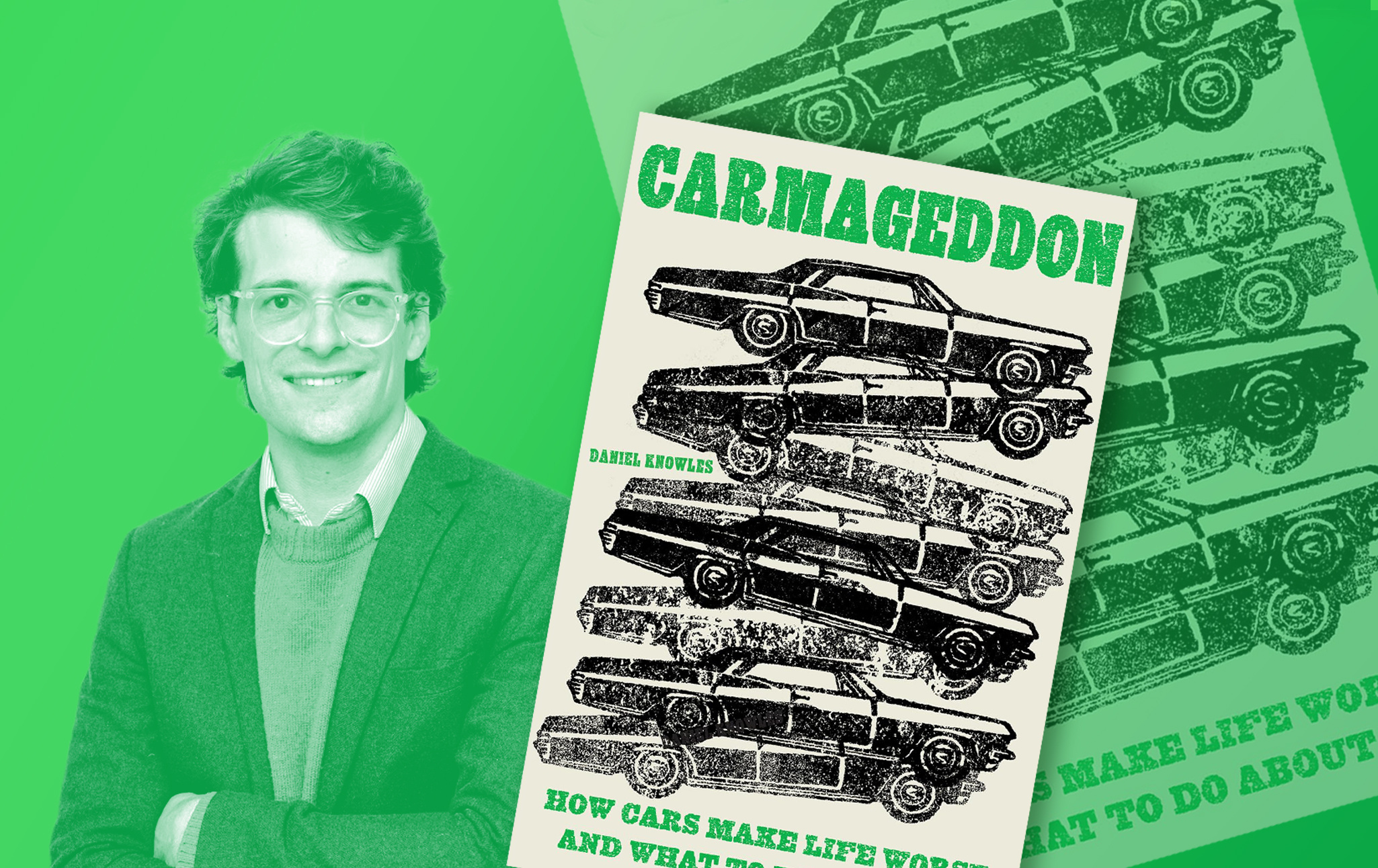

Daniel Knowles is a reporter for The Economist (yes, that one). In his book Carmageddon: How Cars Make Life Worse and What to do About It, he argues that cars are a problem and shows how we could have more satisfying, sustainable, and affordable lives with fewer cars. That's a tough sell in a car-loving country like the U.S.A., where we love our giant-ass trucks and our drive-thru daiquiri stands. Daniel is British: who is he to tell us we have to trade in our pedestrian-mashing SUVs for Chairman Mao-style bicycles?

Daniel explains all the ways that cars cause problems, why the situation we're in wasn't inevitable, and how we can change our deadly, inefficient, climate-killing ways and have transit that better serves human needs.

Nathan J. Robinson

Your book is a case against cars, car culture, and car-based infrastructure. Pretend I’m a person driving one of these colossal child-mashing trucks that have become so ubiquitous in this country in recent years. We’re talking, and you tell me about this new book of yours against cars. And I say to you, “Against cars?!” We're in a place where cars and roads are the water that we swim in. So where do you begin the critique when cars are so central to the culture and to how we get around?

Daniel Knowles

I've generally found that people are quite receptive—maybe not necessarily the guy who owns an F-150 and thinks it's the most important thing about his identity. But a lot of people recognize how much money they're spending on running a car and how much time they're spending in traffic, and they're frustrated by it and would like alternatives. In parts of the country where there really are no other options than driving—I was talking to a guy from Kansas a while ago about exactly this—sometimes people really struggle to imagine not having a car. They basically think, well, if I didn't have my car, the world would look exactly the same, and I'll just have to walk 10 miles to get anywhere. What I try to do—I don't always succeed—is to explain that it's not necessary. Everything is built in a particular way that makes the car necessary, and things can be built differently, and things can change. I’ve found people who listen to that. And the message is out there, not only from me but from many people, perhaps because cars have gotten so much more expensive in the last few years. There's certainly a hope. Do we really need all of this dependence on vehicles?

Robinson

It sounds like the first thing you're doing is to question people's assumption that there is no alternative to the role of cars in our lives right now. I wrote an article a couple of years ago called “Cars Are Weird.” The basic purpose of it was to say, just think about the fact that when you're driving a car, it's almost like you're bringing a big living room with you wherever you go. It's a huge, heavy thing used to transport you, a person, from one place to another. It's a massive amount of metal to have to move anywhere you go. I was trying to get people to think, isn't this a little strange that we do this and see this as normal?

Knowles

I'm going to have to look up that piece because I feel the same. What often really gets me is parking. When you are in some small town or somewhere that's very car dependent and go to a restaurant, the restaurant occupies one chunk of land, and then the parking lot around it occupies three or four times that. You think, why is so much space handed over to this means of transportation? It is strange. And people almost mentally cease to see cars; they block them out. We just filter them out of our eyesight and don't think about them because we grow up in this very car-centric world. Actually, the speeches I've given promoting this book are about how basically I went mad because I started seeing cars. It became an obsession, and I ended up writing a book.

Actually, one of the most interesting speeches I gave was at an elderly peoples’ home in the South Side of Chicago, and I'd say that the average age there was probably about 85. I gave this opening, and people were like, we see them all the time, and we hate them. It was a generation of people who were just about old enough to remember the world, in the United States, before everybody had a car all the time. They were telling all these stories about taking the streetcars to school as children and that sort of thing. And I guess they were in Hyde Park, and they said they remember the neighbors leaving the neighborhood, and they were the ones who stayed, so perhaps there's a sort of bias there, but I think it is a generational thing. Many of us have grown up surrounded by cars, so it can be very hard to think of anything else.

Robinson

But when you start to see it, and you end up in one of those colossal parking lots outside the mall, you start seeing this bleak, treeless, lifeless space. You think, my God, the waste, the waste! Is this the way that we have to get around? You write for The Economist, and one of the great and important concepts of economics is opportunity cost: what do you give up by having something else? I went out to Arizona to interview Noam Chomsky a couple of years ago, and I went to see one of his classes. I rode with him in his car and was in the back seat, and he had to spend ages looking for parking. This great mind, Noam Chomsky, just like everyone else, is hunting for parking. What thoughts could this mind have thought if he hadn’t been thinking about parking? What have we lost by becoming so dependent on cars?

Knowles

Primarily, we lose the ability to get around easily in any other way. Cars lead everything to be so spread out, and we need parking, so any given business occupies a large amount of space. There are all these cars going fast, which means that you might get hit by one. It means that if you want public transport that's effective, there are fewer people using it, which means it's less financially sustainable. Everything is so spread out, the density that supports a train network doesn't work as well because walking or getting to the station is just that much farther away. The main thing is that cars make other forms of transport harder.

We could build a lot more housing in cities that are very car dependent. If you're looking at, for example, Los Angeles, that's a key problem. Los Angeles is massive. It sprawls over so much land, yet the amount of living space that people who live there have on average is one of the smallest in the country, and it has more overcrowding than anywhere else in the country—in terms of actual in-your-house living space—because so much of the land is occupied by roads, parking, and low-rise living that fits between them. And if we weren't so dependent on cars, we could fit more people into those cities, whether it's Los Angeles or New York City.

New York City is very dense at its core, but actually, once you get out of Manhattan or the edges of Brooklyn or Queens, which are more populated, there are large areas of New York City, and certainly of the New York metropolitan area, that are very sprawling and difficult to get around in. And so, more people will be able to benefit from those higher-paying jobs that are generated in those cities if they can live in them. And then there's just the almost indirect opportunity cost of what we spend our money on. The poorest Americans—I think it's 20 percent of Americans—spend something like a quarter of their income on transport, and almost all of that is on cars. The median American family has two cars, and the average car costs something like $11,000 a year to run. So, these are really big sums of money that I imagine people would like to spend on things other than just getting around.

Robinson

Here in New Orleans, I spend $100 every year on transit. I live in the French Quarter, and I have a bicycle, and once a year, I take it to the bike shop. Sometimes the bike gets stolen, but that's about it. I've been out to Los Angeles, and every time I go out there, I think, I could not live here. Some people might have a tolerance for spending hours sitting in traffic. But I went to visit a friend of mine there. And every day, when he got home from work, the first thing he had to do was hunt around for parking in his neighborhood for half an hour before he could even go into his house, sit down, and relax. What a hit to the quality of life—the amount of hours in your day that you must spend on all the unpredictable stuff like traffic on the freeway. I couldn't believe that anyone endured this. I have to live someplace where I'm not going to sit in traffic. Otherwise, I will go crazy.

Knowles

Right. It just drives people mad. There's a study I cite in the book that shows that driving is by far the least popular way to get around. Even what is often considered a really grubby, miserable way to travel—the city bus—per minute of travel is much more preferred. You can look at your phone, and you don't have to stress about hitting somebody. The main reason why so many people drive is that we choose to drive. Sometimes this is presented like it's a consumer choice, but we do it because the alternatives are so much worse in terms of how long it takes to get anywhere and how reliable they are. Those alternatives are generally worse precisely because there are so many drivers. It's a catch-22. You have to drive because everything else sucks because you have to drive or because everybody's driving.

Robinson

Well, let me just put the counterargument to you, which I once heard made by Elon Musk: cars are freedom, and nobody likes public transit because it’s full of strangers who might kill you. That was the less serious point, but the more serious point he made was that it doesn't take you where you need to go. A car is always going to be more specific in that you don't have to wait for it. It will always get you to exactly the place that you are trying to get to, even though you're going to have to find parking there. Is it possible to really create an experience that is superior to that?

Knowles

He's not wrong, insofar as you're talking about an individual. The problem is that it's individuals versus everybody. If you're the only person with a car, it's by far the best. I pinched this from somebody else, but the only difference between me and the average American is that I hate all cars, and the average American hates all cars other than their own. Elon Musk has also talked about how awful and soul-destroying traffic jams are, which is why he has this plan to build these tunnels. And it's true: getting from A to B directly without having to wait at a bus stop in the rain or whatever is obviously more comfortable. It's just that when everything spreads out, it becomes inconvenient. And again, I think that's the coordination problem. Once some other people start getting cars, and everything begins to be built around cars, you have to get a car yourself.

The history part of my book really goes through this. If you look at the early parts of the automobile revolution, really rich people were getting cars and thinking, this is great, and then everybody else had to get cars as they shifted and changed the world to fit their automotive dreams. That happened everywhere, and I think that's really tricky to undo. It's a collective action problem: you have a car, great; everybody has a car, bad. I do think what’s happening with bicycles, and particularly with e-bikes, is that it’s beginning to provide an alternative that's a lot easier and that you can do individually.

Robinson

As you've pointed out, much of it depends on where you are. For me, riding a bicycle is much better at getting you from place to place; it takes twice as long to get there in a car because you sit in traffic, and you have to obey all the traffic lights. But when I'm in Florida visiting my parents, I have to drive because if you take a bicycle, you're on these 50 mile-an-hour roads in the suburbs, and people are going to kill you. If you go to Target and want to get across the street to CVS, you can't cross the street. You have to walk for about a mile to get to a traffic light, and at that traffic light there are cars speeding around the corner. You're taking your life in your hands, and I think, I'm not going to risk my life for toothpaste. I'm not going to stake my life on the principle that I want to walk to a place that's very nearby—even though I would much prefer to walk to a place nearby.

Knowles

Right. I'm quite militant, in general, about not using a car when I don't need to. And yet, last week I drove the rental car I had about 300 yards from the motel I was staying to a Walmart on the other side of the road because it was this huge highway with multiple lanes and things coming into it. I thought, I will die—it's late at night, people won't see me—if I try to cross this road. And I think that's exactly the problem. Even in places like Florida or even in this country, which is a very rich country where a large majority of people can afford a car—I'm not saying they want to, but they can—there's a proportion of people who can't afford a car, or they can but can't drive it for some other reason or because they don’t want to. God, the drunk driving that happens here—drunk driving is obviously an appalling thing to do, but people want to drink and be able to get home. You need alternatives, and taxis are expensive. That's a lot of labor. Even motorists and most people who drive don't actually want to have to drive all the time, everywhere. But because we've created a world in which the default assumption is that you will drive everywhere most of the time, it's impossible to get anywhere any other way. And I'm not saying to ban cars or stop them entirely, but if we all were able to drive less, our built environment could change in a way that suddenly would make it a lot easier for us to drive less. But just doing one without the other is tricky.

Robinson

You mentioned the fact that at one time early on, cars were the playthings of the rich, and you take us in the book back to the early days of cars. It's so important to be able to imagine different kinds of worlds, and you take us back to that point when the street was not for driving in but for doing everything in. The street was like the living room of the city. And when cars came along, they were annoying to the people in the street because they were disrupting the life of the street. It is a choice to give the street over to these obnoxious, deadly machines.

Knowles

The streets were for the people. In the context of the U.K., you can still find the generation of people who talk about playing in the streets in the 1950s and 1960s and how quickly that disappeared. That wasn't just automatic. The invention of jaywalking is one big example. Laws had to be passed so that you couldn’t just walk into the street because that's what people did, and it was very politically fraught. There was a lobbying operation led by car dealers and wealthier car owners to get stuff out of the way. Of course, they wanted that because when you are driving a car that can do 50 or 60 miles an hour, having to go slowly is the most incredibly frustrating thing. George Orwell wrote in the ’40s about our unwillingness to accept that we were putting the motorists above the lives of people who get run over.

To sum all that up, it didn't just happen like with iPhones, where this thing was invented, it became affordable, and everyone got one. To get everybody to have one required a whole bunch of political choices about how we use space, and principally street space, that took 20 to 30 years to happen. It was a political project, and it happened differently in different places. But it can be undone, too.

Robinson

I was in the U.K. a few months ago—my family's from there—and I went from my aunt's house in a village outside London to my grandmother's house in Solihull via train. I walked 10 minutes to the train station with my suitcases, got on the train, sat on the train eating a sandwich and perusing the internet, and several hours later, I got off the train and then walked 20 minutes down the street to my grandmother's house. It struck me when I got back here that this is impossible in the United States. I can't do this. I live in Louisiana, and if I want to go visit someone in Baton Rouge, I can't do it. But there's no reason why that should be the case. And I thought, another world is, in fact, possible. I have seen it.

Knowles

It's possible in the United States, almost, if you look at the Northeast Corridor—there is only really one part of this country where mainline train service is a thing. Amtrak makes a huge profit on that line even though by international standards it's quite low capacity and quite slow. It takes hours to get from D.C. to New York, which is around 200 miles. Even in the U.K., where we don't have particularly fast trains, that's quite slow, but those tickets sell out, and those trains are full. They are charging hundreds of dollars a ticket because it's far more comfortable than driving and sitting on the New Jersey tollway. It's easier than flying and probably door to door a lot quicker, too. The cheaper alternative is the bus.

So, people want to take those trains, and again, it would be quite easy to make a whole bunch of improvements on that line. With the right investment, it would speed it up and increase the number of trains you could run on it. People would pay for that because they already do. So, it's possible here. It's trickier in places where there is no infrastructure already. There is a lot of low-hanging fruit in this country—there isn't elsewhere—to change things relatively suddenly. It would allow people to get out of their cars before you even have to have the giant fight.

Robinson

It can feel so hopeless if you're in a place like Texas with some multi-lane freeway. You just look at it and think, how could this ever be undone? There are a couple other negative aspects of cars that we haven't gotten into. I don't think we touched on deaths, on cars killing people, and I don't think we touched on climate, both of which are quite important.

Knowles

It tells you how much we evidently think alike that we went straight to the urban planning aspects. Over a million people die each year worldwide, almost all of which are in poorer countries, except for over 40,000 a year in the United States. Even though they haven't banished the car, most rich countries have in the last 20 or 30 years really radically reduced the number of deaths caused by car crashes by mostly redesigning roads. They force drivers to go slower, particularly in places where they might hit another car or a pedestrian, and in the United States that hasn't really happened, at least not on a national level. There are places that have become a lot safer—New York City, for example. But so much of the population growth in this country has been in places like Florida or Texas, where people are forced to walk across these multi-lane highways, and often they get hit.

Drivers are basically encouraged by the road design to go very fast. I think car crashes are often treated like they're this inevitable accident, this thing that we just have to cope with as a cost of being able to get around. They're not. They're not inevitable. We actually tolerate them because we don't like having to slow down or concentrate. Americans find driving relaxing because it's quite easy. But when it's easy, when you're relaxed, that's when you make mistakes and bad things happen. Car crashes worldwide kill more people than HIV/AIDS does now, and quite possibly at some point will take over malaria. So, they will be more deadly than the deadliest communicable diseases.

Climate change is similar in that all the costs are concentrated in the developing world. But right now, there are something like a billion cars in the world, one for every seven or eight people. If everybody in India or China were to drive at the same rate as people in the West, there’d be no chance that even electrification would be able to save us from climate catastrophe. There's just so many people who don't drive at all at the moment, and they need mobility, but we can't just replicate what we've been doing for 100 years in the West everywhere else. We don't have the natural resources, and the climate can't take it. And unfortunately, in a lot of these cities, they are building freeways and sprawl because it's led by the upper middle class who can afford cars, in the same way it was here 100 years ago or in Europe 70 years ago. Those are the things that make me pessimistic. This is a global issue.

Robinson

How do we escape this trap? You mentioned low-hanging fruit.

Knowles

There's a huge amount of low-hanging fruit, and you can see places that are making incredible progress in things that do seem modest but that add up. One of the things that's happened so quickly in recent years in the U.S. is the abolishment of parking minimums, which require developers to make businesses provide a certain amount of parking—essentially, an amount of parking that's so large that you will never run out of parking spaces. That's really completely reshaped how most cities in this country look, and they've gotten rid of them.

Minneapolis is an interesting example. They built loads and loads of housing since getting rid of these requirements downtown, and now there are towers that you can live in. If you work in an office downtown, you'll probably be able to walk to work in 10 minutes. The city built a network of bike paths as well. So, if Minneapolis can do it, then many other places can, too.

In some European cities, and even New York City, you can see the amount that people drive is declining. In Paris, it's dropped by something like 40-50 percent. So, the boat can be turned around, and that's without huge, particularly drastic action. It's only really recently I'd say that this has become a political issue and a widespread, talked about thing. A lot of these improvements happened because individual bureaucrats and planners said, maybe we should change this thing. So, I only see those kinds of things accelerating in the next few years. Now, is it as fast as I would like? No. Is it as fast as is probably necessary to stop climate change? No. But it is happening, and the important thing is to push those things to move faster.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.