John Sanbonmatsu Thinks You’re Lying to Yourself About Food

The author of “The Omnivore’s Deception” argues that meat-eating is a “radical evil” that can’t be justified.

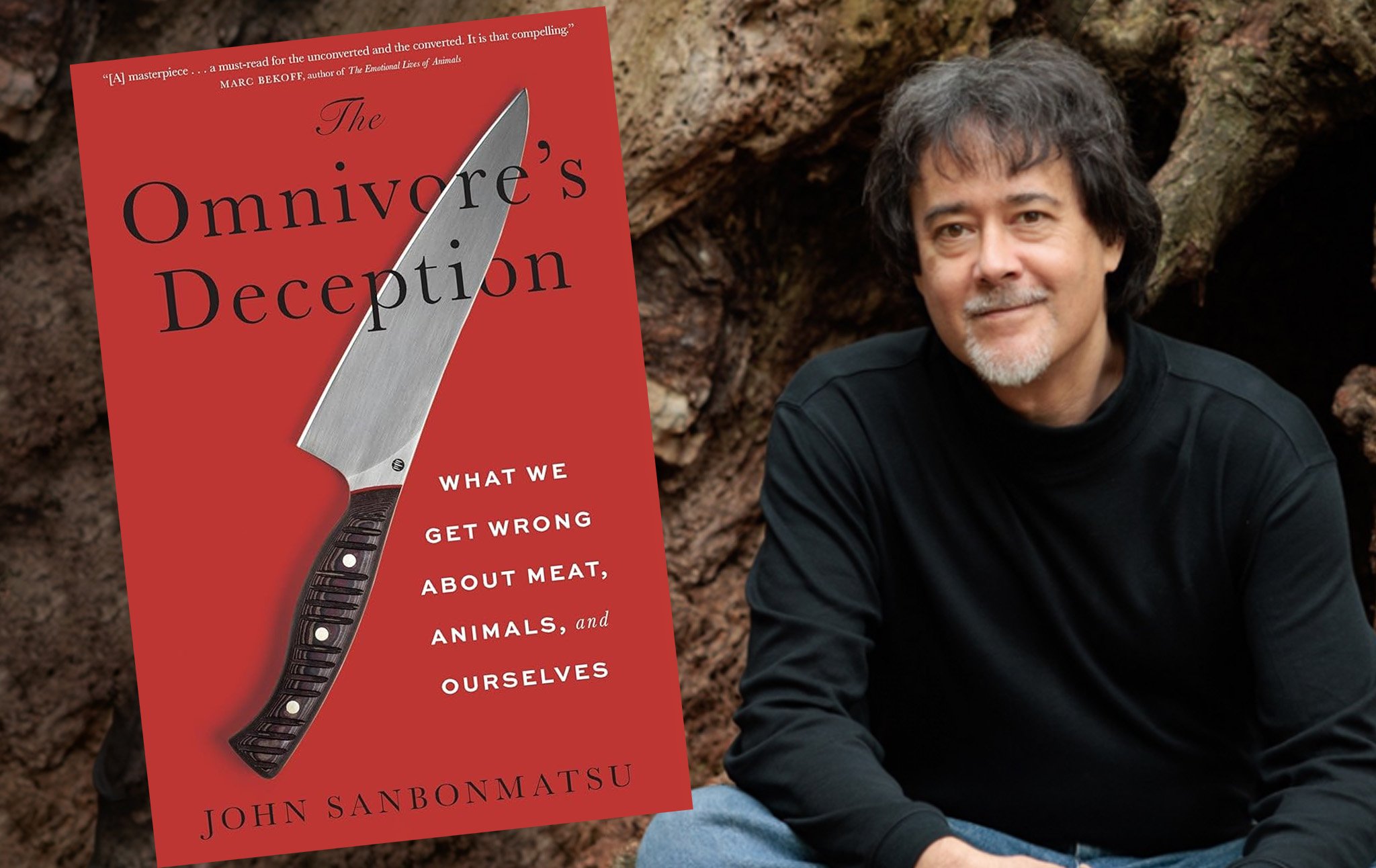

John sanbonmatsu is a professor of philosophy at Worcester Polytechnic Institute and the author of The Omnivore’s Deception: What We Get Wrong about Meat, Animals, and Ourselves. The book is a response to Michael Pollan’s 2006 bestseller The Omnivore’s Dilemma, and as the title suggests, Sanbonmatsu thinks writers like Pollan are dead wrong about the ethics of food. He maintains that killing and eating animals is entirely indefensible, no matter how “humane” the process supposedly is. He joined Current Affairs editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson to explain why.

Nathan J. Robinson

People might recognize your name if they’re regular readers of Current Affairs, because you appeared in one of the most recent issues of our print magazine, our special Animals Edition. Regular readers will know that we often cover animal rights and welfare, but we actually put together an entire special issue, which everyone should check out.

We had, in that issue, 15 Q&As with people who approach animal welfare from many different angles, from people who do direct action—people who have liberated mink from fur farms or rammed whaling ships—to people who are lawyers, and to you, John, the author of this powerful work of philosophy arguing about the deep immorality and need to confront head-on the full horror of the way that we treat animals. I think what you’re doing in here is so necessary but so difficult for people, because you are confronting many people’s deepest intuitions and their excuses, and you’re telling them, “No, actually, I’m sorry, but your excuses won’t fly.” Let’s start here with where you start in the book. You start with a quote in your introduction:“I tried vegetarianism once, not for the animals, for the environment.” Why did you choose that particular quote—something you’ve heard from people—to begin your story with?

John Sanbonmatsu

Well, we often hear questions of animal rights or the meat economy reduced to “sustainability” discourse, which is already the wrong starting point for what I describe in the book as a radical evil. And I literally have heard people say this for years, where people say, “Well, I tried vegetarianism once for environmental reasons.” And in fact, in the last five years or so, the press has been gleeful over the fact that many former vegetarians have been supposedly giving up their commitment to that now that they can have so-called “clean” meat, or animal products from supposedly sustainable sources. Now, that itself is simply a lie. There’s no way to provide a billion human beings with animal products without destroying the means of life on this planet. But no one wants to confront the fundamental issue, in my view, which is, first, a relation of domination. We see ourselves as the superior being who has a right, really a political right, to subordinate, exploit, and kill every other species. And secondly, and relatedly, the mass violence that is the underpinning of the thing. People who are otherwise nice, decent people are on board with a system of essentially universal genocide. Now that’s an analogy. We don’t have a word for what we do to nonhuman animals, but that is basically what we’re doing.

Robinson

But it’s peculiar, though, isn’t it? You’ve made a very strong charge there, that the ordinary, average person is on board with an indefensible system of mass killing that is a gross act of immorality, by which you mean our treatment of nonhuman animals. But it would also be the case that most people wouldn’t say that they oppose animal rights. They feel fondly towards the animals in their lives. They want, as you kind of hint there, a way to have their ethics and their meat at the same time. So tell us a little bit more about the contradictions, the cognitive dissonance in the way that people think about our relationships with animals.

Sanbonmatsu

I’ve been teaching ethics for 25 years, and I’ve thought a lot about this question of what it means to be an ethical person and also been very attentive, since I teach undergraduates, to the kind of contradictions that we live with. And I can’t think, honestly, of another domain of moral life where we would accept opposite forms of behavior in our relations with others as of equally valid import. And in the book, I give the example of shoving an elderly person down the stairs—we wouldn’t say that’s no better or worse than caring for an elderly parent, or child abuse being the same thing as raising a child in a loving way. And yet, if you open any newspaper, you’re going to find these opposite behaviors profiled in terms of our relations with other animals. There will be articles about cats and dogs and the sacrifices people make for their companion animals, and then there’ll be a recipe for pork or chicken or whatnot. And the thing is, there’s no difference, ethically speaking, between a cow, chicken, or pig and a cat or dog or a horse, or these other animals that we feel we have a special connection with, so it’s very bizarre. And I really think that this is the foundation of our identity as human beings, this irrational, contradictory way of treating the non-human other. And the last thing I’ll just say is, and I’m thinking about this more and more, I think that the animal system and the way we relate to other beings in this way vitiates any claim that we might have to be moral beings. Because there are thousands of years of moral philosophy, going back to Aristotle and even before, but if you take this issue seriously, as I think we all have to, then you’ve got to wonder what it means to be a moral person in a context of radical evil, in which everybody participates in it.

Robinson

I have to ask you to elaborate here a little bit. You’ve used, and in the book you use, terms that I think are going to cause people to recoil at first. In the book, you talk about tolerance of slavery, and you talk about the Holocaust. You’ve used the words “radical evil” there. You’ve compared the way that we treat animals to pushing an elderly person down the stairs. You’ve said the animal economy today, which is the quote we began your print interview with, is the greatest system of mass violence and injustice in the history of the world. These are charges that are so strong and so at odds with what people think in their day-to-day lives. I’ll ask you to defend the central claim before we get into more of the delusions—to lay out the basic case that we are complicit in a kind of radical evil through the way we treat animals.

Sanbonmatsu

Well, look, it was in 1871 that Darwin wrote The Descent of Man, and then he followed that up with a book a year or two later called The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals. And Darwin argued that there is basic ontological evolutionary continuity between humans and other animals and said that other animals also have reason and emotions. And he demonstrated this empirically, and we have almost 150 years of scientific evidence backing him up. Especially in recent decades, we see that other animals are simply not these irrational, stupid, worthless beings. So that’s number one: that these other beings that we view in these kind of stereotypical ways as crude, primitive, thoughtless beings who don’t experience temporality—they live in the eternal Now, and there’s really nothing going on in terms of their existence. It’s completely false. That’s number one.

And number two, the scale of what we do—the intensity, the ferocity of what we do to other animals—really beggars description, and that’s why I and others reach for these analogies of genocide or slavery. Although slavery is not actually merely a metaphor, the fact is that historians believe that human slavery was modeled on and adopted ideological and technical aspects of the prior so-called domestication of animals in the Neolithic period, 10,000–11,000 years ago. So if you look at the scale, we’re talking about 80 billion land animals, mostly mammals and birds, being killed every single year by our species. And then at sea, about two to three trillion marine animals. The whole ocean is being wiped out—conscious life is being dragged out of the oceans and killed, destroying the web of life within the oceans, and none of it is necessary. So that’s why I think this is a particularly troubling dimension of our existence, because we’ve built our whole mode of life, really materially, around this mass unjust violence.

Robinson

It’s interesting what you say about slavery, because we do think one of the worst things you can do to a person is to dehumanize them or treat them as an animal. And then you think, but what about treating animals the way we treat animals? And then there’s that first thing that you mentioned, the inner life of the animal; we just have to set it aside. There was a recent article by a contributor to Current Affairs about fish pain. The way that, as you mentioned, Darwin was very open about saying, of course, other animals have emotions and feelings in their lives. But for so many years, people just repeated the canard that fish didn’t experience pain because we didn’t want to confront this basic fact about the world that would lead to this very disturbing moral conclusion that you come to.

Sanbonmatsu

I’ve been reflecting on the fact that after decades of careful research and interventions by philosophers, cognitive ethologists, primatologists, and field biologists like Marc Bekoff and so forth, they’ve shown that other animals are very much like us in fundamental ways, in terms of their psychologies, susceptibility to trauma, and their desires for a life that’s meaningful and fulfilling for them. Despite that, there’s this disconnect between all of that and what we see in the mass media, including the news media. I read the New York Times every day, and every day there’s some ridiculous article that simply repeats these canards, as you call them, like myths about other animals being stupid, worthless beings. Hegemony works this way. It has to be continually reinforced. It’s not one and done. You don’t just set up a system of mass exploitation and killing, and it just goes and goes. Because humans understand. We’re not completely ignorant of the fact that other animals are not things. They’re not like pencils and computers; they have something else going on. So to have this violence reiterated, you have to reiterate the ideological rationales for it. And that’s why I call my book The Omnivore’s Deception, because there’s a lot of deception involved.

Robinson

Let’s get into that a bit. The title of your book is a play on Michael Pollan’s bestseller, The Omnivore’s Dilemma. So tell us what you think about these deceptions, these ways in which we lie to ourselves or convince ourselves that we can be ethical and preserve the system relatively the way it is.

Sanbonmatsu

I think anyone on the left, broadly speaking, understands that there are these huge corporate powers worth billions and billions of dollars that propagandize the public and keep us addicted to various commodities that are unhealthy and destructive, socially and ecologically. And that’s the nature of capitalism, to sunder the link between consumption and production, at least in the way that we perceive the production cycle. So that’s obvious. Tyson Foods, JBS, Purdue, McDonald’s—we all understand, I think, that these companies have the power of the Death Star. They have the huge budgets for manipulating mass opinion. But I don’t go after “factory farms” in my book. And I really think that’s important to mention. This is not a critique primarily of so-called industrialized agriculture. It’s a critique of a way of relating to nature and other beings that goes back thousands and thousands of years, long before Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle.

There are two other forms of deception. One is, as you mentioned, Michael Pollan, Temple Grandin, Barbara Kingsolver, and scores and scores of critics—I mentioned just the prominent ones—who tell us that we can, in fact, continue these practices but do it in a kinder, gentler, more compassionate way. We’ll kill them with kindness. We’ll raise animals in a loving way, and then they’ll only have “one bad day,” which is when their throats are cut or they’re shot in the head. That’s a lie, because other animals do suffer, even on smaller farms. They have lives that have integrity and should be respected. But then none of this could gain traction without the third form of deception, which is self-deception, or what Jean Paul Sartre called bad faith, mauvaise foi, and self-deception. We basically hide the truth from ourselves. I sometimes say to my students, “How many of you would think of yourselves as seeking knowledge?” And everyone raises their hands. Homo sapiens—we want to know. We’re curious. Then I say, “Well, I’m going to show you, before you go to lunch, some atrocity videos of animals being killed and mutilated in the animal agriculture industry. How many of you would like to see that?” And no one raises their hand, sensibly, because we don’t want to see suffering. We certainly don’t want to feel like we’re complicit in it. So Michael Pollan’s books would never have become the enormous bestsellers that they have if it weren’t for this need that people have to feel vindicated in their choices and justified in their behaviors. So this whole discourse of humane meat is enabling people to go through their lives with essentially a bad conscience and never having to examine it.

Robinson

And if we’re going to defend something as good and moral and not a problem, isn’t it a little bit odd that we would go to great lengths not to look at it, not to see it, not to ever have to be close to it? Doesn’t that suggest a little bit that we have some kind of discomfort with the arguments that we’re making in its defense?

Sanbonmatsu

I think so. Otherwise, how could we explain the animus that people have towards vegans? There’s that joke: How do you know when there’s a vegan in the room? Answer: Because they’ll tell you. Even to say, “I don’t want to participate in this system of evil and violence and suffering,” people go crazy just hearing that. That’s too much. Even that’s too much, let alone, well, that we should abolish these systems. Governor DeSantis issued an executive order last year, warning Floridians that there was a global conspiracy of elites to take away their meat. So this has become a flashpoint in the culture wars too. It makes sense, because meat-eating is so closely bound up with our identity and with gender, class, and so forth, that it has to be defended, and it is being defended by the right.

Robinson

I found that very bizarre when DeSantis went on his lab-grown meat ban kick, because here we have what should be a win-win solution in a certain way. If you like the taste of meat, if you like eating it, you can have the same experience, but without the suffering of a conscious creature. The right’s response to that was basically no, without the suffering you don’t have meat, which is somehow impermissible. How do you explain that? What’s going on there?

Sanbonmatsu

Well, I’m not a big fan of cellular or synthesized meat. I have a website I cultivate called cleanmeat-hoax.com, and one of the things that I and other scholars on that site talk about is the fact that meat is not like any other commodity. It is not like buying cookies or automobiles. There’s a whole mystique to it. And so, as you say, the domination—the assertion of human superiority over another living being, the killing of the other being—is central to the whole aura of meat. It’s what lends it its authenticity. I remember Michael Pollan was asked some years ago, “What do you think about synthesized meat, cellular meat? Would you eat that?” And he was like, “No, thank you.” He gave this kind of sneering “of course not, that’s disgusting.” Of course it’s not considered disgusting to raise animals in captivity, sexually mutilate them, steal their young, causing trauma to the mothers and the babies, and then brutally kill them while they scream. That’s not considered disgusting. But for me, one of the main problems with the so-called clean or synthesized meat discourse is that it’s presenting a false solution to the problem, because there’s no way to scale that up to current scales of production. You need to convince people that what we’re doing is simply the wrong way to live a human life. That is to say, in dominating and killing other beings. It isn’t a taste issue. There’s plenty of good stuff to eat. We don’t need to eat cellular meat.

Robinson

It’s striking to me how much work the evasion of discussing the issue does. Once you start to have the philosophical argument—and you probably found this when you were writing this book, because you’re making a philosophical case that this is deeply morally wrong—you’ve probably run into what I’ve certainly run into, which is that you don’t have that much intellectual opposition. So a lot of the time, the cases that are made in defense of it are so philosophically weak that you can demolish them very quickly. They’re just pure uses of, as you point out, the naturalistic fallacy, which is that because people have done this, this is good. Well, we know in any other context that wouldn’t fly as a robust philosophical argument; you can’t get away with that. And then you find that the actual defenses are, intellectually, it’s almost like they’re not even trying. They’re depending so much on just, well, let’s just not have the conversation—let’s just not talk about it.

Sanbonmatsu

Absolutely. Look, I’ve been studying this for decades, and for 40 years, really, since I became a vegan and talked to thousands of people, there are no good arguments for what we do to other animals. There just aren’t. I haven’t come across a single one. But it doesn’t matter. And I say in my introduction that I don’t spend a lot of time actually going through the different moral theories of animal rights. There have been thousands of books on this subject. Pythagoras, who gave us the Pythagorean Theorem, left behind a series of vegetarian cults that lasted for centuries. Shakespeare was even making jokes at the expense of vegetarians in some of his plays—they were then called Pythagoreans. So there’s a lot of water under the bridge. There are a lot of great books. In 1894, Henry Salt, the English social reformer and feminist, wrote a book called Animals’ Rights. There are plenty of robust intellectual arguments, but this isn’t about arguments. This is about a mob mentality. This is about a kind of lust for violence and superiority and domination, and it’s all unexamined. I think that’s the kind of thing that’s interesting psychologically and politically: that people have this weird blind spot. People who are otherwise anti-racist and socially justice-oriented but will die on that hill in defense of the meat on their plate. That’s what I see.

Robinson

I often find, and you might have found too, that when you speak to people who eat meat, they say, “Well, obviously I agree that it’s wrong. I do it, but I’m with you intellectually. I do not need you to convince me that it is right to be a vegetarian or vegan. I understand it. I’m not that comfortable with it, but you know...” And what you’re saying here is, well, I’m sorry, but that’s not permissible.

Sanbonmatsu

Yes. I have to say, I had this interview about my book a couple of months ago with someone, and we went through this thing for an hour and so forth, talking about the book. And then he said at the end—he got personal—“You should know that I’m not going to change my diet. So what’s your final message? What can I do to help to eat more humanely?” I said, nothing, you can’t do anything—that’s the issue. You can’t mealy-mouth your way out of it. But people just—again, I feel like this issue is not like any other issue. Because they’re authorized by the mob. I’ve used that word twice, but for a reason. Jean-Paul Sartre, in Anti-Semite and Jew, which is a very important kind of existential phenomenology of antisemitism that he wrote after the war, talks about, well, what is antisemitism? It’s not just a prejudice against Jews. It’s an entire life project: the antisemite gets his or her identity out of hatred of all Jews. And in the same way, the speciesist, for lack of a better word—and that’s most of the human race—is deeply, deeply committed to the idea that we’re allowed on this planet to do what we like to whomever we like, and pretty much whenever we like. So it becomes an existential issue and an existential threat when you or I or someone else just asks for a kind of intellectual distance and a serious ethical reflection. It’s kept at a distance by everybody.

Robinson

It’s a totally different issue, but I was writing yesterday and was thinking about this conversation we were going to have today. I was writing about the Saudi government’s killing of Jamal Khashoggi and the way that United States presidents Biden and Trump both kind of covered up or downplayed the murder because they just felt the partnership with Saudi Arabia was too important to lose. And even though it was a very obvious, clear-cut moral issue—that you shouldn’t have a partnership with a country that murders dissidents—if we confront the issue directly in plain language, clearly and simply, we understand that it’s deeply morally wrong what Joe Biden did, which was to fist-bump Mohammed bin Salman. But there was this sense that, well, the convenience of selling them weapons and doing oil deals with them was so important that maybe we could just set aside the moral issue. And so it seems like this is the ultimate version of that, where the implications of confronting the simple and the obvious are so radical. And I think climate change is that way too, that the science leads you to places that are so inconvenient for so many entrenched interests that instead of saying the obvious, we’re going to try and contort or evade it any way we can. Maybe you could comment on that.

Sanbonmatsu

Yes, sure. Oh my gosh. I’m an old guy, and I’ll tell you, I’ve been studying these issues—American foreign policy and war and feminism and animal issues—for my whole adult life. And I’ll tell you that I’m so alarmed by what I see as a kind of erosion of a baseline sense of moral decency in the individual and societies at the collective level. Internationally, we have a live-streamed genocide in Gaza that goes on for two years, and there’s no pushback from the leading states about it. In fact, they’re all complicit in that. And then, as you say, the murder and dismemberment of Khashoggi, and they had an audiotape of that occurring—Turkish intelligence got hold of that. And yet, the CEOs of Dell and Ford and all the top CEOs were at the luncheon or dinner for bin Salman with Trump.

So we’re in a kind of post-shame environment, and I think it’s very concerning for social movements, because what did Gandhi talk about? Satyagraha: speaking truth to power. If truth doesn’t matter, or fundamental principles of right and wrong and common decency no longer matter, and I really don’t think they do matter to most people—and I say this teaching undergraduates—I don’t even know what the basis is for building a social movement. And I know there are oppositional movements, and so I haven’t given up all hope. But especially with AI now, what I’m seeing among students is widespread cheating, and I don’t believe it’s simply a question of convenience. I think that students just don’t care that they’re engaging in a behavior that’s unethical because they’ve simply been taught their whole lives that the only thing that matters in this capitalist economy is getting ahead and succeeding in the terms that are given to them by the system. The idea of honor, the idea of duty, is just foreign to them—foreign to many people. So that’s what really worries me. And the last thing is the war on empathy. Elon Musk has described empathy as the greatest threat to Western civilization, and he may be right, because, in fact, if you begin to have compassion for those people being taken away by ICE, for Khashoggi’s family, and for the domestic workers in Saudi Arabia who are being abused by their employers, well, you’re then going to begin to unravel some of the power structure. The interesting thing about the Epstein files is that they’re exposing the total corruption of the intelligentsia and the ruling elite.

Robinson

And of course, you might end up having compassion for nonhuman animals. The moment you have that, and start to think consistently, and stop accepting arguments about pigs that you wouldn’t accept if they were made about your dog—the first thing you do as you clear away the mental cobwebs is you go, “Well, hang on a minute, would I accept this argument in another context? Oh, no, I would not think torture was acceptable in that context.” When you start to do that and work it through, you come to a place that people don’t want to go. And you’re going to take them there in this book. I’ll warn them: you say that openly. You say, “I’m not going to use any euphemisms here. We’re going to talk about things as they are, and it’s going to take you to someplace very uncomfortable that you probably don’t want to end up.”

Sanbonmatsu

Well, again, as someone who teaches moral philosophy, I think this is the problem. Most people don’t place a high value on moral consistency. They’re willing to engage in a kind of group or herd mentality and behavior if it helps them avoid that discomfort. I would say there’s safety in numbers in many situations in life, in a disaster and so forth, but there’s no safety in numbers when it comes to ethics. Just because everybody else is doing something, let me tell you, it is not any kind of sanction for your behavior. Slavery was naturalized for thousands of years. Before it was racialized in the early modern period in the ancient world, it was simply taken for granted, and there wasn’t even the possibility of dissent. People didn’t even think to question the enslavement of other human beings, but that didn’t make it right. It simply meant that people were kind of clueless, and that’s what’s happening today. And they don’t even understand that their own material comfort, their own ability to survive on this planet, is linked to the fate of all the billions and trillions of animals that we’re killing because we cannot survive on a planet that doesn’t have insects, for example. We’re living through the insect apocalypse, with 80-90 percent population crashes of invertebrates around the world. We won’t be able to grow crops without pollinators.

Robinson

Yes, that appeal to self-interest might be the only thing that works.

Sanbonmatsu

Well, I do talk about the ecological, but I don’t think so. I don’t think appealing to self-interest will work, to be honest. Because there’s always some workaround that people can rationalize. There’s a wing of the movement called the abolitionist wing of the animal movement, and so I and others are in favor of abolishing root and branch these systems, these economies, these modes of economic production that are inimical to life on the planet Earth. But yes, appealing to self-interest is like being in a village outside Auschwitz in the Polish village and saying, “Oh, I’m getting soot in my eyes; we’ve got to stop those crematoria because they’re inconveniencing me.” That’s the wrong approach, I think.

Robinson

Well, you must have thought a bit about paths forward. You’re still writing and lecturing on ethics and morality, so clearly you think there’s a point to doing it. What we’ve laid out so far is somewhat dispiriting, because we’ve suggested that, first off, it is not easy for human beings to confront things that are very morally obvious, and we construct many rationalizations and deceptions. And second off, it might be getting worse in the age of Trump, where we don’t even have common moral standards to appeal to. You pointed out in a quote that we cited in your interview that the animal rights movement itself really has not had much success at all in changing the public’s view that killing and eating animals is natural and right. The system is more brutal every year than it’s ever been. So where do we start, given where we are?

Sanbonmatsu

Yes. Oh gosh, we’re out of time. My first book, The Postmodern Prince, was an attempt to understand why it’s become really hard to conceive of left social movement strategy and organization. And I think that we have to come back to that. We’re living in a historical period where it’s very hard to get headwinds against any of these global structures of oppression and authority and violence that are destroying life. So it’s a very difficult problem to try to solve. I will say that, as I argued in that book, and I still believe this, we need a counter-hegemonic movement that’s able to exert what Antonio Gramsci termed moral and intellectual leadership over society. It’s not just about seizing the state, nor is it, as consumer-oriented vegans would say, winning one vegan over at a time—this individual solution. We’re talking about entrenched systems that need to be challenged frontally as well as culturally and intellectually. So what we need is a mass movement that tackles both the global capitalist division of labor—I hate to say that, because that’s a big ask—but also the animal system that is its basis. And the leftists do not want to hear that, because they don’t care about animals, and in fact, they’re among those anti-animal rights people that you can find. But a socialism based on mass violence and injustice is not a socialism we should get behind. So I guess in addition to everybody absolutely moving towards a plant-based diet immediately and telling others to do that, we need a movement capable of reconstituting the state and the basis of production.

Robinson

You made a remark that I imagine some of our leftist readers may find provocative, which is that leftists have been terrible on animal rights. But if anyone wants elaboration and substantiation of your claim there, they should pick up our Animals issue and turn to Troy Vettese’s article, “The Left Has Failed Animals,” where he goes through the history and shows that it was not always that way. Many early socialists were very pro-animal rights, but animal rights sort of disappeared from the left’s agenda over the course of several centuries. He provides a very compelling case that the left needs to reincorporate an understanding that this is another form of domination, that if the core of our politics is overthrowing every form of injustice and exploitation, we have to have animals at the center of that.

Well, we truly appreciate you coming on, John. And just to give a personal plug here for this, it’s such a beautifully clear and forceful work of philosophy that is both empirically grounded and also rich in theory and in quotation. It’s very readable for a general audience, even though it’s out with an academic press. Your writing in here is just beautiful. And I think it is a difficult read. I think a lot of people will be reluctant to dive into this book and are going to want to throw it away, but I would encourage them not to.

Sanbonmatsu

Thanks, Nathan.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.