How American Evangelicals Stole the Legacy of Anti-Nazi Resistance

From pulpits to Project 2025, the Christian right has recast the German resistance—and this time, they're the martyrs.

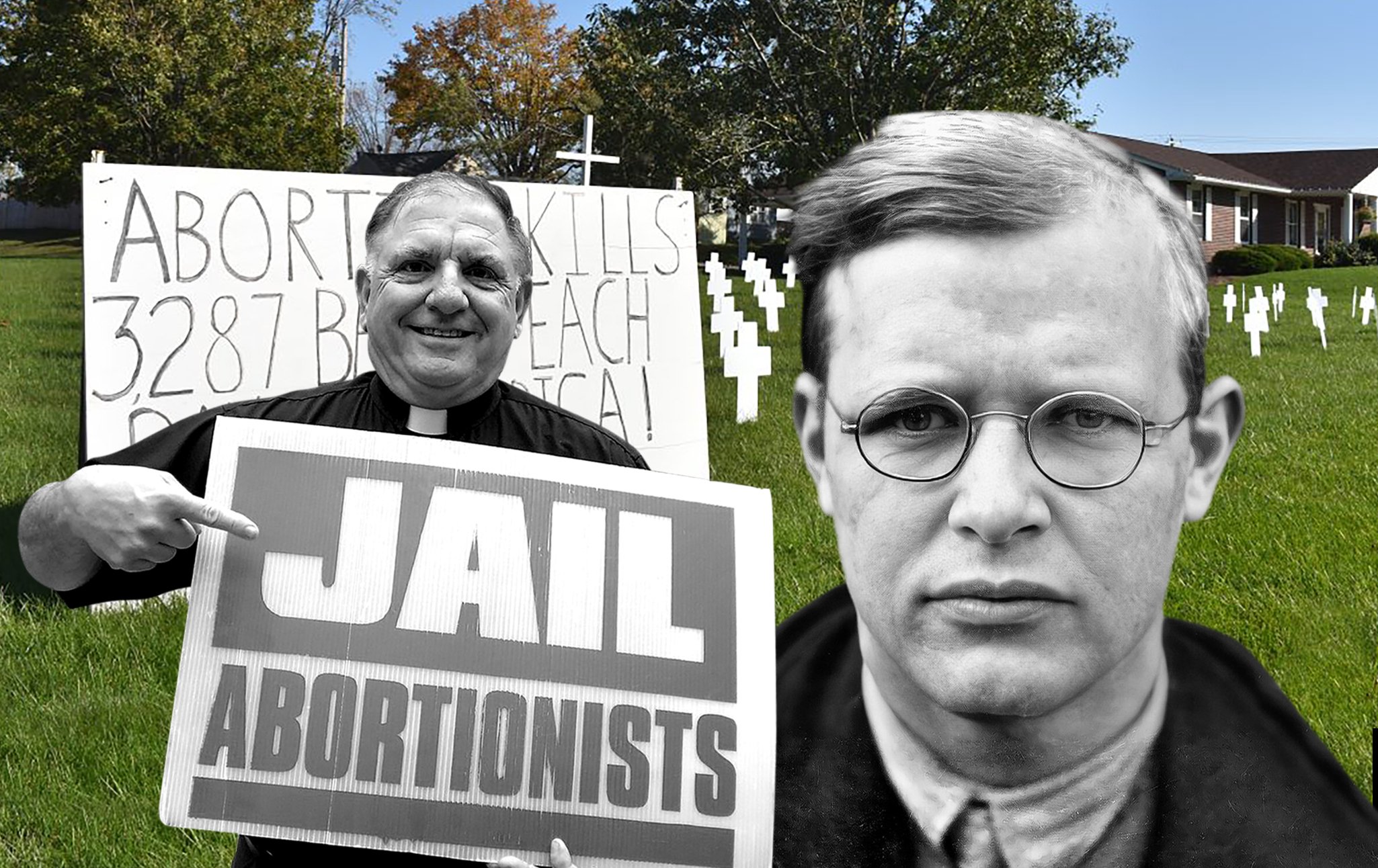

On New Year’s Day 1943, the German pastor and resistance fighter Dietrich Bonhoeffer sent a letter to his circle of close friends and compatriots. For years, Bonhoeffer and a group of dissenting clergymen known as the Confessing Church had struggled against the Nazi takeover of religious life in Germany. More recently, Bonhoeffer had joined German military intelligence as a double agent, attempting to contact the western Allies on behalf of the German resistance movement. Only three months after Bonhoeffer wrote his letter, he was arrested by the Gestapo and, in April of 1945, murdered in Flossenbürg concentration camp. “We have been silent witnesses to evil deeds,” he wrote. “We have been drenched by many storms. We have learned the arts of equivocation and pretense. Experience has made us suspicious of others and kept us from being truthful and open… Are we still of any use?” Eighty years after Bonhoeffer was killed, the answer to his question seems to be “yes”—though not any use that the pastor himself could have imagined.

In its 12 years in power, the Hitler regime killed more than 70,000 of its own citizens for political “crimes”: not just active resistance fighters, but also ordinary people who simply said or thought the wrong things. Many of these resisters—such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the young students who belonged to the resistance group known as the White Rose—are household names in Germany, considered paragons of moral and political courage. But in America, these anti-Nazi martyrs are increasingly becoming objects of fascination on the evangelical right.

This is a particularly odd phenomenon to be taking place in the U.S., where many people don’t know that there was a German resistance at all. But in recent years, right-wing evangelicals have taken to comparing themselves to the Germans who fought Hitler, claiming that they embody the same virtues of courage and self-sacrifice, and face the same persecution and martyrdom. Beginning on the fringes in the 1990s, this dubious historical comparison has since gone mainstream on the Christian right—and evangelicals are churning out books, movies, and online agitprop to make it work.

If one pays close attention to the rhetoric of the American evangelical right over the last five years or so, one sees references and comparisons to the German resistance cropping up all over the place. Last year, a blockbuster evangelical-produced Bonhoeffer biopic drew widespread criticism for falsifying the pastor’s life story. Multiple separate evangelical groups named after the White Rose now rail against everything from vaccines to abortion. Bonhoeffer even holds the dubious distinction of being cited—and severely misrepresented—in the preface of the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025.

Today’s evangelical fixation on the German resistance was not the product of any sudden development or discovery. Already in the 1990s, the most extreme sectors of the Christian right had latched onto Dietrich Bonhoeffer. The latching had little to do with Bonhoeffer’s actual work or theology (which was generally quite humanist and progressive), but more with what he represented: a godly and forcible stand against evil. The Army of God, an active Christian terrorist group responsible for the murder of numerous abortion doctors, is one such organization. The group follows what is known as “leaderless resistance,” a strategy in which members rarely communicate with each other in order to avoid prosecution—but they do have a website, which openly instructs followers to commit violence.

The site is filled with manuals by convicted terrorists like Michael Bray, who was sentenced to prison for the planned bombing of several women’s health clinics, and Paul Jennings Hill, who shot and killed an abortion doctor and his bodyguard in 1994. It also routinely references the German resistance. One webpage features an anonymous interview between an “underground leader of the American Holocaust Resistance Movement”—or Army of God (A.O.G.)—and someone who calls themself “the Mad Gluer” (M.G.), discussing specific methods of terror:

M.G.: What do you recommend that concerned citizens do at this time?

A.O.G.: Every Pro-Life person should commit to destroying at least one death camp, or disarming at least one baby killer. The former is a relatively easy task - the latter could be quite difficult to accomplish. The preferred method for the novice would be gasoline and matches.

Throughout these conversations, time and time again, the same name appears:

M.G.: O.K. Do you have any special heroes who give

you inspiration ?

A.O.G.: Well, there are many heroes of the Faith throughout history, but one of my personal favorites is Major Von Gersdorf.

M.G.: Who worked with Bonhoeffer, right?

A.O.G.: Yes. He was the guy who always wore a trench coat - a loaded trench coat. Once, when the Resistance was planning a Putch, Von Gersdorf had bombs, one in each pocket, that he was going to detonate in Hitler's presence. (…)

M.G.: That's quite a story. I think that here must be some Army of God persons who have that kind of resolve and commitment.

Another webpage hosts a book titled In Defense of Others: A Biblical Analysis and Apologetic on the Use of Force to Save Human Life. Bonhoeffer’s name appears in the text several times, with the author suggesting that Bonhoeffer—who understood the need to use force to stop the Nazis—would understand the need to use force to stop abortion.

The warped Bonhoeffer story reached a wider audience in 2010, when conservative radio host Eric Metaxas published his popular biography Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy. The book was named Christian Book of the Year by the Evangelical Christian Publishers’ Association, and became a New York Times bestseller. Nonetheless it was widely critiqued by Bonhoeffer scholars, who accused Metaxas of misrepresenting Bonhoeffer’s key ideas on religion—his pacifism and his advocacy of what he called “religionless Christianity”—in in order to make them more palatable to an American evangelical audience.

But if Metaxas was mainly misrepresenting Bonhoeffer’s theology, it undoubtedly served political ends. The right’s drift toward a political-theological fusion commonly called Christian nationalism—which has found new purchase in the Trump era—can be glimpsed in Eric Metaxas’s own personal and political evolution. In the years following the release of his Bonhoeffer biography, Metaxas had begun speaking about a concept he called the “Bonhoeffer moment”—the point at which a Christian can no longer accept the dictates of an “evil” government or society and has a duty to resist, even using means that would previously have appeared unchristian (read: violence). Once Christian nationalism began finding wider and more explicit support on the American right within the last five years, the distorted interpretation of the German resistance pushed by Metaxas reached a fever pitch. Metaxas himself, no longer content to just write books, waded into the fray surrounding the 2020 election: on December 12th, 2020, Metaxas emceed a “Jericho March” rally on the National Mall in Washington DC, one of the two key rallies which the House investigative committee said helped “pave the way for January 6th.” (Metaxas is also the author of the MAGA children’s books Donald Builds The Wall and Donald Drains the Swamp, and served as a writer for the cartoon program Veggie Tales.)

2020—and the bizarre whirlwind of the pandemic which consumed that year—seems to have been a turning point in many respects. The effects of isolation and the mediation of life through screens and social media undeniably siloed off large portions of the population from consensus reality. Lockdowns, and later vaccine mandates, led many Americans to earnestly believe that they were living in a totalitarian society. It wasn’t long before comparisons were drawn to that ultimate totalitarianism, Nazism—the usual hyperbolic Godwin’s law stuff. But if your enemies are Nazis, and you imagine yourself as bravely standing up to their totalitarian methods—what does that make you?

At the height of the pandemic, stickers and flyers began appearing across the United States—but also the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, and elsewhere—bearing a familiar name. An anti-vaxx group calling itself the “White Rose” had begun a widespread campaign of leafleting and disinformation, attacking Covid lockdowns and vaccines as resembling the repression of the Third Reich. The name choice, conversely, implied that anti-vaxx activists were the present-day equivalent of the group of German students who had risked their lives to distribute anti-Nazi leaflets in 1942 and 1943. While the group was not outwardly linked to an evangelical organization and did not advertise a religious orientation, new members found the group’s Telegram channel full of evangelizing and appeals to accept Jesus Christ. (Indeed, a 2021 study found that “One of the strongest predictors of anti-vaccine attitudes in the U.S. is Christian nationalism—a U.S. cultural ideology that wants civic life to be permeated by their particular form of nationalist Christianity.”) By 2021, the group’s Telegram channel had 41,000 members.

The real White Rose was led by brother-and-sister university students Hans and Sophie Scholl, their friends Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, and Alexander Schmorell, and University of Munich professor Kurt Huber. This group, with help from other friends and confidants, wrote and distributed thousands of anti-Nazi leaflets—initially in Munich, and then later across Germany—calling on the German people to rise up. On February 18th, 1943, the Scholl siblings threw a cascade of leaflets over the railing in one of the main stairwells of the University of Munich. They were caught in the act by the surprise appearance of a university janitor, who reported them to the Gestapo. In the space of four days, Hans and Sophie were arrested, tried by “Hitler’s hanging judge” Roland Freisler at a special session of the kangaroo People’s Court, and beheaded at Stadelheim Prison in Munich. The rest of the group soon met the same fate.

Needless to say, no one who put up anti-vaxx flyers in American cities was ever guillotined. Somehow, in a fever-dream culture of imagined persecution, getting barred from a restaurant or being on the receiving end of a Twitter pile-on becomes as bad as getting beheaded.

This particular genie wasn’t back in the bottle once Covid lockdowns were lifted. In 2022, another American group appropriating the White Rose name sprung up—this time targeting not Covid lockdowns but abortion. The “White Rose Resistance” anti-abortion group was founded in 2022 by Seth Gruber, an evangelical pastor who claims that he was “saving unborn babies from abortion while still in his mother’s womb.” His book The 1916 Project: the Lyin’, the Witch, and the War We’re In purports to “expose the evil history of Margaret Sanger, Planned Parenthood, and the Abortion Industrial Complex.” The book received a glowing review from Charlie Kirk, who said that the book “lays out the path toward abolishing abortion.”

Gruber claims that the “White Rose Resistance” is the fastest-growing pro-life group in the United States. The group mobilizes its supporters for anti-abortion demonstrations (including the annual March for Life in Washington DC), and promises “pro-life encouragement and action steps” for those who join their email list. The group’s website, decorated with pictures of Sophie Scholl and outlines of pregnant women, declares that, “The White Rose Resistance was launched after the overturning of Roe v. Wade in 2022. 80 years after Hans and Sophie’s execution, America finds itself facing the same evils and same apathy today.” Gruber describes abortion as a “silent holocaust” that has killed “65 million unborn human beings” since the Roe v. Wade decision. It is of course deeply ironic that Seth Gruber founded his “resistance organization” immediately after he and his ilk had succeeded in making their personal preference the law in large parts of the country; even in victory, the evangelical right imagines itself as the persecuted underdog.

It only gets stranger from there. The group’s account of the real-life White Rose—to be found front-and-center on their website—is shot through with factual errors, though these errors are themselves very revealing about how the evangelical appropriators of the German resistance manipulate the history to fit their agenda. For one thing, Gruber’s group describes the actual White Rose as a “collective of Christian students” who were motivated by religious fervor to resist the Nazis. While Christianity was an influence on some members of the group—including the Scholl siblings—it was far from the only one. Indeed, the group’s first leaflet was full of references to Germany’s secular intellectual tradition—Goethe and Schiller, for instance—rather than scripture, contrasting Germany’s civilized past as a “land of poets and thinkers” with the barbarism of the Hitler regime. Only one of the group’s six leaflets (the fourth) dwells extensively on religious themes: “Every word that comes from Hitler’s mouth is a lie,” the leaflet reads. “When he says peace, he means war, and when he blasphemously uses the name of the Almighty, he means the power of evil, the fallen angel, Satan.” One would like to know what right-wing evangelicals might think of the assertion in the White Rose’s next leaflet that, after the overthrow of the Nazis, “the working class must be liberated from their debasing slavery by a reasonable form of socialism.”

The problem, though, is that in all probability Gruber or those like him have never read the actual White Rose leaflets. If they had, they would have found a group of brave, honest, articulate, brazenly intelligent, well-read, clear-sighted young people, steeped in the humanistic literary and intellectual tradition of their country, and capable of penning words of such poetic moral force that they still resound eighty years later like the clang of a sword. But they would not find warriors for whatever god Seth Gruber is selling. Are these distortions the product of willful misrepresentation, or just sloppiness resulting from profound ignorance and incuriousness?

For his part, Dietrich Bonhoeffer believed that it is near-impossible to argue with the truly ignorant. “Against stupidity we are defenseless,” he wrote in Letters and Papers from Prison. “Neither protests nor the use of force accomplish anything here; reasons fall on deaf ears; facts that contradict one’s prejudgment simply need not be believed… Never again will we try to persuade the stupid person with reasons, for it is senseless and dangerous.”

Right-wing evangelical treatments of Bonhoeffer’s own life have toed the line between ignorance and wilful misrepresentation, before veering pretty definitively into the latter in the past year. Bonhoeffer has the dubious distinction of being mentioned in the preface of the infamous Project 2025, the handbook for a right-wing and Christian nationalist takeover of America’s institutions in the wake of Trump’s reelection:

That’s why today’s progressive Left so cavalierly supports open borders despite the lawless humanitarian crisis their policy created along America’s southern border.

They seek to purge the very concept of the nation-state from the American ethos, no matter how much crime increases or resources drop for schools and hospitals or wages decrease for the working class. Open-borders activism is a classic example of what the German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer called “cheap grace”—publicly promoting one’s own virtue without risking any personal inconvenience.

However, the authors of Project 2025 seem to so severely misunderstand the concept that the mention of Bonhoeffer appears as a complete non-sequitur. The cheap grace idea comes from Bonhoeffer’s 1937 classic The Cost of Discipleship, in which he says that Christians have become too averse to self-sacrifice and standing up for moral principles, and instead rely on God’s grace and forgiveness when they do not act with moral courage. What this has to do with open borders or woke environmentalism is beyond me.

Things only got worse in the wake of the blockbuster evangelical-produced biopic about the man, titled Bonhoeffer: Pastor. Spy. Assassin. The film was released last year by Angel Studios, the same people who distributed the QAnon-adjacent evangelical child trafficking paranoia film The Sound of Freedom. Bonhoeffer so thoroughly massacres not just the pastor’s life and ideas, but the story of the entire German resistance, that ignorance seems to be off the table as an explanation—it simply must be the product of a wilful campaign to distort the past.

The first thing one sees when watching the Bonhoeffer film is, of course, the Angel Studios logo, followed by the words “This film has been approved by the Angel Guild.” I had to look up what this was; no, it’s not Heaven’s equivalent of the MPAA, but rather a pay-to-play subscription service where evangelicals can pitch in to fund movies—which they call “torches”—that promote their views.

There are parts of the film that are so bad as to be almost amusing; the dialogue, especially, is often laughable. “The Nazis’ rise to power has everyone a little anxious, Dietrich,” Bonhoeffer’s brother-in-law Hans von Dohanyi tells him when the soon-to-be-pastor returns from a seminary sabbatical in America, a full two years before Hitler became chancellor. (This comes after a scene in which Bonhoeffer, suddenly endowed with virtuosic jazz piano skill, leads a big band in a Harlem nightclub. Unfortunately, this never happened in real life.) When Bonhoeffer joins military intelligence, he tries to reassure his Nazi commander of his loyalty by imitating the Nazis’ manner of speaking—which, in the movie’s universe, sounds like it comes from a Darth Vader fanfiction penned by a fifth-grader. “The time has come for Germany to rise and for the rest of the world to bow down. Heil Hitler!” (Everyone else in the room mechanically yells “Heil Hitler!”)

But beneath the hokey writing, the strange directorial choices, and the obvious contortions of historical chronology, there’s something more insidious going on: a wholesale rewriting of the history both of the Third Reich and of the resistance.

For one thing, Bonhoeffer portrays the Nazis as militant atheists enacting some kind of crusade against religion. In a scene following the Nazi takeover, a generic unidentified brownshirt brays from the lectern at a party rally, “The church must clear away all crucifixes, Bibles, and images of the saints, and replace them with our leader’s glorious words. And it must be superseded by the only unconquerable symbol, the swastika!” The film then cuts to images of iconoclastic destruction inside German churches, as Nazis smash religious statues, pull down crosses, and replace Bibles with copies of Mein Kampf. Nothing like this ever happened; it is pure fantasy on the part of the filmmakers. And if the film portrays Nazis as hammer-wielding atheists, it also implies that only Christians fought against Hitler: the film cuts the non-Christian resistance out of the story completely. This is evidenced most directly by the completely ahistorical role it ascribes Bonhoeffer, presenting him as a driving force behind the plots to kill Hitler. We see Bonhoeffer holding secret meetings, rigging bombs, praying fervently for their successful detonation. None of this happened either. The resistance did make numerous attempts to assassinate Hitler, including the 20 July 1944 bomb plot, which was carried out by dissident army officers around Count Claus von Stauffenberg and very nearly succeeded.

But Bonhoeffer was not the mastermind behind this or any other assassination attempt. He was aware of the plots, but that was as far as he got—he was a courier and a moral center for the resistance, but not an assassin. The film writes the military resistance—not to mention the many leftist resistance groups—out of the story entirely; Claus von Stauffenberg is never mentioned, nor the communist Red Orchestra group which also worked within the German intelligence services. If evangelical Christians position themselves as the sole legitimate heirs to the resistance against the most evil regime in history, then surely evangelicals must be correct about other things too, right?

Few resisters survived the war—the German resistance is a movement made of martyrs. And across the ocean there is a movement that devours martyrs hungrily, so hungrily that they seem increasingly ready even to eat up the martyrs of other causes. At least some of this evangelical obsession with martyrdom must be the product of Christianity’s beginnings as a persecuted sect in the Roman Empire: the image of pious Christians allowing themselves to be fed to lions must seemingly repeat itself in every generation. One needs only to have watched Charlie Kirk’s memorial service to glimpse the depth of the evangelical obsession with martyrdom.

To compare oneself to a martyr is to appropriate some of their glory for oneself. And it also allows one to vicariously share in their persecution and suffering—the supposed historically-ordained role of Christians since the time of Christ himself—without having to actually suffer pain and death.

But is there not something more sinister at work here: the laundering of morally questionable causes through the appropriation of uncontestedly righteous ones? From Christian nationalism that seeks to annihilate religious pluralism in America to anti-abortion radicalism that seeks to annihilate the right to choose, figures of rather vile moral provenance are trying to steal a little bit of the lustre of such immortal figures as Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Sophie Scholl. It seems so easy, after all: history has lost none of its power as a source of legitimacy, but consensus reality around the past—as with the present—is breaking down. As it gets easier to spread disinformation about virtually everything, the risks of falsifying history diminish greatly.

It’s nothing new to compare anything one doesn’t like to Hitler and the Nazis. It’s a consequence of the Nazis being the global standard for ontological evil. But comparing oneself to the anti-Nazi resistance is a new kind of valorizing, self-dramatizing analogy: the image of a lone, persecuted individual, standing up against world-historically evil forces and sacrificing one’s life in the process. The evangelical right’s existing fascination with persecution and martyrdom, and these comparisons’ undoubted propaganda value, are more than enough incentive to continue making them.

Perhaps the biggest incentive is that they keep getting away with it. In America, the story of the German resistance is not particularly well-known, but any reasonable person, once they encounter some version of it, would agree that these resisters were brave and admirable people. If an evangelical book or film sells a dishonest form of that story, academics and experts may get annoyed; but, understandably, regular people are not familiar enough with the history to know they’re being lied to.

And through it all, there is a more startling undercurrent: the potential that someone, somewhere, will decide that the best way to imitate these resistance heroes is to go out and kill another human being. Assassinate a politician, blow up an abortion clinic, what have you—if the German resistance was right to kill Hitler, and one believes one’s opponents to be Hitler, what kinds of madness suddenly become permissible? Groups like the Army of God already used this twisted logic before. With political violence in America escalating, and these distorted messages about the German resistance reaching ever-wider audiences, who knows what could happen?

To actually live up to the example of Bonhoeffer and the Scholl siblings is hard—perhaps impossible, given the extreme differences between their time and ours. Conversely, the spirit of our times makes some things very easy: falsification, appropriation, self-dramatization. True courage is rare; but the imitation of it, cloaked in deceit and imaginary victimization, is not. Stefan George, the German poet-prophet, penned fitting words in his 1907 poem about another great knockoff, “The Antichrist.”

In return for what’s rare and what’s hard I create

The simple • a semblance of gold from the clay •

Of the tang and the juice and the perfume.

[...] Caught up in the devilish fake, you rejoice

Will this devilish fake succeed? Time will tell, of course. Dietrich Bonhoeffer himself said that it is impossible to sway truly ignorant people with facts. That may be true for the people who churn out these false histories, but for the people who might be reached by them—if the true story, the real story, reached them first, they might not be so susceptible to the lure of the fake. The story of the German resistance is too important, and too poignant, to be simply ceded to those who wish to manipulate it for their own purposes. Perhaps the misrepresentations, by sheer volume, will drown out the truth. Or maybe they won’t, or can’t.

On that point, other verses come to mind. They were penned by the German-Jewish literature professor Friedrich Gundolf, a follower of Stefan George. (Also a member of the so-called George Circle was a young Claus von Stauffenberg.) As Gundolf lay dying in 1931, he wrote a poem called “Schliess Aug und Ohr” (“Close Your Eyes and Ears”), which was soon set to music and became a standard of the German youth movement in the waning days of the Weimar Republic. The poem, in twelve clipped lines, speaks of a time in which lies abound, in which the endless clamor of events grows so loud that a person can hardly hear themselves think or know what is true. But even in such chaos, Gundolf writes, there is always an inner truth.

It was through the youth movement that Sophie Scholl first heard the song. It soon became her favorite. To this day, it is known as “the song of the White Rose.”

Close your eyes and ears for a while

To the roar of time.

You will heal nothing, and cannot be healed

Until your heart is consecrated.

Your task is to guard, to wait,

To see eternity in a day.

Thus are you already in world events

Imprisoned and liberated.

The hour will come when you are needed

Then you must be entirely ready.

And into the smoking flames

Throw yourself like firewood.

It is a fitting epitaph for her, and all those like her—all those who were really like her.