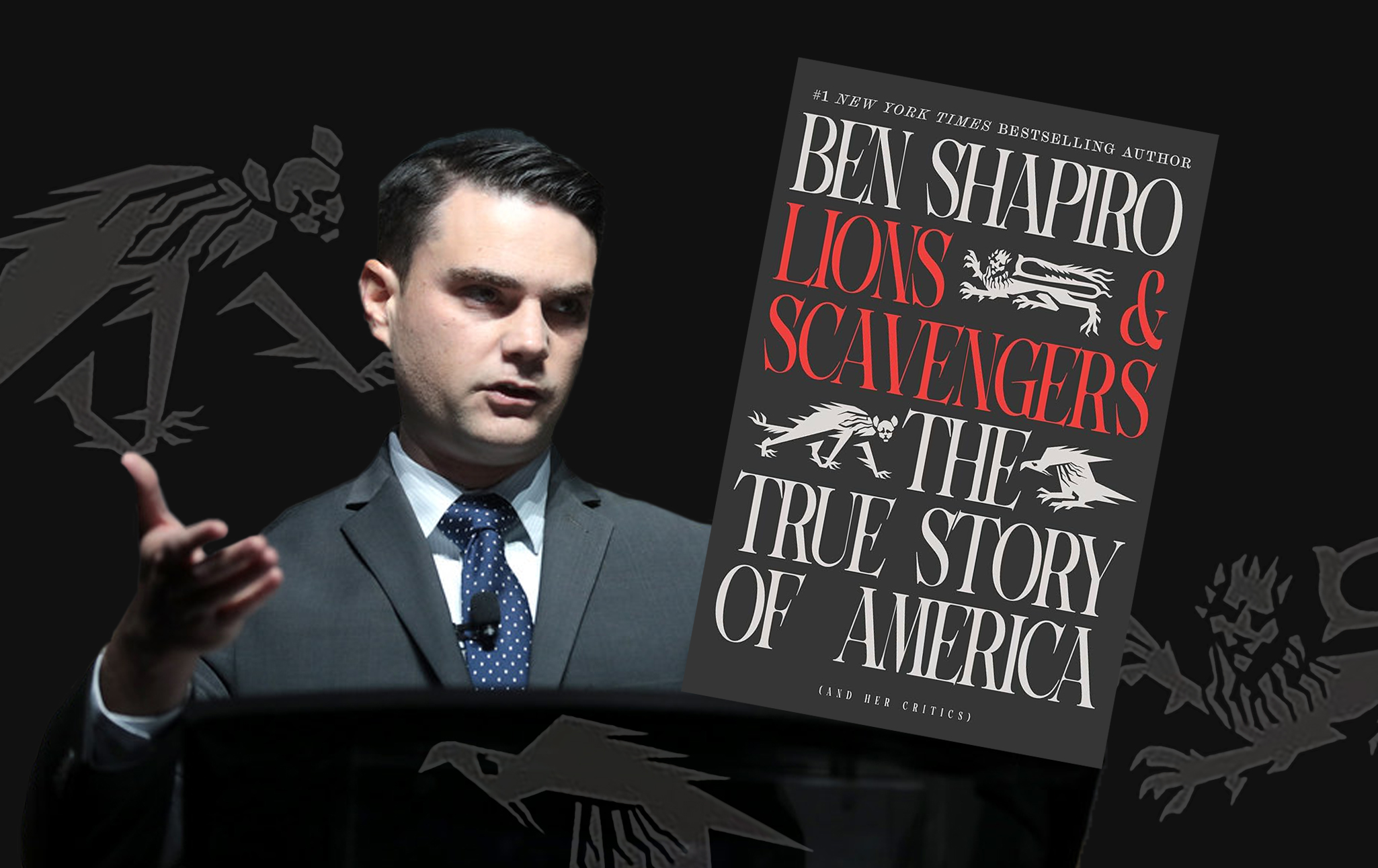

Supposedly, the world is divided into good, noble “lions” and evil, grasping “scavengers.” Guess which one Ben thinks he is?

In patented Shapiro form, everything here is miles wide and inches deep. Reading Ben Shapiro wrestle with ideas greater than Cardi B’s WAP, you’re constantly reminded that this is a grown man who still makes his name “battling” anxious teenage freshmen in YouTube videos. Long stretches of the book have the feel of a first year undergraduate essay in political theory destined to climax in the inevitable end of the semester “professor, is there a way???” email. The book makes you wish he’d respect Smith, Locke, and Hayek enough to leave their work unblemished by bastardization. It would be less insulting to the richness of the Western canon if he’d spend his time discussing the plausibility of black mermaids with Matt Walsh.

Much of Lions and Scavengers has an almost poetic quality to it. Not good poetry, mind you—this is much more of the ChatGPT “a line break after every thought” school. But it’s certainly closer to poetry than actual argument, as a couple of excerpts will show:

We see them.

We see the rivers of humanity, their fists raised, their flags of third-world countries and terror groups held aloft, the hatred in their eyes, climbing our monuments and defacing them, ripping down our flags and replacing them with their own.

We hear them chant for our eradication, their screaming voices raised in ecstatic frenzy, the stamping of their feet as they march in unison against us.

We feel their venom, their senseless and ceaseless animosity, their blame, their shame, their rage.

They are all around us.

These are the Scavengers.

The Scavengers are those who produce nothing, and demand everything.

The Scavengers are those who demand as their right that which has been produced by others; who blame their own miseries, in free societies, on “systems of power” that supposedly rob them of autonomy; who claim that failure is a virtue and success a sin.

They are creatures of envy.

They are creatures of ressentiment.

They are creatures of destruction.

Or try this one:

The Scavengers crowd around the battered Lion.

Our institutions lie in ruins; our borders in tatters; our communities in knots.

The Lion, weary from the exertions of the centuries, bleeds.

The Scavengers snarl and circle him.

The dream of the Scavenger, it seems, will finally come true.

The Lion, it seems, will finally die.

And then it emerges.

It emerges from the belly of the Lion: a low grumbling at first.

It resonates in the Lion’s throat, growing louder with each passing millisecond.

And then, at last, the Lion opens his massive jaws.

He struggles to his feet.

And he roars.

His strength, dormant for so long, still rests coiled in his limbs.

His courage still beats in his chest.

The Lion’s honor is not dead after all.

It goes on and on like this. The “lions” are CEOs, the IDF, Donald Trump, Elon Musk, Ben’s wife, and the people who buy his books but don’t think about them that carefully. The “scavengers” are Marxists, Muslims, pro-Palestine student protesters, Bernie Sanders, AOC, and anyone who ever thought they were owed a living wage. And if you’re thinking “surely it must be a little more complicated than this, the world is more than a children’s fable about good lions and bad scavengers,” reader, we assure you, this is all there is to it. It is a bifurcation even more superficial than the “oppressor/oppressed” binary so many people on the right project into left-wing thinking in order to dismiss it as reductive. In the book’s acknowledgements Shapiro admits Lions and Scavengers wasn’t written with “cold objectivity” but in a “white heat.” Lions and Scavengers feels like a rage post, casting so much more heat than light.

Lions and Scavengers is a perfect encapsulation of Brandolini’s law that the energy required to refute bullshit is orders of magnitude greater than what it takes to produce it. Canvassing all the errors, shrill hyperbole, and emotional grandstanding in Shapiro’s work would require a tome that would outgirth the three volumes of Capital. We know our readers have busy lives. We care enough to not subject you to too much more of Shapiro’s angsty poetry, a la “Family. Community. Nation. Pride. We must all be Lions. Our Pride demands it.” (Okay, no more Shapiro poetry, we promise.)

One thing that becomes clear when reading Shapiro’s book is the lightness of his engagement with the many far more serious figures who are cited throughout his screed. This includes not just those he despises, like Frantz Fanon and Jean-Paul Sartre, but even the authors he invokes positively. Their nuanced and multifaceted perspectives are ignored to make way for Shapiro’s breakneck weaponization of out-of-context quotes.

For example, Shapiro has lots of good things to say about Adam Smith, defender extraordinaire of capitalism. In Chapter Three he cites Smith’s comments in the Lectures on Jurisprudence to the effect that free markets “reward honesty, punctuality, and decency.” Later in the same chapter Shapiro admits a society cannot live on Walmarts alone. It “also requires public virtue.” He notes that Smith “famously understood just this.” Discussing Theory of Moral Sentiments Shapiro approvingly argues “Smith posited that human beings exchanged regard and esteem in the same way they exchanged goods and services.” Much of Lions and Scavengers is taken up with exploring how these public virtues have been distorted, and of course the answer is that it’s largely the left’s fault. If only Smith himself had taken the time in Theory of Moral Sentiments to weigh in on the most “great and universal cause of the corruption” of our moral sentiments and their attendant virtues…

This disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition, though necessary both to establish and to maintain the distinction of ranks and the order of society, is, at the same time, the great and most universal cause of the corruption of our moral sentiments. That wealth and greatness are often regarded with the respect and admiration which are due only to wisdom and virtue; and that the contempt, of which vice and folly are the only proper objects, is often most unjustly bestowed upon poverty and weakness, has been the complaint of moralists in all ages.

Were Smith alive today, he might note that Lions and Scavengers—which rhapsodizes about how “wage-workers certainly provide a valuable service[…] but technological and material progress is built on the back of the entrepreneur, for it is the entrepreneur who risks it all to build something”—contributes a lot to the “corruption of our moral sentiments” that Smith warned about, that instinct to “admire, and almost worship, the rich and the powerful.”

Smith would also take issue with Shapiro for his inattention to the harms of capitalism. Smith is known as a champion of the division of labor, but he lamented that it was making workers “as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become.” Shapiro does precisely what Noam Chomsky notes is commonly done with Smith, reading the Wikipedia entry (if that) rather than the texts themselves:

People read snippets of Adam Smith, the few phrases they teach in school. Everybody reads the first paragraph of The Wealth of Nations where he talks about how wonderful the division of labor is. But not many people get to the point hundreds of pages later, where he says that division of labor will destroy human beings and turn people into creatures as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human being to be. And therefore in any civilized society the government is going to have to take some measures to prevent division of labor from proceeding to its limits.

He did give an argument for markets, but the argument was that under conditions of perfect liberty, markets will lead to perfect equality[...] [H]e thought that equality of condition (not just opportunity) is what you should be aiming at. It goes on and on. He gave a devastating critique of what we would call North-South policies. He was talking about England and India. He bitterly condemned the British experiments they were carrying out which were devastating India… [He also observed that] the principal architects of policy are the “merchants and manufacturers,” and they make certain that their own interests are, in his words, “most peculiarly attended to,” no matter what the effect on others, including the people of England who, he argued, suffered from their policies.

As Martha Nussbaum emphasizes in The Cosmopolitan Tradition, whenever the choice came down to siding with the workers or capitalists Smith almost invariably chose the former. This includes through taxing the luxuries of the wealthy since the “indolence and vanity of the rich is made to contribute in a very easy manner to the relief of the poor.”

Shapiro is similarly abusive toward the recently deceased Scottish-American philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre. In Chapter Three, Shapiro approves of MacIntyre’s plan for the construction of new forms of local community, adding that public virtue is “the indispensable bedrock of communal survival.” Later he claims the “entire lie of wokeness” can be explained through “what philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre termed emotivism”—the belief that “all moral judgments are nothing but expressions of preference,” or subjective taste. For Shapiro, when the “social fabric decays, emotivism becomes commonplace,” and “scavengers live on such emotivism” since it fuels the “Great Conspiracy Theory—the theory that they are only failures because they are victims.”

MacIntyre was indeed a profound critic of modernity and subjectivist ethics, and his virtue ethics deserves to be taken more seriously by the socialist left—a left he long identified with. But Shapiro completely misunderstands or resolutely refuses to acknowledge the actual breadth of MacIntyre's critique. For MacIntyre “emotivism” had become the ethical baseline for modern society in no small part because of the spread of capitalism. In his early classic Marxism and Christianity MacIntyre described Marxism as carrying on the Christian legacy of repudiating the power of Mammon and condemning the idolatry of various fetishisms. He said in 2007 that “I was and remain deeply indebted to Marx’s critique of the economic, social and cultural order of capitalism.” This was reiterated in 2016’s Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity, where MacIntyre lamented that what Marx had to teach us, we’ve had to relearn over and over again.

After all, as Shapiro himself tirelessly chimes throughout Lions and Scavengers, in a market society all value is “subjective.” Part of MacIntyre’s story is how this market ethic gradually colonized all other spheres of life, upending traditional communities and their embedded, often religious, ethics. The result was a world where we approach ethical issues with the same consumeristic approach we take to shopping—if conservative Christianity is your fashion try it on, but if not, give sexual libertinism a whirl. In a capitalist society it's not what's good that’s of value, but whatever sells that’s good. Shapiro denounces relativism in one breath and extols capitalism in the next, citing MacIntyre to prove his point, but without ever engaging with MacIntyre’s belief that there was a nexus between relativism and capitalism. Macintyre insisted late in life that he “would still like to see every rich person hanged from the nearest lamp post.” (MacIntyre would also have smirked at Shapiro’s flag-shagging nationalism. He described the nation-state as a false “repository of sacred values,” and the idea of being asked to die for the nation as “like being asked to die for the telephone company.”)

The misunderstanding is even greater with those thinkers Shapiro is criticizing. Like Douglas Murray, he heaps abuse on the late Edward Said, seeing him as a champion of a thoughtless anti-Westernism, and like Murray, he seems to be totally unacquainted with Said’s lifetime of study and appreciation of the Western canon including classical music and English literature. And the less said about Shapiro’s non-reading of Frantz Fanon, the better.

But the problems go beyond Shapiro’s misunderstandings of the thinkers he cites. The entire core of the book’s argument is rotten. While its subtitle presents it as “The Story of America,” Lions and Scavengers is not in fact a story of America, but a polemic arguing that, essentially, society’s losers deserve their fate and should stop complaining, while the rich deserve their riches. As Shapiro told Ezra Klein in a recent New York Times interview, there are those “who believe that there is an active duty in the world to make the world better, to build social fabric, to defend a civilization that is worthwhile, to innovate, to protect things that are good,” while there are “people who are basically rooted in envy and are seeking to tear down all of those things.” The second class of people, vulture-like scavengers, are simply unwilling to accept their own natural inferiority:

Individuals are equal in their rights but not in their qualities. I have the same rights that you do, but that does not mean that we each have precisely the same earning capacity. LeBron James and I have the same rights, but he is a far better basketball player than I am; meanwhile, I’d venture to say that I’ve probably read a few more books cover to cover than he has. That isn’t unjust—unless by unjust, we simply mean that we wish that God had made us all identical in every way at the outset of life. And if that’s our complaint, we ought to grow up. Anger at God for not making the world the way you want it isn’t justice. It’s arrogance, stupidity and childishness.

Just as James “did not work for his height or base athletic ability, I did not work for my inherent level of intelligence,” but the inequalities that result cannot be criticized or rectified through policy. (Yes, Shapiro did just suggest that he is to intellectual pursuits as LeBron James is to basketball, despite, as we have noted, showing clear evidence that he doesn’t read the books he writes about. Ben’s argument for his riches resulting from his superior intelligence comes in the middle of hundreds of pages demonstrating his lack of it.)

Shapiro often seems personally, even anxiously, invested in meritocratic mythologies that suggest he’s better than others. We’re reminded of Max Weber’s quip in “The Social Psychology of World Religions” that the “fortunate man is seldom satisfied with the fact of being fortunate, beyond this he needs to know that he has a right to his good fortune. He wants to be convinced he deserves it and above all that he deserves it in comparison with others. Good fortune, thus wants to be legitimate fortune.” In case there’s any doubt about whether Shapiro thinks he’s among the great “lions,” his book features a long self-applauding section in which Shapiro congratulates himself for showing entrepreneurial spirit in founding the Daily Wire, the “largest online conservative media company in the world, with hundreds of employees and millions of consumers.” Those of us who have sat through Lady Ballers may be less appreciative of the achievement. Ironically, the major contribution of the Daily Wire seems to be affirming the bottomless self-pity that has essentially become the mainstream of conservative ressentiment.

Unsurprisingly for a free-market capitalist who thinks people get what they deserve, Shapiro adopts an absolutist line on private property. He declares “private property goes to the essence of what it means to be a human being” and is “embedded in nature.” He contrasts meritorious Lions with “Looters” who typically “believe that private property is not a natural right, the result of man’s control over his own abilities[…]”

But does he give any argument for why we should believe property is a “natural right”? In fact, he waffles constantly between defending the idea by suggesting God wants property to be a natural right (good luck proving that), and defending legally enshrined property rights as useful rather than inviolable.

One of his many stabs at justifying natural and absolute property rights invokes the ideas of John Locke. Locke, “one of the great influences on the American founding, explained this right to property.” You “own the product of your hands[…] One of the fundamental principles of the philosophy of lions is that man is made in the image of God, a creative, choosing being with autonomy and power.” He then goes on to cite Locke’s argument for the labor theory of property entitlement in the Second Treatise of Government:

Though the earth, and all inferior creatures, be common to all men, yet every man has a property in his own person: this no body has any right to but himself. The labour of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever then he removes out of the state that nature hath provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property.

Locke’s labor theory of property entitlement has tempted defenders of the rich throughout history. As philosopher Elizabeth Anderson chronicles in Hijacked: How Neoliberalism Turned the Work Ethic Against Workers and How Workers Can Take It Back proponents of the “right wing work ethic” often try to paint the rich as industrious and hard working, and thereby entitled by right to property which the greedy poor aren’t entitled to. I built it, therefore I deserve it. But what Anderson notes, and Shapiro ignores, is that the theory that you should get to keep the products of your labor often leads inexorably to left-wing rather than right-wing conclusions.

First, as Matt Bruenig has long pointed out, the “labor mixing” theory of property entitlement has deep metaphysical problems. (What does it mean to “mix” one’s labor?) The far more serious defender of capitalism Robert Nozick even acknowledged this problem in his Anarchy, State and Utopia, which itself drew heavily on Locke. With no little mirth the arch-libertarian Nozick compares gaining property rights through labor mixing to pouring a can of tomato juice into the ocean in an attempt to own the sea. Shapiro also elides Locke’s own famous qualification that anyone who acquires property through their labor must leave just as much or more behind for others to use. Locke was aware that excess accumulation of property has to be balanced by a commitment to the economic common good.

But more importantly, Shapiro fails to realize what plenty of socialists recognized early on. If we do in fact “own the product of our hands,” that is a very good argument against capitalism. In the capitalist system most workers do not “own the product” of their hands. The people who prepare lattes and flip burgers don’t get to own and profit from them, nor do the people who grow the wheat for the hamburger buns or the beans for the coffee. The capitalist does. The capitalist might just own shares, without doing any actual labor themselves, yet somehow gets the profits! Migrant workers who plant seeds and pick fruit for pitiful wages should be rich as hell if Shapiro’s principles were followed. They are the real owners of what they wrought with their hands. Shapiro should logically conclude the workers are in fact being robbed by capitalists. (This was the conclusion of Ricardian socialists following Locke in the 19th century.)

In fact, Shapiro’s idea that markets reward merit is contradicted by the capitalist philosopher F.A Hayek, who Shapiro repeatedly and approvingly cites throughout Lions and Scavengers. In The Constitution of Liberty Hayek rejects the idea that market society could ever be a meritocracy. That’s because “free” markets don’t reward people for being meritorious, hard working, or even (perhaps especially) morally good. They reward market actors for gratifying the “subjective” preferences of consumers. And sometimes people get lucky enough to be born into emerald mine money, while others work their ass off day in and out while being brought up and remaining poor. It’s a lottery, not a competition of virtue. Hayek acknowledges this might seem unpalatable to those who idolize the economy as a system for rewarding people based on hard work and merit. His primary targets were people on the left who argued the worker’s hard efforts weren’t being adequately rewarded under capitalism. But the objection applies with equal or even added force to those like Shapiro who fetishize the idleness of the yacht class.

Hayek insists we need to recognize that any effort to build a true meritocracy would immensely compromise freedom since it would require massive social engineering to constantly intervene and make sure people largely succeed through choice and effort rather than arbitrary advantage. As he put it in The Constitution of Liberty:

A society in which the position of the individuals was made to correspond to human ideas of moral merit would therefore be the exact opposite of a free society. It would be a society in which people were rewarded for duty performed instead of for success, in which every move of every individual was guided by what other people thought he ought to do, and in which the individual was thus relieved of the responsibility and the risk of decision. But if nobody's knowledge is sufficient to guide all human action, there is also no human being who is competent to reward all efforts according to merit.

For Hayek and his followers, only a radically engineered society which compensates for the unfairness of life could even aspire to be a meritocracy. And we’d add, only transiently, since every time arbitrary advantage accumulated we’d have to reset. This would require radical infringements on liberty and “free” exchange. Shapiro does not reckon with this deep contradiction within his worldview: honest capitalist philosophers have recognized that meritocracy and capitalism are incompatible, rather than repeating the fable that our economy rewards merit. One can go even further back to look at the wisdom of Christian philosophers like Augustine, whose pessimistic view of human nature led him to the conclusion it was idle to assume we could ever build a society that gives people what they deserve in this life. Indeed the naivety of American conservatives is such that perhaps only they are starry-eyed enough to believe an intelligenceless invisible hand will reward people according to the Santa Claus principle writ large.

Intellectually serious people must make an effort to empathetically engage with the ideas they are criticizing, so as to ensure they understand them. That’s why, despite the agony of doing so, we have read every page of books by Shapiro. But he does not do the same, which leads him to a state of complete confusion about the motives of his enemies. For instance, he told Ezra Klein that the fundamental idea of the book came when he saw a pro-Palestine (or in his words, pro-Hamas) protest, and noticed “the groups that were protesting were people who ranged from very far left on social issues, who would certainly not agree on social issues with people who were standing for Hamas, people who were fans of Hamas, people who were just opponents of capitalism.” Shapiro asked himself what these groups had in common and concluded that they were all part of the same parasitic tendency, a bunch of scavengers who blamed society’s problems on oppressors. They are those “who produce nothing, and demand everything.”

Thus Shapiro seems incapable of even imagining the possibility that pro-Palestine protesters are motivated by a serious and honest horror at what Israel has done to Gaza. The United Nations has just released a detailed report concluding definitively that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza. Shapiro does not examine, or refute, the evidence that Palestine activists present for their positions. He doesn’t seem interested in the factual record at all. (So much for “facts don’t care about your feelings.”) He looks out on the protest, and all he sees are a bunch of scavengers trying to tear down the civilization that he and his fellow “lions” have built. When Ezra Klein asked Shapiro if he thinks Bernie Sanders is “just an enemy of Western civilization,” Shapiro replied:

Yes… I think that the easy part of all politics and all of human life is to find the places where you think that life has been unfair to people. Because life is sometimes unfair to people. The question is how you direct that. Has he directed that toward actually building better systems — or has he spent his entire career yelling at people who have become wealthy? Has he maligned them as morally inferior for having developed wealth? Has he decided that there is a class of people who are the great exploiters in his moral narrative and who must be torn to the ground?

But Bernie has directed his life toward building better systems. Medicare For All, which Bernie has been a tireless advocate of, is a better healthcare financing system. People were drawn to Bernie’s presidential campaigns not because he promised to string capitalists from lampposts (an agenda Alasdair MacIntyre might have liked), but because he offered public policies that would improve people’s lives. Shapiro does not make any effort to actually engage with the case for these policies. For him, it is enough to rant that the people who want workplace safety protections and good healthcare are simply “scavengers.”

Going back to Brandolini’s law, we could say so much more about the mountains of bullshit in this book. For instance, we could point to where Shapiro cites Karl Popper on the danger of scavengers working to “maximize their own discretionary and arbitrary power,” while ignoring Donald Trump’s draconian uses of executive power and dismissing any of the limitations on using military force imposed by international law. The entire lions-vs-scavengers framework breaks down when you think about it too much. Klein found that out when he pressed Shapiro on it, since Shapiro is a Trump supporter but Trump’s entire political appeal is based on the kind of grievances, blame, and resentment that Shapiro thinks only “scavengers” practice.

Lions and Scavengers is representative of the race to the moral and intellectual bottom that has gripped a right wing who seem to be engaged in a vast limbo contest to see how low their standards can go. It echoes far-right ideology in its framing of an existential war between strength and parasitism. It is a remarkably pretentious book that banalizes complex ideas to avoid reflecting upon them, which makes the endlessly inflated rhetoric about “lions” seem even more absurd. To invoke Nietzsche, the problem with Shapiro’s dives into philosophy and spirituality aren’t just that they fail to be deep. It’s that they aren’t even superficial.