Don’t Let Them Erase Jamal Khashoggi

We must fight to preserve the memory of a dissident killed for questioning the United States’ favorite dictatorship. Two American presidents have shamefully tried to move on.

Saudi Arabia has been ranked one of the world’s most authoritarian regimes, and is frequently placed among the “worst of the worst” in Freedom House’s survey of political and civil rights. Amnesty International says that despite a massive global “image laundering” campaign, “the human rights situation in the Kingdom has deteriorated exponentially.” It has no national elections, and Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman (MBS) uses imprisonment, torture, and execution to quash even mild dissent against the government. People can be sentenced to death over their tweets, and women who protest being kept as chattel by men can be thrown into prison and tortured. The resulting climate of fear can result in absurdities—the Financial Times recently reported that Saudi engineers and designers have been too afraid to tell MBS that his ludicrous plan for a utopian city is literally physically impossible.

No country that values freedom, democracy, and basic human rights should want anything to do with the Saudi government. Yet over the last quarter century, American presidential administrations (Bush, Obama, Trump, Biden, Trump) have warmly embraced the repressive Saudi state, helping to ensure that there is no meaningful pressure on it to reform, and no punishment for torturing and killing dissidents. This shameful American posture means that blood is on our hands, including that of Washington Post columnist and dissident Jamal Khashoggi, extrajudicially executed by the Saudi regime in 2018.

Khashoggi was lured to the Saudi embassy in Istanbul, where he was strangled and dismembered by a team of special operatives that reported directly to the Crown Prince. U.S. intelligence quickly concluded that there was no way that the killing could have occurred without MBS’s instruction, in part because in an absolute monarchy, the killing of a prominent dissident would only occur with authorization from the top.

The killing of Khashoggi was so lurid, and he possessed such social status in the United States, that the murder actually became a scandal. But he’s far from the only victim. In fact, the Saudi regime executes people routinely. The killings reached a new height last year, with 345 people being put to death, usually by beheading. Human Rights Watch warns that there have been “a terrifying number of executions in 2025” as well, including the killing of Turki al-Jasser, a journalist who “exposed corruption and human rights abuse linked to the Saudi royal family.” Al-Jasser was accused of “terrorism,” the go-to smear of state propagandists looking to demonize their political opponents. Most of those killed by the Saudi state are foreign nationals, with the most common offense being nonviolent drug crimes. Khashoggi is also not the only dissident the Saudi state has kidnapped abroad, with even princes being captured, brought back to the country, and disappeared if they get out of line. (I have only touched on the misdeeds of the Saudi state, which also include sabotaging climate talks to protect the monarchy’s right to get rich off the destruction of the planet, and horrific war crimes in Yemen.)

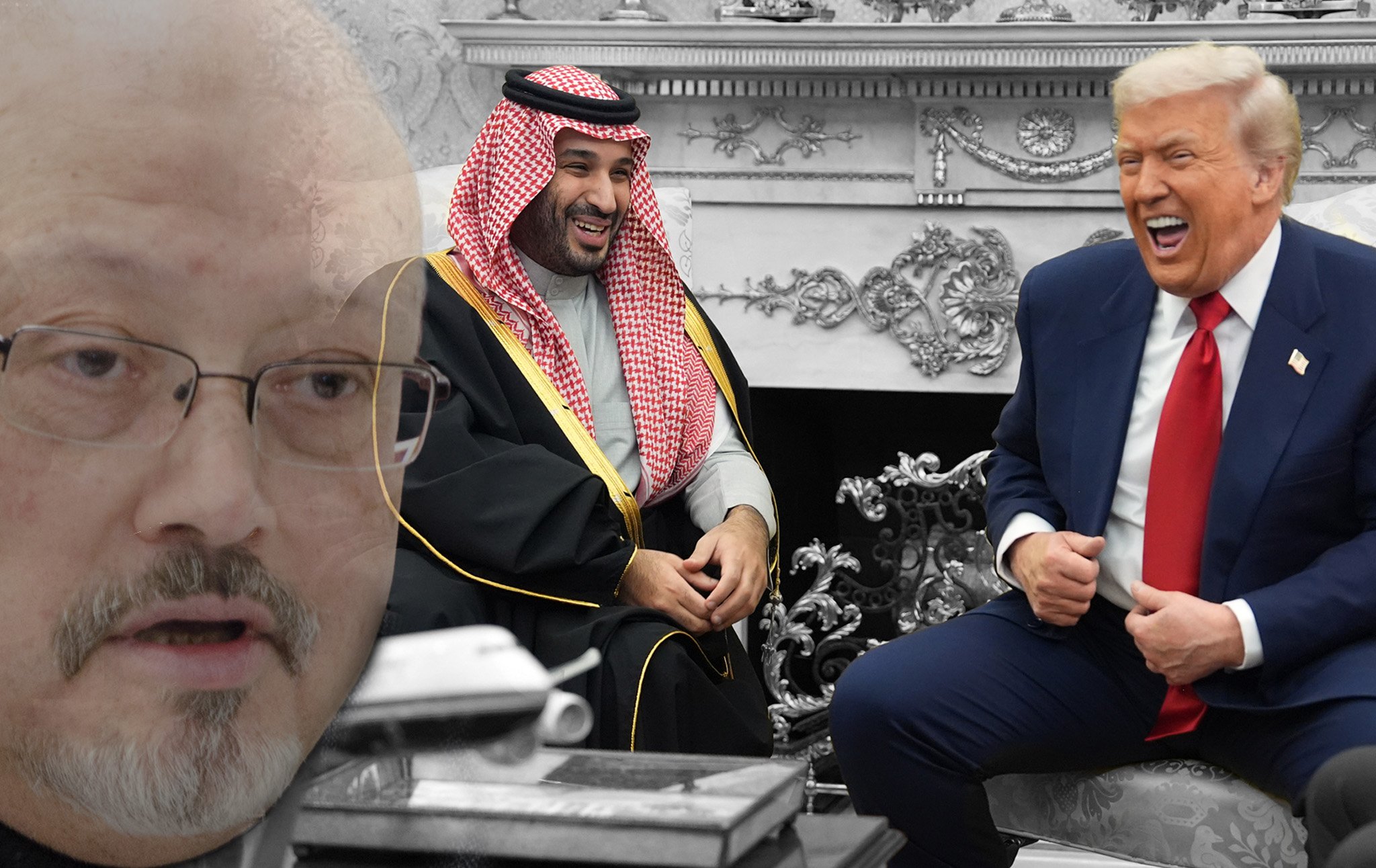

Saudi Arabia should be an international pariah. The United States, certainly, should totally cut off relations with any country that murders our newspaper columnists in cold blood—although it also shouldn’t matter morally whether an executed dissident does or does not possess a tie to the Washington Post. And yet MBS recently received a warm welcome from Donald Trump at the White House. Asked directly about the killing of Khashoggi, Trump waved away the murder, choosing to smear Khashoggi as someone “a lot of people didn’t like” who was “extremely controversial.” “Things happen,” Trump said, but MBS “knew nothing about it.”

Trump’s comments were heinous. He has long boasted that he protected MBS’s reputation after the Khashoggi killing and helped shield the Saudi leader from accountability. It will surprise nobody that Trump cares far more about business deals than about human rights, but it was still a little shocking to see the president deny MBS’s guilt when his own intelligence agencies had confirmed that MBS ordered the killing, and to see a principled dissident slandered after his death.

Still, we shouldn’t single out Trump for sole blame here. Joe Biden did almost as much to help ensure that the killing of Khashoggi wouldn’t be a lasting stain on the Saudi regime. It was Biden who decided not to punish MBS for the murder with sanctions or a travel ban, and Biden who successfully pushed a U.S. court to dismiss a lawsuit against MBS over the killing. It was Biden who, having previously called MBS a “pariah,” went and fist-bumped him, an image that the Saudi government proudly shared. Of course, it didn’t begin with Biden, either. It was Barack Obama who agreed to provide the Saudi government with $115 billion in weapons, and the Bush family had extensive, friendly ties to the Saudi royal family.

There are real consequences to this chumminess. Human rights campaigner Josh Cooper explained to Middle East Eye that the record level of executions would be unthinkable without the rehabilitation of MBS by world leaders. It’s quite simple: the fewer consequences there are for MBS’s abuses of human rights, the more Saudi dissidents will suffer. If the U.S. president sets clear standards for allies (freedom of the press, freedom of political speech, basic elections, due process), then a country wanting to do business with the U.S. will have no choice but to improve internally. If, on the other hand, the U.S. president makes it clear that who dictators kill is simply their own business, we can expect to see the repression escalate.

Others bear responsibility as well. Top U.S. comedians recently traveled to Riyadh for a comedy festival, agreeing not to criticize the regime in return for huge paychecks. U.S. media often covers the regime warmly. CNN accepts sponsored content from Saudi Arabia. There are constant articles about MBS as a “modernizer” and “reformer,” with the Khashoggi killing a mere unfortunate blot on his record. See this recent piece in the New York Times, for instance, which calls MBS “a prince with a new set of priorities.” While admitting that “the human rights picture today is still far from perfect” (I’ll say!), the writer praises MBS for “diversification of the Saudi economy, large-scale investments in renewable energy, the welcoming of foreign tourists of any faith and a head-spinning explosion of culture and popular entertainment that includes concerts, movies and art exhibitions in a country where much of that was only recently illegal.” I am sure Manahel al-Otaibi, the fitness influencer being abused in a Saudi prison for advocating women’s rights, will be greatly encouraged to hear about the new concerts and art exhibitions showcasing a new Saudi Arabia. (Note also the Times’ mention of “investments in renewable energy” without mentioning the country’s destructive role in global climate policy. Astonishingly, the writer instead says that MBS “won’t stop looking for ways to safeguard his country’s security and its transition away from oil.”)

Or consider this recently disgraceful piece from Semafor, which argues that we are guilty of judging MBS on too short of a time scale:

There’s a recurring trap in how we analyze Saudi Arabia’s monarchs: focusing on too narrow a timeframe. Nowhere is that clearer than in the debate over Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The murder of columnist Jamal Khashoggi will likely follow him forever in the Western press, as was evident during his Washington visit last week. But that’s not the metric by which his subjects will judge a reign that could stretch across half a century.

Journalists tend to like tidy narratives, and early impressions often stick. When his father became king in 2015, Prince Mohammed was portrayed as impulsive — launching a war in Yemen, dragging the country into tiffs with Canada and Germany, and famously cracking down on fellow princes and billionaires. For most Saudis, however, that turbulent stretch also included a reshaping of daily life: new jobs, expanded social freedoms, and an economy increasingly wired into global capital and poised to become the world’s biggest construction market.

By the time the first biographies of the prince rolled out, he was already on a new path. Today, he has pursued rapprochement with Iran, mediated between Russia and Ukraine, and is acting as a stabilizing influence in Sudan and Syria. Now at 40, he’s presenting himself — as The New York Times noted after his joint appearance with US President Donald Trump — as an experienced, measured statesman.

So how should we judge monarchs who will outlast most other leaders (and lowly journalists such as myself)? We will have to weigh decisions made over a few days, or even months, against the context of an 18,000-day reign. Not because we like to, but because it’s the way it is.

The writer suggests that while the “Western press” may judge MBS for the murder of Khashoggi, his “subjects” judge him differently. But wait: aren’t the country’s imprisoned dissidents subjects, too? Do their opinions not count? Do they really think the fact that the economy is “increasingly wired into global capital” is more important than the fact they are ruled by a homicidal tyrant?

Yet again, we see the total inconsistency in the way human rights abusers around the world are spoken of in the U.S. While Nicolás Maduro’s repression (not nearly as brutal as the Saudi state) is used as a potential justification for invading the country and deposing him, Saudi Arabia’s crimes are largely ignored, its executed dissidents’ names unknown unless they are of particularly high social standing in the U.S. The possibility of cutting ties with Saudi Arabia, let alone conducting a regime change operation, is never seriously discussed. If a country’s government offers us what we want, they can do what they like. If they are a rival, suddenly their crimes become moral outrages.

Since there are so many who will, out of convenience and self-interest, try to forget Jamal Khashoggi and the other brave Saudi dissidents who have risked their freedom and their lives to try to liberate their country from autocratic rule, perhaps I should conclude by quoting Khashoggi himself, who in 2017 exposed the myth of MBS the modernizer as the public relations sham that it is. Instead of reading Semafor and the New York Times, or joining with the president in treating dictatorial governance as a non-issue, we should instead listen to one of Saudi Arabia’s most principled citizens:

When I speak of the fear, intimidation, arrests and public shaming of intellectuals and religious leaders who dare to speak their minds, and then I tell you that I’m from Saudi Arabia, are you surprised? With young Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s rise to power, he promised an embrace of social and economic reform. He spoke of making our country more open and tolerant and promised that he would address the things that hold back our progress, such as the ban on women driving. But all I see now is the recent wave of arrests. Last week, about 30 people were reportedly rounded up by authorities, ahead of the crown prince’s ascension to the throne. Some of the arrested are good friends of mine, and the effort represents the public shaming of intellectuals and religious leaders who dare to express opinions contrary to those of my country’s leadership.[…]

It was painful for me several years ago when several friends were arrested. I said nothing. I didn’t want to lose my job or my freedom. I worried about my family. I have made a different choice now. I have left my home, my family and my job, and I am raising my voice. To do otherwise would betray those who languish in prison. I can speak when so many cannot. I want you to know that Saudi Arabia has not always been as it is now. We Saudis deserve better.