How the U.S. Manufactured “Christian Genocide” Claims to Attack Nigeria

The Trump administration claims to care about human rights, but its aggression in Nigeria is really about guns, gold, and imperialism.

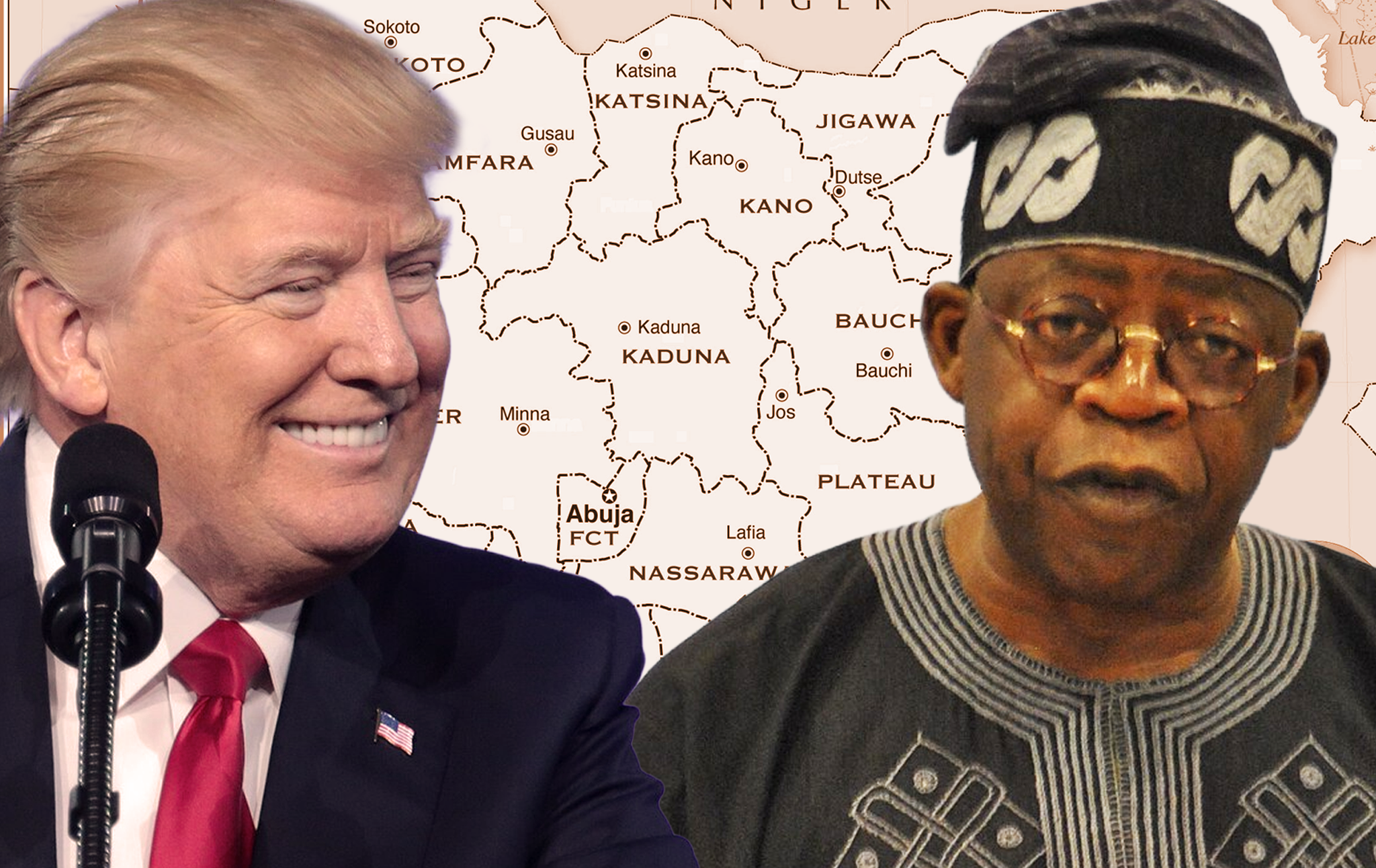

In late November 2025, President Donald Trump threatened Nigeria with a U.S. military intervention, posting on Truth Social that he would consider going “guns-a-blazing” into “that now disgraced country” if “the Nigerian Government continues to allow the killing of Christians.” The post immediately went viral in the United States conservative media space, reinforcing a narrative about “Christian genocide” that has circulated for several years. However, just weeks after that, Nigerian National Security Advisor Nuhu Ribadu sent out a post that sharply contrasted Trump’s inflammatory one, welcoming top U.S. officials, not as saviors or the leaders of the international community, but as partners in a “mature, based-on-trust relationship” with Nigeria. This is a clear example of the two extremes in how to address the complex issue of Nigeria’s growing instability. One extreme is to manufacture a crisis that requires an international response, while the other extreme is to respect Nigeria’s right to self-governance.

The so-called “Christian genocide” is a manufactured crisis, one where the language of human rights is being used as a weapon. Trump is cynically using his supposed concern for Christians in Nigeria to attack the country itself and reinforce the security frameworks of empire. In doing so, he demonstrates how artificial moral panics can be deployed as a geopolitical tool.

It’s true that Nigeria has experienced unprecedented levels of violence in recent years. There are various militant groups operating in Nigeria calling themselves bandits, jihadis (including the notorious Boko Haram), Indigenous Peoples of Biafra (IPOB), Niger Delta Avengers (NDA), and other names, all seeking to exploit the current instability in the country for their own goals. These groups have been responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of people and displaced millions, severely affecting large swaths of Nigeria. Many farmers are being killed, churches and mosques are being burned down, and villages are completely disappearing.

However, to claim that the issues of violence in Nigeria represent a genocide of Christian citizens specifically is not only inaccurate, but dangerous. Focusing exclusively on Christians in this way represents a form of denial of the suffering of Muslim populations who experience attacks at the same frequency if not more than Christians, and a refusal to acknowledge the true cause of the violence: the struggle for control of land, water, and mineral resources.

How the Genocide Narrative Works and Who Benefits

Nigeria’s “Christian Genocide” myth is well-worn, and dates back to at least 2020, when outgoing U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared Nigeria a “Country of Particular Concern” for what he called its “systematic, ongoing, egregious violations of religious freedom.” Explaining his reasoning the following year, Pompeo spoke to a number of conservative Christian leaders in Washington, D.C. and said: “I’m eager to engage in this work with them as we seek to put a stop to these ongoing tragedies.” His comments rapidly spread through the internet. As a result, numerous evangelical Christian news agencies created headlines of great urgency regarding his statements. Similar language was used by many members of Congress over the next few years, including Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri and Representative Chris Smith of New Jersey, both in speeches and official resolutions. In a very short period of time, the idea that the government of Nigeria was involved in, or at least condoned, a systematic attempt to kill all Christians in their country appeared on Fox News and in campaign stump speeches.

Last year, Senator Ted Cruz said that “Christians are being mass murdered in Nigeria” and called for sanctions to be put on Nigerian leaders who he believes have been “acquiescing, turning a blind eye” to the violence. Likewise, Secretary of State Marco Rubio has condemned what he called “mass killings and violence against Christians” and announced new visa restrictions on Nigeria in response. When making statements like this, it is common to focus solely on the attacks on churches and ignore the fact that many of the same armed groups have also been attacking Muslims, mosques, and other religiously neutral areas as well.

Statistics are also selectively used to support claims of “Christian genocide.” For example, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) reports that roughly 21,000 civilians were killed in Nigeria since 2020, through “abductions, attacks, sexual violence and the use of explosives.” However, when looking at cases where “victims’ religious identity” can actually be confirmed as a motive, ACLED’s independent monitors have found that more Muslims than Christians have been killed in sectarian violence in Nigeria’s middle belt: 417 deaths compared to 317.

In 2025, the HumAngle Foundation released a report using ACLED data, showing that it has been collecting, coding and analyzing reports of political violence and protests in Nigeria from 2020-2024, a period marked by many violent incidents. Only about 4.3 percent of those incidents occurred at places of religious worship, whereas the majority occurred at farms, markets and mining locations. However, very few of the findings by these organizations appear as evidence in the accounts given by U.S. politicians or evangelical organizations, which seem to rely on sensationalism rather than factually-based reporting.

In general terms, the numbers used by U.S. politicians to claim “Christian genocide” are primarily based on reports from the Nigerian NGO International Society for Civil Liberties and Rule of Law (InterSociety). For example, Representative Riley Moore of West Virginia recently cited the organization’s estimate that “over 7,000 Christians have been killed in Nigeria in 2025 alone.” But a BBC investigation has found that InterSociety’s methods are completely untransparent. InterSociety often cites media reports that don’t specify victims’ religions and then assumes they are “Christian” due to their own unverifiable analysis. Upon tallying the death tolls cited in InterSociety’s own source lists for 2025, the BBC found that the sums reported were less than one-half of the 7,000 the group had claimed, and that “some of the attacks also appear to be reported more than once.” Once the inflated totals are passed through the U.S. political system via campaign activity, the disputed claim is transformed into the established fact upon which the perpetual motion machine of moral indignation is sustained.

In these narratives, the Nigerian state is portrayed as monolithic and evil with no regard to the fact that among the past presidents of Nigeria, four of them have been Christians. As Zikeyi John writes for The Cable, the country has long had an “unwritten understanding that power should rotate between the north and south and between Muslim and Christian to breed inclusiveness and cohesion.” In addition, Christians still hold the majority of top positions within the State, including the current President of the Senate, Sen. Godswill Akpabio, and the Minister of Defence of Nigeria, General Christopher Gwabin Musa. Moreover, the state’s military has lost thousands of soldiers regardless of religion fighting the very militant groups accused of perpetrating the “Christian genocide.”

As Mahmood Mamdani has argued, human rights language is never politically neutral. In many cases, it is used by powerful foreign governments to delegitimize a sovereign state in the name of moral outrage. The “Christian Genocide” label, as well as the Nigerian military’s actions, fit into this exact model, and are being used, not as a call for justice, but as a strategic pretext for intervention in order to gain control over Nigeria’s natural resources.

One of the people calling loudly for foreign intervention in Nigeria is the American mercenary leader Erik Prince, formerly of the infamous Blackwater corporation, and now CEO of Vectus Global. In an interview with the Australian Spectator magazine, Prince said “tens of thousands” of Christians were being killed, and that a corrupt Nigerian government was doing nothing about it, but that “the private sector can actually help put that fire out.” On another occasion, he urged the Pope to “fund my colleagues to protect Nigerian Christians from the marauding Muslims who are slaughtering them.” Prince has close ties to Donald Trump, since his sister Betsy DeVos once served as Trump’s Secretary of Education, and he is quite clear about his goals of aggression in Africa, saying that the United States should “just put the imperial hat back on, to say, we’re going to govern those countries,” since “pretty much all of Africa, they’re incapable of governing themselves.” In this way, Prince is a perfect example of the kind of person who finds the “Christian genocide” narrative useful.

This use of the “Christian genocide” framework is not merely incorrect on a historical basis, but is an example of what scholar and author Samar Al-Bulushi calls “war-making as world-making.” In Al-Bulushi’s recent book of the same name, he explains how U.S. leaders used counter-terrorism efforts against Al-Shabaab in Kenya to gain greater influence over the country and its politics, redefining Kenya as a chaotic place needing outside help. In the same way, U.S. leaders today are attempting to create a new geopolitical identity of Nigeria—one that must implement U.S.-backed security protocols, introduce foreign contracted groups, and interpret local communal disputes over land rights as religious terrorism which would give an opportunity for external actors to exercise control over Nigeria’s internal conflicts.

In 2025, the International Journal of Research and Methodology in Politics analyzed how this was happening. There, scholars found that Donald Trump in particular had “elevated localized violence into a global moral crisis” through his rhetoric, promoting “securitization” in order to justify “extraordinary measures beyond normal political procedures, including emergency laws, intensified policing or even foreign intervention.” In fact, Trump has actually carried out such interventions, launching airstrikes against what he claimed were “Islamic militants” in the Sokoto region on Christmas Day 2025 and threatening more strikes “if they continue to kill Christians.” However, the journal also found that Nigeria’s local media, civil society, and religious leaders have continuously criticized the U.S. definition of the violence as “genocide” due to the fact that they believe the U.S. is misinterpreting the realities of their own country.

The Gold, Guns, and Geopolitical Aspects of “Genocide”

There is an abundance of information on gold and minerals in northern Nigeria in a variety of geologic literature and commercial trade literature, as there has been for decades. Some of the states in this region include Zamfara, Kaduna, Niger, and Kebbi State, which contain one of the largest gold belts in the world yet to be developed. Artisanal and small-scale mining operators make up approximately 80-85 percent of all mining operations in Nigeria, and a very large portion of these mined minerals are being smuggled out of Nigeria; UN Comtrade statistics from 2012 to 2018 indicate that approximately 97 tons of gold valued at over $3 billion was exported from Nigeria illegally during those six years. These illegal exports not only deny the Nigerian government the opportunity to generate income through taxes on the minerals, but they also fuel and support armed bandits, criminal organizations, and create instability within communities throughout Nigeria.

Thus, it’s highly deceptive to emphasize the religious aspect of the violence in Nigeria while staying silent about the economy. The U.S. politicians who declare “the killing of Christians” do not mention that approximately 70 percent of the artisanal gold mines in Nigeria are owned and operated by Christian communities in the middle belt, and are currently being taken by heavily armed groups using arms that were supplied through Libyan stockpiles, many of which became available after the U.S.-led NATO coalition overthrew Libya’s government in 2011. The politicians also do not point out that there are Chinese and Emirati companies competing to build processing facilities adjacent to the above-mentioned sites, with or without the knowledge and permission of the local elites and the government, and as such, may be complicit in the chaos caused by the fighting. In particular, one 2024 study found that the United Arab Emirates, a close ally of the United States, is “the destination [of] choice for conflict and smuggled gold” from Africa.

Nigeria’s government itself has supported the emergence of this scenario, however not due to malevolent intent, but rather through elite complicity. Unable to rely on the national government, a number of Northern and Southern Governors have established Community Watch Corps, recruiting local communities with or without obtaining Federal authorization. As such, they have created a dual chain of commands for their respective areas of jurisdiction, circumventing the Nigerian military.

The truth is this is not a holy war based upon religion, but rather an open fight for land within a post-oil economy in which land is equal to lithium, water is equal to power, and gold is equal to survival. Calling this situation a religious genocide will only result in further loss of life, because it will conceal the parties profiting from violence, those who supply weapons to all sides, and how true peace can be achieved.

Coalition for Dialogue on Africa (CoDA)

At a time when there are many using misinformation to cause public outcry, one group's perspective is vastly different from nearly all others: the Coalition for Dialogue on Africa (CoDa), a pan-African policy forum established by former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo. In contrast to Western think tanks that generally go into a location with preconceived notions and agendas, CoDa incorporates traditional leaders, religious leaders, youth organizations, and other community peacebuilders from conflict-ridden parts of Nigeria—not to simply state religion as the cause of violence, but to understand what the causes of violence were in each of those communities.

CoDa held several private discussions in 2025 with various stakeholder groups in Kaduna State, Plateau State and Benue State. These three states contain many of the areas where agricultural conflict between herders and farmers, conflict related to mining, and other forms of violence have been misinterpreted as being an Islamic vs. Christian war. Through these meetings, CoDa identified four primary factors that contributed to most of the conflict in all three states: land rights disputes, climate-related shortages of natural resources, illegal weapons entering the region, and the breakdown of local government systems. In other words, religion was being used mainly to identify which side of the conflict people belonged to, and not as justification for violence.

Instead of issuing press releases calling for U.S. military involvement, CoDA worked with states to develop and restore community-based early warning systems, developed and advocated for inter-faith grazing agreements, and worked to reform the way security personnel work in rural Nigeria. CoDA's advocacy in Plateau State resulted in the establishment of a joint farmer or herder committee that produced a significant reduction in violence against farmers and herders, within one year, with no foreign drones or battalions involved.

What allows CoDA to be successful, and why CoDA is ignored by the Western media, is CoDA’s refusal to play the victim role. It represents a group of complex individuals working to manage a broken system, and provides no easy, obvious villains for U.S. audiences to rally behind. Instead, CoDA views Nigerian people as being able to create their own peace.

African Courts, Media, and Faith Leaders Are Calling Out the Lie

Nigerians have been documenting, examining, and contesting violence within Nigeria long before Western commentators identified Nigeria as a genocide zone. The Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP), based in Abuja, Nigeria, has filed numerous lawsuits against various Nigerian state governments, along with the Minister of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) Abuja, Mr Nyesom Wike, for failing to provide protection to all of its citizens, both Christians and Muslims, from banditry and militia attacks. All of the legal actions taken by SERAP are based upon the constitutional rights of all citizens under the law, and not upon the religious identification of victims of violence.

Likewise, many Nigerian media outlets (including The Cable, Premium Times, and BBC Pidgin) have used data-based research to show that many victims of communal violence within the states of Taraba, Kaduna, and Plateau are simply poor and rural-dwelling individuals regardless of religion.

In December 2025, the Nigerian government signed a $9 million lobbying deal with the Washington based D.C.I. group as an effort to protect the international image of Nigeria, and to inform the United States administration of their efforts to protect Christians in the country. The reason for this expensive defensive lobbying is because the same form of Washington-based policy advocacy has been successful in gaining momentum for the opposite narrative, resulting in the designation of Nigeria as a “Country of Particular Concern” (CPC). This was based almost solely on reports from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), a federal agency which has received renewed attention in recent years.

In 2017, USCIRF began a campaign to have Nigeria be designated as a “country of particular concern” for religious persecution, under pressure from evangelical Christians within the commission. The designation of a country as a “country of particular concern” can lead to serious consequences, including sanctions that allow humanitarian intervention by foreign nations.

Despite their influence, however, the USCIRF is a Washington-based agency which has conducted no on-the ground research in Nigeria and does not even maintain an office within the country. But their message mirrors much of that of evangelical organizations such as the Family Research Council and Open Doors USA, organizations that have advocated for the use of military force in Africa for decades under the banner of religious liberty. When the U.S. Department of State did not label Nigeria as a “Country of Particular Concern” in 2020, a status that remained in place during the administration of President Joe Biden, the aforementioned organizations did not reduce their efforts, but increased them by circulating petitions and op-eds that failed to recognize Nigeria’s Christian-led security forces and peace building initiatives.

Meanwhile, even many religious institutions in Nigeria which are typically perceived as being divided by their religious identities are fighting back against this politicization of religious identity. In 2023 the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) and the Nigeria Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs (NSCIA) issued a joint statement calling for unity to deter foreign actors from using religion as an element for their political manipulation on the people of Nigeria.” Bishop Timothy Cheren in Abuja has made serious warning about how the “narrative of genocide” plays into the hands of those who seek to use division as a means to generate wealth. In similar fashion, the Sultan of Sokoto, Muhammad Sa’ad Abubakar, the religious leader of Nigerian Muslims, has emphasized that bandits are without a religion and urged the people to concentrate on their pursuit of justice rather than blaming.

Perhaps the most powerful rejection of this framework is that it is rejected by survivors themselves. Recently Kaduna State Governor Sen. Dr. Uba Sani provided humanitarian support to 450 widows in Southern Kaduna from both Christian and Muslim communities, where some of the windows spoke about their husbands being killed by armed gangs—yet none of them called for foreign involvement. Rather than call for outside help, they called for functional police stations, equitable land courts, and an end to the illicit sale of weapons.

These voices are not anomalies. Rather, they reflect an overwhelming consensus of people in Nigeria living through this conflict on a daily basis. The violence is due to a failure of government, not a holy war. However, their views have been systematically removed from U.S. discourse for the simple reason that their views do not serve the interests of those benefiting from chaos. When a U.S. senator like Ted Cruz cites one church attack to support his claim of genocide, he has removed the Muslim woman and her four children that were butchered and killed on the road, in broad daylight in the same district, the day before. When a lobbying firm claims Zamfara is a hotbed of Christian persecution, they ignore the fact that the state’s gold mines are currently being fought over by rival militias, with some of the militias being led by Christians and others being led by Muslims, all of which are funded by shadowy networks.

The erasure of Nigeria’s violence is political because it gives Washington a platform to act like a moral authority while ignoring their own role in creating a lot of the chaos, with weapons, behind-the-scenes security arrangements, and international pressure which weakens the Nigerian government. However, the Nigerians are not waiting for Washington to give them permission to create peace. The movement to recognize the Nigerian state's role in preventing religious persecution has gone beyond courtrooms into villages; it has made it clear that we are not icons in your culture wars, we are individuals who want to obtain justice based on our own terms, and that is more important than any manufactured crises that will upset the established order.

Think about it like this: as U.S. government officials claim that Nigeria fails to provide protection for its Christian citizens, U.S. corporations have been openly expanding their presence into northern Nigeria where there is an abundance of minerals. The Deputy Chief of the political-economic section of the U.S. Mission, Kenise Hill, identified Nigeria as a “critical mineral partner” in recent years. At the same time that the U.S. identified Nigeria as such, the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) are supporting private-sector projects that align with U.S. strategic interests, including infrastructure, regulatory reforms, and clean-energy investments in some northern parts of Nigeria, which have been designated as potential genocide hotspots with a “worsening security situation.” In addition, through the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM), the U.S. supplies advanced security equipment and training services to some of Nigeria’s state governments through Nigeria’s federal government.

Does all of this seem like a coincidence? No. It appears that the playbook is very well defined: create the appearance of an international crisis or humanitarian emergency; delegitimize the sovereign host government; then, enter the fray as the savior, with the requisite contracts in hand.

Why This Matters Beyond Nigeria

The myth of a Christian genocide can be dangerous in its own right because while it is not true, it follows a colonialist model we have all witnessed in Congo, Iraq, Libya, Venezuela, and so on. When western powers claim a country south of their borders is either too corrupt, or too broken, or too savage, to self-govern, they do not send missionaries. Instead, they send corporate extractors of resources, mercenaries, and political operatives. Thus, the language of human rights can serve as a justification for economic exploitation.

The only way this can occur is through the separation of human rights language from the historical context that defines it; an approach that scholars such as Mahmood Mamdani have long argued is a method to decrease the sovereign capacity of Africans, under the guise of being their protector.

However, groups such as CoDa and SERAP show that grassroots, secular peace building can work if given room to grow. For peacebuilders, journalists, advocates, and policymakers there is a lesson here: do not outsource your moral authority to Washington. A Nigerian’s life should not be a trade-off in a U.S. political debate.

Rather than hyping sensationalized claims made from a distance, support analysis generated by Africans themselves. Fund local media outlets. Ask yourself who profits when a conflict that is extremely difficult to understand is summarized in a single hashtag. And do not forget that it is the people who are directly impacted by violence in Nigeria who do not want foreign troops on their soil. Instead, they want functioning courts, justly written land laws, and an end to the constant flow of arms, regardless of where they originate.

The real genocide is being carried out in the slow, systematic elimination of African leadership, one manufactured crisis at a time.