The True Story of the Rwandan Genocide

In her new book “Do Not Disturb,” Michela Wrong explores why the west was so eager to believe lies about the Rwandan genocide.

History is rarely made of events. Though terrorist attacks, riots, elections, and declarations of war give it form, in hindsight they are more often signposts along the trail of human experience than the trail itself. But even when a certain event is only marginally important in the grander scheme of things, it can still reveal historical truths that were obscure for years or decades until then.

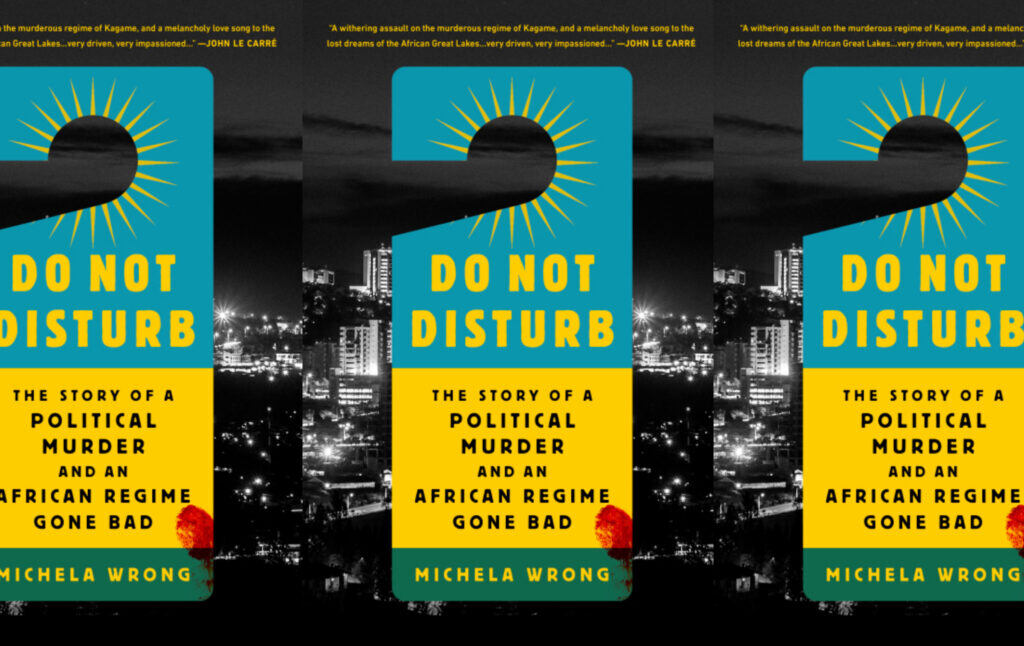

In veteran Africa correspondent Michela Wrong’s new book, Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad, the event in question is the 2013 assassination of Patrick Karegeya, once Rwanda’s chief of intelligence and one of the country’s most prominent citizens. But the larger and more vivid backstory is about how a regime so often hailed as a “model state”—not just for Africa, but for the entire world—has lost any claim to the moral high ground nearly two decades after emerging as the savior of a people reeling from the aftermath of a genocide.

In 2013, Karegeya was living in guarded exile in South Africa. Though he had long been among Rwanda’s most vocal boosters in the international press, in recent years he had turned against the country’s entrenched ruling party, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). Always careful about who he met and how, on New Year’s Eve he dropped his guard to meet a friend from the home country in an upscale Johannesburg hotel. The next morning, hotel employees found the old spymaster strangled to death. As investigators later described it, the scene bore the marks of a Mossad-like professional hit. After Karegeya’s friend lured him upstairs, the killers seemed to have strangled him on the bed to muffle the sounds of his kicking heels, then tossed a duvet over his corpse to make any casual visitor think the victim was merely sleeping. As a final touch, the killers hung the room’s “Do Not Disturb” sign from the door handle, keeping any hotel employee at bay while they slipped off into the night.

The RPF immediately denied involvement. But Rwandan expatriates and scholars of the country around the world knew instinctively who had killed Karegeya—and why they’d done it. Speaking in the local language not long after the murder, Paul Kagame, Rwanda’s sole president since 1994, confirmed their suspicions with a characteristic mix of ambiguity and bravado. “Whoever is against our country will never escape our wrath,” he said. “The person will face consequences. Even those who are still alive, they will face them.”

How could a president—any president, but especially one so generously supported by the United Nations, western governments, and philanthropist celebrities from Bono to Bill Gates, Bill Clinton to Howard Buffet—be so bold as to almost expressly confess to a murder before the world? The question sears the consciences of many Rwanda defenders, including Wrong, who for much of her life as a journalist counted herself among a legion of foreign apologists.

“My career had taken me elsewhere, Rwanda was no longer my beat,” she says of her reaction when catching up on the RPF’s growing list of abuses up to and including the Karegeya murder. “Still, it was painful to accept that I may have unwittingly misled my readers.”

To tell almost any story about Rwanda today, it’s necessary to devote some space to the event that has defined it in the eyes of the world. Over 100 days in 1994, members of the majority Hutu ethnic group murdered some 500,000 to 600,000 members of the minority Tutsis in what’s universally acknowledged as one of the worst atrocities of the 20th century. For the anglophone west, the genocide marked the beginning of a long encounter with Rwanda, but it was a messy place to start. Often recounted as a singular moment, a sort of spontaneous combustion on a national scale, the genocide was only the most horrific stage of a long simmering, low-intensity war in which the distinction between victims and aggressors was rarely clear. Foreign journalists were either unaware of the backstory or unable to fit it into the slender space their outlets reserved for Africa coverage, by then already consumed by South Africa’s apartheid-ending elections earlier that year. Instead, they described the calamity with an historical vocabulary already familiar to European and American audiences.

So the Rwandan genocide became an African Holocaust, with the Tutsis cast in the role of the Jews, the Hutus their Nazi oppressors, and Paul Kagame “a mixture of Franklin Roosevelt, General Eisenhower, and George Patton,” in the words of the eminent historian of the region Gérard Prunier. It was a role the RPF was all too willing to take: if they were the victims of an African Shoah, post-genocide Rwanda could be the continent’s new Israel. When western embassies flew RPF leaders to the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem to see how that country honored the genocide central to its founding, Rwanda’s new regime took the symbolism of triumph over victimhood to heart. “Museums set officially approved narratives in concrete,” Wrong says. “As the cement solidifies, counternarratives, complexities, and nuances get lost, usually deliberately.”

Among other stories lost were those of the RPF and its longstanding leader. Rwanda is a small and densely populated country—around 13 million people inhabit an area slightly smaller than Massachusetts—and the ruling clique which Kagame leads (and to which Karegeya once belonged) is just as concentrated. Wrong quotes a number of dissidents who were close enough to both men to know their hidden pasts. While the RPF was a rebel movement in exile in neighboring Uganda, Kagame found his place as a master of espionage. The role made him vital to the organization, but it also made him one of the officers most hated among the rank and file, as he spied on every soldier in search of traitors. According to one exile who knew him at the time, Kagame relished every opportunity to sentence his disgraced comrades to an unceremonious execution.

In Wrong’s telling, the RPF’s rise to power also appears less heroic than it ever has in the most widely cited western accounts. At the start of the genocide, the RPF—by then firmly under Kagame’s leadership—marched to Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, to seize power for itself. Western leaders would later praise the RPF for being the one armed group willing to intervene in the genocide. But in Wrong’s description, the RPF rarely stopped to save fellow Tutsis from the still-unfolding slaughter. By the time Kagame’s exiled troops arrived, much of the nation’s leadership was dead or on the run, and hundreds of thousands of Hutus were fleeing for neighboring Zaire (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo). As the only organized group with portable phones and cars, the RPF was uniquely positioned to take the reins of government. Guilt-ridden western governments, meanwhile, were more than willing to believe rebel leaders with a penchant for executing dissidents were ready to bring the country together.

They were not. To anyone who bothered to look at that time, signs abounded that the RPF leadership was interested in anything but reconciliation. In one harrowing episode, Wrong tells us about a team of U.N. researchers led by the legendary American consultant Robert Gersony, who visited Rwanda in August 1994 to chase down reports that RPF troops were enacting retribution against Hutus. Already adept at handling inquisitive visitors, the RPF had advised foreigners to keep to the main roads. Taking note of the suggestion, Gersony and his team drove down the nearest minor trail they could find instead. Just two hours from Kigali, in an area controlled by the RPF, the group found the bodies of more than 100 people neatly arranged in the yard of an old colonial building. They had just been murdered, ostensibly by RPF troops, mere hours or minutes before.

The Gersony team’s findings, collected from numerous accounts of such massacres carried out by RPF troops, might have shocked western leaders into turning their back on Rwanda’s new rulers. Instead, the U.N. disavowed the consultants’ work, consigning it to the world of rumors and innuendo—not unlike the allegations they had been tasked with assessing in the first place. “There were still a lot of armed Hutus on the ground and the message to them was, ‘We can murder you with impunity and the international community won’t do anything about it,’” says one team member. It was an early instance of the world covering for the RPF, and RPF leadership feeling emboldened as a result. There would be many more.

Do Not Disturb is a remarkable catalog of lies the RPF sold to western apologists and the realities they covered up. Throughout, Wrong tells us, Kagame and other RPF honchos embraced their role as the leaders of an African Israel, knowing the west would hesitate to criticize anything they claimed to do in the name of protecting the Tutsi people. From murdering Hutus in Rwanda en masse, the RPF graduated to murdering them en masse in Zaire, then overthrowing Zaire’s feeble government in 1997, conquering much of the country’s territory and selling its riches—gold, ivory, diamonds, and more—on international markets as Rwandan exports and collecting the profits for itself.

This last violation marked the last time many high-ranking officials swore allegiance to Kagame. For leaders who wanted to build a stable home for their people, seeing the RPF undermine regional security purely to enrich itself was too much hypocrisy to bear. Among those who left in dismay over the RPF’s pillage was Patrick Karegeya, who took asylum in South Africa in 2007.

And yet even now, as the RPF and its allies continue to rob its resource-rich neighbor, albeit through less conspicuous channels, western governments continue to stand with Rwanda. Why? One reason, Wrong tells us, is pure political theater. A master of playing both sides of any game, Kagame has done much to mimic the western leaders whose patronage keeps him in power. That menacing speech following Karegeya’s murder? Kagame delivered it at a National Prayer Breakfast. A version of the longstanding American conservative ritual has been an annual rite in Rwanda since 1995. Kagame has also introduced strict anti-litter laws, including a plastic bag ban, giving him the veneer of a progressive leader while simultaneously making Kigali the cleanest capital on the continent—a fact rarely missed by first-time European and American visitors. Today, a city which was once the poster image for the stereotypical 1990s African hellhole is the quintessence of politically correct “New Africa”: on the rise, overcoming adversity, and bravely charting a course for an inclusive future.

And for those not won over by shimmering skylines alone, Rwanda’s numbers also tell the tale of an African success story. 10 years after the genocide, the country was reporting economic growth of 7 percent or more, on par with China. It was more than enough to give development specialists and journalists plenty of evidence that Kagame’s declared plan to raise his people up through a fierce dedication to foreign investment was working, as if Rwanda’s growth spurt had more to do with its tech incubators than old fashioned resource plunder.

There were people who could have blown apart these and other lies with reams of evidence and insider knowledge. As government officials peddling Rwanda’s post-genocide myth onto the world, Karegeya and other high-ranking authorities had been indispensable sources to numerous western reporters. But as disillusioned turncoats eager to recant old lies, they struggled to find anyone to run their story. “Who, in Rwanda, was better placed to spill the beans on Kagame’s regime than its former head of external intelligence, ruling party secretary-general, attorney general, and army chief of staff?” Wrong asks. “Yet curiosity proved in astonishingly short supply. It was, perhaps, a case of ‘Tread softly, for you tread on my dreams.’ Rwanda’s story had the international community so thoroughly by the emotional and intellectual throat, it could not, now, wrest free.”

Reading Do Not Disturb, I wondered if perhaps the Rwandan myth was not a broader indictment of a morality based on statistics. Sure, apologists say—usually quietly, when sensing like-minded company—maybe the RPF rigs elections, bans unfriendly news outlets, and stymies opposition parties (to say nothing of assassinating prominent dissidents abroad). But Rwanda’s GDP is rising and its health metrics are improving. In poor, struggling Africa, who else but a strongman like Paul Kagame could make such a turnaround possible? If our moral goalpost says “this is wrong,” perhaps it’s time to move our moral goalpost. After all, that’s what the data tells us.

It’s the kind of argument Bill Gates—one of Rwanda’s biggest patrons—made in a 2018 interview with Ezra Klein that might have made Kagame smile. “There’s never been as strong a coupling between economic growth and democratic freedoms as we’d all like,” Gates said, going on to explain that authoritarian China and (in another era) South Korea and Taiwan had all grown much faster than democratic India ever has. “The human freedom argument is going to have to be made on its own,” he said. Human rights are good. Growth is more important.

But there’s a problem with being so concerned with outcomes over process, one even Gates should be able to appreciate: sometimes the numbers are bad. At the very least, Rwanda’s decade of rapid economic growth owes heavily to the theft and export of resources from its larger, weaker neighbor (not to mention considerable foreign aid dollars). But as Wrong tells us, a few of the handful of people qualified to reverse engineer Rwanda’s self-reported, World Bank-certified economic indicators believe the RPF is inflating even those numbers to curry favor with donor countries. One economist who only publishes on Rwanda anonymously for fear of retribution believes the country’s poverty rate has increased 15 percent since 2011—faster than any country in the world for which comparable data is available, with the exception of South Sudan. Under the myth of Rwanda’s rise is plunder, and under that crime is a bag full of accounting tricks.

Near the end of Do Not Disturb, Wrong shows us an eerie scene from Rwanda’s international affairs. In a Johannesburg courtroom, an inquest convenes to determine what, if any, responsibility the Rwandan government bears for Patrick Karegeya’s murder. But what should be a moment of reckoning for the world barely draws any of the numerous foreign reporters based around town. “I hadn’t expected any other journalist to bother flying all the way from London for the event, but I was still surprised,” Wrong says. “A local gangland stabbing would have attracted more attention.” The RPF had feared Karegeya enough to kill him, but the world still didn’t care what he had to say.