What Americans Still Don’t Know About the Vietnam War

Vietnam War veteran W.D. Ehrhart discusses how he went from eager enlistee to anti-war activist.

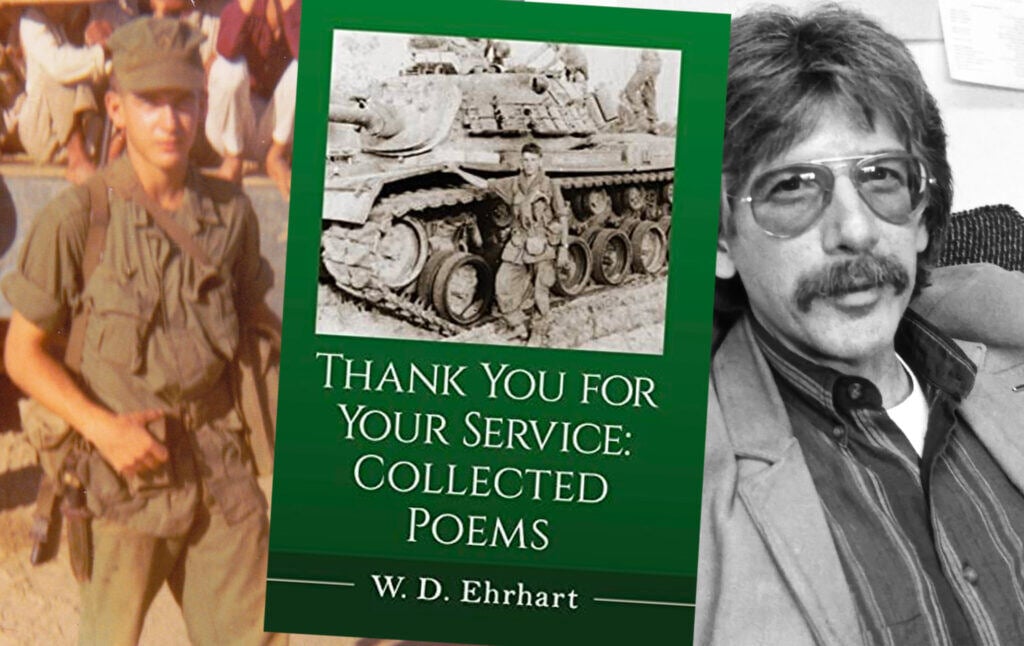

Dr. W. D. Ehrhart is an award-winning poet, scholar, and teacher of history and literature. He has worked as everything from a forklift operator to a newspaper reporter to a merchant seaman. He has written on a broad range of subjects, but a great deal of his work is informed by his experience in Vietnam in the United States Marine Corps. His collected poems have been published in the book Thank You for Your Service, and he is also the author of several memoirs about both his first-person observations of the Vietnam War and his life after returning, including his participation in the Vietnam Veterans Against the War movement. His work can be found at https://wdehrhart.com/. This interview from the Current Affairs podcast has been edited and condensed for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

I want to get us back in touch with that sense of history that, as you point out, we so very much lack in this country. Let’s start by going back to the beginning to your upbringing in a small town in Pennsylvania, where you campaigned for Barry Goldwater and waved the flag in the Memorial Day Parade and where Elvis Presley was a scandal. Paint us a picture of that time and how you felt about the country. Take us back to the time and place before Vietnam.

Ehrhart

It was good old small town America in southeastern Pennsylvania, very rural. It’s suburbia now, but back then half of my classmates in high school were farmers’ kids. The town itself had 5,000 people. My father was a Protestant minister and therefore pretty prominent in the community. I had two older brothers, and then a brother who’s somewhat younger than I am. There was almost no real poverty. And there was not anything you could call real wealth. The wealthy people lived up on Ridge Road, and they were like the hospital administrator and the lawyer and people like that. But it wasn’t the kind of wealth that we think of as people rolling in dough. People like that didn’t live in Perkasie. It was all white, very homogenous. We had about three Jewish families in town, and we thought we were really liberal. I didn’t really know a Black person. I’d met a few Black people on rare occasions, but not in Perkasie. I didn’t have a Black friend until I joined the Marine Corps. And I was 17 years old at that point.

It was also very Republican. I think my parents were actually Roosevelt Democrats, but they didn’t make a big show of it. I was born only a few years after the Second World War. Every Memorial Day, all of the fathers of my friends would get dressed up and march around on Memorial Day in their American Legion uniforms. And it was very, very traditional America.

My first memory of television was of Russian tanks in the streets of Budapest in 1956. I remember Nikita Khrushchev banging his shoe on the podium at the U.N. and shouting, “We will bury you!” I woke up one morning and the commies had built a wall right across the city of Berlin literally overnight. I lived through the Cuban Missile Crisis. So when Lyndon Johnson said, “If we do not stop the communists in Vietnam, we will one day have to fight them on the sands of Waikiki,” I had no reason to question any of that. I remember standing out on my front lawn in 1957 and watching this little white light go across the sky every 90 minutes. That was Sputnik. Now the Russians could nuke us. They had missiles. So all of this stuff created a vision of the world that was very much the Cold War mindset: We’re the good guys; they’re the bad guys. John F. Kennedy becomes president. “Ask not what your country can do for you … and we will bear any burden, pay any price.” All of that sounded great.

When Kennedy was murdered, my oldest brother and I drove down to Washington, D.C., and we stood for eight hours in freezing late November weather, totally underdressed. We stood there all night long from 10 p.m. until 6 a.m. just to walk through the Capitol Rotunda to see that closed casket. And when I walked through there, I cried. My country was the finest thing that God had ever put on Earth. It was that simple. And when I joined the Marines, for a combination of very personal reasons and truly patriotic reasons, I believed I was doing God’s work.

Robinson

In your memoir, you quote this remarkable editorial you wrote for the school newspaper right before you joined the Marines. It was about Vietnam. There were protests. You said, “There are those who say that we are fighting wars to liberate people who do not wish to be liberated. But we don’t believe that. We believe in the freedom of the Vietnamese people.” You weren’t drafted. You signed up for the Marines out of a real sense of idealism.

Ehrhart

I was 17 when I joined. I was too young to register for the draft. My parents had to sign the enlistment contract because I was not yet 18. They were not too keen about doing that—but not because they had any objections about the war. They believed the same things about America that I believed. I got my beliefs from them. You end up being a mirror of your parents and your community. So they thought—and my mother told me about this when I was well into my 20s—We have a son who can go to college but instead is going to go into the Marines in the middle of a war? What mother wants that? After a long, anguished conversation, which I do remember, I said to her, Is this the way you raised me, to let other mothers’ sons fight America’s wars? How could she answer that? That’s not the way she raised me. So she signed the papers.

When I came back a couple of years later, fucked up six ways to Sunday, I stayed that way for a long time. And I’m sure that my mother often thought that things would have been different if she hadn’t signed the papers. But the thing is, I would have spent that whole summer of 1966 making her life miserable. And I would have joined the Marines as soon as I turned 18 in September, anyway.

BEAUTIFUL WRECKAGE

by W.D. Ehrhart

What if I didn’t shoot the old lady

running away from our patrol,

or the old man in the back of the head,

or the boy in the marketplace?

Or what if the boy—but he didn’t

have a grenade, and the woman in Hue

didn’t lie in the rain in a mortar pit

with seven Marines just for food,

Gaffney didn’t get hit in the knee,

Ames didn’t die in the river, Ski

didn’t die in a medevac chopper

between Con Thien and Da Nang.

In Vietnamese, Con Thien means

place of angels. What if it really was

instead of the place of rotting sandbags,

incoming heavy artillery, rats and mud.

What if the angels were Ames and Ski,

or the lady, the man, and the boy,

and they lifted Gaffney out of the mud

and healed his shattered knee?

What if none of it happened the way I said?

Would it all be a lie?

Would the wreckage be suddenly beautiful?

Would the dead rise up and walk?

Robinson

A great deal of your writing is about how the worldview that you grew up with was shattered. Do you remember the first moment at which things began to seem strange or unexpected? Was it the brutality of training? Or when you got to Vietnam?

Ehrhart

Actually, there’s a real misconception that Marine boot camp is a brutal thing. Looking back on it now, I’m amazed at how carefully programmed it was. In Vietnam, I was placed in the intelligence section of an infantry battalion. We handled prisoners and detainees. Three days after I got there, one of the rifle companies sent in a bunch of detainees: civilians detained for questioning. There’s a whole different set of rules for how you’re supposed to handle detainees. They’re not prisoners of war who are combatants caught in the act of fighting.

So I’m supposed to replace this corporal who’s like a year older. We’re meeting these two tractors coming in. And I can see a bunch of Vietnamese on top. And as the tractors pull into the park, the Marines up on top start throwing these people down. These tractors are maybe eight feet off the ground, and they start throwing and kicking people off—these people are tied hand and foot. They couldn’t break their fall. I heard bones snapping or dislocating. People were screaming. I’m looking at this corporal and going, Jimmy, what are these guys doing? These are detainees. And he looks up at my face and says to me with the coldest, flattest voice I’ve ever heard in my life, “Ehrhart, better keep your mouth shut until you understand what’s going on around here.” That was the point at which I first started thinking, What the hell is going on here? This isn’t what I signed up for.

Well, within four months, I was one of the Marines up on top of those tractors throwing people off. Within four months, I could not think of a single reason why I was in Vietnam, except to stay alive until March 1968, at which point I could go home. Every possible explanation I could come up with for what I was doing there had come up empty. There was just no way to make any sense of it. It was all nuts. I didn’t want to be there. And I didn’t want to die there. Early on I had been going to the chapel. The battalion chaplain came by and said, You know, I haven’t seen you lately. What’s going on?

Ultimately, I told them that I had all sorts of reservations about what I was doing, and what the hell is he [the chaplain] doing here, anyway? He’s supposed to represent the prince of peace! It was a hell of a conversation. Finally, he said, You know, there’s such a thing as a conscientious objector’s discharge. And I will help you with that if you want.

Well, my reaction was, Oh, no, you ain’t hanging that albatross around my neck. CO was the first two letters of coward as far as I was concerned. I told them, I’ve got four months left, I’ll take my chances. That’s what I did. I have spent a good deal of my adult life wishing I had had the courage to take him up on it. By then, even though I couldn’t articulate it clearly, I knew what I was doing was wrong. We were not helping the Vietnamese. We were not winning anything. It was crazy. But, basically, I just wanted to get the hell out of there in one piece.

And then I started college in September of ‘69. I went all the way through the first year of college, all while I’m telling myself, I don’t know what the hell’s going on over there. But if I’m out of it, and I got all 10 fingers and 10 toes, it ain’t my problem anymore. Meanwhile, I’m engaged in drinking and drinking while driving—incredibly self-destructive behavior. When I got to college, I added drugs to the mix. And then the Ohio National Guard murdered four kids at Kent State University. That hit me like a ton of bricks. I don’t know when I finally decided this war was wrong. But I know when I decided to join the anti-war movement, and that was May 3, 1970 [the killings happened on May 4, 1970].

At that point, I thought we really meant well, that we were trying to help the Vietnamese and that something had gone terribly wrong. But we were really good people. I spent the next year speaking out against the war, but not speaking out against the people that sent me there. And then the Pentagon Papers hit the streets in June of ‘71. And I read every piece I could get my hands on. And then I realized that the war was no mistake. It was 25 years of deliberate lies and half-truths and deception. And I’ve been angry ever since.

PRAYING AT THE ALTAR

by W.D. Ehrhart

I like pagodas.

There’s something—I don’t know—

secretive about them,

soul-soothing, mind-easing.

Inside, if only for a moment,

life’s clutter disappears.

Once, long ago, we destroyed one:

collapsed the walls

‘til the roof caved in.

Just a small one, all by itself

in the middle of nowhere,

and we were young. And bored.

Armed to the teeth.

And too much time on our hands.

Now whenever I see a pagoda,

I always go in.

I’m not a religious man,

but I light three joss sticks,

bow three times to the Buddha,

pray for my wife and daughter.

I place the burning sticks

in the vase before the altar.

In Vung Tau, I was praying

at the Temple of the Sleeping Buddha

when an old monk appeared.

He struck a large bronze bell

with a wooden mallet.

He was waking up the spirits

to receive my prayers.

Robinson

Let’s go back to your early months in Vietnam and dwell just a little bit on what you’ve described, which is quite a rapid shift. You showed up with the John Wayne story expecting to be greeted with flowers as a liberator of the people of Vietnam. And then, quite quickly, you’re contemplating any way to get the hell out. You mentioned witnessing Vietnamese detainees being horribly abused.

Ehrhart

Four months in a war zone is not a short time. It’s forever. It’s a long time. Day in and day out, we would run from fire. At one point, we got sniped at from a village and we called in an airstrike. It was just stuff like that, day in and day out. The first eight months I was in Vietnam, our battalion, which was about 1,000 men, encountered, on average, 75 mining and sniping incidents a month. Most of them were mines and booby traps, over half of which resulted in marine casualties. We were operating in a heavily populated civilian area, rice farming and fishing. Our boys are stepping on these booby traps and mines all over the damn place. The Vietnamese civilians aren’t stepping on them. They’re not getting blown up. It’s just us. How come they’re not getting blown up? Well, they must know where these mines are. Why won’t they tell us? We’re supposed to be helping them. Well, they might be planting the goddamn things! So next time you’re out on patrol and somebody steps on a mine, the farmer nearby doesn’t even behave like he hears the explosion. So you just blow him away. Day in and day out.

You patrol the same villages every single day for eight months, and nothing changes. And you don’t see any armed soldiers. I saw like eight armed guerrillas the entire first eight months I was there. There’s no one to fight, just explosions and guys lying on the ground screaming for their mothers. It makes you crazy. I never saw anything on the scale of a My Lai massacre, but I understand why some of those men did that—it was an impossible situation. What were a bunch of scared kids with guns supposed to do? It’s not like these folks were inviting us to dinner. The pitch was that the Vietnamese civilians were forced to help the Viet Cong. But no, that’s not at all true. We forced them to choose between the Viet Cong and the Americans, and that was no choice at all. All you had to do is send a Marine patrol through a village and the Viet Cong had all the recruits they ever needed. It was that simple.

There was a guy that was assigned to our battalion as an interpreter, a very intelligent man. He was an enlisted guy who had been drafted into the Saigon army when he was 18 years old. By that point, he was 24. He spoke English, French, and Chinese. He was one of the bravest men I’ve ever encountered. And he was not fond of the communists.

But at one point in September of ‘67, he walked into our battalion command post and basically quit. He said, “I’m not doing this anymore. You Americans come here with your tanks and your guns and your helicopters and your arrogance. And everywhere you go, the Viet Cong grow like new rice in the fields.” And I remember that phrase: Everywhere you go, the Viet Cong grow like new rice in the fields. “You’re destroying my country, and I’m not going to help you anymore.” And he quit. They put him under house arrest, and the next day they took him away. And if they didn’t put him up against the wall and shoot him, they probably sent him to some suicide Battalion.

I went to Hong Kong on my time off. And that was hanging on my head because I knew that this man was not a coward.

Robinson

There’s an incredible scene with an argument where he has this outburst where he says, “You don’t know what you’re doing. You’re ruining everything. You’re hypocrites. You’re fools. You’re giving my country to the communists. You need to take your ignorance and go home.” What struck me was your reaction. You were kind of insulted. We’re here to help you. How dare you?

Ehrhart

I was 18 years old. I was facing the destruction of everything I’d ever believed about the world I lived in, the country I lived in, and the person I was. All of it was destroyed. It’s hard to let that go. I was struggling with all of it. Ultimately, within a few years I realized I’d made a terrible decision. And it would haunt me for the rest of my life. I have never felt comfortable in the country of my birth since 1968. I’m here. I’m an American. I can’t deny it. Where the hell would I go? But I’m very uncomfortable being an American. I am more often ashamed of myself in my country than I feel good.

All the stuff that we were told about our country was mythology. It had nothing to do with what this country really is. And it’s going on now, all this talk about critical race theory. It’s called history. And people still can’t come to terms with it. We’re not the most evil nation on earth, but we have “American exceptionalism,” just like the British thought they were exceptional and the French thought they were exceptional and the Chinese thought they were exceptional. It’s just what powerful nations do.

Robinson

I imagine you would agree that Americans really don’t understand how bad the war was. We don’t appreciate, for example, what an airstrike on a little hamlet does, or what using heavy artillery against the population of peasants involves. It’s a hideous kind of violence.

Ehrhart

Of course. How can people who have never experienced war have any idea what it’s like?

We can look at Afghanistan. We stayed for 20 years, and the same thing happened there. What most Americans don’t know is that one of the things that really impacted the decision to get ground troops out of Vietnam was the anti-war movement within the active duty military.

By 1970, the wheels had begun to come off the military. By ‘71, it was almost dysfunctional. There were massive rebellions, with entire rifle companies refusing to take the field and refusing to engage the enemy. There were acts of sabotage. At one point, I think the USS Constellation was sabotaged by some sailors, and it had to stay in port in San Diego for like three months while they repaired the damage before it could go off to Vietnam. The active duty military itself said, We aren’t doing this anymore.

And the other component of the powerful anti-war movement was the Vietnam Veterans Against the War. By 1971, the VVAW was the driving force of the anti-war movement, especially when they got rid of the deferment system for the draft and went to the lottery. It was the veterans themselves who scared the bejesus out of the government. We’re not a bunch of hippie college kids. We’re the real deal. We were there, and we’re telling American people, This is bullshit.

You now have this all-volunteer military. Their entire ethos is self-directed. They’re a hermetically sealed world unto themselves. Their loyalty is to each other. How in the hell do you have a war in Afghanistan for 20 years and there’s no anti-war movement? That’s why.

You know, I taught for 18 years at Haverford School, a private school for boys. Not a single one of my students in all those years did what I did, which was to finish high school and say, I’m not going to college, I’m going to enlist in the military. Not one. I’ve taught the children of members of congress. I had a vice president’s nephew. These are people who could have an impact on the course of events. But why should they care what the hell is going on in Afghanistan? It’s not their kids who are going to die. You know, the “all-volunteer” military is really an economic draft. My rich kids at the Haverford school who all go to college don’t go into the military. It’s kids from North Philly and kids from Appalachia who go into the military.

The consequences of American foreign policy have been completely and utterly divorced from domestic politics. Doesn’t matter what the government does out there with your tax dollars in your name. Nobody cares. Why should they? I mean, I know why they should. But in day-to-day terms, they’re gonna have no skin in the game. They’re not gonna object. That’s how you can stay in Afghanistan for 20 years. And there’s no anti-war movement.

Robinson

I just did research for an article I wrote about the war in Afghanistan. There’s so much I didn’t know. Many of the horrific atrocities against civilians were never discussed. There were never any discussions about whether it made sense for us to be there, whether the corrupt and unpopular government that we propped up was even worth supporting. We funneled money to warlords. It’s out of sight, out of mind. You’ve called the Vietnam War a racist war. I think racism has something to do with the ability to sustain these wars. These wars are fought against populations that we don’t consider fully human or don’t relate to or don’t understand.

Ehrhart

Well, certainly there is a major element of racism involved in it. The only thing that I would qualify that with is that there were atrocities committed by American soldiers against German soldiers. I don’t think that the fighting got as vicious as it did in the Pacific War. But I just keep coming back to the reality that war itself is the crime. There was racism involved in Vietnam. But I think it has a whole lot more to do with trying to prevent the loss of Western control over the world’s economies.

At the end of the Second World War, the Western world was trying to restore the colonial subordination of the Third World. That’s what was going on. It was the attempted reinstallation of the world order that existed prior to 1939. And we were part of that. And the people who tried to tell the government what was actually happening in Vietnam were dismissed or exiled or fired. That’s American arrogance. That’s understanding the world in a certain way that is divorced from the facts.

Did you know Ho Chi Minh was our ally in the Second World War? We sent American soldiers to work with him and train him and give them equipment. The guys who were in charge of that group that worked with Ho in 1945 kept saying, This guy’s a good guy. He’s a communist, but that has nothing to do with what he’s up to. He wants to get rid of the French; he’d like to have his country back. And the State Department sent someone over to get the goods on Ho, and their guy comes back and says, No, this guy is a communist, but that’s not really relevant. He’s a nationalist, and you should really support him.

There was one choice the Americans had to make. And that was on September 2, 1945, when Ho Chi Minh stood in the square in Hanoi and declared the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh was a great admirer of American history and of Thomas Jefferson. And the U.S. government made the wrong choice. In fact, the conclusion that the State Department came to was that Chi Minh was such a good communist, he knew what Stalin wanted him to do without getting any orders to do it. That’s the conclusion they came to. You can’t make this stuff up. It’s arrogance on a cosmic scale. The idea that Russia was giving Ho Chi Minh orders and the Chinese were supporting … the Chinese and the Vietnamese hate each other!

The idea that the U.S. could have won the war in Vietnam is an absolute fantasy. The American people got tired of the Vietnam War within five years of ground troops being sent there. And within seven years, they were screaming bloody murder to get the hell out of there. The Chinese occupied part of Vietnam for 1,000 years. And there was rebellion after rebellion. Finally, in 930 A.D., it worked, and the Chinese were expelled from Vietnam. A thousand years—think about that. We got tired of it after five years. And we couldn’t beat them with 500,000 troops. The Vietnamese were going to fight to their last living soul because that was their history. They’ve been doing it for over 2,000 years. It didn’t matter what we did. We weren’t going to win. I went back to Vietnam after the war and in 1985 had dinner with two former Vietnamese generals. I asked one of them his opinion. He said different tactics wouldn’t have mattered. He said, “We were fighting for our country. What were you fighting for?”

Robinson

There’s a quote from you about how the Vietnam War is treated as a well-intentioned error. The beginning of the Ken Burns documentary says that it was a terrible tragedy begun by good men with good motives. You said that Vietnam was a “calculated deliberate attempt to hammer the world by brute force into the shape perceived by vain duplicitous powerbrokers and the depths to which they had sunk dragging us all down with them were almost unfathomable.” Perhaps you could comment on that.

Ehrhart

I don’t know if you saw the Burns and Novick film [The Vietnam War]. I was interviewed in it fairly extensively. And I was worried. My big concern was that it would be total whitewashed bullshit. It was pretty bad, but it wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be. I do think that the American people got a look at both the Johnson administration and the Nixon administration in ways that they had not fully understood. They’ve got that quote from Johnson in the summer of 1964 when he says, We can’t win this thing. It’s gonna be just like Korea.

He knew this six months before he sent the first combat troops to Vietnam. I think this is an eye opener for many Americans. But there’s so much that’s wrong with that documentary. The thing that you have to understand is that David Koch and Bank of America are not going to underwrite a scathing exposé of American imperialism. So they start off with that total bullshit business of, “Oh, they were well meaning, they knew exactly what they were doing. It’s all in the Pentagon Papers.” But they had to do that.

I can also tell you that they left the best material I gave them on the cutting room floor. They didn’t use any of the good stuff I gave them. The greatest flaw in that documentary is that they cover the entire 2,000-year history of China and Vietnam in literally one sentence. Now, if you don’t understand that relationship, you will never understand why we never could have won the war. It’s not an accurate history. But, you know, if somebody made an accurate documentary about the war in Vietnam, I’d be showing it to you and a couple of my pals in my basement. It would never see the light of day here. There actually are some very good documentaries out there. But they don’t get on PBS. You’ve never heard of them. Maybe you have because you spend some time with this stuff. But accurate information about the war doesn’t make it into the mainstream.

Robinson

What material of yours do you wish they had used?

Ehrhart

There was a scene that was cut where I described some of us guys out in the sand dunes doing nothing. We found this old Buddhist temple and we destroyed it. We knocked the walls in and collapsed the roof of this temple. I have photographs of us bashing this heavy wooden thing into the temple wall. And there’s a poem to go with it. And none of that made it into the film. The basic premise of their documentary was, “These poor American boys. These poor innocents were sent off to fight this terrible war. Wasn’t it sad?”

But we were a bunch of fucking armed juvenile delinquents, and that image showing destruction of the temple does not fit the image of American soldiers that they wanted to portray. The way they told it, we were innocent victims, and we were victims as much as the Vietnamese were. So that’s one thing that really irritated me. And there’s another thing. At one point this guy talks about how the anti-war movement abused him and called him a baby killer. Meanwhile, the visual image they show with that description is of a bunch of people basically dressed in coats and ties—middle-class clothing—holding signs at the gateway to a military base. They’re obviously not screaming anything, let alone doing anything abusive. They’re just kind of standing there, silently. And that’s the only illustration that Burns and Novick used to demonstrate these hostile anti-war people who were so unkind to the veterans when they came back.

And I told them the story about when I came back. I got home, and the very next day, I went off to a car dealer. And I took all the money I’d saved and bought a brand new 1968 Volkswagen Beetle. Only I didn’t buy that car. I was 19 years old. I had to give the money to my father. He bought it and was the owner until I turned 21. I also had to be on the car insurance policy of my parents as a dependent child. You understand what I’m saying? I’m a combat wounded Marine Corps Sgt. But as far as the state of Pennsylvania is concerned, I’m just a child dependent on my parents. You want to talk about being spit on? It wasn’t the anti-war movement that was doing the spitting.

Robinson

This makes me think about the POW movement and the ways in which stories are, after the fact, constructed as a way to help America preserve the idea that we were the victims of the Vietnam War, or to feel sorry for ourselves. Google says that 50,000 American soldiers died in Vietnam. I actually wanted to know how many Vietnamese, but that wasn’t what came up. There are also ways in which Vietnam is seen as an American tragedy that affected Americans, something that we should weep over.

Ehrhart

We imagine that the Vietnam War is this thing that happened to a bunch of American teenage boys. In reality, the Vietnam War is what this country did to the Vietnamese. That’s what the Vietnam War was.

What Reagan did was transform the Vietnam War by putting it into the mold of World Wars One and Two, defining it in traditional terms where we were the good guys. As for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, if you built a memorial to the dead of Vietnam, it would be as tall as the deepest part of the monument today. And it would run from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial up to the Washington Monument. That’s what 3 million dead looks like. But that memorial is all about us. It’s all about the Americans. And guess who paid for it? The veterans themselves. The whole initiative came from Vietnam War Veterans. We built a monument to ourselves. It’s embarrassing.

Robinson

There’s a poem where you say that you wanted an end to monuments. What you wanted was “a simple recognition of the limits of our power as a nation to inflict our will on others, understanding that the world is neither black and white nor ours.” The way that America remembers Vietnam could be the way we talk about the war in Ukraine. In 10 years it’ll be about how sad it was for the Russian soldiers.

Even the soldiers on the wrong side of a war do come home fucked up. They have to live their lives with horrible nightmares, they have to deal with pangs of conscience, and they die in huge numbers. Even the soldiers on the wrong side are in fact victims of war. But there are still ways that we can tell ourselves a wrongly self-pitying story about that war.

Ehrhart

We seem to be stuck with killing each other as a species for political reasons, which almost always comes down to money. And it’s never the people with money who end up getting killed.