What We Learned at Zohran Mamdani’s Inauguration

Mamdani’s mayorship is an unprecedented opportunity for the left. But ultimately, he's only as strong as the movement behind him.

It’s December 31, 2025, the day before Zohran Mamdani would be inaugurated mayor of New York City. Outside a small hotel front in the Garment District, hospitality workers from the Laborers’ International Union of North America (LIUNA) are on strike. They’re a small, huddled group in thick coats and beanies, standing around the building’s entrance and asking would-be customers not to cross the picket line as they approach. Their demands are familiar, and could have been made at any point in the last century. They want better wages, safety protections, and a fair contract. Backing them up is one of the city’s favorite sons: Scabby the Rat, the iconic protest balloon of the New York labor movement. He’s larger in person than he seems in photos, a little scruffy and battered around the edges—clearly a veteran of many such campaigns. His red eyes shine in the morning light.

A short distance away, a driverless Waymo taxicab advances down a different street. It’s slick, cold, spotless white. An invader from Silicon Valley, and the enemy of cab drivers everywhere, whose jobs, already pummeled by Uber, it threatens to further displace. On its roof and fenders, an array of surveillance cameras scans the streets, like the eyes of some malevolent cyborg god. Like many of the worst things in life, it’s “AI-powered.”

It’s eerie to encounter these two scenes in quick succession, on a historic day like this. They seem like omens, or avatars of the political forces that are currently fighting for control of New York City. On the one hand, normal working people, getting together in the streets and pushing for a better future—the exact kind of movement that has swept Zohran Mamdani to power. On the other, the inhumanity of Wall Street and Big Tech, trying to destroy people’s livelihoods and replace them with machines. Like Captain Ahab and the whale, Scabby and the Waymo—labor and capital—are locked in an existential battle, with the future of New York City and the world as the stakes.

photos: alex skopic

This is the conflict that will define Mamdani’s time in office, and the new mayor’s administration is one of the key battlegrounds. We don’t yet know which side will come out victorious. Mamdani’s voters may have won the race, but the billionaires who put Waymos in the streets, dinners on the backs of e-bikes, and young people in their bedrooms, alone, scrolling and talking to chatbots, are well-organized and rich beyond imagining. Talented and charismatic though he is, Mamdani is facing an uphill fight.

On the Threshold of Power

For the political left, Mamdani’s inauguration is an unprecedented moment of hope. It’s arguably the biggest victory the American socialist movement has ever had. Before, members of the Democratic Socialists of America have taken legislative seats, as with Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s shocking win in 2018, but they’ve only been a small minority in Congress, and never held executive power on this level. Suddenly, one of the DSA’s own will be running the biggest city in the United States, and one of the world’s most important financial hubs. In New York, everyone is talking about the incoming mayor, from local journalists to people in bars, bagel shops, and doctor’s offices. The energy in the city feels comparable to when Barack Obama took office in 2008—or, perhaps, when Bernie Sanders won the Nevada caucuses in 2020, creating a brief sense that the United States was about to have a socialist president. For people on the left, there’s a palpable sense of standing at a hinge point in history.

But with that hope comes an equal amount of uncertainty and doubt. Mamdani’s administration is a high-stakes gamble. If he succeeds in carrying out his ambitious agenda—free buses and childcare, higher wages, a rent freeze—it will serve as evidence that socialists can govern effectively, and would go a long way toward dismantling decades of propaganda that associates the word “socialism” only with 20th-century dictatorships. Mamdani could become the blueprint for a wave of future left-wing leaders like him across the country. On the other hand, failure would be catastrophic, and the left has been let down before. The surge of hope people felt when Obama took office was quickly dampened by the way he actually governed, abandoning progressive campaign promises and compromising with the right. The people who put their hopes in Bernie Sanders’ last campaign, too, ended up suffering a painful defeat. And it doesn’t help that we’ve only known Zohran Mamdani as a national figure for about a year—not long enough, necessarily, to fully trust him.

A few of Mamdani’s pre-inauguration decisions have raised alarm bells. Foremost among them is the decision to retain Jessica Tisch, who served under the Eric Adams administration, as commissioner of the New York Police Department. Tisch comes from a cartoonishly wealthy family of hotel-owning billionaires, to the extent that her father Jim was once sued for wage theft by his butler (yes, really); Jonathan Tisch reportedly donated $1.3 million to an anti-Mamdani Super PAC. Tisch also has a disturbing track record of going light on killer cops, including a case this past August where she defied the recommendation of a civilian review board and declined to punish an officer who killed an unarmed Black man, Allan Feliz, at a traffic stop. To say the least, the thought of someone like her being in charge of New Yorkers’ safety is concerning.

Then there was the controversial DSA endorsement process where Mamdani weighed in against city council member Chi Ossé’s bid to challenge Hakeem Jeffries for his seat in Congress, angering parts of the left. Mamdani then offered about as forceful an endorsement of Jeffries as Kamala Harris offered of Mamdani: a one word confirmation (“Yes”) that he wanted Jeffries to be the next speaker of the house, declared on “Meet the Press.” It was tepid, but there. Likewise, Mamdani’s July announcement that he would “discourage” the use of the word “intifada” at Palestine protests has alarmed some activists, and there are lingering questions about how well he’ll be able to defend immigrant communities in the face of President Trump’s ongoing ICE raids.

“I’m excited about the possibilities, but, you know, also cognizant of the challenges that lie ahead,” Alex S. Vitale tells us. He’s an expert on criminal punishment and police reform whose 2017 book The End of Policing became a national bestseller. Mamdani tapped Vitale to join his mayoral transition team, which included over 400 community activists and advisors on a wide range of subjects. (Though, as some have anonymously leaked to City and State NY, sidestepping an NDA, the transition teams’ input has largely been limited to a few meetings and feedback submission forms.) The New York Post wasn’t very happy about Vitale’s appointment, warning that it was a sign Mamdani “will push cop-hating policies as mayor.” In person, though, Vitale is a much more careful, measured thinker than the caricature the tabloids create of him. We met in a quiet reading room at the Brooklyn Public Library, where outgoing mayor Eric Adams once slashed budgets for weekend services in order to hand more cash to the NYPD.

“We're up against a very powerful, entrenched institution,” he says. “And even when we've seen mayors make demands on their police forces, the police sometimes just don't follow those demands. So I don't think we should be assuming that we're going to immediately see a radical transformation in policing.”

For Vitale, one major test of Mamdani’s administration will be the fate of the NYPD’s infamous “gang database.” Created in 2005, the database has been widely criticized by civil rights groups for the way it profiles racial minorities—a striking 99 percent of the people listed are either Black or Hispanic—on extremely thin grounds, often labeling people as “gang-affiliated” based on nothing more than the neighborhood they live in, the way they dress, or a “social media analysis conducted by the NYPD.” There are over 13,200 names on the list, some belonging to children as young as 11 years old. Together with organizations like the GANGS Coalition, Vitale has been working to abolish the database for years, and with Mamdani in power, he might have an opening to finally get it done.

“We have both litigation against the city that points out the ways in which this database is unconstitutional, and we have a bill before the city council that would eliminate the database and any similar kinds of databases. And of course, it's the hope of this movement that the Mamdani administration will take steps to move the city away from that gang suppression style of policing,” he says. Yet there’s a big roadblock in the form of Commissioner Tisch, who has defended the database as recently as August, saying that “calls to get rid of this tool are dangerous.” In that way, whether the gang list stays or goes could be an important indicator for how Mamdani plans to handle the NYPD more broadly.

“I think that the emphasis should be on building facts on the ground in the neighborhoods, around how we really create public safety, and that's going to create the political space that's going to allow us to then revisit what is the appropriate role of police,” Vitale says. In other words, from what we have seen so far, simply having Mamdani in a position of power is not a guarantee of reform, police or otherwise.

Celina Su, another member of Mamdani’s transition team and an expert on city budgets, expressed a similar mixture of hope and concern for what lies ahead. She’s the author of Budget Justice: On Building Grassroots Politics and Solidarities, a department chair in Urban Studies at CUNY, and a regular contributor of poetry to Current Affairs. We met in person for the first time at a Yemeni coffee shop, where she underlined the potential of the Mamdani administration, and by the same token, what is at stake: “We need to go beyond just getting rid of corruption and graft, which of course is necessary, to really try to set new precedents for new ways of governing.”

The core of Su’s political project is participatory budgeting: the idea that cities shouldn’t decide where to allocate taxpayer money based on opaque internal processes, which are vulnerable to lobbying by corporate interests, but instead welcome the input of the entire public. So far, this has only been tried on a limited scale in New York, but Su hopes to see the Mamdani administration carry the idea further.

Here, too, there have been some initial question marks. Mamdani originally seemed to be fully onboard with the idea of making public decision-making more democratic, promising to end the system of “mayoral control” that concentrates decisions about New York City’s schools almost entirely at City Hall. It’s a vestige of the reign of Michael Bloomberg, who dissolved the city’s elected school boards in 2002. In the week of his inauguration, though, Mamdani abruptly reversed course and said he’d keep mayoral control after all.

“I don't know exactly what it indicates, because I'd have to admit that I was a little bit surprised as well,” Su says. “Hopefully the Mamdani administration will be able to allow for more substantive public engagement even within the mayoral control system, and we'll see what comes next.” For her, the first actual budget proposal under the new administration will reveal much more. “I would say a red flag would be if there were no changes to big budget numbers such as police over time—we need more realistic ones.” Ultimately, she says, “the public is going to have to put pressure on Mamdani in order to get things done.”

When it comes to divining the motives behind Mamdani’s actions, perhaps no one outside his administration is better equipped than Ross Barkan. A political columnist for New York magazine and the author of a forthcoming book on the mayor, Barkan has known Mamdani for almost a decade; when he ran for the New York state legislature in 2017, Mamdani served as his campaign manager. We caught Barkan at a bar near City Hall in Manhattan. It was a frigid afternoon, and he was huddled in a booth against the wall, still clad in a thick coat and hat, clasping a mug of hot black tea. “I think he’s earnest about delivering on his policy, I do,” he said. “I think if he has to pivot and compromise to a degree, for the purposes of politics and the electorate, he’s going to. But I don’t expect him to abandon the core planks of his campaign. That would surprise me.”

Still, like a lot of people, Barkan foresees trouble brewing with Jessica Tisch and the NYPD. “He is going to have to reckon with their deep ideological disagreements, and also reckon with the fact that because she's so wealthy, she does have a certain invincibility. She's not invincible, but having that degree of wealth in the political arena can insulate you from a lot,” he tells us. And if there’s a crisis involving police violence, he adds, that underlying conflict could flare up in some highly damaging ways. “If Jessica Tisch is saying one thing about this police involved killing, or one thing about this cop who was killed, and then Zohran is just saying something entirely different, it's going to be hard to square all that, and I don't think he has an answer. I think he's hoping that she will defer to him as mayor, which is true, but easier said than done.”

For Barkan, it’s all about delivering those “core planks,” and Bernie Sanders’ time as mayor of Burlington, Vermont is the blueprint. “Bernie is one of the rare left-wing politicians in America who had to oversee a city. It was a small city, but he had to make decisions around budgets and policing and who works for the administration. And it's not glamorous, it's not fun, it's not overly interesting to people, but it matters to the working class like you need,” he says.

That’s why Mamdani’s decision to avoid backing Chi Ossé in a high-profile race against Hakeem Jeffries doesn’t bother him. “He must do a great job in New York City. That's why he's so focused, because you can't just say, ‘I'm going to be a national leader now’ and go float around. Because if he's perceived as being inattentive to the city, if he's perceived as not achieving his promised policy outcomes, there is no left future for him.” On the other hand, if Mamdani does deliver on his core agenda, the downstream effects could be enormous. “He's so young, and he's going to have a long political afterlife. And so is there a universe where, after eight successful years, Zohran Mamdani is the celebrated former mayor of New York City who can go around the country and campaign for candidates and build up DSA and build up the left. Yes. I mean, I think success, you know, national leadership and success in that realm will come through New York City.”

Mamdani is walking into a pit of vipers, everyone knows that. In City Hall, he will be surrounded on all sides by powerful representatives of the real estate industry, the police, the pro-Israel foreign policy establishment, and a dozen other forces that badly want him to fail. Just as many will be trying to co-opt him, replacing his current ideas and principles with their own. Nobody, not even the most talented politician alive—and Mamdani is clearly one of those—can overcome those forces alone.

“What makes him unique, really, genuinely unique, is he is the only New York City politician I’ve seen with a mass following,” Barkan tells us. “There’s never been anyone like him—Giuliani, Bloomberg, Eric Adams, De Blasio, Dinkins, you can go back to Koch. No one. Nothing like this. He could fill Madison Square Garden tomorrow, if he wanted. It’s a weapon.”

Going forward, everything will depend on how well Mamdani utilizes that weapon. Obama discarded his own, quietly disbanding his volunteer force once he was in office. Mamdani can’t afford to make the same mistake.

“I think if he's smart, he's going to learn from another guy who he's not going to invoke in this way, but I will, because I'm not a politician: Donald Trump,” Barkan says. “Why did Donald Trump keep having rallies? Well, how is Donald Trump able to, through losing a presidential campaign, continue to be so relevant out of office? I think there's a lesson for the left there. I mean Trump’s the dark version of this, but there's a light version of Trump. There's a positive version of Trump, where you can have political rallies, you can bring people into the mix.”

The night before his inauguration, the mix that elected Mamdani is watching him closely. By one estimate, 90,000 people volunteered for his campaign. Throughout the electoral process, and with a singular elegance, Mamdani traded on their energy and groundswell of grassroots support, generated by years of their own organizing, years of their own relationship building, years of living in and learning from the unglamorous, increasingly dysfunctional realities of New York City. He won by uniting so many disparate groups and movements—like Vitale’s, like Su’s, like the Democratic Socialists with whom Mamdani has organized for a decade—and channeling them, focusing them together with laser-like intensity. The question now is one of follow-through. The people who elected Mamdani are no fools. They’re tired of politicians who fail to deliver, and if Mamdani allows his momentum to be diverted and weakened, his base will tire of him, too. More so than they need him—there’s always another politician to be found—Mamdani needs his electorate if he wants to have success in office.

“We Da Mayor Now”

The sky on New Year's Day paints an almost uninterrupted blue over City Hall. The building itself is an old one, stone white, only interrupted by a banner stretching across its front reading "INAUGURATION" in block letters, written in a serifed font and a bright shade of navy now instantly recognizable in New York City as the mark of Zohran Mamdani.

Standing outside City Hall’s gates, it’s really, really cold. The temperature sinks into the 20s, and we fantasize about space heaters, or at least the body heat that might await us on the other side of City Hall’s head-high iron fence. Unfortunately for us, there’s a clear hierarchy to the media in attendance, and prestige is not its primary metric. Rather, each member of the press who files in is asked some version of the following: “New media, digital media, or print media?” New media—Instagram influencers, TikTokers, YouTubers and their ilk—are seated with regular attendees, on cushioned white folding chairs that wrap around the building’s front steps, where Mamdani will repeat the vows of inauguration he first took at midnight in the subway station under our feet. Digital media has a raised platform behind the chairs where cameras are set up in front of cable news anchors with long wool coats, bronzed makeup and clunky headsets. A Mamdani volunteer leads us, the print media, past the chairs, past the platform, to where us pencil-pushers are to be stationed: a few chairs and folding tables set behind the cameras, in the bushes. If we want to leave this area, we have to ask for an escort. Throughout the day, when nature calls, we are escorted to the porta-potties by Mamdani’s staff, where they wait for us to finish, then deposit us back in our designated area.

The print journalists cluster around the rope dividing us from the attendees and watch as the audience files in, a little envious of the new media people moving freely about. “It’s because they don’t ask any hard questions,” one reporter quips about the TikTokers' far better access. It may also be because print media has never been a core part of Mamdani’s communications strategy. Vertical videos, on the other hand, helped propel him to stardom.

From what we can see, those in attendance are young and chic. Sunglasses are huge, outfits are well-tailored, and red Democratic Socialists of America hats dot the crowd. A DJ table is set up on the stairs of city hall, and DJ mOma is playing music every millennial has danced to at some point: Mariah Carey’s “Fantasy,” Queen Pen’s “Party Ain’t a Party,” DMX’s “Ruff Ryder’s Anthem.” Plus, inevitably, Frank Sinatra singing “New York, New York.” At the booth, three women dance and rock back and forth with the music. The energy is high. Today, Brooklyn is in Manhattan.

“It felt like a club,” DSA member Alex Pellitteri said. “We were dancing. It felt very joyful.” Pellitteri is a friend of Mamdani. They met when Pellitteri was just 17, working together on the campaign of Palestinian Lutheran Minister Khader El-Yateem, who was running for City Council. Mamdani then hired Pellitteri as a staffer on Ross Barkan’s state assembly run. “On New Year's Eve, when everyone was partying and drinking, I was thinking about how this guy who I kind of goofed off with is now going to be the next mayor,” Pellitteri said in an interview after the event. “And how just a few years ago, no one knew who he was. But I think that's just a testament to DSA, the ideas that he ran on, and I think that people did not want more of the same.”

Much of the crowd acts like they know each other, because they do. There are plenty of DSA members, to be sure, but also the broad coalition who worked for Mamdani’s election. “We sat down next to somebody who works for New York Immigration Council, or somebody who’s a union organizer. We’re talking about our experiences on his own campaign,” DSA member Lawrence Wang said, also interviewed after the event. Wang ran the DREAM, the anti-Cuomo and anti-Adams Super PAC. New Yorkers may remember their hats, embroidered with their breakthrough messaging, “Don’t Rank Eric or Andrew for Mayor.” “I was right next to the entrance. So every person came in[...] it's like, face after face of people I knew. And we're like, ‘Can you believe it? We’re here. Started at the bottom, now we’re here.’”

The guests of distinction begin to file in on stage. Senator Bernie Sanders, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and New York Attorney General Letitia James emerge to cheers. Lina Khan, the anti-monopoly shark of the Biden administration who Mamdani has recruited to NYC, sits down with the Mayor’s transition team. Bill de Blasio takes a phone call from the stage before the ceremony begins.

Joining them are establishment political figures, many of whom have made known their wariness of Mamdani and their opposition to genuinely left-wing politics. There’s New York Governor Kathy Hochul, who will have to approve the tax increases Mamdani campaigned on, namely a two percent increase on households making over one million dollars. Hochul has publicly said she has no plans to raise taxes. Behind her sits New York Senator and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, who did not endorse Mamdani and has spent the past year rolling over like a dog for Trump, drooling from the mouth. The infamous, corrupt outgoing Mayor Eric Adams has decided to make an appearance after weeks of public waffling.

As the day’s speeches begin, it becomes clear that the politicians making them have absorbed the left’s anxieties of the past few weeks—their questioning of Mamdani’s intent, his loyalty to his voters. Representative Ocasio-Cortez declares the day “a historic new era for New York City,” but continues with a call to action, a plea. “New York City, this is an inauguration for all of us,” she continues. “Because choosing this mayor and this vision is an ambitious pursuit. It calls on all of us to return to public life en masse. Now is the time to turn toward our neighbors, stand with them, and return to community life. A city for all will require all of us to fill our streets, our schools, our houses of faith, our PTAs, our block associations as we support this mayor in making an affordable city a reality for all of us.”

Mamdani’s hero, Senator Sanders, puts a finer point on this. “Running a great and winning campaign was extremely difficult, but governing a city of eight million with all of its complexities and all of the problems that Zohran is inheriting will be even harder. Zohran needed your help to win this election. Now he will need your help to govern. Grassroots democracy and people participating in the day to day struggle of this city will lead to good governance. Please, remain involved.” The crowd cheers.

It’s an acknowledgement that Mamdani’s policies are far from settled fact. Mamdani cuts a remarkable figure, but never mistake the persuasiveness of a politician for the intelligence and power of their base, whom they channel and reflect, but do not invent. Changing the way a city like New York runs requires more than political acumen. It needs public pressure. As the nation’s preeminent socialists speak, they are locking eyes not with Mamdani, but his movement, and saying we still need you.

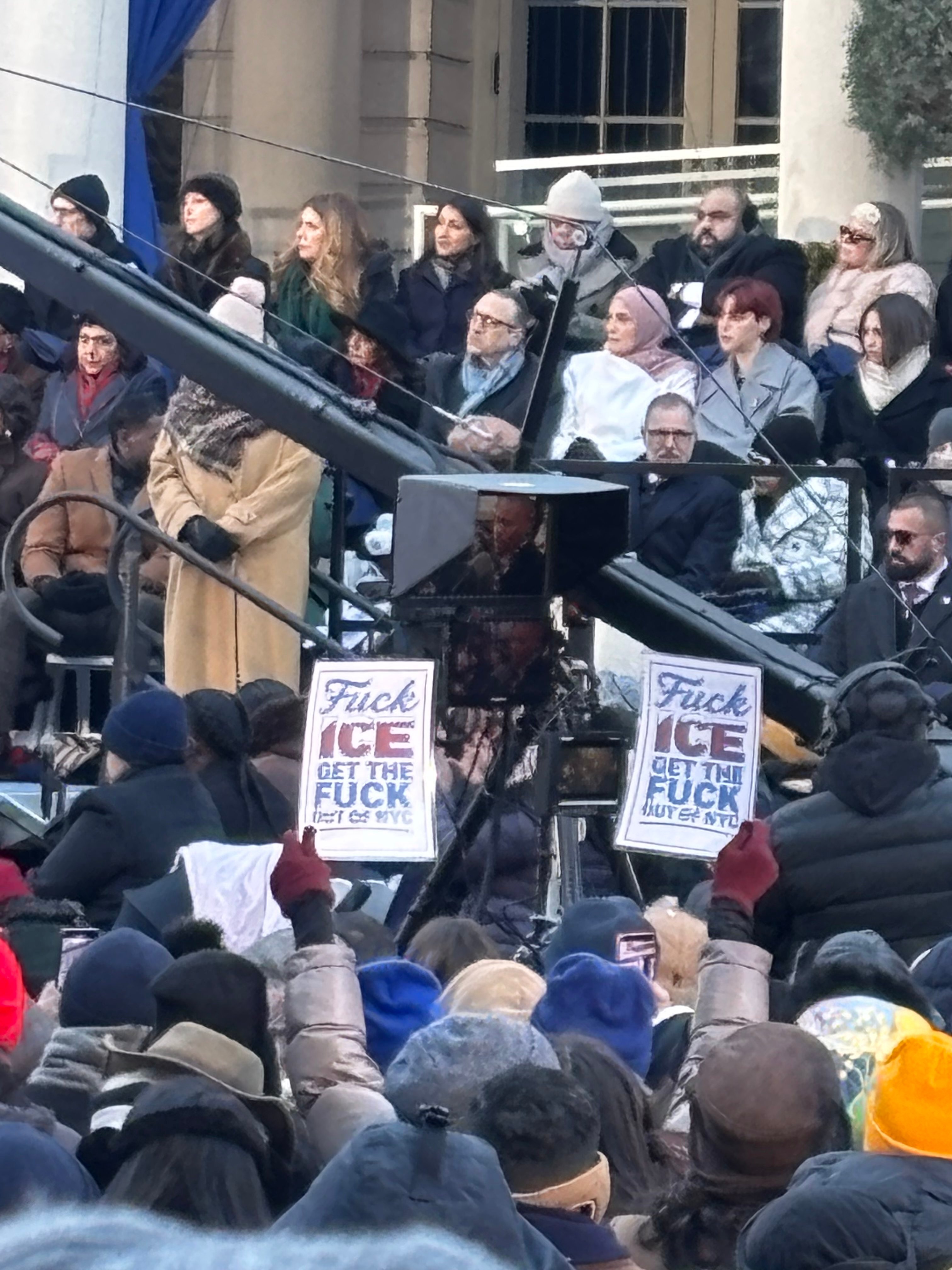

Before Mamdani could even reach the podium, those who elected him make clear their positions. Someone in the crowd holds up a large “Fuck ICE” sign, and for almost the entirety of the inauguration, another attendee holds an image of Hind Rajab—the five-year-old girl who was murdered by Israeli forces in Gaza in 2024—high in the air, where the cameras could see it. It’s a potent reminder of the literal life-and-death stakes of the Palestine issue. Mahmoud Khalil, the Columbia graduate student who was abducted by ICE for his activism, is also in attendance, along with numerous other young activists in keffiyehs and clothing bearing the Palestinian flag. None of them will allow Mamdani to forget the commitments he’s made.

photo: emily carmichael

Even within the crowd, the big political issues are being contested. In particular, Hochul’s presence was not lost on Wang. When he saw her walk on stage, Wang and his friends decided they had to start a “Tax the rich!” chant at some point during the ceremony. “We need to find the right moment,” Wang says after the fact. “And then Bernie Sanders set it up for us on a fucking tee.” Sanders, as he is wont to do, said, “Lastly, and maybe most importantly, demanding that the wealthy and large corporations start paying their fair share of taxes.”

It is one of the biggest applause lines of the whole event; the crowd stands up, exultant, whooping and clapping. “And on a shot,” Wang said “our group started immediately going ‘Tax the rich! Tax the rich!’” Many quickly join in. Mamdani laughs to himself, Sen. Sanders smiles, and the instance became one of the most viral of the inauguration.

“Even in a moment of our greatest triumph so far, we're not done,” Wang said. “We're still out here waiting for the moment where we can tell Kathy Hochul, if you don't tax the rich, there are gonna be consequences for this, and you won't like them[…] This is an expression of power[…] All these people standing up, chanting tax the rich, while Kathy Hochul, Chuck Schumer, the political elite, Democratic establishment, are watching and just going, ‘Oh, shit.’”

Mamdani would speak for nearly 25 minutes. His speech seems crafted to assuage the concerns of those who elected him, who smile and shiver as Mamdani declares we are “warmed by the January chill by the resurgent flame of hope,” and boo as he cheekily thanks Eric Adams, and just about everyone else he could think of. His mother tears up. Mamdani then re-committs to his campaign positions, including those that some had started to doubt. He will freeze the rent. He will make buses fast—“and free!,” the audience finishes his line, well rehearsed in the mayor’s promises. He will tax the rich. He declares that there will be a department of community safety “that will tackle the mental health crisis and let the police focus on the job they signed up to do.” He speaks directly to Palestinian New Yorkers in Bay Ridge “who,” he says, “will no longer have to contend with a politics that speaks of universalism and then makes them the expectation.”

His speech is actively against the idea of pivoting, becoming more moderate once in office. “In writing this address, I have been told that this is the occasion to reset expectations, that I should use this opportunity to encourage the people of New York to ask for little and expect even less,” Mamdani says. “I will do no such thing. The only expectations I seek to reset is that of small expectations.” He makes clear what that entails: “I was elected as a democratic socialist, and I will govern as a democratic socialist.”

“That’s probably the first time in history that a New York City mayor mentioned DSA twice in his inauguration speech,” Pellitteri said.

Throughout Mamdani’s speech are the same calls for public life, albeit more poetically articulated, that came from Representative Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Sanders. “I ask you to stand with us now and everyday that follows. City Hall will not be able to deliver on our own,” he says. “No longer will we treat victory as an invitation to turn off the news. From today onwards, we will understand victory very simply: something with the power to transform lives, and something that demands effort from each of us, every single day.”

Or, more colloquially: “In the words of Jason Terrance Phillips, better known as Jadakiss or J to the mwah, ‘Be outside.”

“At the end, it felt like, you know, a real moment of yes, after all these years of fighting to have real democracy and a voice, not only to have a real champion of it, but also to be a part of it, not just a single person, but all of us are a part of it,” Wang said. “To see that happen and then being there with all these other political elites, the cultural elites and the media … But have a sea of red and blue and purple and the orange hats showing the power left, and the fact that Zohran had invited us, because we're not going anywhere.”

Mamdani’s movement is here, and not to be unheeded. As Wang and his friends like to joke, “We da mayor now.”

Over a century ago, another charismatic American socialist brought the movement to the highest level of reach and influence it had seen thus far: Eugene V. Debs, who built the Socialist Party to a membership of 118,000 at its peak and won roughly a million votes for president in 1912. (Today, the DSA is still catching up to Debs, with 90,000 members announced this past November.) In a famous speech in Canton, Ohio, Debs rejected the politics of personal ambition and narcissism that has so often dominated American public life, casting scorn on the public officials who “say, in glowing terms, that they have risen from the ranks to places of eminence and distinction.” “I would be ashamed to admit that I had risen from the ranks,” he said. “When I rise it will be with the ranks, and not from the ranks.”

That’s the message Zohran Mamdani should remember today. He has a unique opportunity to advance the cause of the U.S. left, one he’s achieved by calling upon the broad ranks of New York City’s working class and beyond. He’s cultivated a sense of community that is all the more striking in contrast to the widespread crisis of alienation and loneliness that’s swept American society in the last few years. Plenty has been written about this, and a few different factors are usually blamed, from the lingering effects of the COVID pandemic and its lockdowns, to the way Big Tech and its algorithms encourage people to spend all their time staring at their smartphones behind closed doors. But the Mamdani campaign, and the broader social movement around it, have put a crack in all that, running everything from scavenger hunts and soccer tournaments to the huge block party that surrounds the inauguration. The notion of a shared public life has begun to creep back into the city, and at the inauguration, it was on full display.

However, it’ll all be for nothing if this broader movement goes back inside. That could happen for any number of reasons: if Mamdani demurs in his commitments, or if Big Tech succeeds in its business plan of making people sit by themselves and scroll through as many ads as possible. Then Mamdani would lose the backing of a powerful, broad-based movement, and he’d be easy pickings for his deep-pocketed enemies, who are already preparing to move against him. And this is something his supporters, for their part, should remember as well. It would be easy to slide into hero-worship and uncritical support for whatever Mamdani decides to do, but that too would be a fatal mistake. He needs a movement that will back him up, yes, but also one that will hold him to the mark. The only way to truly be sure he won’t backslide, compromise, and make friendly deals with the establishment, the way so many other politicians have before, is to make him more afraid of angering his base than he is of angering the opposition. Ultimately, Mamdani is only as good as the movement behind him. In the months ahead, everything will depend on what he does with that movement.

%20(1).png?width=352&name=obrien-trump%20(1)%20(1).png)