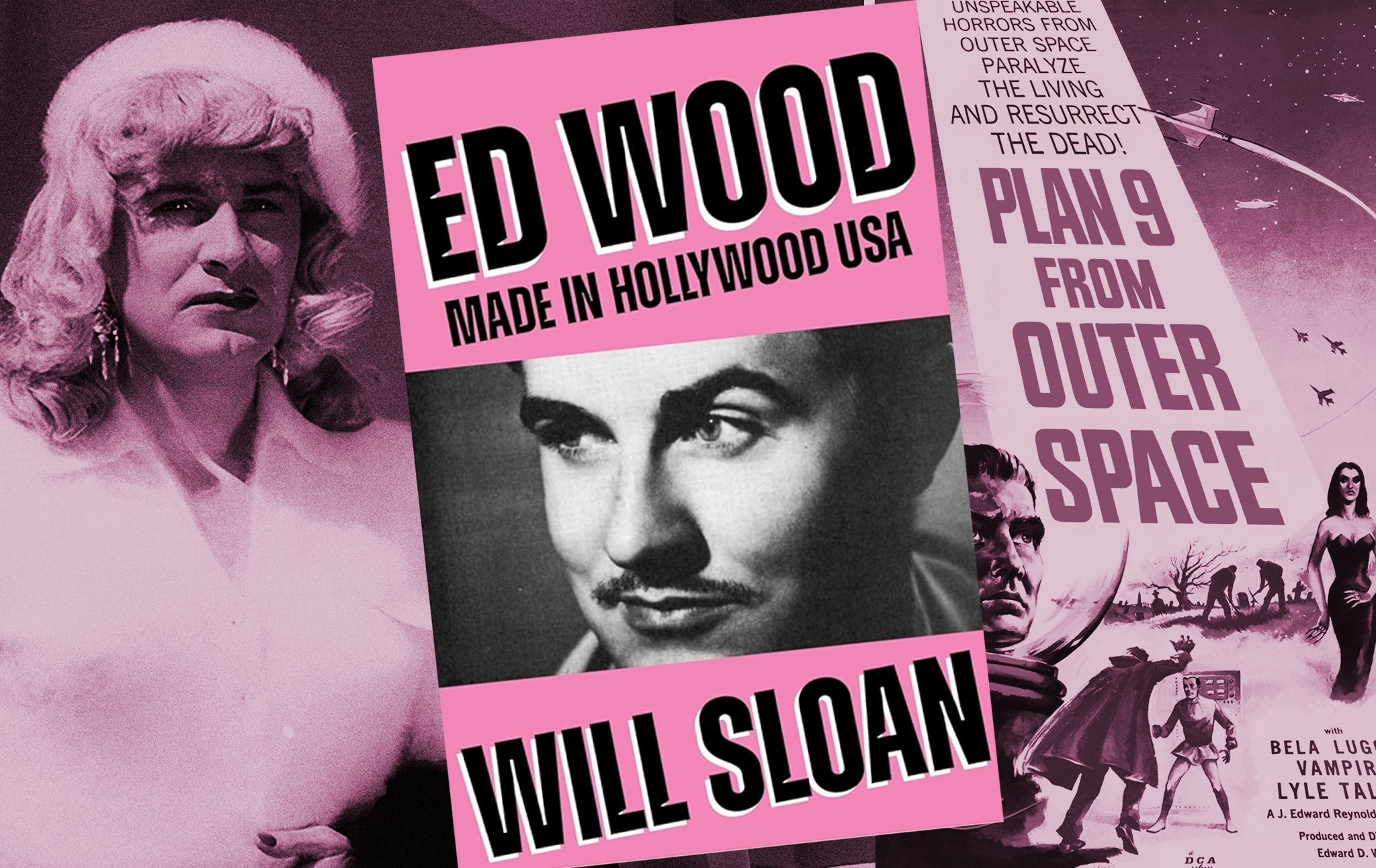

Film writer Will Sloan argues that he'd take "the worst film by Ed Wood over every film by Ron Howard." He makes the case for an infamously "bad" director.

Robinson

The way he does the nightmare sequence, portraying the agony of someone who is trans and has these desires in 1950s America, is wild. And also, you realize this guy did not have access to good actors because he didn't have any money. He had to use stock footage. He had to use bad actors. He had to improvise with the elements that he had. And someone in the book compares him to a junk collector who's going, Well, I can get Bela Lugosi. He's washed up, and he'll work for cheap. So can I have something with Bela Lugosi? The way this guy does this with nothing is pretty remarkable.

Sloan

No, absolutely. The imagination of it is extraordinary. The way that the film came about was Ed Wood had been kicking around Hollywood for about five or six years. He directed some commercials; he directed some community theater, but he wasn't really getting anywhere. And a producer named George Weiss, who made such films as Test Tube Babies, Olga's Dance Hall Girls, Racket Girls, and Dance Hall Racket—the classics—announced that he was going to make a film about Christine Jorgenson, who was the first publicly out transgender woman in America and the first highly publicized case of a sex reassignment surgery. He announced he was going to do this in the trades, and Ed Wood went to him and said, I have to make this movie; nobody in Hollywood is more qualified to make this movie, because I've lived it, which is very powerful.

George Weiss was not impressed by that, but he was impressed by the fact that Ed Wood knew Bela Lugosi, and it's like, okay, we got a star. We can put a star on the poster, and that's how he did it. But if you look at any of George Weiss's other movies, I think they have their moments, but you can imagine how another one of George Weiss's stable of directors would have made it. It would have been a pretty bog-standard, and probably pretty moralistic, film. A lot of the sort of roadshow exploitation movies were claiming to be against the thing, and Ed Wood fills it with so much ambiguity. He fills it with so much of himself. And also just because Ed Wood loves movies, indiscriminately and kind of without a lot of taste, he's just throwing a lot of movie stuff at you. So it's like, I love Bela Lugosi—I love Lugosi when he plays a mad scientist. Let's have a scene where Lugosi is pouring some beakers and crap like that. Because that's what he does in movies, right?

Robinson

Well, the war footage. The devil.

Are there any other sympathetic portrayals of trans people on screen in 1953? Maybe. But the end story about the guy who turns into Anne is not even just a case of transvestism. That is an actual transgender story where the man goes through surgery, and he shows once this person becomes Anne, she's living a happy life. And when you consider what American society was like in 1953, this is just so bold to do this.

Sloan

You would have to go decades into the future to maybe a movie like, I don't know, Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean to get a more sympathetic portrayal of a trans character, or even just a portrayal of a trans character, and a lot of that had to do with the fact that Glen or Glenda was an independent film. The studio system, the studio movies, which had a veritable monopoly on the major exhibitors at the time, were bound by the censorship rules. They were bound by the production code. So if you wanted a movie to pass censorship and to play in normal, above-ground theaters, not only could you not have a transgender character, you couldn't have a gay character—you couldn't have a man and a wife sleeping in the same bed in a movie back then.

So, George Weiss and Ed Wood were making these films that would play in kind of sleazy downtown theaters or drive-ins. They would basically be sold state by state because every state had its own censorship bureau, and from state to state, they would have to argue the merit of this film and the importance of this subject matter. Because you weren't allowed nudity in mainstream movies in the '40s and '50s, that was the domain of these independent producers. But because these independent producers also had to individually fight with local censorship boards, they had to claim that there was morally redeeming value to the nudity.

So you'd get all these movies about venereal disease, where you would have images of pox-ridden genitalia and the birth of a baby and stuff like that. People would go see these movies because it was such a repressed society, and they wanted to see a movie that was about sex and to be like, Well, okay, there's a vagina—there may be a baby coming out of it, but it's still a vagina. So yes, there are a lot of reasons why there weren't very many movies like Glen or Glenda. Some of them were ideological, and some of them were industrial.

Robinson

And when you think about just how common homophobic jokes have been in comedy, sitcoms, and comedy movies into the '90s and 2000s, American culture has been so aggressively transphobic and homophobic. This film is marketed as kind of lurid—the original poster has "I changed my sex!" on it. The marketing poster makes it look like a kind of freak show thing, and then you get to it, and it's this very earnest plea for tolerance.

Sloan

No, it is very powerful. And when this movie plays in theaters now, as it sometimes does—it will sometimes show in repertory theaters—in my lifetime, I have seen the general tenor of the audience go from "we're here to laugh at this" to "we're here to have sympathy with it." We all know this movie is flawed and that there are things in it that are funny, and I think denying that does the movie no favors. But, yes, you could just feel it in the air that people want to like this movie in a way that's different than they did 20 years ago.

Robinson

I want to get your position clear here on whether Ed Wood is, in fact, a bad director, because one of the things you're not saying is that these films are good according to certain standard criteria. You're not totally redeeming it; you're saying what you see as flaws in this film, like his dialogue. The acting often is terrible, and the dialogue is often things that people would never say. In a hilarious way, Plan 9 begins with that great monologue that goes like, Future events like this will happen to you in the future, and then it turns out to be about events that are happening in the past anyway. You think: Who wrote this?

Sloan

Yes, and I mean things like that—I'm not even sure I fully define to myself what a good and a bad movie is. I think it's more a spectrum than a binary. But I kind of had to confront that when writing this book, because essentially, my argument boils down to that he's not merely bad, that there's a lot in him that is of interest. There's a pretty obscure film that he directed, only half an hour long, called Final Curtain, and the story of that movie is—it's a mood piece. It's kind of like a Twilight Zone episode where there's an actor who's at an empty theater late at night. The audience, the cast, and the crew have gone home. It's just him in this theater, and he feels compelled by this force in the darkness, basically, and in practice, what this means is, for 30 minutes, you're watching a man stand on a stage while the narrator is going, "What is it in the dark? Was it a ghost? Or was it just the wind?"

And you're watching it, and what he's going for is to create atmosphere and tension through cinematography and editing. He fails. It didn't work. It's not at all convincing. But I kind of like the moxie of it. So when I boiled it down, certain things that I would define as being necessary to qualify as a good director, such as the ability to generate tension through editing and the ability to manufacture atmosphere through production design and cinematography, he was not gifted in that. But he was a unique guy. He did have a weird worldview that was consistent through these movies, and that's not nothing.

Robinson

The eccentricity here goes beyond merely being talentless. There's a way in which he absorbed all these movie clichés and then put them in a blender, and then what comes out is so clichéd that it's surrealist.

Sloan

Yes.

Robinson

And Lynchian and eerie.

Sloan

You're right.

Robinson

Tell me more about what this effect is that kind of happens, why it happens, and why it is interesting.

Sloan

I certainly agree that some of these movies are like putting a lot of clichés into a blender. One of the things I find endearing about Ed Wood is he clearly loves movies, and he wants to have all the movie stuff in his movies. So, for example, in Plan 9 from Outer Space, which is about a secret alien invasion of the United States, there's one scene where saucers are flying over Hollywood. You've got people on the highway who are pointing at the flying saucers in the air. Saucers are everywhere. Then in the next scene, the military has this mighty battle with the flying saucers. And when the saucers leave, two army guys are there, and they're saying, "Well, flying saucers are still a rumor officially; we've got to keep this under wraps." There's another scene where the hero of the film says, "I saw a flying saucer, but I've been muzzled by the army. But it's off the record. We can't say anything. They blew up a whole town, but it's been completely scrubbed."

And it's like, okay, the Martians, though, are on the front page of the newspaper. They're hovering at low height above Hollywood, and everyone is seeing them. It kind of comes down to Ed Wood wanting a scene where somebody in the army says, "This is top secret; this cannot get out" and he wants a scene where flying saucers are over Hollywood. Because both of those are scenes that are in movies like this.

Robinson

So why not just put both in then?

Sloan

Yes. And I love that. I think that's great.

Robinson

Don't think too hard about whether that's logically consistent.

Sloan

Anyway, as I'm saying that, though, it's not like the powers that be haven't denied things that have been happening in front of our own eyes.

Robinson

That's also true, you could make that consistent. But that effect of thinking like, But this doesn't make sense. Well, he cared a lot more about trying to work with the tools that he had, which were just comically limited. He had access to washed-up Hollywood actors, random drifter people. Bela Lugosi is dead by the time he's making Plan 9 from Outer Space. So he has to famously fill in the gaps with the footage. He has to use footage that he has that doesn't really fit the film or write the film around that footage and then get a guy to cover his face and pretend he's Bela Lugosi. But as I say, he's working with the tools he has.

Sloan

Absolutely. Plan 9 from Outer Space, of course, was funded with maybe $15,000 that belonged to various parishioners at the Baptist Church of Beverly Hills. He was able to hoodwink a bunch of nice old ladies at church out of their money. Last summer I was lucky enough that I was able to visit the studio where Plan 9 from Outer Space was shot, which, to any L.A. folks who might be listening, is behind Gold Diggers Bar on Santa Monica Boulevard. It's a music recording studio now, but it was the smallest, crappiest studio in Hollywood. It's incredibly small.

And if you see the cemetery set in Plan 9 from Outer Space, which is, I want to say, 20 feet wide and three feet deep. Basically, whatever you see in the frame, that's all there is. And so there will be all these scenes in Plan 9 from Outer Space of just people traversing the same two or three feet of set. I find that when I watch Plan 9, there's something about that cemetery set—the phrase "Lynchian" is overused, but I don't know what else to say. When I'm on that set, it's fake-looking, but I forget what reality looks like. I feel lost in that space that he's able to conjure.

Robinson

And so that makes his "bad movies" still bad if we're measuring in accordance with some specified level of technical skill, like, can you make the special effects convincing? And if you can't, can you make the dialogue sound natural? Or do you care about continuity? If you lay out a list of criteria like that, then, yes, these are not good films according to those criteria, but you point out that we don't have to adopt those criteria. Nothing makes us. And you say at one point the fact that Godzilla looks like a man in a suit doesn't matter. We accept that it can be a good film, even though it looks like a man in a suit. Tell me more about how you challenge the conception of these technical skills being used as our criteria for artistry.

Sloan

Well, yes. Who is dictating the terms of what constitutes a well-made movie? Who is in charge of that definition? You mentioned Godzilla. What would I rather watch? Would I rather watch Godzilla vs. Megalon, where the guy in the Godzilla suit slides across the landscape on his tail so that he could kick the other monster in the stomach—which, by any standard, does not conform to certain criteria of realism—or Jurassic World 3 or something? Who does it benefit if I say Jurassic World 3? There's big money invested in defining Jurassic World 3 as the ne plus ultra of a certain kind of standard of a well-made movie. When I look at those two images side by side, one lights up my imagination, and one just crushes it.

Getting back to Glen or Glenda, what it's saying, what it's trying to say, and the resources that it has to say it—is a well-behaved good liberal movie of the 1960s, like Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, a more interesting film than Glen or Glenda, which has just spit and shoe polish but is more complicated and full of ideas?

Or, okay, just one last example. I realize I'm being a little impressionistic talking here, but one of my favorite directors is Oscar Micheaux, who was the first great African American filmmaker. He made 30 or 40 movies in the '20s and '30s, and he obviously had no resources. He was a self-made man. He was an entrepreneur who was putting together these movies that were intended to speak directly to the Black experience as it was in America in the '20s and '30s. And of course, those movies have continuity errors. The acting is a little wobbly. They're flawed in a million ways, but of course they are. To focus on the ways that those movies don't reach certain industry standards is to overvalue those industry standards and the sorts of people who put those standards in place.

Robinson

Well, if we do that, we're almost saying that a low-budget movie is bad because it's low-budget. But then you're just measuring quality by wealth, and as good socialists, we don't want to do that. And you actually say that you don't think Ed Wood's films would have been better if he had a lot more money.

Sloan

Well, I think so, because I also think there's something in that Plan 9 from Outer Space cemetery that encourages a kind of collaboration with the audience. I feel myself using my imagination to sort of fill in the blanks of that cemetery. I think Bride of the Monster is the most money he ever had to make a movie. He had $70,000, which was not that much. Some disagree with me, but I find it a little less interesting than some of the other ones because it just reaches a kind of minimum standard of quality at times when it doesn't have the dreamlike quality. And in a Jurassic World, or a bad Star Wars sequel, or something like that, I sometimes feel that there's no room for the audience to kind of collaborate. There's no room for us to use our imaginations the way there is with some of these.

One of my favorite movies is a film noir from the '40s called Detour, which is a famously low-budget film. It's a really great movie. No apologies necessary for this one. But it was shot in Los Angeles, and there were some scenes in New York. They had no money to evoke New York, except there's a beautiful scene where two characters are walking along Central Park West, which is evoked with a fog machine and a street sign that says 57th Street or something like that. And it's powerful; it's beautiful. It's like a New York of memory.

Robinson

I watched The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari for the first time recently, and it's like, wow, look what you did with some bits of wood and light!

Sloan

I know. This is what gives me hope for the future of cinema. You actually don't need a lot of money to create an internally coherent and visionary world.

Robinson

You have a quote that I think is very provocative—at first, I was like, no, that can't be true—where you say, "I would take the worst Ed Wood film over all the films of Ron Howard." And I was thinking, wait a second, Ron Howard's made—what about American Graffiti? And I was like, no, wait, he was just in that. What did he actually make? I know he made Hillbilly Elegy.

Sloan

Maybe Apollo 13. Apollo 13 is pretty fun. But honestly, would you want to watch Apollo 13 right now? I don't think so.

Robinson

Defend this statement, though, because I think that is very provocative. Ron Howard is an acclaimed film director, and Ed Wood is considered the worst director of all time.

Sloan

You're not the first person to bring up that line, and I was being consciously reckless when I threw that in there. But I was making the statement kind of in the lineage of something that François Truffaut wrote back in the '50s. Truffaut was one of the first people to try to define the so-called auteur theory. He was making the case that the worst film by an auteur, somebody with a set of coherent esthetic, thematic, and intellectual preoccupations that run from film to film, is more interesting than the best film by a mere journeyman or a etteur en scène, as he said. And that's a position that has been oft argued over and is kind of hard to defend.

On the other hand, when I'm watching a lesser Ed Wood film like The Young Marrieds or Necromania, I'm seeing him pull at some of the same threads that he was pulling at in Glen or Glenda. I'm following him on this journey, this journey through his dark heart. I think with most of my favorite filmmakers, I just kind of like them. I like being in their company. I like being with their personality. And I don't feel that with Ron Howard.

Robinson

Yes. Ed Wood has a weirdness and a darkness to him, and that distinguishes him. I think people might think of putting him in the same category as the guy who made the infamous film The Room, Tommy Wiseau. The Room is known for its horrible dialogue and the fact that it's just a soup of clichés, and the acting is among the worst you'll ever see, etc. But Wiseau was a rich guy who self-financed this, and it's fun to laugh at this kind of thing. But what you argue is much more interesting.

Sloan

Well, and compared to Tommy Wiseau, who basically made one movie—he's done a couple of things since then, and the things that Wiseau has done since The Room, I think, have been paralyzed by his cult reputation. He knows there's a joke now, and he may not be in on it, but he knows there's a joke, and so he's playing to that joke. But Ed Wood, I think, was a compulsive creator. He just liked to make stuff.

Robinson

Eighty novels?

Sloan

Yes, something like that, and hundreds of short stories. And maybe a lot of those short stories and novels were written for money. But then also, he took pride in that work. He collected his novels; he wrote "from the personal library of Edward D. Wood Jr." on the first page of every novel. And you see him working through his strange preoccupations and all that stuff. Obviously, his film career slowed down later on, but he kept developing movies. He kept working in the industry in any way he could. He was making porn films, but by all accounts, on the sets of those porn films, he was in his element. He was having a great time. He had his megaphone. He was playing the part of a film director. So I admire him as a compulsive creator, as a relentless, undefeated artist.

Robinson

The subtitle of your book is "Made in Hollywood, USA", and one of the points that you make is that Ed Wood had to work within the film industry as it exists. He's living on the margins of this industry. And you might think much of this stuff is churned out for money. Well, yes, in the society that we have, which is not a socialist society, you have to do things for the money. You have to do schlock for the money, and you sneak in the interesting parts where you can. Glen or Glenda reflects that entirely, which is, okay, what is the film that I have to make for the money? And now, how do I get into the thing that I actually want to do?

Sloan

That's absolutely true. And you can see that especially in those novels he was writing, books like Diary of a Transvestite Hooker, which I don't think he was foolish enough to think that book was going to get him a Nobel Prize anytime soon. But you read that book, and this is his story. He's telling the story of him arriving in Hollywood through that book. Killer In Drag, Death of a Transvestite—you can see a theme that's running through some of these books. He is expressing himself. I think it's incredibly powerful that he embraced the medium that he was in.

Robinson

He does have a tragic end. The Tim Burton film is kind of a fantasy version of Ed Wood's life. It incorporates a lot of stories that are apocryphal. It has this ending where he ends up at a bar with Orson Welles, and they talk about the importance of staying true to yourself, or something like that. In the actual Ed Wood story, he dies fairly young as a broke alcoholic. It really is a tragic story. But as you point out, throughout that whole thing, he's just trying to keep creating by any means. Again, in the same way that Orson Welles was trying to do the same thing into the 1970s.

Sloan

It is a tragic story. And I feel like with the way the Ed Wood movie ends, it drifts off into fantasy. The encounter with Orson Welles, I think, heralds this because everybody watching the movie knows that this isn't real. This didn't actually happen, and there's a symbolic beauty in the worst director of all time meeting the best director of all time and having this meeting of the minds. But I think there's an acknowledgment in that drift off into fantasy on the part of Burton and his collaborators that we don't know how to tell the story from this point forward.

Ed Wood's descent into alcoholism, which killed him, is unambiguously tragic. It's unambiguously tragic that he was evicted from his last apartment and then died days later in the apartment of a friend, sleeping on the couch, basically, with his wife. What I find kind of beautiful and inspiring is that, when he was at his friend's place, he was like, So, are we still going to make that Bela Lugosi biopic together? He was still plotting. And I often wonder, what would have happened had he lived two more years, five more years, and had seen this new wave of "acclaim" that greeted him? I think he would have found a way to ride it. I think he would have found a way to try to make more stuff off that.

Robinson

Well, we're a good socialist magazine here, and I wonder how you would feel about the statement that what the late careers of both Ed Wood and Orson Welles have in common is an indictment of capitalism and a demonstration of how the economic system is the enemy of the true artist.

Sloan

I completely agree. And what I would add to that is what I find inspiring about both of them is that they were both down in the muck, and in their later years, did not acknowledge class hierarchies. And so you have an Orson Welles movie like The Other Side of the Wind. Peter Bogdanovich is in it, and he's the hottest director at the time. The cinematographer he's working with is Gary Graver, who made porn films. In fact, Gary Graver worked with Ed Wood, so they have that in common. There's one cinematographer who worked with both men, and I think that's powerful. It's like these two guys in the muck, embracing the muck, and not seeing any shame in it.

Robinson

Well, it's a totally fascinating life story. Your book is not just a biography but also a meditation on these fascinating films. And I did come out of it going, You know what? Fuck Ron Howard, I'll take Ed Wood.

Sloan

That's all I can ask. Thank you.

Robinson

I do hope that people will pick up Ed Wood: Made in Hollywood, USA. And I hope they will check out the films of Ed Wood. A lot of them are available for free. I just found Glen or Glenda and Plan 9 on YouTube.

Sloan

Talk about a socialist paradise.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.