The president has mastered the politics of “kayfabe,” where every conflict is a highly profitable spectacle.

In the pro wrestling world, one of the most important parts of the match typically happens outside of the ring and is known as the promo. An announcer with a mic, timid and small, stands there while the wrestler yells violent threats about what he’s going to do to his upcoming opponent, makes disparaging remarks about the host city, their rival’s appearance, and so on. The details don’t matter—the goal is to generate controversy and entice the viewer to buy tickets to the next staged combat. This is the most common and quick way to generate heat (attention). When you’re selling seats, no amount of audience animosity is bad business.

Once, the late “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, in his pre-WWE days, was wrestling for a regional promotion (National Wrestling Association) out of Southern California. The people that put the matches together, as well as the audience makeup, were majority-Latino, and Piper played the bad guy or heel. Playing that role allowed Piper to make many off-color racist remarks at the crowd and the Mexican wrestlers he faced. In reality, the man performing as Piper wasn’t racist, but it played well in making him a despised character, and people pay good money to see the bad guy get his comeuppance.

One night in the late-1970s, Piper, hoisting his signature bagpipes, told the crowd that he was sorry for all of his previous racist statements against the Latino community and wanted to apologize by playing the Mexican National Anthem. But Piper did not perform a Scottish rendition of “Mexicans at the Cry of War,” the actual anthem. Instead, he started to play “La Cucaracha” (the cockroach). The crowd exploded in anger: chairs went flying in the ring and Piper had to flee as the audience rushed the ring to assault him. The promoters were not worried for Piper’s safety, but thrilled by the audience reaction. Piper had generated so much heat, they knew that his name on a bill would be enough to sell out future matches. Political correctness be damned when you’re peddling tickets.

Nearly 50 years after Piper was run out of the arena, the Republican Party now employs the same theatrics once reserved for the ring, where scripted violence easily blurs into the real deal. Rowdy Roddy might not have expected a riot, but when Trump is the one implying that migrants are vermin—claiming they “pour into and infest our country”—he knows he is urging his audience to stand from their seats and pick up their folding chairs. Only this time, their target is not the man in the ring, but their fellow Americans.

More than ten years ago, when Donald Trump descended that golden escalator and announced his first campaign, he sounded like a wrestling promoter:

“THE U.S. HAS BECOME A DUMPING GROUND FOR EVERYBODY ELSE'S PROBLEMS … WHEN MEXICO SENDS ITS PEOPLE, THEY ARE NOT SENDING THEIR BEST…THEY’RE BRINGING DRUGS. THEY’RE BRINGING CRIME. THEY’RE RAPISTS. AND SOME OF THEM, I ASSUME, ARE GOOD PEOPLE.”

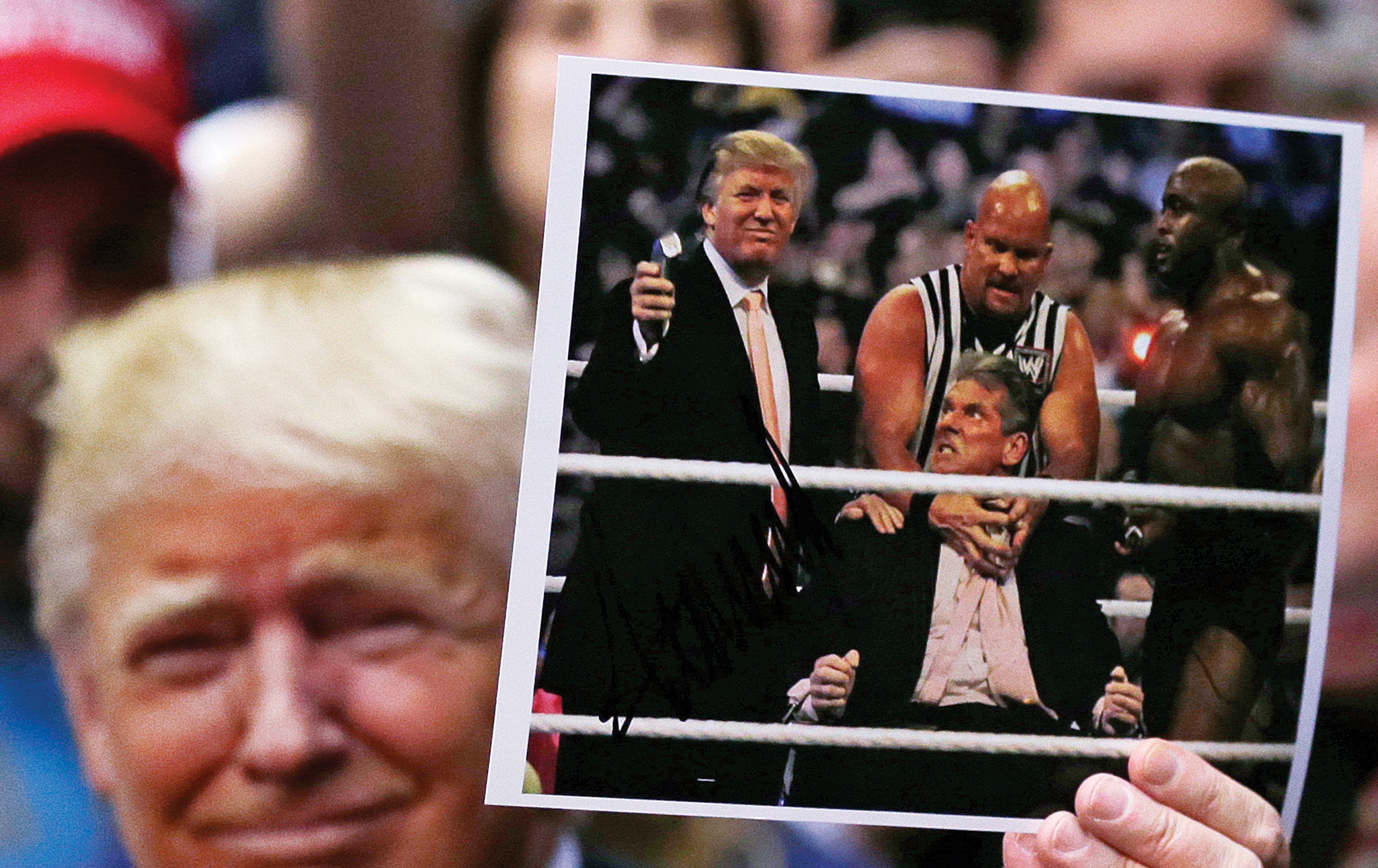

More specifically, Trump sounded like Vince McMahon, his personal friend and the co-founder of WWE. McMahon’s career as a carnival barker has followed a similar script as Trump’s; he inherited an empire from his wealthy father, ascended to fame in the 1980s, and has repeatedly avoided jail time for allegations of sexual abuse and hush money cover-ups. And when Trump set his sights on the presidency, McMahon and his wife Linda were there to help. Linda, the former CEO of WWE, “contributed a total of $7.2 million to two pro-Trump super PACs” during his 2016 run, and “the couple together donated more than $10 million to outside groups funding Trump’s race for the presidency,” according to 19th News.

Trump dominated the media cycle all the way up to his historic win in 2016, walking straight off a reality television set into the White House. Mainstream media, as well as independent left media, covered his every word, putting him at the center of all political discussion.

Trump’s onstage debut at the Republican National Convention in July 2016 even prompted this comment from Chuck Todd, the moderator of NBC’s Meet The Press:

CHUCK TODD: I don’t think I've seen that even on WWE.

DONALD TRUMP: Yeah, I know. Well, Vincent’s a good friend of mine. He called me. He said, “That was a very, very good entrance.”

Whether he was your villain or your new hope, everyone was wrapped in the kayfabe whirlwind that Trump would spin. Altogether, Trump’s bumbling narcissistic braggadocio netted him an estimated $2 billion in free media coverage for his 2016 campaign. CBS CEO Les Moonves said of Trump in the run up to his first election, “It may not be good for America, but it's damn good for CBS.”

Kayfabe is not limited to choreographed combat. It arises from the interplay of works (fully scripted events), shoots (unscripted or authentic moments), and angles (storyline devices engineered to advance a narrative). Heroes (babyfaces, or just faces) can at the drop of a dime turn heel (villain), and heels can likewise be rehabilitated into babyfaces as circumstances demand. The blood spilled is real, injuries often are, but even these unscripted outcomes are quickly woven back into the narrative machinery. In kayfabe, authenticity and contrivance are not opposites but mutually reinforcing components of a system designed to sustain attention, emotion, and belief.

In her 2023 book Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America, Abraham Josephine Riesman described a new form of this phenomenon, which she calls “neokayfabe.” She described the term to CNN:

After Vince made it a part of public record that wrestling was fake, that led to sort of the end of the illusion that wrestling was a legitimate, unplanned competition in the sporting realm.

Neokayfabe is when you operate not on the assumption of telling the audience, “Hey, everything you’re about to see is real.” You start by giving them the assumption, “Hey, everything you’re about to see is fake — except the parts that you think are real.”

It’s Trumpism. You’re left to kind of choose your own reality. So whether you are just taking it in and not trying to sort out what’s real, or whether you’re obsessively trying to sort it into true and false, you’re paying attention, and that’s all that matters.

This theater was in full motion during the 2016 election. Trump’s entire campaign was a massive work, where the twist was that the heel became the hero. His political opponent, Hillary Clinton, assumed she’d naturally be the babyface, but she and the Democratic Party cannibalized the one true hope of a Trump defeat, Bernie Sanders. It would be the kneecapping of the true face that would cement her role as a “bad guy.”

Once again, kayfabe is always in flux, and no role is static. Even Hulk Hogan, long celebrated as one of the most successful babyfaces in the history of professional wrestling, performed a world-shattering heel turn in the 1990s when he abandoned WWE for its ascendant rival, World Championship Wrestling. In the post–Cold War landscape, the nationalist and often explicitly racist gimmicks that once pitted Hogan against cartoonishly foreign enemies—like Soviet strongmen or the “terrorist” menaces embodied by characters like the Iron Sheik—no longer generated the heat they once had. The “Real American” had lost his draw. And when a hero stops selling tickets, the logic of kayfabe demands the unthinkable: turn him into a heel.

Trump, too, would eventually become a heel in the eyes of the public once again, during his attempt for a second term in 2020. His administration’s handling of COVID, the tax cuts for the wealthy, and a rise in white supremacist violence, especially coupled with high-profile police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, set the stage for what the audience assumed would be Trump’s final act: the January 6th insurrection.

After losing the election to Joe Biden, Trump quickly claimed that the election he lost was stolen through Democratic Party chicanery. Trump told his followers that he would “Stop the Steal” and a rally was held on January 6th where he urged the ravenous crowd “we are going to the Capitol” to prevent Congress from allowing Biden to become president. Trump himself would not join in the riot. He never intended to. It was all a work, one that would turn into a deadly shoot that cost the life of one his followers.

While Trump may be our first fully kayfabe president, his rise did not create the phenomenon. Kayfabe has seeped far beyond his wild rhetorical whims; it shapes the broader culture we all move through. We now live in a world where reality and fiction constantly blur, producing performances that feel like augmented reality made flesh. This is no longer something confined to the television screen. It structures how stories are told, how identities are sold, and how corporations craft narratives that feel “authentic” regardless of their truth. No examples capture this dynamic better than the tale of Richard Montañez.

“This guy should run for office if he’s that good at fooling everyone.” That’s a quote from former Frito-Lay executive Ken Laska about Richard Montañez, the man immortalized on film and in books as the custodian-turned-C-Suite-executive-creator of “Flamin’ Hot Cheetos.” The rags-to-riches story inspired the 2023 dramedy film “Flamin’ Hot,” and Montanez’s own autobiography, Flamin’ Hot: The Incredible True Story of One Man's Rise from Janitor to Top Executive. It’s an irresistible Horatio Alger-esque narrative, and that’s precisely the problem: it’s fiction.

Montañez did rise from janitor to executive, and helped develop products marketed to Latino consumers, but he did not invent Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. The snack was conceived years earlier by a team of white marketing executives responding to competitive pressure in the cheap, spicy snack market. The origin of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos has nothing to do with cultural authenticity—which Montañez stated was his inspiration—and everything to do with corporate strategy: flooding poor and working-class neighborhoods with ultra-processed, calorie-dense products. Montañez’s story, however false in its details, provided Frito-Lay something far more valuable than the truth; he became a human shield against scrutiny.

Through the lens of kayfabe, Montañez became the brownface of legitimacy, a performer whose presence made a predatory business model appear as racial uplift and opportunity. His lie works on multiple levels. It masks corporate exploitation while reinforcing the myth of meritocracy, the idea that the only thing separating a working-class custodian from the C-suite is timing, grit, and ingenuity. The narrative functioned perfectly, transforming structural inequality into a feel-good tale of individual triumph. Whether the story is true is beside the point; kayfabe demands an emotional buy-in, not factual accuracy.

As long as the crowd believes, the corporation's real goals remain invisible, the products keep flowing, and Montañez continues to cash in—books published, movies made, and motivational speeches delivered—long after the illusion has been exposed.

The Montañez lie works because it sells us the fantasy of a level playing field, a world where meritocracy isn’t a PR slogan but an economic law. By elevating Montañez as the high-school-dropout-turned-genius innovator, they got to plaster inner-city shelves with calorie-dense junk while positioning themselves as champions of multicultural innovation—less parasite and more patron saint.

The myth of the underdog triumphing through grit is one of the few cultural stories America still agrees on. Trump plays the same instrument with the same virtuosity. He knows that people want to believe that the system, rigged as it is, can be gamed on their behalf by someone who knows how the game is played. He consistently paints himself as an “outsider” who is “not a politician,” one who can run the country “like a business.” He tells crowds he’s going to “drain the swamp” because he’s familiar with every creature in it. But if that’s true, why would a man who has made his fortune in that very swamp suddenly turn against the friends and financiers who keep him in the rarefied air of the one percent?

It’s the same sleight of hand that lets us believe that a single man’s cultural heritage created a snack-food phenomenon while ignoring the corporate machinery behind it, along with the health consequences suffered by the very communities that snack was marketed to. And it’s the same sleight of hand that lets millions trust a billionaire with a long paper trail of unpaid contractors and shady deals to suddenly become the great protector of “the people.”

This isn’t just a “post-truth” society; that term is too soft, too academic. What Montañez and Trump demonstrate is how fully we’ve drifted into the universe of kayfabe, an ecosystem where the line between reality and performance is not blurred but irrelevant. A world of “alternative facts,” “fake news,” and engineered mythologies where truth is whatever keeps the crowd invested, outraged, inspired, or entertained. The story doesn’t have to be real; it only has to feel true. And as long as it does, the show goes on.

The visual culture of the new Trump-inspired right increasingly resembles the choreographed spectacle of professional wrestling. When Trump and the late Charlie Kirk’s widow, Erika, approached the stage at Kirk’s funeral, the scene was marked not by solemn entrance of sadness but by the bombacity of fireworks; an entrance more suited to WrestleMania than a memorial service.

Months earlier, Hulk Hogan had taken the stage at the Republican National Convention, torn off his shirt to a roar from the crowd, and bellowed “Let Trumpamania run wild, America!” as if endorsing a contender in a heavyweight title match. And when Trump survived two assassination attempts—one broadcast live as Secret Service agents pulled him from the stage while he raised a triumphant fist—some politicos speculated that the attacks could have been staged. But in kayfabe politics, the truth is irrelevant; what matters is how effectively the angle can be worked. Each incident became another narrative beat, another thunderous roar from the crowd, another surge in the polls that helped Trump soundly defeat his rival Kamala Harris. By the time the votes were counted, the WrestleManiafication of the Republican Party was complete.

Image: White House

The transformation was not merely aesthetic. It signaled a deeper shift in how the Republican Party understands power, conflict, and loyalty. The WrestleManiafication of American politics has allowed Donald Trump to become the ringmaster of the Republican Party, reshaping it in his own volatile image. The conservative movement no longer resembles a coalition of interest groups or ideological factions but an arena where Trump scripts the characters and decides the storylines. During his first term he begrudgingly relied on Washington insiders, people who at least recognized the boundaries of governance.

This time around he has no such constraints. He has staffed his circle with sycophants and outsiders—Linda McMahon (!), Elon Musk, Pete Hegseth, Robert Kennedy Jr., Kash Patel, Kristi Noem—people whose qualifications do not matter because qualifications are irrelevant in kayfabe politics. What matters is devotion. Trump once fought the establishment for control of the party; now he commands total allegiance and is attempting to convert the United States into Trumpland Inc., a personal fiefdom built on grievance, obedience, and the promise of revenge. He’s even planning to build a giant arena to host UFC fights on the White House lawn now.

Kayfabe may be a good strategy for winning elections, but it’s quite the opposite when attempting to govern. Trump may now be living in the shoot he worked himself into.

Trump returned to the same xenophobic immigration rhetoric that fueled his first rise, but this time the conditions made it far more effective: after his initial administration floated, and was blocked from, punishing Democratic “sanctuary cities” by bussing migrants into them, Republican governors like Ron DeSantis and Greg Abbott implemented the strategy at scale, overwhelming cities such as Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. This allowed Trump’s 2025 return to office to convert real municipal strain into political power through escalated ICE raids and mass deportations that functioned as pure kayfabe.

These spectacles of cruelty, unlike before, translated directly into policy thanks to loyalists embedded in the Supreme Court and ICE. But the visible cruelty of televised immigration raids has created negative effects for Trump 2.0. The public backlash has created fractures within Trump's own movement, with notable figures like Marjorie Taylor Greene, a once devoted acolyte, now denouncing his neo-fascistic policies, from expanded deportations to funding Israel’s war in Gaza and foreign aid for the Russia/Ukraine war, as a betrayal of “America First.” Greene has calculatingly positioned herself as a populist dissident despite her own role in enabling Trumpism. It’s a pivot that, alongside her announced retirement from Congress, suggests she may be preparing for higher office by adopting the same formula: wrap reactionary politics in faux-populist language, invoke a mythical past, and turn politics into theater.

In the film Idiocracy, the “president” of the dystopian future is a former wrestler: Dwayne Camacho, played by Terry Crews. He’s not merely a representative of the populace but an undifferentiated extension of it, a crude avatar of the lumpen culture he embodies. There is no delineation between executive authority and mass sensibility; the president casually calls the film’s protagonist “gay” for speaking in complete sentences.

Now, science fiction is not prophecy, but it is often a diagnosis of our present. Writer-director Mike Judge’s satire, meant as a caricature of the Bush era, now reads uncannily like a preview of the WrestleManiafication of the Republican Party under Trump. The collapse of decorum and the open contempt for expertise are no longer comedic exaggerations but governing principles. While talking to the press aboard the Air Force in November, Trump was asked by a reporter about releasing the classified Epstein files and responded, “Quiet, quiet piggy!” Instead of addressing the question of making the files public (something Trump campaigned on), he attacked the journalist’s question with the same belligerent anti-intellectualism Judge lampooned.

Trump didn’t just step into politics; he stepped into it the same way he stepped into the WWE: as someone who understands that the performance is the power, that the kayfabe is the product, and that the heel can win as long as the crowd stays engaged.

What Mike Judge imagines as dystopian absurdity—the merging of the presidency with the aesthetics of pro wrestling, is now the dominant grammar of Republican politics. Trump has blurred the line between character and man so completely that the crowd no longer demands a distinction. They tune in for the persona, so the persona becomes the man at the helm.

Richard Montañez and his Cheetos offered the country a feel-good myth about bootstrapping success and creative genius. Trump offered the country a grievance tale about cleansing a corrupt system he helped design. Both stories worked because they promised something the audience demands: simplicity, certainty, and a hero who appears to rise through grit and boldness. The fact that the details fall apart on close inspection is beside the point. Here, the performance becomes the evidence. Credibility comes not from expertise but from the force of the reaction you can produce.

This is why Trump flourishes in the ruins of the old era of credentialed professionalism. The Obama years were the peak of a technocratic faith in experts, fact checking, and managerial competence. There was a time, not too long ago on the internet, where people spent their evenings learning about logical fallacies and reading policy explainers. Trump rose alongside the expansion of low culture in the 1990s, the world of the Jerry Springer Show, shock jocks, pro wrestling, and reality TV confessionals. When he tested a presidential run in 1999 and told Larry King that Oprah would be an ideal running mate, he was signaling something real: celebrity works as political capital, and public authority can easily be produced through spectacle rather than knowledge.

Kayfabe does not abide ideological rigidity. It mutates and adapts itself according to whatever keeps the crowd invested. Trump doesn’t simply employ kayfabe; he extends it, pushing it toward a place where politics is a form of traveling performance art. The incentive is never to address problems. The incentive is to stage them louder, build them bigger, and center yourself inside them.

In this world, Trump functions as both conductor and creature of his very own made-for-TV special. He directs it and he is shaped by it. This leaves the country with a pressing question: can a democratic system survive when spectacle becomes its main operating condition? If kayfabe has consumed the political imagination so completely, the only response that matters will not come from fact checking, moral appeals, or longing for professionalism. The only force that will break it is material improvement, because only real gains cut through performance by changing the experience itself.

During a recent press conference with Zohran Mamdani, a reporter asked the New York mayor-elect whether he still believed Trump was a fascist. Before Mamdani could deliver his careful, measured response, Trump grabbed his arm and laughed, “Just tell them yes, it’s fine.” In that moment he revealed the core truth of the era: accusations do not matter because words do not matter. This is the same man who survived an election after bragging on tape about sexually assaulting women. In kayfabe politics, scandal is far from a liability; it is content.

If someone like Zohran Mamdani can use even the compromised proximity of Trump’s spectacle to deliver material gains for New Yorkers, then the gravitational pull of that charade begins to weaken. Trump’s singular power lies in his ability to center himself in every conversation, to make himself the mirror the country is forced to look into. Like the jealous queen in Snow White, he asks again and again who is the fairest of them all—but his mirror is the camera, and the endless abyss of online coverage is what keeps his performance alive.

Yet despite building his entire political empire on kayfabe, Trump doesn’t seem to quite grasp its limits. In an October 2024 podcast interview with “The Undertaker,” Trump asked the pro-wrestler a telling question—one that implies he still doesn’t quite understand where the show ends and reality begins:

TRUMP: How often did it happen where you’re fighting somebody, and you made a mistake, and he gets angry and he really goes at you? […] And what would happen? The guys would run into the ring and stop it, right? I was told when you had a lot of guys running into the ring, that meant you had a problem.

UNDERTAKER: Usually when that happens, it’s part of the show.

TRUMP: So what stops somebody from going nuts? And you know, really starting a real fight?

UNDERTAKER: Probably losing their job.

Kayfabe only works when its orchestrator is in control. It only exists if the audience is still watching. The challenge of the coming years is not simply defeating Trump at the ballot box, but starving the spectacle itself. Only when results speak louder than the performance will the era of kayfabe politics finally begin to crack.