Abolish the Texas Rangers

They might be portrayed as heroes in movies, but the Rangers have a long, ugly history of white supremacist violence.

Under the false pretense of a migrant “invasion,” the Trump administration has waged asymmetrical warfare on America’s immigrants, yielding shocking and depressing results. Just to name a few: since Trump’s inauguration the United States has functionally disappeared scores of permanent residents, including rendition to CECOT, a Salvadoran concentration camp; detained individuals at Guantánamo, America’s most infamous torture center; and deported multiple U.S. citizens, including several children. And just like its federal counterpart, Texas is sending masses of law enforcement officers to surveil, profile, and collectively punish thousands on the basis of their putative national origin. But long before President Trump proclaimed that “hordes” of migrants were “invading” the United States, Texas Governor Greg Abbott declared that they had invaded the Lone Star State first. Abbott has been at this a while: in 2021, he declared “illegal migration” an official disaster in 34 Texas counties. To deter those seeking refuge, Texas laid miles of barbed wire, placed razored buoys, and deployed gunboats in the Rio Grande to booby-trap the riverine border with Mexico.

Both Trump and Abbott’s claims of an “invasion” are legally meritless, factually inaccurate, and can best be categorized as cruel political farce. What fascinates is not the declaration itself—a hackneyed trope echoing the racist “great replacement” conspiracy theory—but rather Abbott’s justification. Abbott alleges that Texas and its dignitaries are the “inheritors of a responsibility first recognized by our brave ancestors more than 235 years ago” to “defend our state, and this nation, from grievous threats to our border.” To start with the obvious, 235 years ago there was no state of Texas. Depending on whom you ask, the region was either a constellation of sovereign indigenous land or a territory owned by Spain, soon to be Mexico, and it would continue to be Mexico for many decades thereafter (including the Mexican state Coahuila y Tejas).

As Gerald Horne would argue, Texas was, and remains today, an emblem of a regressive, punitive, and counterrevolutionary republic. Abbott’s reference to an inherited responsibility of yore is not just some wistful citation: the state today does much of what it did back then. What is most revealing about modern-day Texas is not just what it has decided to “defend,” but whom it has endowed with the authority to do so—and the extent of their bloody legacy.

In the United States’ early years there was hardly a border and even less of a “border patrol”; it was simply the Wild West. Colonizer Stephen F. Austin sought to change that, arriving in Texas shortly after Mexico liberated itself from Spanish control in 1821. To protect the proprietary interests of white settlers from thieves, bandits, Native Americans, and virtually anyone else, Austin founded the Texas Rangers as an ad-hoc force of ten men in 1823. These original Rangers inspired the eventual creation of the Border Patrol; many of the first Border Patrol agents were direct Ranger recruits and brought with them their violent tactics. The Texas Rangers have been lionized in the American cultural zeitgeist ever since. They are usually displayed stoically, carrying a Colt .45 pistol and adorned with a ten-gallon hat. Novels, movies, and TV shows such as Walker, Texas Ranger, The Lone Ranger, and Laredo portrayed them as valiant rogues patrolling the vast and desolate Texas brush. Who tracked down and killed the outlaws Bonnie and Clyde in 1934? Texas Ranger Frank Hamer. Which mascot did the Washington Senators major league baseball team pick when they moved to Texas in 1972? The Rangers, of course. Whose bronze statue greeted you at the Dallas Airport until its removal in 2020? None other than Texas Ranger E.J. Banks. Even rapper DaBaby released “Walker Texas Ranger” which—in 2018—was arguably considered a bop.

The mystique of the Rangers as a legitimate law enforcement outfit necessary to combat the dangers of unsettled land still permeates American culture. Back in the 1800s, Texas really was the Wild West. As Cormac McCarthy wrote in Blood Meridian, out there “beyond men’s judgments all covenants were brittle.” The novel is inspired by firsthand accounts of the Glanton gang—a sadistic group of scalp-hunters who roamed the U.S.-Mexico borderlands in the mid-19th century, led by the notorious Texas Ranger John Joel Glanton. Like Glanton’s crew, the Rangers’ initial mission was simple: to ethnically cleanse Texas of Comanche, Karankawa, Cherokee, Wichita, Caddo and all other Native peoples in the area. A fun fact: the name “Texas” derives from Tejas, the Indigenous Caddo term for “friend,” which surely came as a surprise when the Rangers came to visit. (Austin declared proudly that “there will be no way of subduing them[...] but extermination”).

According to historian Doug Swanson’s essential text, Cult of Glory, the Rangers’ own accounts portray Glanton and his gang—filled with ex-Rangers—as responsible for the massacre of hundreds of Apache Indians, scalping them for ransom and gambling away the proceeds. They continued to drive Indigenous people from their homelands during the Cherokee War in 1839, as well as the Council House Fight and Battle of Plum Creek against the Comanches in 1840. After a decade of unbridled vigilantism, Texas’ provisional government formally established the outfit in 1835 to provide “a safeguard to our hitherto unprotected frontier inhabitants.”

The Rangers’ job thereafter was to protect Texas for white settlers, a mission that is best understood with reference to contemporary local geopolitics. Texas at the time was, after all, still Tejas: which is to say, Mexico. And Mexico, under President Vicente Guerrero—himself of African descent—had outlawed slavery, an extremely inconvenient fact to Texas’ feverishly racist brass. To them, forcibly seizing land, having slaves cultivate it, and lavishing in the profits was the sine qua non of Texas’ manifest destiny. Remember the Alamo? Historians do, and have concluded that Texas’ declaration of war that presaged the Texas Revolution was fought to vindicate this right to own human beings. Look no further than its Constitution: “all persons of color, who were slaves for life previous to their emigration to Texas, and who are now held in bondage, shall remain in the like state of servitude, provided the said slave shall be the bona fide property of the person so holding said slave.”

By the end of 1836 about 40,000 white settlers moved to Texas, the majority of whom were slaveowners, and they found immediate protection from the Rangers. If the settlers didn’t haul enough slaves with them, or they were uninterested in importing new ones at Galveston, all they needed to do was call the Rangers, who were happy to go out of their way to assist. There are countless reports of escaped slaves who hoped to cross the Rio Grande to freedom in Mexico but were ensnared by Ranger violence. They frequently broke the international neutrality laws that forbade their trips across the border and, as Greg Grandin notes in his book The End of the Myth, Texas ended up becoming “the last stop on an underground railroad running in reverse: slavers kidnapped freedmen and women from [Mexico] and re-enslaved them in Texas.” Perhaps the ugliest example of re-enslavement came in 1855, when 89 Texas Rangers, led by James Hughes Callahan, terrorized scores of the Lipan Apache and torched the town of Piedras Negras to the ground. As if state-sponsored mass arson wasn’t sufficient, Texas historians regard the Callahan Expedition as subterfuge for the retrieval of self-manumitted former slaves during a long period of state-sponsored bounty hunting.

The U.S. seized nearly half of Mexico in the Mexican-American War, including Texas. This afforded the Rangers the legal cover to continue to ethnically cleanse the borderlands, this time as the protectors of systematic settler-colonial land theft. At the Texas government’s behest, the Rangers helped rid Texas not just of Indians, but of Mexicans, whom one Ranger quipped were as “black as n—rs[…] and ten times as treacherous.” Though the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo set out that “property of every kind, now belonging to Mexicans[...] shall be inviolably respected,” white settlers paid that little mind and engaged in dispossession of Tejano land. The Rangers, in cooperation with land speculators, came into small villages and seized local lands, sometimes accompanying a bill of sale with a pointed handgun. As David Montejano reported in his book, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, many saw the same message posted to their properties: “If you are found here in the next five days you will be dead.” Many were indeed found dead at the hands of the Rangers, the rest rendered titleless tenants or forced laborers under peonage and vagrancy laws.

The 1877 El Paso Salt War is an emblematic example from the era. Settlers poured into West Texas without any regard for local customs, including the historic tradition of communal property at the famous San Elizario salt beds, which allowed a local community to delight in a scarce and essential resource. Charles H. Howard, himself a recent settler, objected to the notion of a shared lot and attempted to claim it all for himself. He even orchestrated the arrest of two Mexican Americans for admitting to taking salt without paying. When a popular local politician intervened on the locals’ behalf, Howard shot him to death. Though Howard fled, he returned shortly thereafter under the protection of a company of Rangers who, instead of prosecuting Howard for a political assassination, accompanied him to stop locals from retrieving more salt. Tensions flared, a riot broke out, and a popular army of about 500 ethnic Mexican and Tejano inhabitants outmaneuvered two dozen Texas Rangers, resulting in one of the few known reports of Ranger surrender.

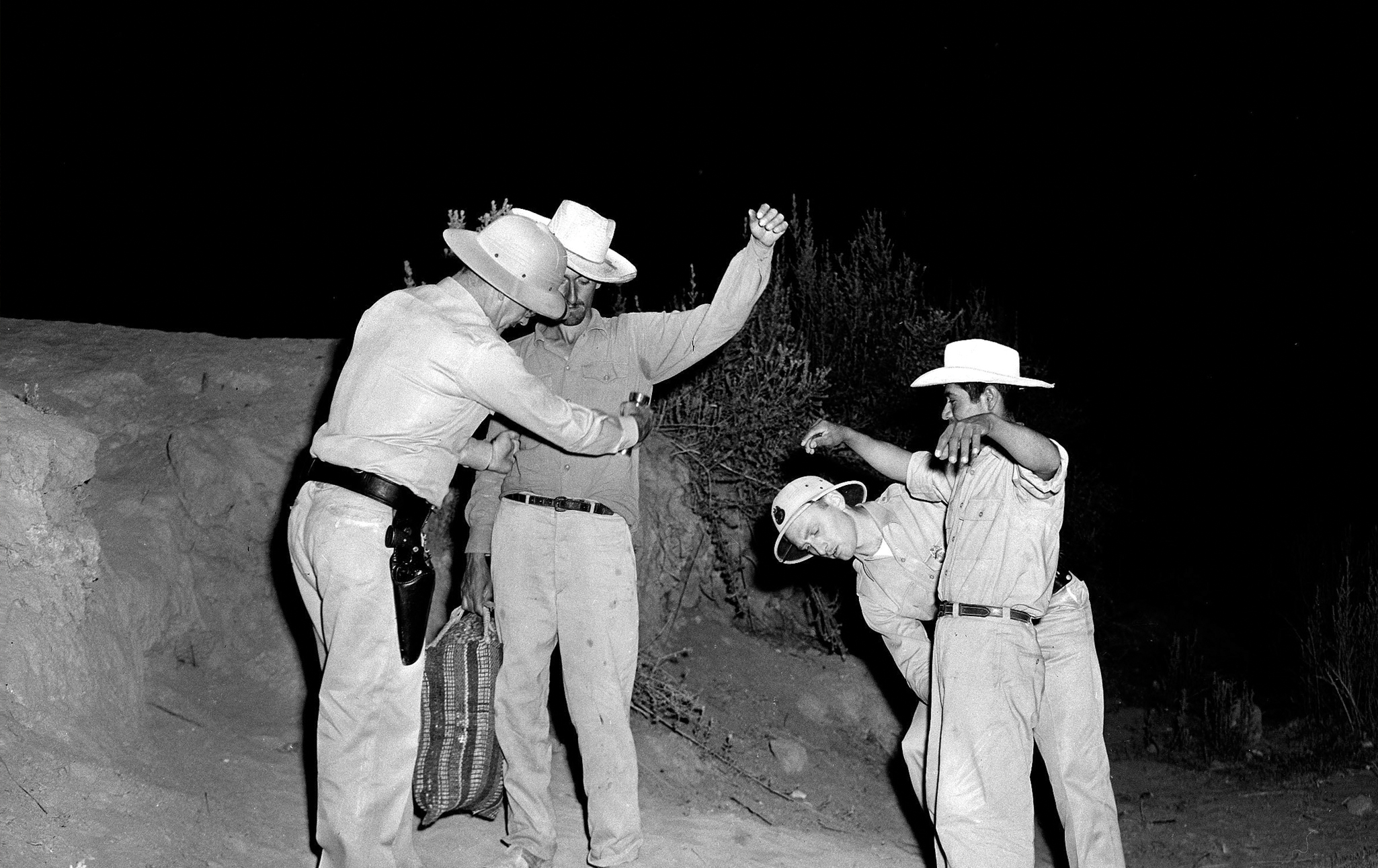

The Rangers were hardly deterred. At the turn of the 20th century, the events leading up to the Mexican Revolution forced many displaced Mexicans to seek safe haven northwards. The Rangers, charged with clearing the borderlands for white settlement, became participants in an all-out South and West Texas race war, now known as La Hora de Sangre (“The Time of Blood”). Historians have meticulously documented this Ranger violence in “Refusing to Forget,” an essential project shedding light on “some of the worst racial violence in United States history.” Many historians “estimate the number of such victims [between 1910 and 1920] to be as low as 500 and as high as 5,000.” The terror reached a crescendo during 1915-1916, a period referred to as La Matanza (the massacre), in which “approximately 300 ethnic Mexicans were murdered, either shot on the run, execution-style, or lynched.” The 1918 Porvernir Massacre was perhaps the cruelest moment of the Juan Crow era and saw a handful of Rangers, accompanied by U.S. cavalrymen, ride out to the small border town of Porvenir, round up 15 boys and old men, line them against a wall, and execute them one-by-one. As a local schoolteacher remarked, “the Rangers made 42 orphans that night.”

But if you ask the modern-day Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS), they seem to view the Rangers’ extensive list of massacres in a different light. According to the history section of the agency’s website, the “Texas Rangers played an effective, valiant, and honorable role throughout the early troubled years of Texas[...] [holding] a place somewhere between that of an army and a police force.” The reality is that the Rangers served as a white supremacist gestapo. During a 1919 congressional investigation into the Rangers’ violence, Texas Representative Claude B. Hudspeth testified at the State Capitol that “good citizens” feared that their country would be uninhabitable without Ranger brutality: “You have got to kill those Mexicans when you find them,” he said, “or they will kill you.” (Texas rewarded Hudspeth’s moral clarity with an eponymous 4,500-square-mile county.)

That testimony allowed the Rangers to escape criminal charges from murder to intimidation during the Canales Investigation, named after José Tomás Canales: the only Latino state lawmaker in Texas for many years and someone who sought to end Ranger terror in the state. A congressional investigation of the Porvenir massacre and other violence by the Rangers lasted weeks, resulting in a 1,600-page report chock-full of evidence of their brutality. But no one was ever prosecuted, and it was very rare for any Ranger to be charged at all with killing a Mexican or African-American. Hudspeth would go on to help found the U.S. Border Patrol in 1924, handing off the responsibilities of terrorizing a migrant population to a willing federal government. The agents oversaw an exponential increase in the deportation of Mexican immigrants across the southern border, from under 2,000 in 1925 to more than 15,000 in 1929. As Grandin notes in his book, two Border Patrol members, new recruits from the Rangers, “were accused of tying the feet of migrants together and dragging them in and out of a river until they confessed to having entered the country illegally.”

The investigation into the Rangers’ extrajudicial executions forced them to pivot to more covert means of oppression, paying particular attention to the burgeoning Tejano labor movement. As the 20th century unfolded, the Rangers obstructed union membership wherever possible, raiding Industrial Workers of the World offices and breaking up strikes of all kinds: railroad strikes, longshoremen’s strikes, and in an affront to Texans everywhere, even a cowboy strike. The Melon Strike is perhaps the Rangers most’ infamous example, in which Tejano farmworkers—including children—worked in subhuman conditions for wages as low as $0.50/hour. The farmworkers allied with legendary labor leaders Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta and refused to harvest the 1967 melon crop in Starr County, Texas until they received basic protections like potable drinking water, sanitation facilities, and electricity. The Rangers responded by threatening and beating union leaders, leaving one worker confined to a wheelchair with a permanently curved spine. The brutality reached the United States Supreme Court, which concluded in 1974 that the Rangers’ anti-union activities displayed a “prevailing pattern” of violence, intimidation, and coercion.

Texas consolidated the Rangers into the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) in 1935, and over time they evolved into a more traditional state law enforcement entity, the Texas Ranger Division. The modern-day Rangers have thrust themselves into the spotlight for largely the same reasons as the legacy Rangers: engaging in unlawful activity and violence along the Texas borderlands. The Rangers have officially patrolled the border since at least 2009, when then-Governor Rick Perry announced that Texas was introducing Texas Ranger Reconnaissance Teams to investigate transnational crime. This spawned a minor international incident in 2010 when the Rangers, flying high-tech planes across the border, “admitt[ed] to spying on Mexico.” (Texas officials in fact recently testified that they still do this). The Rangers hardly stopped there, venturing into territories to seize land for which they had no deed, including leading multiple operations to secure deserted islands in the Rio Grande, likely in violation of at least one riparian boundary treaty, if not more. When they are not engaging in international espionage or land theft—something the Rangers did at the U.S. Army’s behest during the Mexican-American War—the Rangers have had time to assist private vigilantes and anti-migrant militias with things like background checks of their members.

Governor Abbott expanded the Rangers’ job description in 2021 with the launch of Operation Lone Star, an attempt to wrest away federal authority for immigration and border enforcement into Texas’ hands. It is a vast anti-immigration initiative that is perhaps best understood if you think of it as being launched one hundred years before, in 1921, when Texas’ aggressive, unorthodox, and punitive methods for border enforcement contributed to the need for permanent federal oversight and control. (It is no coincidence that Texas’ response to the humanitarian demands imposed by the Mexican Revolution was to increase the Rangers’ annual budget and inflate the company from about two dozen officers to around 1,350). Under Lone Star, Abbott charged the Rangers to “lead the department’s border security program with a mission to deter, detect and interdict criminal activity across the Texas/Mexico border . . . [providing] direct support to the U.S. Border Patrol.” The program has dual and interrelated aims: (1) to stop noncitizens from entering Texas, and (2) to kick out anyone that already got in.

To address (1), Governor Abbott deployed the Texas National Guard and DPS troopers to install 18 miles of concertina wire along the border, a 1,000-foot buoy barrier in the middle of the Rio Grande, and deploy military vehicles including a boat blockade. Despite the clear evidence that many people attempting to cross the Rio Grande were asylum seekers hoping to obtain an asylum interview—a right protected by federal and international law—a DPS official said that the razor wire and buoy barriers helped “save lives.” In July 2023, the Houston Chronicle published a devastating account of Abbott’s initiative, including instructing officers to push children into the Rio Grande, identifying a 19-year-old woman stuck in razor wire having a miscarriage, denying water to migrants in extreme heat, and simply watching a man rescue his child who got stuck on a serrated buoy. In January 2024, a woman and two children drowned trying to cross the border at Eagle Pass, while Mexican authorities rescued two others. The situation is hardly any better inland. Indeed, the bones of those seeking refuge and safety are still scattered throughout the Texas brush.

According to Border Patrol estimates, approximately 250 to 500 migrants die each year migrating through the southwestern United States. Since Operation Lone Star, these numbers have skyrocketed: at the end of the 2022 fiscal year, Border Patrol reported finding 651 bodies at the Texas-Mexico portion of the border alone. According to an investigation by the Texas Tribune and Source New Mexico, when El Paso County joined Operation Lone Star, it became the deadliest place along the entire U.S.-Mexico border. (Del Rio, Texas was the second.) As was the case during La Hora de Sangre, it is not uncommon to find skulls eroding away in the Texas brush. From January 2023 to August 2024, 299 human remains were reported in the El Paso sector, the most of any sector along the southern border, more than double the number of cases reported during the 20 months prior, and the largest count in the past 25 years.

President Trump’s ascent to the presidency was a boon to Operation Lone Star’s second aim: deporting noncitizens. Texas hardly needed any help, having already introduced a criminal trespass system, the purpose of which the ACLU observed is “crystal clear[:]... to deter migration and punish migrants for coming to the United States.” The program operates under an entirely separate criminal prosecution and detention system—so while lawyers for some migrants arrested under this mandate have called the operation “a shadow legal system rife with problems,” some refer to it by a more accurate term: apartheid. Abbott signed SB4 into law in December 2023, making it a state crime to cross from Mexico into Texas without permission, and authorizing Texas officials to deport those convicted wherever possible. Taken together, these acts have empowered Rangers and other DPS officers to arrest tens of thousands of migrants on misdemeanor charges of trespassing. The program “show[s] clear indications of profiling based on race and national origin” and, one year into the program, 98 percent of the individuals arrested were Latino. In 2022, a Texas judge ruled that the DPS had engaged in unconstitutional sex discrimination in its enforcement of anti-trespassing laws due to the almost exclusive surveillance and arrest of men. As the ACLU concluded in its report, Texas has spent “billions of dollars to racially profile and arrest people who pose no threat to public safety, then forces them into a separate and unequal legal system run by the state.”

Trump’s inauguration put this directive into overdrive. In 2025, Governor Abbott directed the DPS to activate “tactical strike teams,” including Texas Rangers, to ramp up Operation Lone Star, this time working with federal officials to “identify and arrest the nearly 5,400 illegal immigrants with active warrants from local jurisdictions across Texas.” Having already beaten Trump to the punch to label the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua a “foreign terrorist organization,” Abbott’s brownshirts were able to spring quickly into action. Under SB4, the Rangers and other Texas officers can question and arrest anyone they suspect of entering Texas through Mexico without legal immigration status—which is to say that they can likely arrest anyone Latino at any time.

Perhaps this explains why Texas recently arrested and deported to CECOT Pedro Luis Salazar-Cuervo, a Venezuelan man with no criminal record whom they accused of Tren de Aragua membership. Texas had a slight problem: there was no evidence to substantiate this claim, so instead Texas used a single photo of Salazar-Cuervo beside another man who happened to have tattoos. A fundamental problem with such guilt-by-association is that tattoos are not indicative of membership in any Venezuelan gang, let alone Tren de Aragua, because gang tattoos are a Central American phenomenon, not South American. More importantly, it wasn’t even his tattoo. But facts matter less to Texas than the mandates of Operation Lone Star. To Governor Abbott, intra-hemispheric migration is a scourge on Texan society, a harbinger of barbarism to be avoided at all costs. It is no wonder he dispatched the Rangers to police immigration, given that their founding charge in 1835 was to “prevent the depredations of [...] savage hordes that infest our borders.”

If you closed your eyes and imagined a Texas Ranger, you very well might envision someone like E.J. Banks, whose statue was a decades-long mainstay at Dallas’ Love Field Airport. He was cast 12 feet high in bronze, standing gallantly with a holstered pistol and cowboy hat. He was not depicted, however, in his true stripes: a more accurate portrayal would have seen him protecting a white mob, next to their effigy of a lynched Black student, to prevent Black students from desegregating Texas’ Mansfield High School in 1956. At the time, the town of Mansfield was on the precipice of a full-blown race riot, as local citizens hung not one but two effigies; the one on Mansfield’s Main Street read: “This negro tried to enter a white school.” Banks heroically protected the white mob from the terrors of desegregation in Mansfield, providing cover for rock hurlers and epithet throwers as he did at a similar riot later that year at Texarkana Junior College. No Black students matriculated at either school that year.

George Floyd’s murder in 2020 forced the United States to reckon with its obsessive idolatry of law enforcement, leading to the removal and destruction of statues across the country, including that of Ranger Banks. It is unclear if any further reckoning will occur, as each passing year sees the Rangers endowed with greater responsibility over Texas affairs (and, in fact, Ranger Banks himself is proudly enshrined in the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame in Waco). Although a Texas judge declared the Rangers unconstitutional in 1925, lawmakers eventually drafted and passed legislation making it illegal ever to abolish the company. As Doug Swanson observed in his 2020 book Cult of Glory, the Rangers covered up their wrongdoing through the art of “mythic rehabilitation and resurrection.” “For decades,” Swanson continued, the Rangers “operated a fable factory through which many of their greatest defeats, worst embarrassments, and darkest moments were recast as grand triumphs. They didn’t merely whitewash the truth. They destroyed it.”

At the Rangers’ bicentennial in 2023, Abbott tweeted: “From the Old West to modern day Texas, the Lone Star State would not be the place it is today without the bravery and service of the Texas Rangers.” He is at least partially right. Texas commanded the Rangers to etch their own history in America’s annals; they were trailblazers in a country that delighted in the example they set. The Texan Indian raids presaged what would become the systematic extermination and displacement of our indigenous peoples. The re-enslavement of freed Black people in Mexico came long after the federal 1807 Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves. The expropriation of Tejano land was a paradigmatic example of the unrepentant westward conquest in the U.S., as was the Salt War for extractive gain and private enrichment. Perhaps no example is more illustrative than the outright murder, banishment, and imprisonment of migrants who fled the terrors of the Mexican Revolution, conducted at the hands of the Rangers, many of whom went on to found the first Border Patrol. So it should come as no surprise that Governor Abbott’s unrestrained and indiscriminate mission to round up and deport migrants, either through violent means or with violent ends, was a harbinger for President Trump’s agenda. In fact, it is completely legitimate to conclude that Texas is doing the federal government’s bidding, given that Texas asked for—and appears ready to receive—$12 billion to reimburse the state for border security spending.

The “grievous threat” to the Texas border that Abbott inherited from over “235 years ago” was, as it turns out, largely just attempts by nonwhite people to migrate to land upon which white people had laid a claim. If Stephen F. Austin composed the score for Texas’s manifest destiny, then Greg Abbott is the lead singer of Manifest Destiny’s Child. Never mind that migration is gaining traction in the United Nations as a human right. To Texas, and the United States too, migration is tantamount to a declaration of war by a bellicose enemy. It is for that reason that Texas engages in gunboat diplomacy and dispatches the Rangers—historically one of the nation’s most violent law enforcement entities—to protect Texas here and now from another “mass invasion.” Notwithstanding the ten separate incursions the U.S. military has made into Mexico, let alone the relentless Ranger conquests across the border (many Rangers accompanied William Walker on his infamous quest to colonize Nicaragua), it is Texas that is being invaded, it is Texas that must clear its land for white prosperity, and it is the Rangers who will provide the legal cover to do so. Reached for comment in a 2024 radio interview, Abbott claimed: “[t]he only thing that we’re not doing is we’re not shooting people who come across the border, because of course, the Biden administration would charge us with murder.”

It should thus surprise few to recall that the 2019 El Paso Wal-Mart shooter, who murdered 23 mostly Mexican or Mexican-Americans in cold-blood, stated in his manifesto that: “[t]his attack is a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas. They are the instigators, not me. I am simply defending my country from cultural and ethnic replacement brought on by the invasion.”