Caring About Your Principles Versus Caring About Power

When should you “break eggs to make an omelette”? Which eggs? How many?

One of the most difficult questions in all of politics is the means/ends dilemma. You are, presumably, a person with a particular set of values that you would like to see enacted in the world. But if you’re actually interested in advancing your cause, it is impossible to be an absolutist about everything, and so you must make various unpleasant compromises with Reality, which often stubbornly refuses to conform to your expectations.

Anybody serious admits that all political action requires a balance of principle and practicality. The tougher questions are: how do you know which compromises are betrayals of your values? When do you stand firm and when do you bend a little? At what point have you made so many compromises that you no longer have a principle at all? Without a clear notion of how these questions ought to be answered, disaster can ensue. One important lesson of the bloodiest historical revolutions is that if you wave away means/ends questions with “You can’t break an omelette without breaking a few eggs,” you might end up with a lot of broken eggs and no omelette to show for it. (And of course, the eggs are actually people.)

In liberal/left/progressive politics, this argument is constantly raging between more centrist types and leftier types. The centrists call the lefty types utopians unwilling to reckon with Political Reality. The lefty types say the centrists have failed to stand for anything and have sold out progressive values. My sympathies on this are largely with the lefty types, for a simple reason: there is actually a pragmatic value to being strongly committed to your principles, and the short-term gains you get from compromises can blind you to the fact that you are slowly straying from your vision. I am also, of course, constantly wary of the risk of becoming Lenin: thinking that whatever is done in the name of the revolution is just. (That’s almost a direct quote from him, by the way. Lenin once told a woman that “In order to take power, every means must be used.” When she replied “Even dishonest ones?” Lenin said “Everything that is done in the interests of the proletarian cause is honest.”)

A good lesson in what can happen when you prioritize strategy too much over principle can be seen in Bill Clinton’s brand of politics. In 1992, Clinton’s New Democrats reasoned that the American public was being turned off by liberal policies. They therefore courted so-called Reagan Democrats by adopting more conservative rhetoric on a number of issues: Clinton campaigned on a “tough on crime” and anti-welfare platform. (One Clinton advisor said he was surprised by this approach, because it wasn’t something Democrats ever did.) Clinton even went so far as to directly pander to the fears and prejudices of racist voters. It worked, of course: Clinton was phenomenally politically successful. But it’s also a peculiar strategy: sure, the easiest way for a Democrat to get into office is to adopt half of the Republican platform. All the Democrats will still have to vote for you because you’re the lesser evil, but you might also peel off some Republican voters. Strategically, it’s easy to see why this move can be smart. The only trouble is that it’s completely unprincipled. Presumably, if you’re a Democrat, you’re horrified by most of the Republican platform. Adopting pieces of it just because it gets you into office erodes the entire justification for your seeking that office to begin with: you were trying to do good, not seek power for its own sake. (Right? Right?)

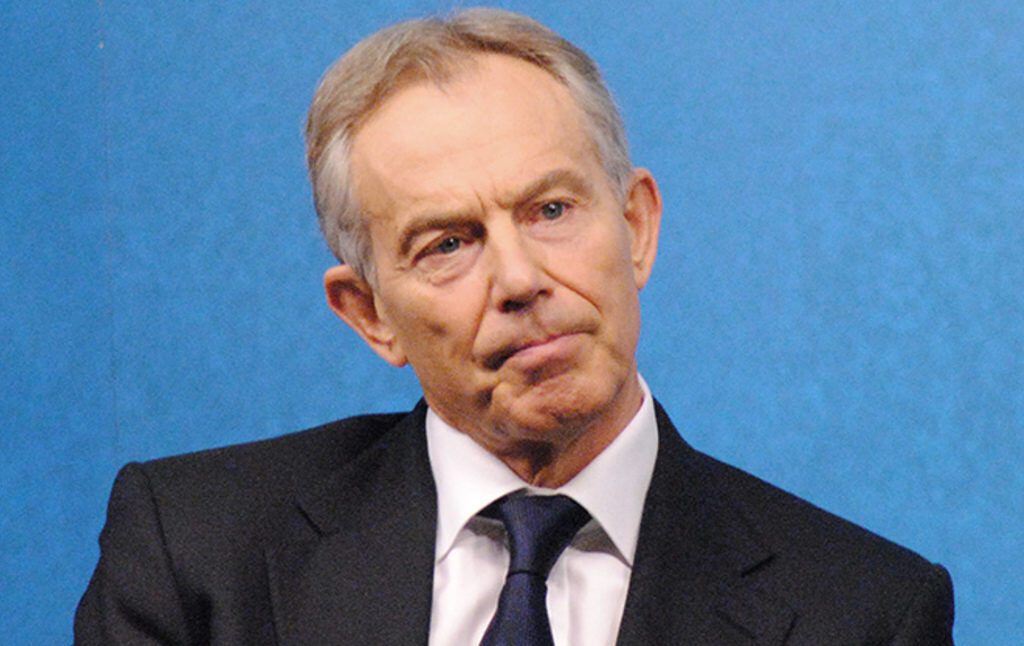

This debate is currently happening again in the U.K. The Labour Party there is doing unexpectedly well under the leadership of a radical socialist, Jeremy Corbyn. They are consistently polling ahead of the current Conservative government, which is in shambles. But centrist former Prime Minister Tony Blair, who detests Corbyn, has said that Labour’s success is misleading: if they didn’t have a radical leader, they would be doing even better in the polls. Blair says that Labour is not popular because of Corbyn, but despite him, and that a centrist Labour Party would have an even greater advantage against the Conservatives.

There are factual problems with this analysis: Corbyn’s massive mobilization of the Labour grassroots, who adore him, and his widely-praised manifesto and organizing campaigns, are clearly in part responsible for the party’s revived fortunes. But it’s also important to think about the premise of Blair’s argument: it’s not that adopting more conservative policies is right, it’s that it stands a greater chance of getting you into government. Yet if Labour is already doing well in the polls, and getting into government is within reach, why would you need to compromise? Surely, for a person of committed Left principles, the question is not “What should my political position be in order to maximize my vote share?” but “How radical can I afford to be without dangerously jeopardizing my chances of governing?” You’re not trying to get everyone to vote for you, you’re trying to get enough people to vote for you.

It’s true: by adopting positions that are further from the mainstream, you may make it harder for yourself politically. But that’s why you have to fight to persuade people. If you believe in something different than what the majority of people believe, you could just lie and pretend you share their beliefs. Or you could work to bring them around to your side. It’s one of these options or the other. If you succeed at the second one, though, you will have gotten far closer to your actual political goals.

I happen to think that principle is pragmatic. Sometimes there is a serious tension between the two, and you’ll have to do things that make you uncomfortable. But on the whole, a person who takes a firm stance, while they may have to do more work than the person who alters their position to reflect the vagaries of public opinion, will get more done in the end. Bernie would have won, even though his political position is outside the mainstream, and Corbyn stands a good chance of winning. If these two men were far less radical, if their stances were mushy and shifted constantly, they would not have attracted nearly the support that they have succeeded in attracting. As my colleague Michael Kinnucan has pointed out, Republicans have achieved political success through a total unwillingness to compromise on anything. The conservatives who have been moderate and reasonable have been pushed out of office, with hard-liners dominating the party.

Of course, it’s not so simple as believing that obstinacy leads to political success. After all, Republicans may dominate Congress, but they aren’t actually particularly effective at legislating anything. And if Bernie Sanders had embraced “real” socialism rather than using “democratic socialism” as a synonym for “Nordic social democracy,” he might have a harder time putting his case to the public. There is no actual simple rule for how to balance idealism and realism. But the first step is to make sure you’re actually asking the question. You can’t just dismiss objections to your expedient acts by saying that “the ends justify the means.” We have to have a clear understanding of which ends would justify which means, and which would take us too far in the direction of “becoming the very thing we’re trying to destroy.”

One reason I don’t trust Tony Blair is that I don’t think he’s being honest in his pragmatism. I don’t think he’s a committed socialist who just believes that the best way to get there is by softening our rhetoric. I think he genuinely doesn’t share my vision for what the world ought to be like. Discussions about when to compromise are only possible among people who share the same view of the ultimate end goal. Sometimes, conflicts between “centrists” and “leftists” are conflicts between “people who believe in going slow and being careful” versus “people who believe in going fast and being ambitious.” In those cases, we agree on what we’re trying to do, and are just having a comradely dispute on how to do it. But the dispute between “centrists” and “liberals” can also be a conflict between “those who believe the present balance of wealth and power in society is not especially objectionable” and “those who believe that balance needs to be fundamentally readjusted.” In that case, what looks like a conflict over “compromise” is in fact a conflict over something far more fundamental.

Here’s an incredibly obvious truth: if you care about principle, but don’t care about power, you’ll never get anything done. And if you care about power, but don’t care about principle, you might get something done, but it will be utterly worthless and will possibly kill a lot of people. Your values should include political efficacy, as well as a theory for what you will accept and what you won’t. But the most important thing is: beware anyone who uses the words “compromise” and “realism” to justify unscrupulousness, as well as anyone who uses “principle” to justify inaction and self-sabotage.