The Democratic Party Just Admitted It Doesn’t Stand For Anything

The slogan “Have You Seen The Other Guys?” shows the party’s total lack of positive vision…

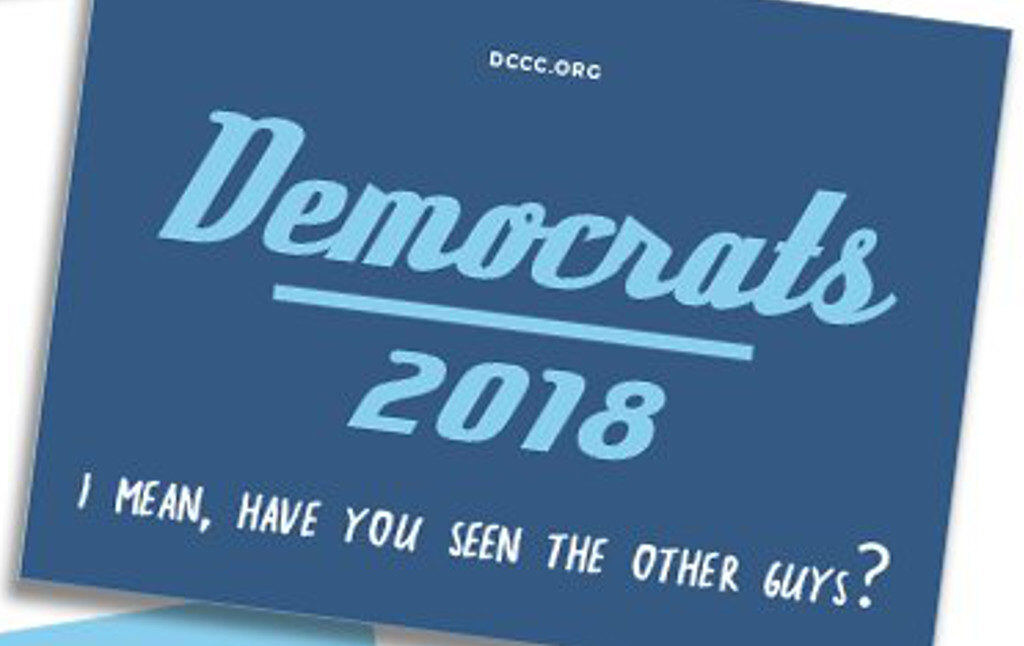

The Democrats are trying out new campaign slogans, and all of them should leave progressives deeply worried. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) recently sent out a series of proposed bumper stickers, asking party members to vote on which they liked best. The four possibilities included: “Resist, Persist,” “She Persisted, We Resisted,” “Make Congress Blue Again,” and, most tellingly of all, “Democrats 2018: I Mean, Have You Seen the Other Guys?” Many of those on the party’s left have long been concerned that contemporary Democrats don’t seem to actually stand for anything beyond “not being Republicans.” The bumper stickers seem to confirm exactly that.

The party’s struggle to offer voters reasons to support Democrats has been going on for some time. Bernie Sanders has said explicitly that he doesn’t know what the party’s political principles actually are these days, and even Vox’s Matthew Yglesias has suggested that the party “could use a substantive agenda.” But party leaders seem to have adopted the position that having a “substantive agenda” would be unduly divisive. That could be seen very clearly in the recent special congressional election in Georgia: Democratic candidate Jon Ossoff, funded by tens of millions of dollars from the national party, carefully refrained from advocating any actual policies. His advertising focused on pointing out the (obvious) fact that he was not Donald Trump, and the closest he came to proposing any legislation was in his plan for “consolidating federal data centers,” a policy so arcane that it would put even the wonkiest Capitol Hill politicos to sleep. The presidential campaign of Hillary Clinton was similar: Clinton’s strategy was entirely focused on issues of character rather than plans for how to make voters’ lives better, to the point where almost nobody can name a single thing Clinton was promising to do as president. (If you don’t believe me, ask your Clinton-supporting friends what her policy proposals were.)

The bumper stickers are the absurd logical endpoint of this approach. Note that they do not imply anything about what the Democrats’ actual values are. It’s not “Democrats: Fighting For a Humane and Decent World,” or “Democrats: Because Your Health and Happiness Matter.” It’s just “Democrats: We’re Not Them,” a statement that is totally empty of meaning. (It is, after all, true by definition that Democrats are not Republicans.) The differences between the parties are reduced to the fact that one of them is the Red Team and the other is the Blue Team.

This kind of focus, on why Democrats aren’t Republicans rather than what Democrats actually are, is a strategic disaster. Hillary Clinton lost, Jon Ossoff lost, and since 2010 Democrats have been losing catastrophically at every level of government. Formerly safe blue states now have Republican governors, and in red states Democratic opposition has collapsed completely. Worse, there seems to be almost no recognition in the party leadership that there is even a problem: Nancy Pelosi has flatly rejected the idea that the party needs to change, and if the new bumper stickers are any measure of what the DCCC is planning for 2018, the party’s messaging is only going to get worse rather than better.

At first, it’s difficult to see why Democrats are incapable of offering voters anything substantive. After all, this doesn’t seem to be an inherent “left versus liberal” or “Sanders versus Clinton” problem; it’s less that the party needs to “move toward the left” than that it needs to “move toward something,” and you can certainly have an agenda without it being a particularly progressive one.

But the “progressive versus centrist” divide within the party is actually key to understanding the problem. The reason the Democratic Party doesn’t stand for anything is that party leaders want to court both moderate Republicans disgusted by Trump and millennial socialists energized by Bernie Sanders. Because these two groups agree on almost nothing, the only possible way to unite them is through focusing on their shared antipathy for the president. It’s a political approach pioneered by Bill Clinton in the early 1990s, who built a coalition by simultaneously appealing to conservative-leaning Reagan Democrats and liberal Gen-Xers. The way it works is this: you make sure not to propose anything that might upset the existing economic order (such as single-payer healthcare or serious action on climate change), then you throw a few bones to the progressive wing by using the language of civil rights and resistance (Hillary Clinton, for example, tweeted using the language of “intersectional” feminism, and Ossoff was proudly pro-choice.)

It actually sounds like sensible politics, on the surface. And it worked for Bill Clinton. Remind progressives that their only other option is the Republicans, and then reassure moderate conservatives that you won’t go after big business. You might lose a few hardcore lefties, but you’ll more than make up for it in the number of Reaganites you peel away from the other side. (Or, as Chuck Schumer put it, “For every blue-collar Democrat we lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs in Philadelphia.”)

But this philosophy is a dead end. For one thing, it doesn’t work. Unless you have Bill Clinton’s special charismatic magic, what actually happens is that progressive voters just stay home, disgusted at the failure of both parties to actually try to improve the country. And the mythical “moderate Republicans” never seem to show up. (This is because there are no actual moderate Republicans.) And it’s not just electorally unwise: it also gives up on the idea of actually changing anything, with the only goal of politics being to attain political office. It precludes the possibility of ever taking serious action on healthcare, the environment, nuclear arms, housing, or any of the million other issues that require urgent and serious action.

The DCCC’s new bumper stickers show a party doubling down on a losing strategy. The party no longer has anything to offer voters. Until that changes, voters will continue to respond in kind, by being as enthusiastic about helping the party as the party is about helping them: not at all.