Trump’s NSPM-7 is a Threat to Every American

Investigative journalist Ken Klippenstein exposes the new threat to free speech: branding any and all dissent as “terrorism.”

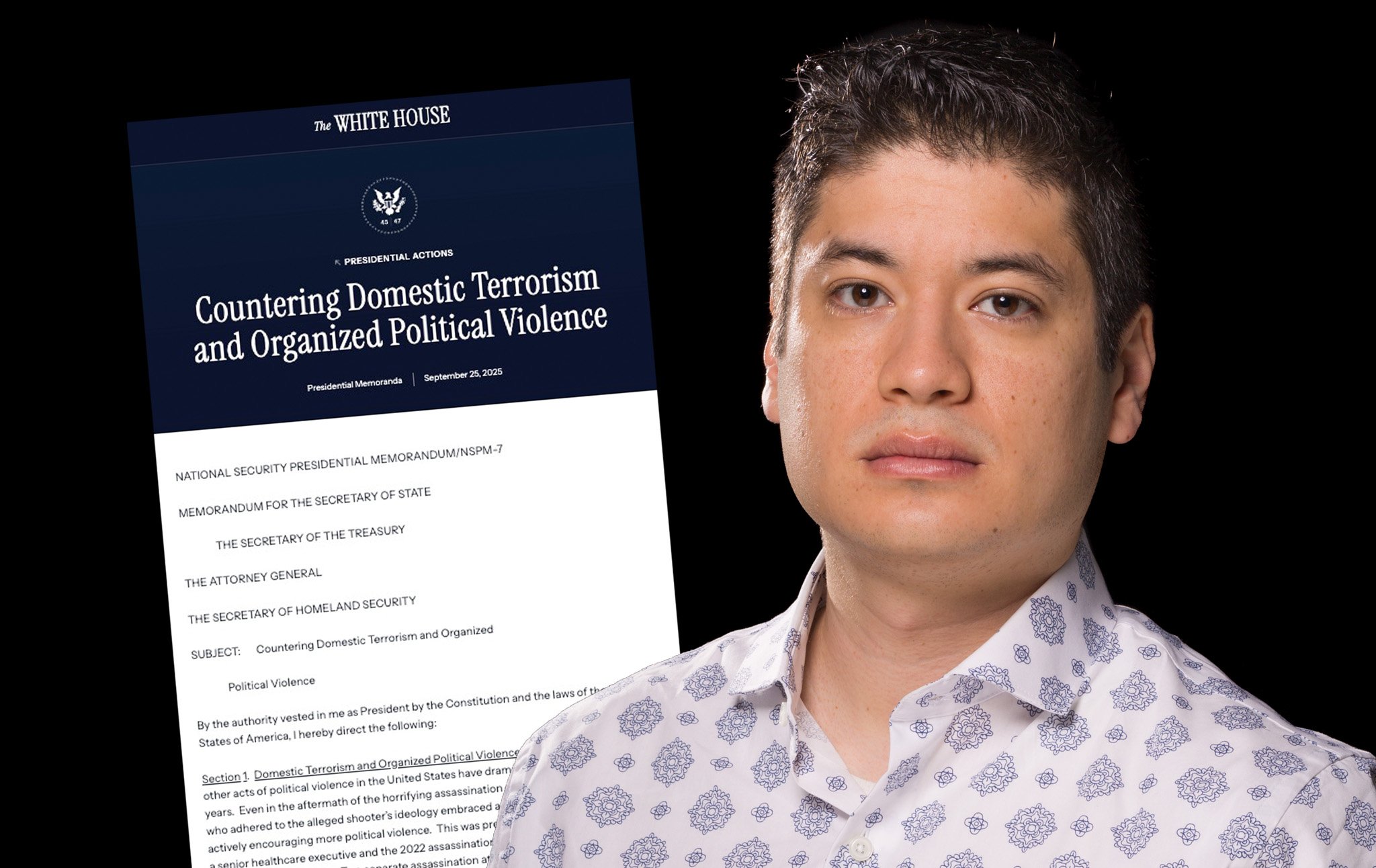

Ken Klippenstein is an independent investigative journalist and proprietor of Klip News. He’s published scoops on Luigi Mangione, leaks from the Trump administration, and lots of other important information you won’t find at the big news networks. He joined Current Affairs editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson to discuss how mainstream media has been captured by government sources, why national security reporting is uniquely broken, and his recent reporting on Trump’s new presidential directive, NSPM-7, a sweeping order that directs federal agencies to treat political dissent as a form of domestic terrorism.

Nathan J. Robinson

Before we get to your recent reporting on the terrifying new Trump presidential directive, I want to ask you a couple of things about being independent and the kind of work you do. Because if people go to Klip News and click about, they will see some explanations for your kind of philosophy of journalism. And so I just want to read something from your website:

“From the Pentagon to the FBI, these state agencies are currently running circles around a press captured by government sources, industry, and obsolete journalism conventions.”

Now you kind of famously left the Intercept to go out on your own, and I wondered if you could first elaborate on this failing in mainstream journalism that you’re talking about in that passage there. What is it, exactly?

Ken Klippenstein

Yes, national security, particularly since there’s so much secrecy endemic to it—not just with classification, but just a culture of secrecy—it can be especially hard to find out what it is that’s going on. That is compounded by the fact that at major media institutions like the New York Times, the Washington Post, CNN, and so on and so forth, to get footing with these agencies and be able to get exclusives regularly and get public affairs to pick up the phone, you’ve got to cover them a certain way. That kind of source capture is what has been behind story after story that I’ve fortunately been able to do independently, and I think I’d have a lot of problems doing that at those institutions.

One example would be the so-called manifesto left behind by the alleged gunman, Luigi Mangione. Virtually every major paper had this. I don’t want to paint with a broad brush here. I know a lot of good reporters at these institutions who themselves, had they been given the choice, would have published that. But in the case of Mangione, law enforcement had circulated this with the agreement that you don’t publish this if we give it to you. They’re not going to come in on black helicopters and arrest you if you don’t listen to them, but they’ll stop answering your phone calls. They won’t be a source anymore. And so that is the kind of soft blackmail that exists in national security reporting. And again, it’s endemic to the field.

Robinson

Because there have been a number of examples now where you’ve broken stories that you haven’t been the only one to know, but other outlets have chosen to sit on it and not report something that they had.

Klippenstein

Yes, I appreciate this mystique, that people think I’m some kind of magician, that I can just get these things every time. But the truth is, sometimes I get stuff that no one else can, but other times, these are things that these news outlets have. What’s another example? The JD Vance research dossier—the vetting dossier that the Trump administration had put together when they were trying to pick, at the time, who their vice president would be—was something that all these institutions had. Nobody wanted to publish because they didn’t want to run afoul of, again, these institutions. Some of it is human. You don’t want to make life more difficult for your co-workers. You don’t want to make life more difficult for the masthead. If you do something that runs afoul of their sources, they’re going to be upset with you. So it’s not all insidious. Some of it is just not wanting to rock the boat and make other coworkers lives difficult. But at some point, I think you have to look at it and say, What is the public interest here? And see that as the transcendent concern, rather than collegiality or whatever it is.

Nathan Robinson

Now, if I were to talk to people from outlets that didn’t run things that you had run, I think what they would probably tell me is that no, this has nothing to do with preserving our access and everything to do with our looking out for the public interest. They would say that there is a risk in publishing the manifestos of shooters, that you’re going to inspire copycats, and they’re behaving responsibly. Or in the case of the dossier, they would say false information is pushed by entities with an agenda that we don’t want to further. We don’t publish raw material like this that could have negative consequences. And they might even, if they were particularly ill-disposed towards you, say that Ken Klippenstein is irresponsible because he doesn’t make these calculations. He’s just willing to put stuff out and let the public be the judge, but that is irresponsible. Now, how would you respond to someone who said that?

Klippenstein

Well, to the last point, I do make calculations on these things. There are certain things, about saying something about someone’s personal life, that I don’t think are newsworthy that I have and haven’t published. But to the broader point, that’s certainly the kind of PR statement that these institutions put forth, that they’re overflowing with love for the public. I think it’s very paternalistic to say, we can circulate this. I know reporters were sharing a lot of these same things we’ve been talking about among themselves. Somehow they’re immune to these negative consequences of consuming the information, but it’s the general public that, when they look at it, are going to just snap to attention like some Manchurian Candidate and have to act out whatever it is the manifesto says. So I think there’s a little bit of a double standard going on there, because they’re happy to read them themselves, and they do, and I would as well. But I think it’s a little bit inconsistent.

But to the broader point, I think that there are probably plenty of people who say that and do believe it sincerely, and it’s not a cynical PR ploy. I would draw a distinction between people at a newsroom. I know some of the best-known and best national security reporters at these outlets, and they tell a very different story. They’re in the room that’s actually making the decision, and they understand the access that’s at the heart of this, and so they hear a different story than what the rest of the media institution hears. And I think it’s probably worse on national security. I think probably a lot of people would agree with me that coverage of war and law enforcement is like a tier below even what media coverage is generally. How often do you hear a story that’s like, wow, the Defense Department really didn’t want that out, or the CIA really wouldn’t like this out? Not very often. And that’s because it’s just a more difficult space to operate in, and it’s more captured, I think.

Robinson

And the excuse always is, “It’s national security; you’re endangering lives by publishing this information, and everything that is done within these departments has to be kept secret for the [greater good].” After the Snowden leaks, that was what Glenn Greenwald was accused of: endangering national security. And so, obviously there’s a go-to justification.

Klippenstein

Which is a creepy tendency in itself. It’s like everyone has been deputized into the national security state, where suddenly some media editor is a counterintelligence officer. You see this every time a story comes out. Wait, that’s the government’s job. Our job is to get information of public interest out to the public, and even if that’s true, I don’t think that’s a healthy place for the media to be, thinking that we now also share in this responsibility to guard secrets. If a failure happened and someone like me found out about something, that’s the system’s fault. It’s not journalism’s fault, and I don’t think it should be our purview to worry about such things.

Robinson

I take what you’re trying partially to show with the work that you do is that you don’t actually need to agree to these terms. You don’t need to take this bargain to break stories. Because you famously do not take these corrupt bargains—“We’ll give you the documents if you refuse to share them”—one might assume that no one would ever share documents with you, Ken. That you would be the last person, and that you’ll never get a story because your access would be closed off. So how do you do this when you forgo the easy access channel?

Klippenstein

Yes, that’s a very astute point. I haven’t been a shrinking violet in terms of getting these leaks. And so it’s a big misconception that I think is inculcated in people’s minds, particularly in Washington, because the culture is just so self-dealing. I lived there for several years. I moved back to Madison, Wisconsin, recently. And what I saw there was everyone trading in that kind of business and thinking, and I think there was just this sense that this is how it’s done, and people don’t really question it. I don’t know how much it’s even thought of as something that’s untoward, and young reporters are brought up in this way. I remember hearing editors talk about establishing friendships with your sources, and as friends, they’ll help you. That comes with a whole host of problems, which is that you’re no longer putting the public interest first. You’re putting your personal friendship first, which, again, is human, and I understand, but it shouldn’t be something that you want to cultivate.

But in any case, that’s what Washington is rife with. So I think that’s part of it. But, yes, you don’t have to do that at all. I would say that I don’t have access to the same sources that they do. Public affairs is going to slam the phone down if I call them or if I go through the front door, but there’s also the back door, and there are all kinds of people in my experience, including in this national security apparatus that I’m so critical of, that are not just automata. They do have their own beliefs, and they do care about the Constitution, and they do care about the rule of law, and they’re motivated by things other than just career advancement, and for that reason, they will share things with me that they find troubling. And there are plenty of people like that, and I just don’t think you’re trained to look for them.

Robinson

Because I wanted to argue, not to give away the Klippenstein investigative trade secrets here, but people might wonder. You’ve moved back to Madison, Wisconsin. They might think, well, it’s incredibly difficult to do reporting on the national security state from Madison, Wisconsin—you’ve got to be in there, you’ve got to be taking people out, you have to be going places. And obviously, as you say, if you just call them up, you’re not going to get them to disclose anything. But a lot of what you do is disclosing government documents that people don’t want disclosed. How do you go about obtaining these things?

Klippenstein

Well, you have to be a very careful reader. I’ve been amazed how many times it is evident to me that major media don’t read past the executive summary. And if you can familiarize yourself with the material, then when you go to someone in the national security system, they have a certain internal culture. There’s one specific to the FBI, specific to the Pentagon, and even specific to individual service branches. But generally speaking, if you’ve done the reading and you’re familiar with the material, people kind of loosen up a bit and feel like someone’s already let them in. I’ll give you an example. I mentioned something while interviewing a young service member, and I knew this would signal to him that I had some familiarity with it. I referred to the U.S.’s secret base in Israel, just code-named Site 512. I said, “Oh, yeah, 512 blah, blah, blah,” and I just kind of dropped it. He goes, “You know about 512?” And I said, “Yes, I’ve been talking to you guys for years, like anybody who’s been paying attention to this stuff knows.” He kind of goes, “Oh, okay, well, since you’ve already been let in, here’s what I know.”

Robinson

“I want to tell you the rest of it, then.”

Klippenstein

So it requires a lot of, I think, diligence—or at least my approach has just been diligently reading things and understanding how it works so people don’t feel like they’re letting you in on something you don’t already basically know.

Robinson

It’s funny. Once you know about 512, they’ll tell you about 513.

Klippenstein

Exactly, yes.

Robinson

And so for any of our listeners and readers who may be unfamiliar with your work, before we get to the latest terrifying presidential directive, you mentioned the manifestos that people had. But what are some other examples, since you’ve gone independent, of documents you were able to find and stories that you’ve been able to break?

Klippenstein

So there was a manifesto of the alleged shooter of two diplomats at the Israeli embassy in Washington, which I thought was very insightful and that the media declined to publish. What it showed was that he was motivated by animus towards Israel, the State of Israel. This was a crime, if the Justice Department’s account is borne out, of geopolitics, not of antisemitism explicitly. And I really tried to find that. I went through a group chat that he had going for over a decade, I read through the whole manifesto carefully and everything I could find that he’d posted in the past, and I couldn’t find any overt evidence of antisemitism. And this is important because, as a country, when something like this happens, it’s understandable that you want to know what happened so that it doesn’t happen again. And if we have a wrongheaded idea of what it was that took place, how are you going to be able to address the problem of political violence? So the media just ran with this story of, “Oh, it must have been...” And as my investigation found, he was looking for people that worked for the embassy, officials of the Israeli government. So that’s different in character than kind of the general picture of it.

More recently, I talked to friends of the alleged killer of Charlie Kirk, Tyler Robinson, and they shared with me some of the Discord messages, which the New York Times didn’t publish. They did quote from it to their credit, and so did the Washington Post. But not only do they not publish the messages themselves, which have interesting details that even I don’t understand, not being someone who uses Discord—gamers notice things in these posts that I hadn’t noticed and add some color to the story. But in any case, I try to post the things whenever I can. My major constraint is worrying about sources, not wanting sources to get in trouble—people that have decided to share something with me. But often you can do that in a safe way that doesn’t get them in trouble. And when I went through more of the messages, it revealed that this guy was not this left-wing radical terrorist or whatever that the Trump administration very quickly settled on, and that the media more or less ceded. I think Charlie Kirk was such a politically polarizing figure that they kind of eyeballed it and were like, “Well, I guess that sort of makes sense.” The reality was much more subtle than that. You wouldn’t know that without these primary source records, not just for me to go through, but for people steeped in the culture of Discord and the gaming world and all this.

So that would be two examples. It’s kind of gratifying in a way, because when I was at these institutions like the Intercept, I remember thinking to myself, “I wish I could publish this.” I give you one explicit example. I had early access to the Jack Teixeira documents, the U.S. airman who leaked all these top secret records on Discord, again, of all places, and I wanted to publish it. And then the editor in chief was like, “I don’t know about this—no one else is publishing it.” So when you leave an institution like that—I just saw today, somebody was criticizing Substackers who leave and say they want to stick it to media. I really have repeatedly published things that I demonstrably could not have published at that institution. This is not a branding exercise. It is literally the truth that at those institutions, you’re just encumbered by all of these constraints and conventions.

Robinson

Yes, the Intercept is kind of a sad story, because it was obviously founded specifically to try and buck those conventions. It’s a real shame. That’s the place that you would expect, if any institution would be bold enough. But one of the things you published after you left was the Intercept org chart. The striking thing looking at that was just how bloated it was with creative, strategic directors and people on the business side.

Klippenstein

Everything but journalism. Maybe it’s changed, but at the time that I was there, it was like one story a day, and it was a staff of dozens and dozens of people and millions of dollars and resources. It’s really a shame.

Robinson

Because they had really great journalists too. You were one of a team of real all-stars, and most of them have been driven out or laid off.

Klippenstein

Yes, there was a big wave of people after I left. Ryan Grim left as well, the bureau chief that I had worked under. Jeremy Scahill did too. But that’s kind of the media landscape now.

Robinson

So what you’re saying there is the importance of these things, even these manifestos—we discussed this idea that if you talk about them, it’ll be dangerous. But then you had the other one about the guy recently in New York—there are so many shooters, it’s difficult to keep track of—who was blaming CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) for his [actions]. And if you don’t understand what their grievances are, you really don’t understand what’s causing the horrors that you’re seeing. It’s like the bin Laden letter. It’s not sympathy with bin Laden, but you’ve got to read the bin Laden letter if you want to understand 9/11.

Klippenstein

When the NFL shooting happened, I was just curious: why would someone target the NFL? It quickly came out that he had played football. Then the national question is, I wonder if there was some sort of grievance there. And even raising the question is regarded as somehow downplaying the crime, which is just absurd to me. It’s unfortunate that freedom of expression and speech has become this sort of partisan-coded idea, because I don’t see it that way at all. To me, having things out there so that there’s not an underground, that we can try to adjudicate problems in the society, is core to any civilization. And I don’t understand why it’s this right or left thing. That should just be a common-sense endeavor.

Robinson

And you’ve also reported recently on U.S. military preparation and action against Mexican drug cartels and against Venezuela. These are things that are incredibly dangerous, and not only threaten to violate international law—in fact, are explicit violations of international law, which bans the threat of force—but are a threat of force against these countries. And there’s very little about these in the mainstream press. Oftentimes these are things that are, I take it, not that difficult to find out about, but for some reason, they’re just kind of overlooked by other outlets.

Klippenstein

Yes, in that case, I found that the Pentagon’s intelligence agency, called the Defense Intelligence Agency, is already drafting up what are called “target packages” to strike certain cartel leadership and infrastructure in the event that the President goes ahead and does that. Something I think that people don’t often understand about the military is how much logistics is involved. It’s not like Hollywood, where the President has an idea, says it, and the generals go in; you’ve got to set up. Depending on the distance from an air base, you’ve got to have midair refueling, and you have to have the right kinds of munitions that you want. Is it a targeted strike? Are you trying to kill an individual and minimize civilian casualties around it? Are you trying to collapse an entire building? All of these things require preparation, exercises, and training. So to do something like what the Trump administration seems to be implying, some sort of pressuring of the Venezuelan government, who they believe, or they say they believe, is manipulating the cartels—in fact, we know the intelligence community doesn’t think that there’s solid evidence for that, but in any case, that’s what they say—if they go ahead and do something like that, that’s a huge structure that you have to build up, just like when you’re going into Iraq and you’ve got a station out of Saudi Arabia and Qatar and all these countries. This stuff is not trivial. So there’s always a contrail, so to speak, that’s left behind when they’re trying to do something like this.

I think one of the most unhealthy parts of conspiracism—conspiracy theory thinking—is how disempowering it is. [The idea that] there’s nothing we can do. There are all kinds of signs of what they’re up to. It’s just that, as you say, the media doesn’t talk about it. Part of that, I think, is how narcissistic the media is. I mentioned the national security reporting space in Washington, and that means they talk to their Washington sources. I have great sources in places other than Washington. There are military bases all over the country. There’s a major military base within an hour of where I live. There are generals that work there. There are intelligence people that work there. There’s a whole world of sources that are completely untapped. It reminds me of when kids are playing soccer, and they all just mob around the soccer ball, and there’s no strategy to hold back and defend the goalie—you know what I mean? So that’s kind of what I see the press as. I’m not saying there shouldn’t be coverage in Washington. Of course there should. But it’s so duplicative, and there’s so much of it, with so many of the same stories based on that set and what it is that they’re looking at. I suppose Washington probably knows about the planning around these strikes, but since it’s not really an action item in terms of the rhetoric that they’re pushing, they’re so domestically and internally focused now that I just don’t think it comes to mind as something that you should investigate and go make some phone calls about.

Robinson

Now I want to ask you about repercussions here. We’ve been talking about the kind of journalism you do, and let’s say that it is not calculated to piss off national security officials and law enforcement officers, but it would seem to naturally have that effect. These are people who have tools that they can use to try and intimidate and get back at critics. We can expect that Ken Klippenstein is the kind of guy who gets a knock on the door from law enforcement agents from time to time. Is the strategy to ignore you? Have there been attempts to intimidate you? How does that go?

Klippenstein

Well, I’ve gotten two visits from the FBI in the past year, and the first one was in response to the Vance dossier that we were talking about before. It was kind of funny and, in some ways, instructive. I always complain that people see the national security state as Jason Bourne. It’s really more Burn After Reading, and this experience illustrated that perfectly. So I got a knock on the door, and I went to open it. No phone call beforehand, of course. And it’s this very young, pencil-necked kid who was polite. He was so young he looked like he might have tripped on his umbilical cord on the way over. It was like you wanted to pinch his cheeks. He introduces himself, and he’s actually kind of apologetic. He’s like, “I don’t know about this—I don’t know that the Bureau should be talking to journalists like this—but in any case, I got sent here by Washington, and I’ve got to read you this statement.” So he has a piece of paper that he unfolds, and because the Vance dossier was assessed to have been hacked by the Iranian government, he reads me a statement to that effect, saying, “You’ve been the target of a foreign malign influence campaign,” or recipient, something like that.

He finished his reading of it, and I said, “Yes, I know. I wrote that in the first sentence of the story.” Because my view on this is that this binary of “do you publish or do you not” is crazy, because there’s a whole chasm between the two—how you responsibly inform the public about the provenance of a document so they can factor that into their own conclusion about what the newsworthiness is. And so in the first sentence, I said, “This is assessed to have been hacked by the Iranians. The Iranian government doesn’t like the Trump administration because of X, Y, and Z policies. Put that into account as you read this, realizing that they want this out there for that reason.”

And so I said that to him, and he goes, “Oh, really? I haven’t read the article.” And I said, “You got sent here, and you haven’t read the article?” He’s like, “Yes, honestly, my boss said I had to come down here.”

He was working from a satellite office in a suburb, maybe 15 minutes from here. The FBI has a huge presence, not just a field office in every state, but also what are called resident offices. They’re like little satellite offices everywhere. Anyway, I kind of laughed about that, and I joked, “I was expecting you guys to come a little faster, because I did think that there was a risk of something like this happening.” He goes, “When did you publish the document?” Which is funny in itself. He didn’t know the date. I said, “About two weeks ago.” And he says, “Well, two weeks is pretty fast for the federal government.” So that gives you a sense of just the Catch-22 vibe to this whole thing. So I’m more worried about my sources than I am about myself. My sources take far greater risks than I do.

Robinson

I want to ask you about the reporting you’ve been doing most recently, because this is a very clear example of one of those stories where, as much as we may give credit to your investigative abilities, the core of the story is literally a thing that the President signed out in the open and not very difficult to find out about. But you said this is a case where the mainstream media was just distracted by this thing. It doesn’t really notice the implications of the directive.

Klippenstein

Yes, NSPM-7. It stands for National Security Presidential Memorandum 7. There have only been seven of them this term. This is completely distinct from executive orders, of which there have been over 200 at this point. But the media conflated the two, and you can find several articles that still haven’t been corrected where they describe it as an executive order. And my guess is that that’s why this got overlooked. They were like, “It’s another one of these 200 things.” So in the case of executive orders, some of them can be significant, but in many cases, it’s narrow day-to-day operations of government stuff, whereas a presidential memorandum is a sweeping strategy statement that tasks the entire federal government, saying, “These are our priorities for the rest of the administration; focus on that and carry it out.” That’s what the chief executive says.

And so not having the national security chops to realize this, because it’s a subtle difference, I can see why you would mix them up. They’re posted to the White House [website]. He’s always doing these provocative executive orders. So I kind of get why it wasn’t easy. What I was surprised by was that the national security specialists didn’t say something about this, because just to give you a historical example, during the Carter administration, they had a National Security Presidential Memorandum. Often they’re classified. In the case of Trump, we’re talking about NSPM-7. The sixth was classified. We don’t know what it was. So in the case of Carter, when one was, I think, declassified, it showed a huge change to nuclear policy regarding the then USSR. There were massive protests in opposition to this. It became a huge political firestorm. And I think that’s the appropriate response because these are major decisions, and if it’s a decision that departs from past or popular practice, it makes sense that people would have that reaction. So in this case, I think it should have that reaction.

And just to run down what NSPM-7 is, it’s tasking all of federal law enforcement to prioritize domestic terrorism, and the way that you go after terrorism is different from normal crime fighting. For ordinary crime fighting, a crime has already been committed, and then you work backwards to try to find evidence of who committed the crime, and you charge them. In the case of terrorism, you’re basically getting into pre-crime because you’re trying to preempt the attack. So from the perspective of proponents of counterterrorism theory—I’m trying to be generous to them here—one can imagine certain forms of attacks necessitating preemption. Say there’s a dirty bomb or a nuclear weapon or some huge attack like 9/11; I can see more why you would want to consider preemption. But in the case of NSPM-7, it lists Kirk’s assassination and other forms of political violence that have taken place, much smaller in scale than anything, I think, that would necessitate a counterterrorism response. But in any case, that’s what it orders.

Since a crime has not been committed in the case of terror, you’re trying to prevent a terrorist attack. How do you go after it? Well, you need something called indicators—again, pre-crime. Indications of the likelihood of a future crime. It lists those indicators very explicitly. I’ll give you just several examples, or maybe a dozen or so: anti-Christianity, anti-Americanism, and I think one was anti-traditional family values. So sweeping categories that I imagine would cover millions and millions of people. And I was honestly shocked when I saw it, because I knew this wasn’t an executive order. I knew this was telling the Justice Department and the FBI field offices—again, in all 50 states—to prioritize this. And there’s this lazy response by the media in two ways. One is to say there’s no law for domestic terrorism. So again, it’s a little bit subtle. They’re correct. That’s narrowly true. There’s no domestic terrorism statute. That doesn’t mean the FBI can’t investigate domestic terrorism. It doesn’t mean the FBI doesn’t have a domestic terrorism list, which they do. That means they can open up cases with this very light predicate that I just described, these so-called indicators.

So that is what the terrorism charge allows them to do. Maybe you won’t face charges for it in court, but the FBI can look at you and then find other charges that they could actually bring against you. So it’s a subtle difference that the media has completely missed. In the case of all these indicators, I think there’s this impression that it’s so broad. How are they going to do this? They all are already acting on this memorandum. Within two days, Pam Bondi put out a document showing that they’re creating an anti-ICE Crimes Task Force, citing throughout it this memorandum. For nonprofit groups, the memorandum directs the Treasury Department to start monitoring cash flow because they are convinced that there’s some kind of orchestrated campaign of financing so-called left-wing radical terrorism. So law firms are already advising their clients in the nonprofit space to adopt different language so that they don’t run afoul of the law. I’ve talked to people at nonprofits that are saying they’re behaving differently. So it’s already having a chilling effect on speech. The question is, to what extent will they go after these indicators and investigate terrorism through this network of thousands of what are called Joint Terrorism Task Forces established after 9/11 and existing in every single state? To what extent are they going to send those after people? And that’s what we don’t yet know. But everything else that I’ve described has already happened.

Robinson

It is no conspiracy or exaggeration to point out that the history of the FBI shows that in the ’60s and ’70s and after 9/11, there were active efforts not just to investigate but to plant moles in left-wing and activist organizations to try and foment discord or provoke people into committing something that could be a crime. One of the things that was so scandalous after 9/11 was the FBI finding hapless, mentally ill Muslim men and trying to convince them to plan a terror attack so they could show that they’d stop the potential terror attack. That’s happened. And if they take this directive seriously, it directs them to do more of this. As you say, the list here is really remarkable. In groups like the DSA, people might think, “Obviously we’re completely nonviolent, so we don’t have anything to fear.” But it says “groups that foment political violence before they result in violent political acts.” And then, as you say, the list is anti-Americanism, anti-capitalism, anti-Christianity, support for the overthrow of the U.S. government, extremism on migration (anyone who supports more liberal immigration policies), extremism on race (anyone who says racism exists), extremism on gender (anyone who’s pro-transgender), and hostility towards, as you said, traditional American views of family, religion, or morality. It’s really so broad that it captures basically everyone to the left of MAGA. And depending on how seriously this order is taken, it includes not just investigations but efforts to “disrupt” the political activities of basically anyone who isn’t MAGA.

Klippenstein

Yes, counterterrorism is a very ugly business. Again, when you are trying to preempt a crime before it has happened, how do you find out about it? You definitionally have to look at speech, because that’s the only way that you can get some indication of what’s going on. How do you monitor speech? That could be social media monitoring, or that could be a whole army of informants, which the FBI already has. You can read about them in the inspector general reports that the Justice Department puts out on the FBI. It goes right back to when you were mentioning COINTELPRO earlier. Well, that’s how you find out about things before they’ve happened. You have what are called “trip wire individuals” in different organizations or offices, people that can flag something for you that’s of interest.

And what I want to stress most of all is just because you don’t engage in violence doesn’t mean that you don’t meet any of those other indicators. Then at that point they can open up an investigation, and they’re looking at your taxes. Did you file your taxes correctly? There’s a whole continuum that media just misses. They’re saying, “Is Trump going to do the maximalist approach to this? Is the Justice Department and law enforcement going to do the maximalist?” But that’s not the question. But that’s not the question. The question is, where in this continuum? And we’ve already seen nonprofit organizations being advised and taking advice to talk differently. We’ve already seen the chilling speech effect. And there’s this whole distance between rounding everyone up and just causing headaches with taxes, for instance. That could be another step along the continuum. There are all kinds of ways that this could be implemented, short of some kind of Alex Jones fever dream. And that’s what the media misses when they give this very lazy and reflexive response that Trump says a lot of things. How do we take it seriously?

Robinson

Yes. And you also point out in your reporting the fecklessness and weakness of the Democratic opposition. We talk a lot about this at Current Affairs. It’s not just a media failure of reporting, but you point out that almost no members of Congress have even commented on this new directive.

Klippenstein

Yes, I can’t stress enough how interested ordinary people are in this story. A couple of days after my story, moms are emailing me about how they’d like to learn more. How can I get involved in this? So it’s a lie that it’s too subtle. I can’t tell you how many times in media people are told this by editors. Oh, it’s too in the weeds, this kind of thing. I have not seen that to be the case at all in terms of the numbers of readers, and just anecdotally, people responding to it. So part of that was a couple of days after, a reporter at Courthouse News was clearly interested in the story and realized what we saw in it, which is this is really crazy. So he just physically runs up to some of these members on the Hill who have committee assignments related to national security and just asks them, “Hey, what do you think of this?” So he asked, in one case, Dick Durbin, who is the, I think, number two Democratic senator in the Senate—a very powerful individual, ranking member overseeing the Judiciary Committee, whose responsibility is overseeing the FBI. It’s like their whole thing. And he asked him, “What do you think of NSPM-7?” He goes, “I don’t know what it is. This sounds bad.” And then he goes up to Elissa Slotkin—I always joke and call her the senator from Langley, because she’s always talking about her CIA service, which I don’t think is disqualifying, necessarily, but she’s constantly like, “I’m a national security expert.”

Robinson

Which is nothing to be proud of.

Klippenstein

She has a video series called the Intel Briefings. She brands herself around being this expert. It’s her whole thing. And they asked her. Same answer: I don’t know what it is; it sounds bad. And then this weird, wishy-washy response—you should read it. It’s really crazy. She says, “But violence on both sides is a problem.” It’s like, what? That is your reaction to this?

Robinson

Well, it is remarkable. And you talked to law firms who said, “Yes, this has very serious legal implications.” There is always this danger, as you’ve mentioned, because Trump does a hundred things a day. It’s the Steve Bannon phrase “flood the zone”: we’re going to do so much shit that people can’t tell the nonsense things that don’t matter[...] from the things that are really serious. And as we’ve emphasized here, the text of the directive suggests it’s targeting inciting violence, but then it defines violence in a way that includes nonviolent actors. It says they have to stop violence before it happens, and all of these are things that basically hold any political position that isn’t in complete agreement with the administration. It’s anything on gender, anything contrary to family values—there are 10 points, and if you believe in even one of those points, then you are a potentially violent actor. It has essentially defined all political dissent against MAGA ideology as potentially fomenting violence and directed state agencies to investigate and disrupt it. That’s what we’re ultimately talking about, if we’re being clear.

Klippenstein

Yes, that counterterror approach is key to understanding why this is different and how, because that introduces an entirely different approach to going after things. You don’t have to have committed a crime for them to look at you, and the Trump administration, both Trump personally and Stephen Miller, his homeland security advisor, in particular, have made abundantly clear that they are just talking about the garden-variety left. Trump keeps talking about the Soros Foundation and how they’re going to look at their funding structure. This is well within the mainstream. That’s closer to the center than all sorts of activist groups. So this is not some fringe group you’re looking at, like CHAZ or Stop Cop City or something. This is well within the mainstream of the country.

What’s more, just to make the point that this is not just rhetoric, Kash Patel, a couple of weeks ago, right after Charlie Kirk’s assassination, testified to Congress that there has been a 300 percent increase in domestic terror investigations opened up by the FBI since his appointment. And so it’s already happening. They don’t immediately announce the investigations that they have opened. The ones that we’ve seen brought to trial are the result of, often, years and years of investigations. So for the vast majority of that, we don’t even know what it is. The only hint we have was what Patel said, which is that a large chunk of it is “nihilistic violent extremists.” In the past, the FBI has used these categories to hide political actors under so that when they have to provide data, they can say that it was an explosion in “nihilistic violent extremists.” Because they’re not going to want to say, “the Democrat category went up.” They’re smart enough bureaucratically to understand you shouldn’t do that. So the question is, what’s going on in this huge explosion of domestic terrorism cases and now with this new directive that supercharges the national security system?

One last thing I want to say here: these Joint Terrorism Task Forces that are responsible for carrying a lot of the stuff out on the ground, he doesn’t have to build that logistical infrastructure that I was describing before. The JTTF (Joint Terrorism Task Force), since 9/11, exists in every state. And what’s interesting about them is, unlike the National Guard, they are not restricted by posse comitatus. When you see the National Guard, as you said earlier, people often might not know what is just Trump talk. I think with a lot of the National Guard stuff, I’ve characterized that as theater, something that should certainly be opposed and that is corrosive to the democratic culture, no question. But the reason they’re wandering around picking up trash is because they literally don’t have the legal authority to go and do something, so they’re really restricted in that way. But what’s sort of ingenious about what this memorandum does is these Joint Terrorism Task Forces, just like the Guard, exist in every state; they can be tapped and tasked at any moment. But they don’t have posse comitatus because they’re law enforcement. So this is a really useful arrow in Trump’s quiver that we have yet to see how it’s going to be applied.

Robinson

Well I’m a little concerned because I realized that I qualify for, I think, about nine out of the 10 categories.

Klippenstein

High score.

Robinson

I don’t support the overthrow of the United States government, although I’m sure they would classify me as supporting things that are tantamount to that.

Well, one thing just to emphasize at the end here is that what constitutes the news is manufactured by editorial choices. And if the New York Times wanted to, they could blast the headline above the fold—a giant headline spanning the entire front page of the paper.

Klippenstein

And I guarantee you, if they did that, Congress would then act. So much of this is about information bubbles. It’s not so much nefariousness. In some sense, it’s even worse than that. If it was nefarious, at least they would know what’s going on. I think they’re genuinely clueless. Because these guys on Capitol Hill—I lived there for five years—they’re reading the New York Times, and they’re watching cable news. That’s it. They’re not watching anything else.

Robinson

You can imagine if the front page of the New York Times said, “Trump orders all state resources towards a massive crackdown on all beliefs other than his own,” people would wake up. But there’s an editorial choice made. And I think one of the reasons you’ve been something of a—I say this as a compliment—broken record on this directive is because you’re pleading with people to treat this with the seriousness that it objectively demands.

Klippenstein

Yes, in which only those papers have the privilege and power and authority to reach those officials in government. I don’t want to say all officials. Congressmembers Mark Pocan and Pramila Jayapal are circulating language on this, so certainly some members of Congress have responded to it. But I’m saying, by and large, the political establishment has not, and that’s what I’m trying to draw attention to. Like the Iraq War, once you’ve gone in, it’s too late then. I would love to have us preempt something just like the national security state is constantly trying to do with this counterterrorism stuff.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.