From Taylor Swift to Lil Wayne, beloved musical acts have been releasing albums way below their usual standard. As usual, it’s the big labels and streaming platforms to blame.

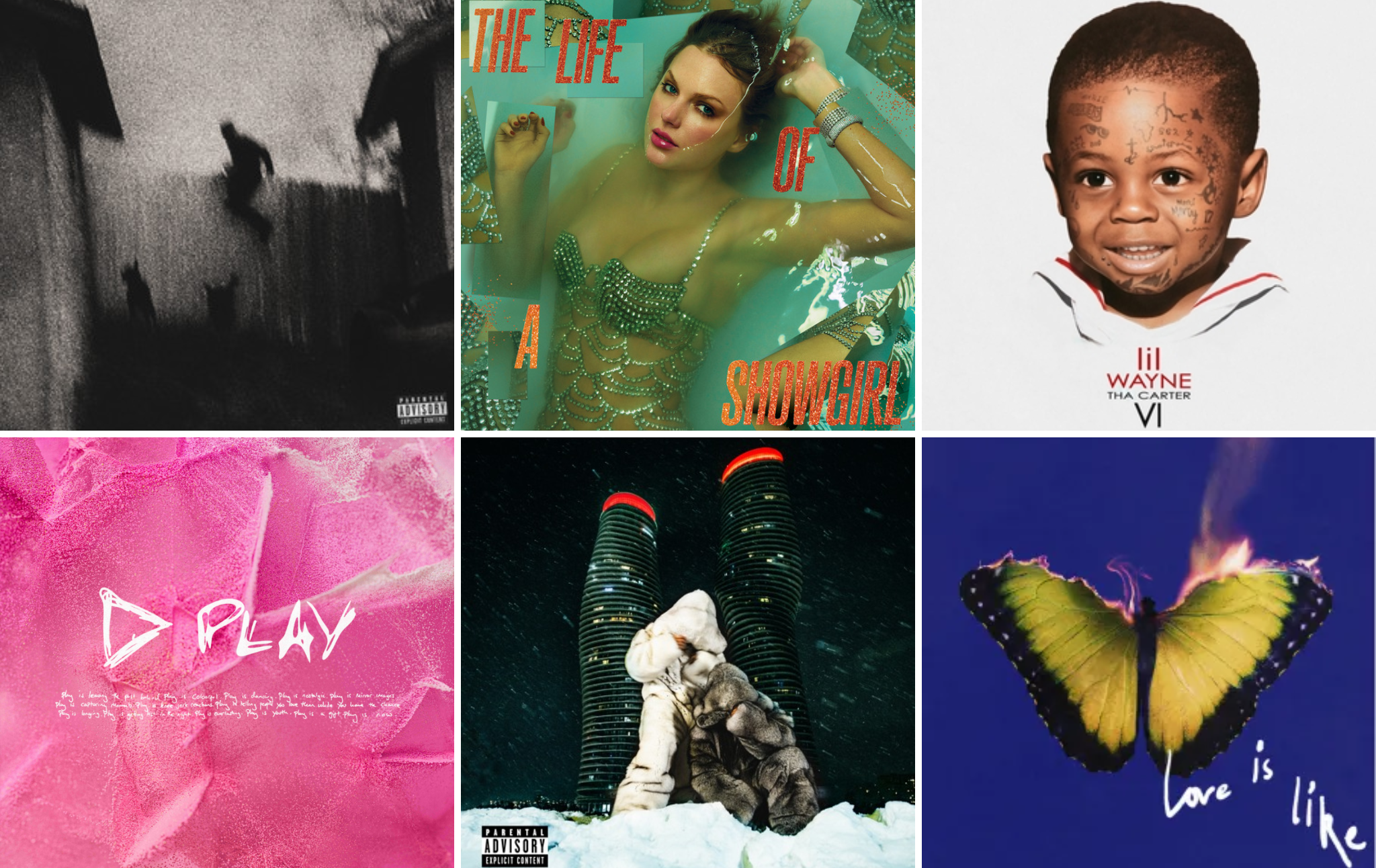

You know things have gotten bad when Taylor Swift’s millions of devoted listeners don’t even seem too interested in defending her latest project. “Production-wise, it was sound, but often felt generic—almost like something an AI could have churned out,” writes Natalie McGowan, a self-described “Swiftie,” in Style. (In fact, Swift did appear to use AI for the album’s visuals, if not the music.) “Even loyal, die-hard fans are questioning The Life of a Showgirl’s lyrics,” writes Abby Monteil in her review for Teen Vogue, and it’s easy to see why. Swift’s 2024 album, The Tortured Poets’ Department, started a noticeable slide in her writing—remember “You know how to ball, I know Aristotle / Brand new, full throttle / Touch me while your bros play Grand Theft Auto”?—but in 2025 it’s only gotten worse.

There are, to be fair, a few decent tracks on Showgirl; “Elizabeth Taylor” in particular is nice, and actually fits the album’s ostensible theme of vintage show business. But they’re drowned out by the bizarre, tasteless songs that have nothing to do with being a showgirl at all. There’s the quasi-diss track, “Actually Romantic,” where Taylor seems to be attacking fellow pop star Charli XCX without actually mentioning her by name. (Apparently Charli called her a “Boring Barbie,” or at least Swift heard someone else say she did. Which is, of course, reason enough to write an entire song.) There’s the goofy ode to Travis Kelce’s penis, “Wood,” which includes lines like “I don’t need to catch the bouquet / to know a hard rock is on the way” and “forgive me, it sounds cocky.” (Did Beavis and Butthead help write this?) The track sounds like Swift is trying to create her own spin on the more overtly sexual pop songs that have been big recently, like Billie Eilish’s “LUNCH” or Sabrina Carpenter’s “Bed Chem”—Carpenter also appears on the Showgirl album as a feature—but she doesn’t quite have their sense of irony or playfulness, so it just comes across as awkward over-sharing.

The worst aspect of the album, though, is the whininess. One of the least appetizing things on Earth is when fabulously wealthy people complain about how hard their lives are, and Showgirl goes back to that well on multiple occasions. On “Eldest Daughter”—which also seems derivative, this time of Hayley Williams’ recent song about being an eldest daughter—we’re treated to an extended whinge about seeing mean posts online:

Everybody's so punk on the internet

Everyone's unbothered 'til they're not

Every joke's just trolling and memes

Sad as it seems, apathy is hot

Everybody's cutthroat in the comments

And on “CANCELLED!”, whose title reads like a Trump tweet, we get an unironic complaint about “cancel culture,” at least two years out of date:

But they'd already picked out your grave and hearse

Beware the wrath of masked crusaders

Did you girlboss too close to the sun?

Did they catch you having far too much fun?

To point out the obvious, nobody has “cancelled” Taylor Swift, and it’s doubtful whether anyone could if they tried. By some estimates, she had a net worth of $2.1 billion in 2025, and sold more than 4 million copies of Showgirl, making it by far the top-selling album of the year. If anything, she’s the one who’s been in a position to “cancel” others, often releasing yet another variant of her album to boost its sales and block other artists from reaching #1 in the charts. (Altogether there are 38 different variants, some with bonus tracks, and it would cost $741 to collect them all.) So hearing someone that rich and successful complain about “trolling and memes” from the comfort of their private jet just grates.

Speaking of self-indulgent whining, let’s talk about Drake. Coming off a loss in his big feud with Kendrick Lamar, he released a comeback album of sorts, in collaboration with longtime creative partner PartyNextDoor. Now, there’s a blueprint for how to come back after losing a rap beef—literally. Jay-Z did it in 2002 with The Blueprint 2, after he lost so badly to Nas’s “Ether” that the word “ethered” permanently became slang for “taken down.” All you have to do is release a solid album with a few hits, sound confident, and you’re basically fine. That isn’t what Drake did. Instead, he put out a jumbled rap/R&B fusion project that manages to have neither compelling raps nor danceable R&B. It’s called $ome $exy $ongs 4 U, a title that’s embarrassing in itself, but serves as a useful warning sign for the cringe within.

Pitchfork critic Alphonse Pierre called $ome $exy $ongs “a desperate album from one of rap’s most notorious narcissists,” and he’s not kidding. Most of the songs revisit themes Drake’s already explored before, like pining after an ex in a vaguely creepy and possessive way (“Exfoliate that n—a that you with, he a scrub / Like I wanna know what's up, what happened to us?”). He complains that he has a lot of haters (“N—s want to see RIP me on a t-shirt like I'm Hulk Hogan”) and not enough friends (“Savage, you the only n—a checkin' on me when we really in some shit”), and he just generally feels sorry for himself (“I need a drink 'cause it's been a long day / Make it somethin' strong so I can float on this wave”).

The gripes are interspersed with endless references to champagne bottles, luxury cars, watches, jewelry, and so on; one of the tracks is just called “Crying in Chanel,” which doesn’t exactly inspire sympathy. It’s the kind of thing he could get away with, just about, on albums like Take Care when he was in his 20s and cared more about the rhymes themselves, and the kind of thing he largely avoided on projects like What a Time to Be Alive, his best work in recent memory. (It helps when you work with Future and not PartyNextDoor.) Now he’s 39, old enough that he shouldn’t really be complaining about haters and fake friends any more, and the whole schtick is just getting tedious.

Drake was always a little corny, though. It’s the downfall of Lil Wayne’s iconic Tha Carter series that really hurts. This year Wayne released Tha Carter VI, and it was so disjointed and weak that several reviewers wondered whether parts of it were AI. (It’s still unconfirmed that any actual vocals were, although like Taylor Swift, Wayne definitely used AI on his promo videos, which added to the suspicion.) Some of the creative decisions, though, are too weird to be anything but old-fashioned human bad taste. There’s a feature from country/rap crossover artist Jelly Roll, who doesn’t mesh at all with Wayne’s style; there’s a track where he inexplicably decides to rap over Andrea Bocelli singing “Ave Maria,” which similarly doesn’t pay off. There’s a tacky anti-Asian joke on “Bells,” which is just a worse remake of “Rock the Bells” by LL Cool J: “I don't smoke bunk, I only smoke that strong / Eyes tight like my name Wong-Ding-Ding-Dong.” (Oh look, Beavis is back.) But the most memorable element, in all the worst ways, is the beat on “Peanuts 2 N Elephants,” which sounds like a bouncing spring in a Mario game, combined with the repeated sound of an elephant’s trumpet, over which you can’t really hear Lil Wayne rapping. It really has to be heard to be believed, especially if you still remember Tha Carter III or the No Ceilings mixtapes fondly. They don’t even sound like the same person’s work.

But at least those albums are so bad, and in such weird and disparate ways, that they’re interesting to think and talk about. You can’t say that for every bad album. Ed Sheeran’s Play, for instance, got surprisingly little media attention when it came out in September, but maybe that’s because there’s so little to say about it. There’s no emotionally affective hit like “Shape of You” or “Thinking Out Loud” that’ll be played so much at weddings that everyone gets sick of it; just 13 tracks that are sort of there, like the music on the speakers in a carpet store. (The deluxe edition has 27, which is too many.) “When he sings that he feels ‘an overwhelming sadness / Of all the friends I do not have left,’ it just serves as a reminder of how literal Sheeran is as a songwriter,” writes critic Shaad D’Souza. Ouch.

It’s pretty much the same on Maroon 5’s Love is Like, which you might not have realized released this year; just worse retreads of stuff they’ve done before, with the exception of “Yes I Did,” a mildly disturbing song where Adam Levine is apologizing for cheating on a partner over a discordantly smooth, cheery melody with a lot of “yeah, yeah, yeahs.” Will Smith dropped a new rap album this year, for some reason; the only highlight was a track where he just said “I like pretty girls” over and over. And then there’s JackBoys 2, a compilation album from Travis Scott’s rap label. My phone says I’ve listened to it, but I couldn’t tell you anything about it, other than that GloRilla had a decent feature. As I say, it’s been a rough year.

Now, what do all these stinkers have in common? There are, believe it or not, a few commonalities. One is that most of the artists have been famous, wealthy superstars for a decade or longer, and they’ve clearly run out of good ideas for songs. Their best subject matter was burned up on their first few albums, and now they’re either shamelessly recycling (Sheeran, Drake, Maroon 5) or making wild stabs in new directions that don’t really work (Swift, Lil Wayne). In either case, it would probably be for the best if they just retired gracefully, or at least took a few years off until they have an actual idea. But they won’t, because they’ve gotten used to raking in the money and attention, and their labels want them to keep cranking out albums. In some cases, they can be contractually obligated to do so, whether or not the albums are any good.

The other factor is the self-absorption that so often comes with fame. It’s striking how all these albums are narrowly, solipsistically about the artist themselves: their love lives, their personal spats with other artists, whether they’re sad that day, what kind of clothes they wear, what cars they drive, what drugs they take. There’s an entire planet full of people, places, and things to write songs about outside yourself, from political topics (none of these artists really do protest songs, other than Lil Wayne in 2006) to concept tracks where you tell a story or take on another persona. But when your full-time job is “celebrity,” you’re constantly surrounded by people who only want to talk about you, and you don’t have anyone in a position to tell you “no, that song idea sounds awful.” You become more a brand than a person, and your talent vanishes further and further down your own navel as you gaze at it.

But it’s the economics of streaming platforms that are really against you. Despite being wealthy and famous, most of these artists aren’t making great money on the music itself, at least not on a per-unit basis. Notoriously, platforms like Spotify pay almost nothing to musicians—”somewhere between $0.003 and $0.005 per stream,” by one estimate. (In fact, if your song has fewer than 1,000 streams, Spotify now pays literally no money for it, which means roughly 60 percent of tracks on the platform have been demonetized.) The tradeoff is that the apps make listening to music easy and frictionless, compared to buying a physical CD like we all used to do, so artists can make up the difference in volume. They get less money per listener, but more listeners than ever before, thanks to a global internet that reaches far beyond any radio network in the 20th century. But in practice, that means only a small class of mega-stars, with streams in the millions and even billions, can make decent money off the streaming model.

In order to do so, they’re incentivized to release lots of music, regardless of quality, because two bad albums with 27 songs apiece will generate more streams and more cash than one good album with nine songs. They’re pressured to release short, catchy songs that are likely to go viral on TikTok and Instagram, and avoid longer, more complex ones. In a recent interview with critic Anthony Fantano, R&B singer Summer Walker revealed that she had to fight her label to include any tracks longer than three minutes on her most recent album. Artists self-censor, avoiding controversial topics so they can get both Democratic and Republican money. And all of this is made vastly worse by the consolidation of corporate power, as “three record labels—Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Music Group—control almost three quarters of the global recorded music market,” while Spotify, Apple, and YouTube dominate streaming itself. Artists have less leverage and creative control, compared to the corporate office. The result is an industry that creates Pasteurized Processed Music Product, which has about as much in common with good music as Velveeta does with Camembert.

None of this is inevitable. There are growing calls for a boycott of Spotify, both because they pay artists next to nothing and because the corporation has been hosting recruitment ads for ICE and promoting AI music on its app. I’ve been boycotting Spotify since Day One, although admittedly that’s mostly because I hate the app layout. There are other alternatives, like Tidal, that pay moderately more; better still, you can actually buy albums, either in lossless digital form or as CDs or vinyl records. Apart from the labor situation, the audio on streaming apps is compressed in all kinds of ways; compare a CD of a song to the same song on YouTube Music, and the disc wins every time. Nothing says you have to consume music the way Big Tech would prefer.

That’s just the consumer side. Artists can assert themselves over the financiers, too. It’s notable that one of the best albums of the past year, Let God Sort ‘Em Out, is the product of a fight Pusha T and Malice—collectively, the Clipse—had with Universal Music Group. For complicated rap-beef-related reasons, the label had demanded that they cut Kendrick Lamar’s feature from their album, only for them to refuse, pay “seven figures” to get out of their contract, and release the project independently. That’s one group composed of two guys, and they stood up to one of the biggest corporations on Earth.

But they were only able to do so because they had money and resources, and as long as artists operate on their own, only those with serious money will be able to stand up for themselves in that way. Much more is possible if many of them stand together. When I interviewed Fantano last month, he said the real solution is for musicians to unionize, the way workers in the movie industry have, and demand more control over their own industry. That’s exactly right, because the root of the whole problem is the corporations’ demand for ever-greater profit. Maybe with a strong SAG-AFTRA style union, we could get a completely different set of economic incentives working. We might get fewer albums every year, but more of them would actually be listenable. If it stops Taylor talking about Travis’s wood and Lil Wayne saying “wong-ding-ding-dong,” it would be worth it.