How Corporations Convinced America that Litter is Our Fault

The "Keep America Beautiful" campaign urged Americans to pick up their trash—so that companies could keep producing it.

This morning, while sitting at a red light, I watched as the person in front of me rolled down the window of their Lexus, stuck out an arm, and flung a greasy McDonald’s bag filled with garbage and empty soda cans onto the sidewalk. Instinctively, I slammed my horn with one hand and made the universal “what the hell?” gesture with the other. They did not respond. For a moment I considered stepping out of my car and scooping the strewn Egg McMuffin entrails into a pile to hand back to them; then I remembered that I live in America, where people have guns, and I decided this wasn’t really a situation worth escalating. The light turned green and the driver sped off—laughing maniacally and slurping ketchup from each of their fingers, I assume—while I fumed.

Few small acts seem to breach the social contract like littering. Dumping your garbage on the ground is illegal, technically, but it’s treated more like a character indictment than a crime. If I saw someone shoplifting in Walmart I’d look the other way; if I saw them drop a handful of wrappers in the aisle, I’d ask them why they’re better than the custodian who has to pick it up. Any old Joe Schmoe can rob a bank, but it takes a real scumbag to leave trash all over a hiking trail. As a society, however, we didn’t always feel this way.

Littering only became a real public issue in the States after World War 2, when disposable containers first began to flood the market. It only became a real taboo 20 years later, and not because tree-hugging hippies felt strongly that Americans must hold their garbage until they find the nearest dumpster! When our rivers, forests and sidewalks began to overflow with trash, environmentalists went straight to the source, demanding that corporations put a stop to single-use packaging. But companies didn’t like that idea, shockingly enough, and so they created their own campaign: Keep America Beautiful, which placed the blame on the individual. If industries could convince Americans that litter was a personal failing, then no one would ask where it came from in the first place.

Before we get into the greenwashing of single-use containers, it’s worth explaining what the world looked like before they existed. Imagine, for a second, that you’re a 12-year-old boy in 1930 (preferably wearing a newsie cap and fresh off your shift on the street corner yelling “EXTRA, EXTRA, READ ALL ABOUT IT!”). The Yankees just won, it’s a beautiful day, and you decide to treat yourself to a soda. You walk down to your local corner store and buy a bottle of Coke for five cents.

After downing the whole thing in one gulp, you belch the alphabet and return the empty bottle to the cashier. He gives you two cents back—a full 40 percent of the total price—and keeps the glass. You purchased the liquid, not what it came in. Had you kept the bottle, or shattered it playing hopscotch or whatever, you’d be forfeiting a significant chunk of change. The shopkeeper then collects the returned bottles in a crate until it’s time to send them away to be refilled. You tip your adorable newsie cap to him and skip blissfully into the street, thankful that you only have to worry about polio and not microplastics. (Okay, roleplay over.)

Back then, Coca-Cola was basically just a syrup factory that operated a local franchise system. Independent local bottlers purchased the syrup, mixed it with carbonated water themselves, then filled glass containers to distribute to nearby stores. Bottles could be used up to 50 times, and once they finally broke, they could be melted down again. The earliest data on the efficacy of this system is from the ‘40s, and it shows over a 95 percent return rate on bottles.

But when World War 2 arrived, the military had no time for reusing materials. American soldiers overseas were given K-rations: individually packaged, ready-to-eat meal boxes designed to be eaten and tossed, with no practical way to return the empties (these became an early prototype for frozen TV-dinners). Across the country, plastic production was also ramping up dramatically for use in parachutes, electrical insulation, nylon cords, and other military products, while lightweight aluminum cans replaced heavy glass bottles for shipping drinks. To transport these goods, the U.S. Army formally created the first “Logistic Units” in 1942–43 to coordinate shipping and packaging across the globe—a precursor to modern supply-chain systems, which prioritize efficiency over reuse. (Think about when you try to return something to Amazon and they just give you a refund, without asking for the product back, since the item is even cheaper than the cost of shipping.)

During the war, America perfected mass production, and once it was over, we had all of these state-of-the-art factories just sitting there—ready to pump out cheap, light-weight, disposable products. We had more plastic than we knew what to do with. Nylon, no longer needed for rope, became women's stockings and lingerie; plastic film, once used to protect sensitive military equipment, was now marketed for wrapping up last night’s lasagne; styrofoam, used for insulation and flotation devices, became disposable cups and takeout containers.

Meanwhile, the expansion of the U.S. highway system and automobile industry meant that Americans were on the go; they wanted to drive down Route 66 eating cheeseburgers from a bag and gulping soda from a can, preferably without a seatbelt, and preferably tossing it all out of the window when they were done.

A 1955 Life article dubbed this the era of “Throwaway Living.” A full-page photograph in the magazine features a grinning, white-bread American family beneath a flurry of disposable items: frozen food containers, paper napkins, diapers, foil pans, paper cups, and more. “These objects flying through the air in this picture would take 40 hours to clean—except no housewife need bother,” the page reads. “They are all meant to be thrown away after use. Many are new; others, such as paper plates and towels, have been around a long time, but are now being made more attractive.”

But there was one quickly growing problem with the disposable revolution, when combined with the mass-production of cars. More Americans on the freeways meant more trash piling up on the side of the road, but it also meant more people could see it. The public valued convenience, but they valued beauty too. Perhaps sensing a future PR problem—in that much of the unsightly garbage bore their logos—the American Can Company and Owens-Illinois Glass Company established the “Keep America Beautiful” nonprofit in 1953. Alongside leaders from major beverage firms like Coca-Cola and Anheuser-Busch, KAB ran local campaigns that preemptively framed pollution as an individual issue.

A 1954 issue of National Parks and Conservation Magazine described the organization’s founding:

Manufacturers of bottles, cans, candy wrappers, facial tissues and other products that are strewn along the paths of the motoring and camping public recognize their responsibility to help correct the untidy habits of the American people.

It wasn’t a structural problem, you see, but a widespread moral failing. Keep America Beautiful soon partnered with the Ad Council to popularize the idea that individuals were responsible for maintaining the environment—but Americans weren’t quite aware yet of the magnitude of the problem. Then, Rachel Carson published her groundbreaking 1962 expose Silent Spring. The shocking report on the effects of pollution and pesticides on wildlife prompted a widespread ban of the chemical DDT, and led Americans to take a closer look at the human impact on the natural world.

By the end of the decade, Americans no longer needed a book to tell them something was wrong—they could see it. In January of 1969, an offshore oil rig off the coast of Santa Barbara blew out, spilling hundreds of thousands of gallons of crude into the Pacific Ocean. Beaches were coated in black sludge and birds washed ashore soaked in oil, while televised images of the disaster ran nightly. Just a few months later, the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, so saturated with industrial waste that it barely resembled water, caught fire (again). Rivers had burned before, but this time the photographs went national.

Public outrage followed swiftly. In April 1970, millions of Americans took to the streets for the first Earth Day, demanding accountability. One of the protests included 1,500 people dumping Coca-Cola cans and bottles at the company’s headquarters. The federal government acknowledged the waste problem, with one White House science advisor saying “the social cost [...] of these indestructible items is tremendous,” while President Richard Nixon lamented the country's “new packaging methods, using materials which do not degrade.”

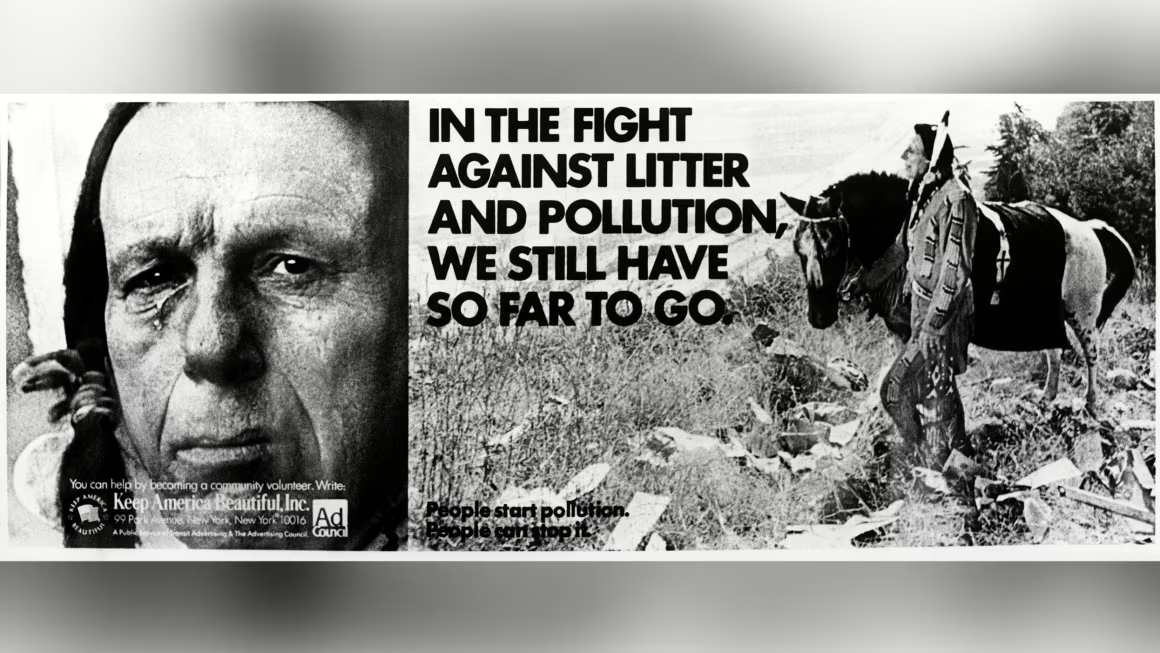

But Keep America Beautiful already had a plan in place. On the second Earth Day in 1971, the organization released their iconic “Crying Indian” PSA.

The one-minute TV spot shows a Native-American man, costumed with two braids and feather tucked behind his ear, paddling a canoe downriver; as the camera zooms out, an ominous backdrop of oil rigs and factories appears behind him. He pulls the boat ashore, surrounded by styrofoam and wrappers, and solemnly climbs up the bank to the side of a freeway. A passing motorist tosses a fast food bag out the window, the strewn french fries and wrappers landing across the Indian’s moccasins. “People start pollution,” a voice over declares. “People can stop it.” A single tear rolls down his cheek.

The one-minute TV spot shows a Native-American man, costumed with two braids and feather tucked behind his ear, paddling a canoe downriver; as the camera zooms out, an ominous backdrop of oil rigs and factories appears behind him. He pulls the boat ashore, surrounded by styrofoam and wrappers, and solemnly climbs up the bank to the side of a freeway. A passing motorist tosses a fast food bag out the window, the strewn french fries and wrappers landing across the Indian’s moccasins. “People start pollution,” a voice over declares. “People can stop it.” A single tear rolls down his cheek.

The campaign was a hit. “TV stations have continually asked for replacement films” of the commercial, said one Ad Council official, “because they have literally worn out the originals from the constant showings.” It didn’t matter that the “Crying Indian” character—played by an actor who went by the name Iron Eyes Cody—was actually an Italian-American named Espera DeCorti, or that actual Native Americans were hosting their own concurrent protest against the degradation of their land.

Framing litter as an individual failing was incredibly successful. In the coming years, several bills that tried to address the root of the issue—like the Nonreturnable Beverage Container Prohibition Act, which would ban single-use containers’ shipment and sale in interstate commerce—were shut down. Leaders across the world followed the industry’s party line, according to The Guardian:

In 1988, the year global plastic production pulled even with steel, Margaret Thatcher, picking up litter in St James’s Park for a photo op, captured the tone perfectly. “This is not the fault of the government,” she told reporters. “It is the fault of the people who knowingly and thoughtlessly throw it down.”

Today, Keep America Beautiful likes to tout progress. According to its 2020 National Litter Study, “visible litter along U.S. roadways is down about 54 percent” since 2009, and the long-running comparison to 1969 shows an even larger cumulative reduction. The study also notes declines in a handful of key product categories like fast-food packaging and soft-drink containers, framing this as evidence that “littering” is decreasing. Of course, that’s only the waste we see. According to the EPA, total municipal solid waste has increased from about 88 million tons in 1960 to nearly 292 million tons in 2018, an increase of roughly 230 percent—with packaging and containers alone making up a significant portion. When it comes to waste: out of sight, out of mind.

So yes, the person in the Lexus this morning was being an asshole. I’d argue they still deserved the horn, the gesture, and maybe even a sloppy pile of Egg McMuffins delivered through their open window. But it’s not like Americans suddenly forgot how trash cans work. Instead, we were trained, systematically and effectively, to see littering as a personal failure rather than the predictable outcome of an economy built on disposability. If litter feels like a character flaw, that’s because it’s the most successful piece of packaging that the container industry ever produced.

.png?width=352&name=r-cohen%20(1).png)