Not every film about “cowboys and Indians” is as reactionary as the genre’s reputation might suggest.

There is not a strict dichotomy between conservative Westerns and left-wing ones: a film that is progressive on one issue may be reactionary on another, and may be ambiguous on a host of issues, whether through thoughtlessness or anxious vacillation. But there is a thread running through so much of the genre—sometimes front-and-center, sometimes only glimpsed—that the hand-me-down cultural collage of Manifest Destiny and masculine individualism omits. “It is at least as plausible to see Westerns as fundamentally anti-establishment, against the rich and powerful and in favor of the poor and weak,” Edward Buscombe writes in his excellent book about the classic Western Stagecoach.” The Western teems with corrupt sheriffs, arrogant and tyrannical landowners, grasping and cheating bankers, sadistic and blinkered martinets. Even on the racial issue, where the depiction of Indians makes it vulnerable, one might venture that there is more explicit anti-racism in the Western between 1940 and 1970 than in any other Hollywood genre. Only to the charge of sexism is one bound to enter a plea of guilty as charged.” (Though I think that if Buscombe did want to plead not guilty, a good lawyer could mount a serviceable defense on that one, too.)

“From a distance, it’s very easy to view the Western genre as a great abstract swirl of cowboys and Indians, the proud Cavalry vs. the mute savages, a long triumphal march of Anglo-Saxon humanity led by John Ford and John Wayne brought to a dead halt by The Sixties,” Kent Jones writes for Film Comment. And yet, “Up close, one movie at a time, the picture is quite different.”

So, let’s look at some Westerns, up close, one movie at a time.

Sergeant Rutledge (1960)

When Orson Welles was once asked about his favorite filmmakers, he replied, “I prefer the old masters, by which I mean John Ford, John Ford and John Ford.”

Born Jack Feeney to Irish immigrants in Maine towards the end of the nineteenth century, Ford has as good a claim as anyone for the title of greatest American filmmaker. (A pretty strong claim for the greatest American artist in any medium, too.) Though he worked in many genres—managing to direct a Shirley Temple vehicle and a searing adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath within short range of each other—Ford is inextricable from the Western. So much of what Westerns are as a film genre, how they look and feel and move, goes back to Ford. His own complexity is that of the Western in microcosm.

There are two major narratives about the arc of John Ford’s politics. One, as Eileen Jones outlines, is that while Ford initially indulged in the supremacist myths of America and of the West, his “later questioning of his own beliefs, instigated by the Civil Rights movement” led to “his later, darker, more troubling film-noir-ish Westerns.” The other is that, as a young man, he was broadly of the political left, identifying as a social democrat, supporting the New Deal and collaborating with Irish communist Liam O’Flaherty (Ford won his first of four directing Oscars for his film of O’Flaherty’s novel The Informer), before drifting to the right, supporting Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon in their presidential campaigns. Despite being opposite in every way, both stories are somewhat true, and I have no desire to shave off Ford’s sharp edges by presenting only one or the other. Though Ford’s personal politics seem to have moved to the right, the shift in his films isn’t best understood in terms of left and right, but a movement among a different axis.

Ford’s films have a progressive spirit from the start. Stagecoach, his first Western of the sound era, treats the largely faceless Apache as a generic threat, but its true villains are a banker outraged at the concept of bank inspectors who talks about how what we need is a businessman for president, and a Cavalry officer’s wife who is cruel to a sex worker being run out of town by the Law and Order League. That sex worker (Claire Trevor) is one of our heroes, falling in love with escaped convict the Ringo Kid (John Wayne, still young and fresh-faced even after a decade of slumming it in B-pictures). It’s a film that aligns itself with underdogs and outcasts, buzzing with New Deal optimism. Along with Young Mr. Lincoln, released the same year, it is the last pure expression of Ford’s American idealism.

From there, Ford’s Westerns don’t drift left or right, but—particularly from World War II onwards—they begin to revise and interrogate their own mythology, and become critical of both self and state. As early as 1948, a film like Fort Apache has Captain York (John Wayne again) flat-out say that the only reason there is unrest in the Apache reservation is because the U.S. government and army refuse to treat them with any respect, dignity or honor. “Whiskey but no beef; trinkets instead of blankets; the women degraded; the children sickly; and the men turning into drunken animals. So Cochise did the only thing a decent man could do. He left,” York tells his commander, Lt. Col. Thursday (Henry Fonda). “Took most of his people and crossed the Rio Bravo into Mexico[…] rather than stay here and see his nation wiped out.” It falls on deaf ears: the final act sees Thursday lead a hopeless charge against the Apache for no reason at all other than because he wants the glory of battle. The Apache kill dozens of white American soldiers, but in the narrative, they are completely justified: the U.S. broke the treaty first. By his final Western in 1964, Ford is totally unflinching: Cheyenne Autumn chronicles the Northern Cheyenne Exodus, as Little Wolf (Ricardo Montalbán) and Dull Knife (Gilbert Roland) lead their people out of the Indian reservation in Oklahoma and north to their ancestral homeland. At one point, a German soldier repeatedly says he’s “just following orders” as he corrals the Cheyenne into a warehouse without food or heat. It’s hard to miss the point.

Ford “relentlessly dramatized, in his Westerns, the mental and historical distortions arising from the country’s violent origins—including its legacy of racism,” Richard Brody writes for The New Yorker, “which he confronted throughout his career, nowhere more radically than in Sergeant Rutledge.” Released in 1960, Sergeant Rutledge treats its Apache fighters as the same kind of generic threat as they are in Stagecoach, contrasted here not with outcasts and outlaws, but a heroic cavalry officer—evidence, if there was any, of Ford’s reactionary turn. Except that Rutledge, the heroic cavalry officer of the title, is the first sergeant of an all-Black regiment, played by Woody Strode in a rare leading role. It’s a courtroom drama in which Rutledge is put on trial for the rape and murder of a white girl, with the main narrative playing out in flashback. In those flashbacks, we see the girl’s body being found, Rutledge fleeing when he’s accused, and another Cavalry officer, Tom Cantrell (Jeffrey Hunter), chasing Rutledge down to bring him back to trial. As each witness speaks in turn, they are bathed in light while the rest of the courtroom plunges into darkness. In most films, Hunter’s role as Cantrell, the white counsel for defense, would be at the centre—Sergeant Rutledge was released the same year as Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird, and two years before its film adaptation starring Gregory Peck—but here, Strode is indisputably the protagonist. He has the charisma of a born movie star, the physique of an athlete, and the emotional depth of an actor’s actor. It’s a crime he wasn’t the biggest star on Earth.

Despite its flashback structure, Sergeant Rutledge—much like Martin Scorsese’s The Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)—does not treat its central “mystery” as a mystery. State actors only treat the facts as non-obvious because racism is a built-in feature of the system. Just as it is obvious who is murdering Osage women in Flower Moon and why, it is obvious that Rutledge did not rape and murder the white girl. He is a hero at a mythic scale. He stands tall against the horizon while his soldiers sing a ballad about the legend of a giant, ideal Black soldier, Captain Buffalo, and he is myth made flesh. His almost perfection doesn’t make him anodyne or inhuman, but serves to underscore the commonplace paradox of his life. Rutledge is a proud Black soldier: totally clear-eyed in seeing how this country does not love or value or respect him, his troops, or those who look like them, and fights for his country anyway. He has no illusions about white racism: when hiding from Apache warriors, he tells Mary (Constance Towers) that if anyone comes, they can’t be seen together.

“That's nonsense! We're just two people trying to stay alive,” Mary tells him.

“Lady,” he replies, “You don't know how hard I'm trying to stay alive.” He might have a hole in his gut from an Apache arrow, but it’s white violence he has to fear.

Rutledge sees America as it is, but strives for—embodies—the dream of what America should be. But that’s not enough. He may be a mythic ideal American soldier, but he’s still Black. And if the prosecutor, the townspeople, and the judge’s wife—baying for a hanging with her posh lady friends in the gallery—get their way, this will be a show trial preceding a lynching. If the rest of the court aren’t portrayed as overt white supremacists, that is damning in its own way. That they would participate in such a manifestly racist proceeding without hate in their hearts demonstrates that racism is not a matter of bad individuals, but a bad system. It’s no wonder Rutledge’s first instinct is to run.

Cantrell asks if this won’t haunt him forever if he doesn’t return to face the charges. “We been haunted a long time. Too much to worry,” he says. “Yeah, it was all right for Mr. Lincoln to say we were free—but that ain’t so. Not yet, maybe someday, but not yet.” He still carries his manumission papers with him, declaring him a free man: they are found among his possessions when he is taken into custody for trial. The juxtaposition of Hunter reading the papers aloud over the image of Rutledge in handcuffs is as searing a critique of the 13th amendment—which abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime”—as I’ve seen in movies that side of Ava DuVernay’s documentary on the subject.

The film never pities Rutledge, never treats him as a victim who exists for white people to showcase their morality. Instead, it shakes with fury. Strode carries himself with a defiant dignity, beneath which roils a torrid mix of fierce loyalty, righteous anger, sincere pride, self-protective wariness, profound trauma, and utter gallantry. He is exceptional, but he is not an exception. A number of affecting performances from Black actors in supporting roles round out the film’s anti-racist critique as not dependent on Black perfection. An old soldier (Juano Hernandez) is asked his age in the witness booth, and he answers, “I don't rightly know.” When the prosecutor says, “You mean you don't even know your own age?,” he’s trying to dismiss him as an unreliable witness, and more, a fool.

Then he explains: “I was slave-born. And I saw the first steamboat come down the Mississippi River. At least my mammy said it was the first, and she was holding me up to see.” That makes him over seventy. It is a jarring reminder of how, along with so many other things slaves were denied, they were deprived of self-knowledge, of personal history—a fact that echoes down through their descendants.

Another soldier from Rutledge’s regiment is killed in battle with the Apache. As he dies in Rutledge’s arms, he wonders why they got involved in this white man’s war. “It ain't the white man's war,” Rutledge tells him. “We're fighting to make us proud.” You wonder who he’s trying to convince.

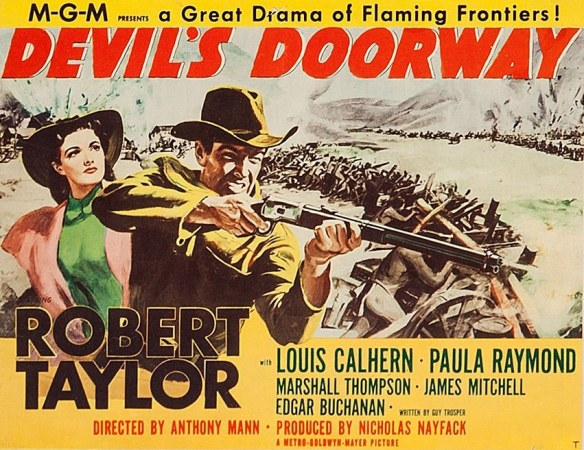

Devil’s Doorway (1950) and Little Big Man (1970)

A classic set-up for a Western is some small homesteaders versus the big ranchers. The homesteaders are poor, often immigrants, and stubbornly trying to make a new life for themselves out west by farming a small holding. The big ranchers are a wealthy cabal with vast lands that they are unwilling to share, and are fine with destroying the homesteaders’ crops to get a bit more square-footage for their cows. Often, as in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the ranchers oppose statehood, or anything else that might involve the homesteaders getting a say in how the territory is run. The ranchers have the local authorities in their back pocket—in Heaven’s Gate (1980), they employ a whole death squad—while the homesteaders, in Shane (1953) and The Westerner (1940), might scrounge together one gunfighter between them. You side with the homesteaders every time, and you’re supposed to.

Except in Devil’s Doorway (1950). In that film, the big landowner is a hero, and that any homesteader thinks they can take a blade of grass away from him is an outrage. This total reversal of sympathies is down to one simple difference: the big land-owning family are Shoshone, and the homesteaders are colonizing their ancestral homeland.

Lance Poole (Robert Taylor) comes back to Medicine Bow, Wyoming with a Medal of Honor and a heart full of hope. Fighting for the Union army in the Civil War, he saw a different future for America: “The country is growing up. They gave me these stripes without testing my blood,” he tells his dying father, “I led a squad of whites, slept in the same blankets and ate from the same pan. Held their heads when they died. Why should it be any different now?”

“You are home,” his father answers, “You are again an Indian.”

It’s true. Though he initially receives a warm welcome from the white townsfolk, they resent his family’s lands. Their previously passive prejudice is inflamed by a white supremacist lawyer, who uses the homesteading laws to hand Lance’s property, piece by piece, to white settlers. The white doctor refuses to treat Lance’s father, and he dies. Lance is barred from the saloon where he was welcomed as a war hero, a “No Indians” sign now hanging on the wall. He finds his own lawyer, Orrie Masters (Paula Raymond), who is herself viewed with suspicion as an educated professional woman.

The laws are cruel, and there is little way around them. Lance can’t homestead on his own land because—despite his war record—he is not an American citizen, but “a ward of the Government.” He can’t buy his land back later from white men who homestead on it, either, because it’s against the law. As the film goes on, Lance digs his heels in further and further, adopting (or re-adopting) traditional dress and manner, rejecting more and more of his once-proud Americanness and embracing a willingness to fight the army he once fought for. Though Masters clearly thinks the law is unfair, her liberal anti-racism is revealed as only surface-level when the stakes escalate. There is no white savior narrative, because the law is written to disallow the possibility, and because ultimately, she doesn’t want to save the day. Deep down, she doesn’t think he’s truly entitled to keep his land, she thinks he’s throwing a tantrum about being asked to share. But for Lance, the threat is existential. This rift is part of why the erotic frisson between them, present throughout the film, doesn’t come to a head. She might think he should get served in the saloon, but she doesn’t understand that this whole country is built on stolen land.

It is unfortunate that Lance—a shortening that doubles as a whitening of his Native name, Broken Lance—is played by a white actor like Taylor, but it also needs to be placed in the broader context of Hollywood racism. The Hays Code—the prevailing censorship rules to which the major film studios subscribed—forbade, amongst other things, “miscegenation,” and though it was somewhat up to interpretation whether this applied specifically to relationships between Black and white people or any kind of interracial relationship, Lance’s white love interest made it much less likely that the part would be given to an actor of color. Westerns more broadly have tended to cast Mexican actors, or darker-skinned Italians, as Native Americans. Even decades after the death of the Hays Code, white actors continued to play characters of color, perhaps especially Indigenous people, in movies and on television. Johnny Depp played Tonto in The Lone Ranger (2013). Emma Stone played a woman who was part-Hawaiian, part-Chinese in Aloha (2015), for which she apologized. Kelsey Asbille, who played one of the main Native characters on Yellowstone, has been publicly criticized by the Eastern Band of Cherokee for claiming to be part Cherokee. Not to mention full-time “pretendians” like Iron Eyes Cody, who posthumously turned out to be Sicilian. All of this is racist, and none of it is acceptable. It is also an ingrained part of over a century of Hollywood casting. I would rather live in an alternate universe where an Indigenous actor played Lance in Devil’s Doorway. But in the universe I live in, Devil’s Doorway is still one of the most harrowing depictions of someone realizing America is a false god yet put on screen.

Characters who move between Native and white worlds—and the friction that usually accompanies that back and forth—come up often in Westerns, though they are usually white characters who have some connection to an indigenous nation. Sometimes—as with, on either end of the tonal spectrum, Buster Keaton in The Paleface (1922) and Kevin Costner in Dances with Wolves (1990)—it’s a white person who a tribe adopts as their own because he has somehow proven himself distinct from other white people. Sometimes, as in Two Rode Together (1961), racist white society cannot accept white captives who have been returned, because their whiteness is now perceived as deformed or defective after living among the Comanche. Most interesting of these, however, are Westerns in which a white person is raised in a Native nation. In Hombre (1967), Paul Newman plays a white man who was raised Apache. Most famously, Dustin Hoffman is raised by the Cheyenne in Little Big Man (1970). These characters are indistinguishable from Native Americans in all of their cultural, emotional and familial ties, but not perceived as such—at least, unless they open their mouths at the wrong moment.

In Little Big Man, Hoffman plays Jack Crabb, who at one-hundred-and-twenty-one recites his life story to a historian. As a boy, his family are killed by the Pawnee, but the Cheyenne adopt him as their own. He is raised by Old Lodge Skins (Chief Dan George, for once an actual Native American actor), the tribal leader, who he calls Grandfather. He earns the name Little Big Man after he goes through a Cheyenne coming-of-age ritual. Throughout his life, Jack moves between Cheyenne society and white society, witnessing an improbable swath of history like the Forrest Gump of the Old West. He gets to be a gunslinger called the Soda Pop Kid, a snake oil salesman, and the town drunk of Deadwood. He was pals with Wild Bill Hickok and survived the Battle of Little Bighorn.

It’s a story about America in a broad, sweeping sense, poking fun at American pop history and the Western genre, but it is very specifically and devastatingly a story about the genocide of Native Americans. Jack serves for a time in Custer’s 7th Cavalry, but is shocked and disturbed by their slaughter of women and children and runs away. As with Soldier Blue, released the same year, Little Big Man’s depiction of American violence was interpreted in part as an allegory for the Vietnam War. With a few decades’ hindsight, “allegory” seems too narrow a way to conceive of that connection—if the Washita Massacre reminds you of My Lai, it is less that the West is being used as a backdrop to talk about Vietnam than it is history rhyming. Americans never really reckoned with what they did to the Native Americans, and in Vietnam—and in the Philippines, Haiti, Korea, Iraq and Afghanistan—they got back to their old tricks. When he returns to the Cheyenne, Jack asks Old Lodge Skins—now blinded by a white soldier—if he hates the white man, and it’s not a plea for his own innocence, but a plea for his grandfather to embrace the same rage he feels in his own heart. Old Lodge Skins tells him that the Cheyenne “believe everything is alive. Not only man and animals, but also water, earth, stone… But the white men, they believe everything is dead. Stone, earth, animals, and people. Even their own people. If things keep trying to live, white man will rub them out. That is the difference.”

In a stroke of genius, Little Big Man translates the Cheyenne’s word for themselves as “human beings.” It’s a small touch that asserts the humanity that white society would deny them. The white men in the film—Little Big Man excepted—contort their souls with racism and violence until they become grotesque facsimiles of humanity, like monsters in human skin. It’s the Cheyenne who are human beings, who seem capable of human feeling. “There is an endless supply of white men,” Old Lodge Skins says, “But there always has been a limited number of human beings.”

The Ox-Bow Incident (1943)

If Westerns have one theme, it’s justice. What it is and how to get it. Perhaps nothing is more fundamental to the Western as a genre than being on the precipice of lawlessness: the West as a place on the edge of the world where all the structures of the modern state haven’t yet reached, where the only law is the law of the gun. It is freedom and destruction, and it is always already ending, the oncoming spectre of modernity just around the bend. It is this central idea that allows the Western to be reinterpreted in other settings and other forms: in samurai films, in space operas, in films about the Irish Famine or colonial Tasmania or the Russian Civil War. This question of justice means that Westerns, more than many genres, are political—not in the noisy, reactionary way you might assume, but in a range of complex configurations.

Written by Carl Foreman before he was blacklisted from Hollywood, High Noon (1952) is an overt critique of McCarthyism. John Wayne turned down the lead role because he thought it was un-American. The role of Marshal Kane instead went to Gary Cooper. He’s going to be attacked by a group of outlaws arriving on the midday train. Not a single person in town will stand up for Kane despite this obvious wrong being done to him, and he must decide whether to fight or flee. In his book Wild West Movies, Kim Newman contrasts the “eerily neat and civilized” town and the “gutlessness, self-interest and lack of backbone exhibited by its inhabitants”—a perfect picture of 1950s Middle America, all white picket fences and social conformity, unwilling to risk an orderly life for the possibility of a just one. The historical remove and genre trappings of the Western allowed High Noon to speak on contemporary politics in a way dramas set in the present are often curbed from doing. Like science fiction or horror, Westerns have a degree of distance from current events that allows more strident political commentary to sneak in, and even more so because of the genre’s inherent interest in justice and the law.

The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) is about a lynching. Henry Fonda and Harry Morgan play a couple of drifters who land into town right before it’s announced that a local rancher named Larry Kinkaid has been murdered. The townspeople form a posse to track down the murderers, on strict notice from the town judge to bring them back for trial. But when they discover three men in the Ox-Bow Canyon with apparently stolen cattle, bringing them back to stand trial starts to sound a lot less attractive than hanging them at dawn. As in 12 Angry Men a decade later, Henry Fonda tries his best to plead for the accused’s innocence. But the Ox-Bow Canyon isn’t a jury room, and nobody here is compelled to listen to him.

It’s one of the best films ever made, so good that it’s weird that we aren’t all talking about it all the time. It's only seventy-five minutes long, but incredibly rich: it feels longer than it is, in the best kind of way. I don’t know how it manages to fit in a whole subplot about a cruel army major’s disappointment in his gay son. (They don’t say that he’s gay, because it’s a Hollywood movie in 1943, but I know what I saw.) The bulk of the film agonizes over this one long night of debate and bloodlust, giving us dozens of moments when the crowd might decide against doing this evil thing so that it hurts that much more when they do it anyway. Although it’s not about lynchings as racial violence—two of the men are white, the other is Mexican—it is keenly aware of how the particular horrors it examines affect Black Americans in particular. A Black man (Leigh Whipper) talks about the trauma he still carries from his brother being lynched when he was a kid. He says he never knew if he did what he was accused of, but—to any audience with the slightest knowledge of the history of U.S. racism—there is little doubt that he did not.

The Ox-Bow Incident is about how so much of what claims to be justice is just revenge in pretty clothes, about how our prejudices and preconceptions and assumptions are so easy to take as fact, about the near-irresistible pull of a mob. It could easily be an overly neat little liberal message picture, but it’s bloodied and bruising, so taut with tension that you couldn’t stand it if it was much longer. It’s a film about a lynching, but more importantly, it’s a film about a thousand moments where the townspeople could have chosen differently, each one of them a ton weight on the conscience. Human violence is not inevitable; it’s a choice. That isn’t any less true in places where life is cheap.

Because preconceptions of the Western are so ingrained across culture, people feel free to speak authoritatively without much first-hand knowledge. Mark Kermode is one of my favorite film critics, and I was confused and taken aback when he described The Dead Don’t Hurt (2023) as not a Western, but a drama that happened to have a Western setting, because it’s not full of “whole gangs of people on horsebacks, you know, rounding up the wagons”—an objection that would cast the vast majority of Westerns ever made out of the genre. I love the guys at Red Letter Media, and am still confused how they could think a film they watched cheaped out by having its final shootout in Monument Valley—John Ford’s preferred shooting location—instead of a frontier town set. (Mike Stolkasa only recognized Monument Valley from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and Jay Bauman and Rich Evans didn’t recognize it at all.) Everyone assumes they know what Westerns are like. But that knowledge is the result of a cultural game of telephone, unrecognizable from where it started. Everyone assumes they don’t need to bother watching Westerns, but every time I watch a Western—any Western, not even a particularly good one—it feels like cinema as a whole cracks open anew.

.png?width=352&name=r-cohen%20(1).png)