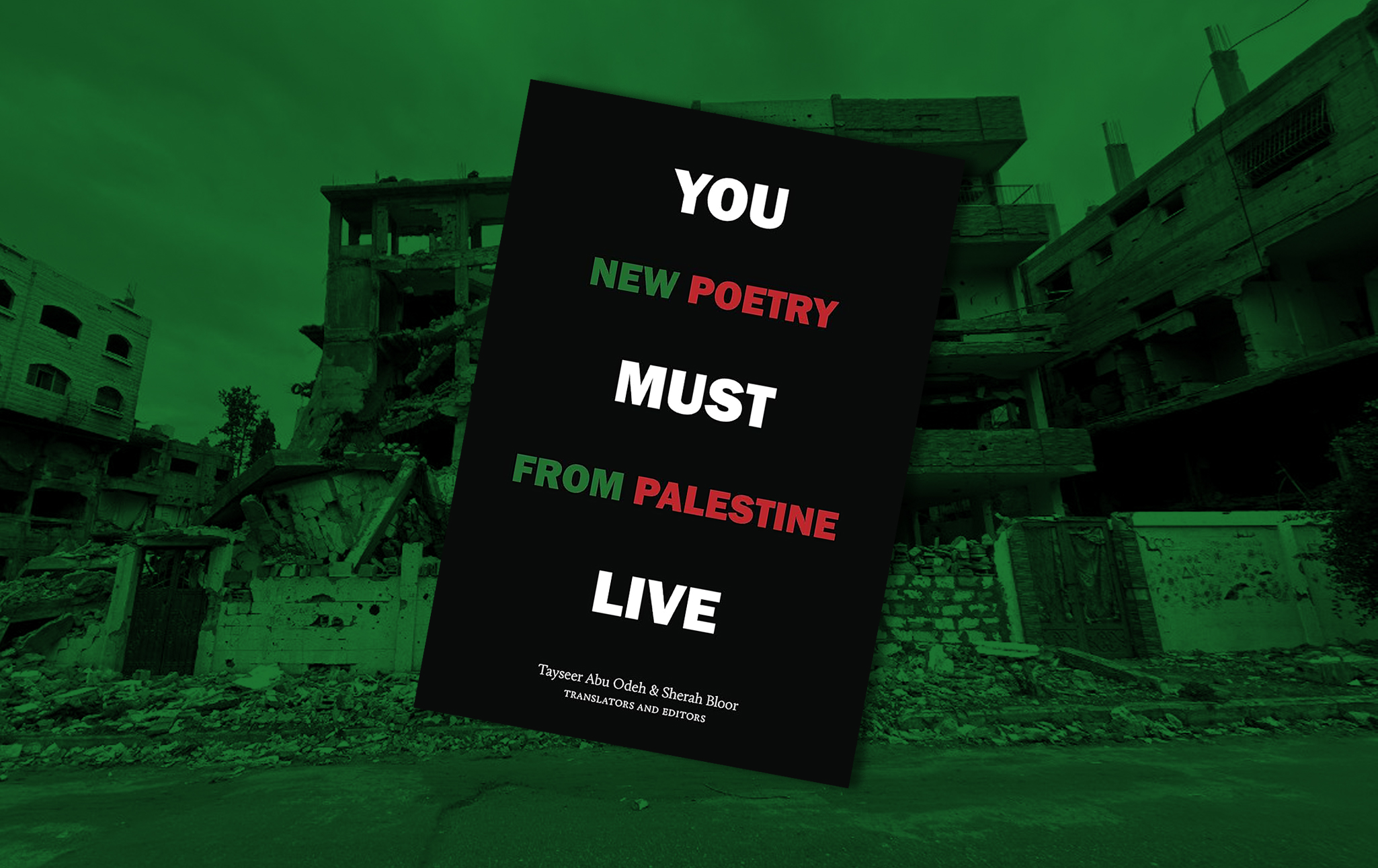

Inspired by the late Dr. Refaat Alareer, 34 Palestinian poets have captured the tragedy, humanity, and even humor of their homeland during Israel’s genocide.

Because poetry by Palestinians of the diaspora is more readily available to English-speaking audiences—for example Out of Gaza: New Palestinian Poetry, published by Smokestack Books, 2024—the editors, with the exceptions noted above, chose to feature primarily poems by writers still in Palestine. Of the poets in You Must Live, only Mosab Abu Toha (Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear, City Lights, 2022; Forest of Noise, Knopf, 2024), and Nasser Rabah (Gaza: The Poem Said Its Piece, City Lights, 2025) have published collections available in English.

Translation is always a dicey undertaking, and translating poetry is even more fraught with pitfalls and potholes. What works poetically in one language may not work in another, and vice versa. As the editors themselves acknowledge, “Often translators must betray the letter of a poem in fidelity to its spirit, in a careful balancing act. In this sense, the original and its translation are inescapably two different poems.”

To compound this difficulty, you should know up front that I have absolutely no knowledge of the Arabic language, or Arabic poetry, prosody, or traditions. While this anthology is bi-lingual, providing the original Arabic along with the English translation, that is of no value to me (though of course, it surely must be for anyone who is actually bi-lingual in English and Arabic). I must take it on faith that these translations are reasonably accurate and faithful to the originals, if not in form, at least in meaning.

That we have these poems at all is a testament to the tenacity of the editors and the courage of the poets. “Simply getting their poems to us was dangerous,” Odeh and Bloor write in their introduction. “Poems arrived as text messages, screenshots, photographs of handwritten pages, and as social media posts[...] every time someone’s phone connected to a satellite, or received a message, they became a potential target. And to reply might entail life-or-death decisions.”

This book has emerged from the midst of what can only be called a genocidal assault on the people of Palestine. What else can it be called, with at least 70,000 dead so far and perhaps as many as 10,000 bodies still buried under the rubble, infrastructure destroyed, water and sewage facilities destroyed, hospitals and clinics destroyed, apartments and homes and businesses destroyed, schools at every level destroyed, food aid denied, a “ceasefire” during which, according to Al Jazeera, 586 Palestinians have been killed and another 1,558 injured, pogroms in the West Bank perpetrated by Israeli “settlers,” while Donald Trump’s lapdog son-in-law Jared Kushner touts a plan to displace the Palestinians still alive and replace them with luxury high-rise beachfront developments for a Gaza Riviera?

In the midst of all this, that poets are still writing, still creating art, still refusing to be silenced, is nothing short of astounding. But they are. “Writing, for me, is like breathing—an action of life and survival,” says Waleed al-Aqqad. “I must write to immortalize the horror of Palestinian suffering and to resist oblivion.”

Hind Joudeh, who describes Gaza as “the largest open-air prison in the world,” adds that “writing remains the radiant fruit of my heart[...] my craft is a means of self-definition and understanding, reflecting the resilience and heartbreak of my people. Developed amid multiple wars on Gaza, my writing explores the tension between war’s omnipresence and the yearning and continuous struggle for the semblance of an ordinary life.”

For Nasser Rabah, “writing has become an inescapable duty[...] writing is an art of survival. It is also a labor of love[...] a form of resistance, a way to deny our tormentors the satisfaction of triumph. So we keep writing. We owe it to history, to justice, and to the truth that does not perish.”

“Writing in the besieged city of Gaza is an aesthetic and existential ordeal. The rubble, the corpses,” says Yasir al-Waqqad. “The dying is ongoing and daily.” To which Maher al-Maqousi adds that it is impossible “for those living outside of Gaza to truly imagine our extreme and bewildering grief, this repression, injustice, and the death. And the death. And the death and the death and the death[...] This is one of our biggest catastrophes—other people see our deaths as routine.”

And yet these poets, over and over again, insist on making it possible for those of us “living outside of Gaza” to imagine their grief, the repression and injustice and death they are living with constantly, to be moved by it, to refuse to accept any of this as “routine.”

But what of the poetry itself? Death, of course, is everywhere. Waleed al-Aqqad writes in “I have never seen a corpse intact”:

We said goodbye

to you in your small death like the death

of sparrows.

Othman Hussein, addressing a hungry dog in “I’m fed up with death,” writes:

As to you, dear dog,

don’t maul my corpse.

***

I go hungry, like you, O loyal one,

and I don’t eat you.

***

So let my dead body decompose.

Do not approach it.

In “When the Soldiers Leave This Place,” Khaled Juma writes to his daughter:

And the mirror shattered by a rifle butt

is the mirror in which you checked your braids

while I waited,

impatient to take you to school.

And your fat kitten,

I mean, your dead kitten,

kicked by a soldier’s boot,

is the same kitten.

It is only, my beloved, that those soldiers were here.

Hashem Shalola writes in “Blood’s Tale Narrated by Its Audience”:

You attend the wedding of a dying truth.

But it turns into a bloodbath within two minutes.

The wedding guests all get murdered.

Perhaps the most heartbreaking poem in the entire collection—and that is saying something—is Ala’a al-Qatrawi’s “A Tent from the Sky,” addressed to her four children, all killed at the same time in an airstrike on her home. Each of the first five stanzas of this long poem begins with a question:

“What does my tent look like to you now from the sky?”

“What does your mother look like to you now from the sky and how do you see her longing?”

“What does Gaza’s sea look like when it craves a kiss and there’s no trace of lips.”

“What does Gaza look like to you now?”

“Did you open your windows in the sky to see your mother bleeding?”

But there are also beauty and grace and tenderness in these poems. Another poem of al-Aqqad’s, “You made a mistake. You abandoned us,” ends with this: “I asked you, where would you like to be buried. / And you said, smiling, ‘in your heart.’” Hamid Ashour writes in the prose poem “Displaced Dog . . . Homeless Human,” “He stayed with me from the beginning of the invasion. We shared fear, barking, shrapnel, and canned meat[…] We made a tent from old rags, reeds, and palm fronds. We shared it like friends. When one of us slept to dream of return, the other guarded the dream and the road.”

Kifah al-Ghusin remembers her childhood in “Take me to the city gates”:

We mixed our days with sugar,

Shared love candies, chitchatting into the night.

We stuffed time with dreams,

Stuffed ourselves so we could get through it.

We fancied long-stemmed roses bowed

At the door to waltz us into adulthood.

Looking toward the future instead of the past, Hala al-Shrouf writes in “We will meet, don’t be in such a rush”:

In twenty thousand years, when the dust settles on this earth

and the despair, and

its fires burn out, and it recovers from horrors that today seem endless,

and the planet returns to what it was twenty millennia ago—

green with blue water, and white clouds always—

then we will meet.

***

You will see me and fall into my arms.

I will see you and fall into your arms.

There is even humor to be found here, albeit a kind of black humor. In “The Story of My Old Shoes,” Yasir al-Waqqad writes that

I left my old shoes

with all our belongings

when the shelling

caught us off guard,

but came upon them again

at the shoe seller’s

in the Rafah refugee camp[.]

***

The salesman mumbles, “Eighty shekels,

Will you buy them?”

“Me? Buy them?

They are my shoes, you petty people.”

The pair’s known me forever.

And here is Khaled Juma’s “The Gravedigger” in its entirety:

I’ve worked in ten countries

as a gravedigger.

A little shovel hung off my belt.

I walked about with it. A medallion.

In nine of those countries, things were normal.

One dead a week

or two, no more.

I said, I’ll retire to a city by the sea.

And I came here, to Gaza.

Now my shovel is useless.

I bought a little digger,

then an excavator,

hired all the unemployed.

Still, it’s not enough.

I have built a business with death.

Now we are first on the stock exchange.

Second to none.

But humor, even black humor, can only be a fleeting escape from the reality of what Palestinians are living with and dealing with every minute of every day. Jabir Sha’ith writes in “When the Hearth Burns”:

The ash harms you.

Nobody knocks on your door.

Nobody shares the hearth. Nobody shares your stove-warmed tea.

And you say It’s fine, it’s fine, perhaps they’re busy.

Then the fire goes out.

Then the last logs are embers.

And you spend the night like a lone wolf.

And you know why nobody knocks.

Hind Joudeh’s poem “Drums” ends like this:

Your child still wants a backpack of books.

How much of him has fear devoured?

Does he mourn his murdered teacher?

War beats on its drum. It keeps on beating.

It tunes its deaf ear to the screaming of children.

Khaled Juma, author of “When the Soldiers Leave This Place,” and “The Gravedigger,” ends “When the War Is Over” with

I won’t search for my lover’s grave.

I won’t write poems about her.

I’ll pretend I left her. That I didn’t love her.

***

And when that curious man asks what is written on that grave,

I will say It is just a coincidence of name and age. Nothing more.

And I’ll leave before he asks

But then what are you doing here?

And here is another heartbreaker by Juma, who seems to be my favorite poet in the anthology, if “favorite” is even an appropriate word to use.

Just a Loaf

For ten or so days

I’ve been searching for a loaf,

just a loaf.

They said it vanished from global warehouses.

A child saw it take to the stage,

or was it bombed by a plane.

The loaf is elusive, and my feet are tired.

My little ones don’t understand,

they think they’re in the old days,

you ate whenever you got hungry,

they wonder what they did wrong,

why do I punish them with this hunger and this thirst.

The last thing my youngest says to me this morning—

isn’t this too much punishment, Dad?

You would have to have a heart of stone not to be moved to tears by such a question. Imagine your child asking you that? Imagine it! This is what these poets insist you imagine. This is what Palestinians are living with constantly, daily, and with no end in sight. This is what these poets need you to understand. This is not routine. This is not okay.

And the fact is that your tax dollars—and mine—have been paying for the bombs and bullets and artillery shells that have caused so much misery and death, not just since October 7, 2023, but for three quarters of a century. When will it stop? When will Americans begin to care enough about Palestinians to insist that the Israeli and American governments recognize the humanity of Palestinians and begin to treat them accordingly?

Suleiman al-Hazeen ends his poem “Just One Evening” with this plea:

We want just one evening

without rocket launchers,

without criminals, without planes,

without tanks,

without murderers.

We want just one evening.

Will such an evening ever come?

%20(1).png?width=352&name=Screenshot%202026-02-11%20at%207.02.58%20PM%20(1)%20(1).png)