Recently I discovered a piece of writing I don’t remember producing. I am still not ready to believe that it came from the future, because I am a sensible person and that is a ridiculous thing to believe. I just don’t know where it came from. Today, I found a second piece of writing. I cannot be sure whether I simply overlooked it the first time, or whether it has appeared since. It, too, appears to be written by me, yet the authors of the two documents cannot possibly be the same.

Sometimes I think about just how close we came to ruining everything. I don’t mean to become a “you kids don’t know how bad we had it” type, especially because I never had it bad myself, but I do believe it’s important to note just how far we’ve come and what it took to get there. It’s hard to believe today, but about thirty years ago people were literally asking whether human civilization should go extinct. Some talked about an impending apocalypse. There was a quite serious notion that we were heading for some kind of large-scale catastrophe, the rise of fascism or the total destruction of the planet. And the truth is, we were.

I don’t know how to get someone to understand, if they didn’t live through it, just how perilous that single moment truly was. The Trump era may seem comical to you, a bit of historical madness like the reign of Caligula, but for those of us who were young then and thinking about our futures, it was horrifying. The planet was heating, authoritarians were coming to power, and there were thousands of nuclear weapons poised to fire at any time. Day-to-day life had its charms, but there was a sense that the good things could not last, because things were beginning to spiral out of control.

What’s interesting to me now is not just how dangerous it was but how quickly we managed to reverse course. Historical change, it turns out, can be rapid in any direction. The Nazis can go from fringe clowns to terrifying rulers within a decade. But so, too, did we build something more beautiful than anything I could have envisioned when I was in my late 20s. Wandering through the world today, I cannot believe it is the same place I once knew. It seems so familiar, but it is so magnificent, so warm, so verdant and friendly. Sometimes people my age and older (I am 59) are asked what it was like to live through the development of the internet. The answer: I barely noticed. It wasn’t a change that mattered, compared to what happened after. I don’t think young people (oh no, I’m about to say I don’t think young people appreciate, what have I become?) appreciate the full extent of what has taken place. I used to worry, back when it seemed a real possibility, that when butterflies disappeared, after a few generations people would forget what they were even missing. Now the whole damn world is butterflies, and the problem is reversed.

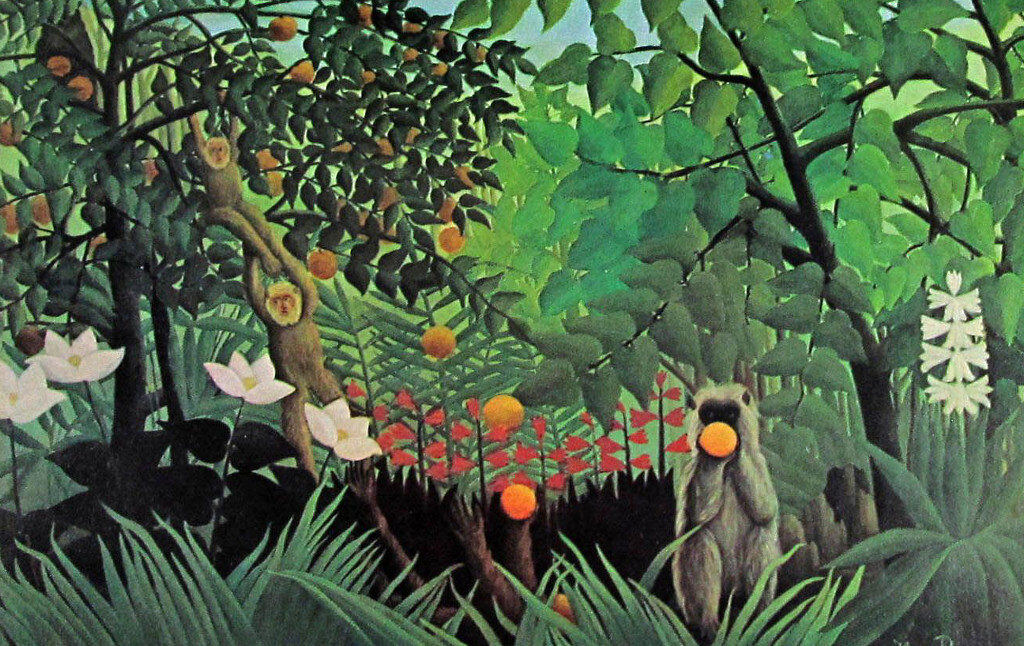

I don’t know if you’ve ever looked back at previous generations’ predictions of what the future would be like. They’re often richly amusing. But what’s striking about the time when I grew up is that people had almost stopped imagining. Our films and literature, when they imagined the future, could only turn dystopian. Yet even more creative generations could never have foreseen what actually transpired. Only Star Trek came close (and even they eventually gave up), but life today doesn’t feel like living on the Enterprise. For one thing, everything is so green, so teeming with life of all kinds. I think in order to understand the bleakness of 2019 you have to look at a photo like this:

What strikes us now about this picture is that it is so dead. Quite literally. Nothing in the picture, except a shadow of a person, is alive. It is like being on top of a mountain, or in space, but without the view. Imagine what it was like to see places like this everywhere, to have the whole world being turned into it. Today a photo like this makes us squirm—we recoil at the lack of warmth, decoration, beauty. The blankness of the walls, the utilitarian design. But this was an almost universal aesthetic. Whenever a new building was put up, it would almost always look like this. Is it any wonder that we felt “futureless”?

The rediscovery of life changed everything, and I mean everything. In the early part of this century, before 2020, “environmentalism” had a kind of fringe vibe to it. To be “green” was to have a pet cause, and I literally remember thinking that I hated the color green and I wished the “hippie-ish” associations of environmentalism would go away. I associated it with “urban gardens” with people toiling in dirt to raise a small handful of tomatoes. I’m ashamed that I never saw that with a simple adjustment, it could turn from something pitifully marginal to something all-encompassing and powerful. We did not need “urban gardens.” We needed The Urban Garden, a city of flowers. I think it’s just that phrases like “harmony with nature” had become cliches, their associations had dried up. Do you know that they didn’t even teach plant identification in schools? The miracle of life had ceased to be miraculous. “Nature” was seen as distinct from civilization. Even conservationists reinforced this totally erroneous framework: they wanted to “conserve” the natural world from the encroachment of humanity. You can see why we were heading towards planetary destruction! If you look at the “environment” as something separate from “us,” it will not seem necessary to cultivate or care about it.

The most striking changes in my lifetime have been in the way people think about things. Animals, as you know, were still eaten, with everyone just uncomfortably pretending that the moral problem didn’t exist. The presence of wild animals in day-to-day life today is still striking to me. In the old “gated communities” every trace of wilderness was violently extinguished. Now the presence of animal life is seen as the mark of a place’s vitality. (Today I had to shoo a toucan from my windowsill.) If you wanted to go from one country to another, you had to bring a “passport,” an absurdly elaborate identification document issued by a bureaucratic agency, and the “borders” between countries were militarized and patrolled. How refreshing it is today to look at a map and see countries defined as general areas rather than fixed territories. (One of the most bizarre things in old newspapers is seeing countries referred to as if they were people—“China Goes To The Moon” and the like. Seeing countries as individuals made it easier for us to see ourselves as being in competition with them. Is China gaining on “us”? When of course, we are all one big “us.”) I suppose I should mention the prison system, another feature of life that was taken as a given. Or the gap in wealth between black people and white people. Endless justifications for these things were put forward. You wouldn’t believe how cruel and indifferent to the fate of others some people could be.

There are countless aspects of everyday existence that were almost unthinkable then. Today, when you visit a branch of the GHS, you barely think about it. You find the nearest clinic in whatever country to happen to be in, make an appointment, go, and leave. That is not how it used to go. The idea of a “Global Health Service” would have seemed insane. For one thing, the idea of “world government” and even the word “global” itself had negative connotations. Today we might rejoice in our interconnectedness, but when our governments were dysfunctional, it was very easy to argue that more “government” would be doubly dysfunctional. So healthcare was a patchwork, and it was expensive. You literally had people begging not to be put in an ambulance because they knew they’d receive a huge bill afterwards! You had to find a doctor who would “take your insurance” (healthcare was covered through insurance plans) and even then it could be unaffordable. I remember that when I was in my late 20s, people had to do “crowd funding” campaigns to raise money for their medication. Sometimes they didn’t raise enough money, in which case they might die.

Part of me wishes everyone could relive that era for a day, so they’d know why what we have is special. When I stroll through the city to work, across rope bridges, through gardens, sometimes I find myself near tears. “Who are we that we can be so cruel?” I used to ask. Today, it’s “Who are we that we could build something so incredible?” Perhaps it’s not surprising at all. We were gifted a paradise, and all we needed to do was learn to love it, to manage it correctly and not kill each other. Should have been easy. But it wasn’t.

That’s something I really want to emphasize, not because I think we’ll ever find ourselves in the same position again, but because the people who made the changes happen deserve to have the scale of their achievement recognized. As I say, we were on a path to destruction. It took an immense burst of collective action to steer us away. If you asked me what the “key moment” was, I think it was probably when the Democratic Socialists of America resolved that every single member of the U.S. Congress would be a socialist within twelve years. Every single Congressional and state legislative district, without exception, had a young socialist running in the Democratic primaries. They were organized, and they began to win. The Sanders presidency, like Corbyn’s tenure as prime minister, accelerated the transition into overdrive. A few small victories that began to meaningfully impact people’s lives (such as the Jubilee), then a consensus was built around democratic socialism, from which there was no going back. The adoption of that principle was key, though: Never have an election, at any level, without a socialist candidate running.

It wasn’t just electoral, of course. The organization of workplaces and the development of the One Big Union helped tip the balance of power away from bosses and owners. Internationalism was critical—when the Democratic Socialists of America became the Democratic Socialists of the World, they were finally able to build the worldwide solidarity that was necessary to stop the infamous competitive “race to the bottom” among countries. The ethic of solidarity: it blossomed everywhere. God, it was a time. It felt like being shaken out of a stupor. Of course, the hard work was in actually figuring out the solutions. They took power easily, but avoiding disastrous experiments in social engineering required a commitment to “pragmatic radicalism,” a willingness to think hard about questions like “How do you stop capital flight?” (Capitalism encouraged sociopathy, actually necessitated it in many cases, and capitalists would rather destroy a country and countless lives than see a small bit of their power eroded.)

It was hard and it was easy. It was hard in that it demanded a hell of a lot of hard work from people. It was easy in that once we “got the ball rolling,” the changes happened rapidly. Once you improve something, it’s hard to undo it, so once it was understood that a workplace needed to be democratic, democratic it was forever. Once the “green quotient” became law, it wasn’t going to be undone. Colleges knew there would be an outcry if they reimposed tuition fees, nobody was going to build another slaughterhouse once meat became both unnecessary and inefficient. You couldn’t build a wall between countries if you didn’t know where one ended and the next began, couldn’t build a prison if you didn’t have crimes. I am not saying the world today is perfect (I just had an argument with my neighbor about religion’s place in political life.) We have not reached “the end of history,” a silly notion. But of course there is a sense of excitement about where we are going next. We can approach the “Final Frontier” safe in the knowledge that when we encounter the beings of other planets, we will do so as comrades rather than conquerors (God forbid they are in the same vicious, self-destructive stage we ourselves were so recently).

I am starting to get a bit old, not that age means much now. (My doctor tells me that I could live for another 500 years, hopefully enough time to become good at drawing animals.) I am aware that by spending too much time talking about my memories, I may sound like a long-winded fogey. But I can’t help obsessing over that historic turning point in 2020, that incredible moment when everything suddenly began to feel different in the most wonderful way. The buildings became beautiful again, so much so they took your breath away. (I wouldn’t even quite know how to describe today’s buildings to a stranger. They look more like plants than human-made structures, as if Gaudi was commissioned to do a Garden of Eden.) The trees and animals were everywhere, like living in an Henri Rousseau painting. (Though personally I still prefer the library to a hiking trail!) The workweek was shortened, the militaries all disbanded. Guns became the curious artifact of a dysfunctional past. People wear costumes whenever they please, they have luxury without materialism. Mardi Gras used to only be celebrated in New Orleans, but look at it now! There are no more “museums,” just as there is no more “conservation,” because art and nature are everywhere rather than confined. Every school is gorgeous, with students learning everything from literature to animal husbandry. I am not telling you anything you don’t already know. But I swear to God the orange juice even tastes better!

Today, I look back on all of this and think: how differently it could have gone, and how fortunate we are that it didn’t. Or perhaps “fortune” had nothing to do with it. The people of that time had a choice, and we can all be grateful that they chose so well, did so much, bequeathed us the marvel that is today’s Earth.