Why Millennials Are The Way They Are

Are young people totally dysfunctional, and if so, is it their fault?

Criticisms of millennials are notoriously broad in their scope. We have ruined everything, from golf to soap to the diamond industry. We’re shitty novelists. We give babies weird names. We don’t like boobs enough. We’re bad with money and don’t use napkins. We’ve already killed lunch and the Olympics, we’re in the process of killing Buffalo Wild Wings, oil production, and beer companies. We have never seen a cow. We love Christmas music. We made sex worse. We got Trump elected. We’re lazy, spoiled, tech-addicted. And we’re never going to make anything of ourselves until we quit frittering away our savings on sandwiches and avocados and develop a serious work ethic. (I am grateful to Luke Savage for compiling these into a list, albeit only a partial one.)

In Kids These Days: Human Capital and The Making of Millennials, Malcolm Harris sets out the brief for the defense in response to these various charges. Many of the allegations he does not attempt to deny; he makes no effort to prove that millennials actually do like farming and breasts and soap. Instead he argues, roughly: if millennials are dysfunctional, it it is not because they have chosen to be, but because the generations above them have built a world in which dysfunction is inevitable. Nobody chooses the circumstances of their birth, and older people “changed the world in ways that have produced people like us.” We have been made by our circumstances, and our circumstances suck.

“How are millennials different?” is not the interesting question. The interesting question is “Why are millennials different?” What is actually changing for them that results in their becoming different kinds of people? First, plenty of the alleged differences are probably either perfectly rational or the kinds of natural changes in taste that occur over time. Baby names probably grew weirder because it’s fun to be creative and people didn’t want their children growing up constantly having to go “Wait, which Sarah?” like they did. Golf is boring and an environmental catastrophe. (Discovering that Barack Obama liked golf was the first moment I became truly suspicious of him.) Likewise, good riddance to Buffalo Wild Wings and fossil fuels. (I can’t defend our inexplicable love of Christmas music.)

The most important differences, however, are the changes in personhood that have been driven by changes in the economy. Harris argues that millennials have faced a uniquely unfair economy, one substantially different from those their parents experienced. If they’re “bad with money,” it’s mostly because they’re debt-ridden and stressed out, and because it’s impossible to be “good with money” if you don’t have any. If they’re addicted to social media, it’s because we live in a more atomized and lonely world that lacks community supports. And if they’re not having sex, it might be because they’ve been told that fun is an impermissible luxury, one nobody who wants to stay afloat has time to indulge in. (As Harris says, “It takes idle hands to get past first base, and today’s kids have a lot to do.”)

Here is the world that Millennials live in, as Harris depicts it: as inequality has increased, competition has become increasingly brutal. Capitalism encourages owners to constantly reduce labor costs; a great way to do well as a private equity firm is to buy a company, fire half the employees and tell the remaining half to work twice as hard, and then sell the company. Wages aren’t rising, but we’re working harder and producing more than before.

As the economy becomes more “dog eat dog,” it has affected how children are being raised. From a very young age, they are increasingly being prepped to compete in the job market. Harris quotes a letter from a school explaining why the annual kindergarten play was being canceled: the children simply couldn’t afford to waste two days practicing a play, since the school is “responsible for preparing children for college and career with valuable lifelong skills” and “what and how we teach is changing to meet the demands of a changing world.” Harris says that decisions over how children should spend their time are now made with an eye to cultivating their “human capital,” the knowledge, skills, and personality traits that will make them attractive to potential employers. One school brags of its “kindergarten-to-career” pipeline, and since all leisure time has an “opportunity cost,” children are given enormous piles of homework and deprived of recess. Some have called for an end to summer vacation, because during it students “lose ground” in the never-ending struggle to be college-ready. Everyone is involved in the “arms race that pits kids and their families against each other in an ever-escalating battle for a competitive edge.” And the more schoolwork is designed to give students the skills that employers happen to want rather than that cultivate a human to their full potential, the more education becomes a form of unpaid job training, i.e. child labor. Harris talks frequently about the concept of the “pedagogical mask”: how activities that are designed for the purpose of maximizing your economic potential are disguised as having educational benefits.

Because children are increasingly seen as “precious appreciating assets,” Harris says, parents are more paranoid about their safety. The philosophy of “harm prevention” has given way to a philosophy of “risk elimination”: instead of letting children be free, today’s children are coddled to the point where no risks whatsoever are acceptable. Harris discusses “helicopter parents” who obsessively monitor their children’s activities and schedule every minute of their days. This kind of intensive parenting is becoming standard, he says, with everything chaperoned and nothing left to chance. He cites a study on the lives of child violinists, who seem to live a miserable existence characterized by almost nothing except eating, academics, and violin practice.

We are, he says, demanding too much of kids. What was once “high achieving” is now “normal”: more AP classes are being taken than ever before, more time is being spent on schoolwork, and children are less free. They are also policed more: school suspensions have increased and zero tolerance policies have introduced harsh punishments for single slip-ups. This has had particularly brutal consequences for the students of color who suffer disproportionately, and who fall into the “school to prison pipeline.”

Universities, too, are increasingly adopting the “human capital” view of students, Harris says. Even public universities increasingly operate like businesses, and are bloated with administrators drawn from the private sector. Schools have hiked tuition through the roof, and paid for huge legacy construction projects instead of improving instructor compensation. The “adjunct-ification” of academia has meant that instructors are poorly paid and have little job security. Overall per-instructor payments and the share of budgets allocated to teaching have declined. Many universities seem to be portfolios of assets rather than educational institutions, with an “ever-expanding real estate holdings, hospitals, corporate partnerships, and sports teams that are professional in every sense of the word—except that the players work for free.” Harris spends a good deal of time exploring the scandal of unpaid student athletes, who make money for their institutions while reaping nothing in return (except, perhaps, CTE).

Universities are also the gatekeepers of social success: they conduct the “weighting and sorting of children according to their value” and determine whether young people will end up in comfortable professions. “College admissions are the ‘boss’ of aspirational achievement,” Harris says. The already-well-off are favored in this competition: they know which little dances to perform in order to impress administrators. Working-class students will probably have to hold jobs during college, and their grades will suffer. They may have to work late into the night: a quarter of students at Wisconsin public colleges worked jobs during hours between 10pm and 8am. But it requires more and more effort to get to the top of the pile: we’ve all heard about the process by which jobs that used to require a BA now require an MA, the MA jobs need PhDs, etc.

Then there’s the actual workplace. Harris discusses the exploitative hell of unpaid internships, uncompensated labor that one must perform in order to cultivate one’s human capital. He likens the process to Tom Sawyer convincing the other children to pay him for the privilege of whitewashing a fence: you are expected to be grateful for the privilege of doing grunt work. As with the skills-based teaching of high school and college, one is being paid for one’s efforts in “gold star” homework stickers. Worse, Harris says, lower-income students are actually more likely to take unpaid internships than higher-income students, meaning that the people who most need to be compensated are often the ones most deprived. (By the way, there is even such a thing as a barista internship.)

Capitalism’s relentless pressure toward getting more out of workers for less has made workplaces tougher. The proportion of people working 50 hour weeks has increased, and Americans are more sleep-deprived than ever before. And for millennials, that hasn’t translated into financial success: they aren’t accumulating wealth, they’re much less likely to out-earn their parents than previous generations, and they have, as we know, piles of student debt. (Though, interestingly enough, they tend to have less credit card debt, though that might just be because we’re too stupid to understand how credit cards work.)

Because we’re trapped in debt, with stagnant wages, constant competition, endless pressure toward amassing additional credentials, millennials are psychologically unhealthy. There have been major increases in depression among teenagers, and young people are more anxious and mistrustful. They have “greater levels of restlessness, dissatisfaction, and instability.” Harris says we are “wagering a generation’s psychological health,” and failing to appreciate the effect of the economic system in producing anxiety and unhappiness among young people.

As Harris summarizes his conclusion:

“Increase in average worker output, rationalization, downward pressure on the cost of labor, mass incarceration, and elevated competition have shaped a generation of jittery kids teetering on the edge between outstanding achievement and spectacular collapse.”

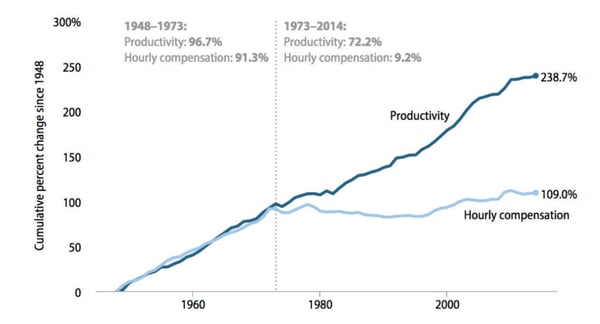

One of the most important points he dwells on is that, contrary to stereotypes about their indolence and distractedness, younger people are actually very productive. But they don’t actually reap rewards in proportion to that increased productivity. He displays the infamous chart showing the divergence between productivity growth and wages:

The markets are doing well, the economy is growing, and corporations are making healthy profits. That means, Harris says, that “the American dream isn’t fading, it’s being hoarded.” Rental income is going up; “generation rent” funnels much of its wages straight into its landlords’ bank accounts. “Postcrisis America has been a great place to own things and a really bad place not to,” Harris says. Meanwhile the portion of government spending going to young people (e.g. TANF) has decreased relative to the portion going to older people (e.g. Social Security), even as Baby Boomers have seen their wealth explode compared to millennials. Harris says it would not be an exaggeration to say that “an anomalously rich cohort of elderly people has been starving poor children of tax dollars.”

The big paradox of millennials is that we are incredibly well-educated and incredibly productive, and yet worse off than previous generations. Harris says this is because of capitalism, and explains what he means through an amusing parallel from the 1958 children’s book Danny Dunn and the Homework Machine. Danny is a whiz-kid who wants more time to play after school. So he builds a computer that can do his homework for him. Sure enough, his free time increases. But Danny’s teacher is clever: as Danny’s capacity for doing more homework more quickly grows, she simply adds additional assignments to his workload. Soon, he is spending more time trying to get the computer to process greater amounts of homework than he ever spent on homework to begin with.

That’s capitalism, Harris tells us. If a worker at the widget factory figures out how to make twice as many widgets in half the time, we could make the same number of widgets per day and go home earlier. Or, we could increase output without reducing the workday at all. Since there is no workplace democracy, and nobody gets to vote on what to do except the owners of capital, automation and innovation do not end up making life easier. Workers don’t see the benefits of increased productivity.

Another important point: the ceaseless competitive drive also makes us more productive, but that’s not necessarily a good thing. If you can’t get a job without a PhD, more people will get PhDs, and they’ll learn a hell of a lot of information. But it’s not clear that it’s actually necessary and it might make them very unhappy. If there can be only one superstar violinist, and the person who practices the most wins, there are going to be a lot of very well-trained violinists. They might also all have depression. While defenders of the Great American Free Market Way Of Life are not wrong that competition unleashes a phenomenal amount of human potential, it’s worth remembering how perverse this can be. After all, if I kidnap six people, and I put them in an enormous sandbox, and I say that whoever builds the largest sandcastle in 20 minutes will live, while the others will die, it is likely that I will soon see some very large sandcastles. But I am also making their lives hell. Increases in productivity can’t be the only measure of success, because they can mask widespread human misery.

Kids These Days usefully documents the economic forces shaping millennial life. It’s also a nifty bit of applied Marxist analysis that (thankfully) doesn’t mention Marx once: it shows, in simple and friendly language, what it means to say that society and culture are shaped by historical and “material” factors. And it forces us to confront the paradoxical and incoherent stories told about millennials:

“On the one hand, it’s generally acknowledged that students are doing historically anomalous amounts of homework and that competition for desirable college slots is stiffer. On the other, these same kids are depicted as slackers who are unable to sustain focused attention, entitled brats who need to be congratulated for their every routine accomplishment, and devolved cretins who can’t form a full sentence without lapsing into textspeak.”

There are a couple of weaknesses with Harris’ book. First, the whole narrative is oversimplified. I have just relayed the story as Harris tells it. But as you can see, it’s not exactly nuanced. Just like Marx, it finds a causal factor and then makes that factor all-determining and all-consuming: the relentless corporate drive for profit is warping and destroying millennial life. Harris says that “the Millennial character is the result of a life spent investing in your own potential and being managed like a risk.” But we can all see the problem here: the “millennial character” is a generalization, and Harris often treats things that are “increasingly true” as being “universally true.” I’m not sure that they all are, though.

It’s certainly the case that among urban elites, there is strong pressure for children to attend a prestigious college, which can result in a hypercompetitive environment in which kids constantly pursue “gold stars.” That’s a particular part of the world, though, not the entirety of it. I would bet anything that Harris himself is a child of the professional class, and that he therefore takes the tendencies he has encountered as being more ubiquitous than they necessarily are. (Update: this supposition turns out to be correct.) I’m younger than Harris, and my childhood just wasn’t like this at all. Neither of my parents had college degrees, and there was never any real pressure to think about getting into a good university, even though I went to a public school where nearly all graduates ended up at four-year institutions afterward. I can’t even really remember college being something I thought about much until before I applied. Social tendencies are not iron laws.

That may be changing, of course. Harris points out the ways in which education is becoming more standardized for everyone, with initiatives such as the Obama administration’s disturbing “Race To The Top” program, which pitted states against each other in a battle for funding, with monetary rewards for compliance with federal criteria. It’s obviously true, as Harris says, that companies want to outsource training to schools so they don’t have to pay for it themselves, and that euphemistic concepts like “preparing students for the challenges of a new economy” are ways of treating an unfair system as natural and inevitable, and forcing students to change themselves accordingly. But some phenomena he describes, such as the way wealthy New York City parents treat “playdates” as inter-child networking opportunities, remain (thank goodness) confined to the more nauseating social substrata.

Nobody should doubt the core point of the book: for many, many young people, the economy has become brutally unfair. I share Harris’ anger at those who have built a system in which people who work incredibly hard can barely even subsist. One of my smartest friends works at a movie theater where an hour’s wage can’t buy her one of the larger-sized bags of popcorn. Another friend who works in retail spent nearly a year trying to pay off a minuscule payday loan. I see brilliant people having to work numbing and stressful jobs, with zero say in how their workplaces operate, subjected to the constantly shifting expectations of dim-witted and cruel managers. To the extent that Kids These Days is reacting to criticisms of millennials by saying “Excuse me? You have the gall to blame us for this? Fuck you!” it is dead-on and extremely satisfying. It’s also a comforting book, because it correctly tells young people that, contrary to what they’re hearing constantly, what they’re going through is not actually their fault. With so many of them depressed, tired, and hopeless, that’s a vital message.

But this need for hope is also why the book’s final chapter—on solutions—is deeply, deeply infuriating. First, Harris tells us what he thinks the future holds: even more debt, the further professionalization of childhood, class disparities in how badly people are affected by climate change, constant surveillance, backlash by male misogynists to their declining social status, increasing mental illness, and the quantification of all things. Then he tells us why all the ways we might try to stop it will fail. If you think you can fix corporations by consuming products more ethically, you are wrong. (“There are many different flavors of Pop-Tarts, but none of them opens a portal to a world where you don’t have to trade half your waking life to get enough to eat.”) If you think volunteering for nonprofits can help, you are wrong: they are part of the problem. If you think protesting can help, you are wrong: as soon as your protest stands a chance of succeeding, the police will swoop in and destroy it. And if you think participating in politics will help, you are the most naive of all: “Political reforms seem beside the point if the next generation’s hearts and minds are already bought and sold.” Even if, for example, you could tighten rules on unpaid internships, “there would remain young people willing and eager to break the rules in order to sell themselves short.” Besides, “the young people who could provide the type of leadership we need—kind, principled, thoughtful, generous, radical, visionary, inspiring—won’t touch electoral politics with a ten-foot pole,” and rebuilding the political system would take “more time—and probably a different country—than we have.” All he says about what we can do is that we will either become “fascists” or “revolutionaries.”

This seems to me to be facile and irresponsible. You can critique the efficacy of “ethical consumption” without lapsing into total cynicism. And it’s simply false that kind and principled people “won’t touch electoral politics”: look at all the millennials who got involved with the Sanders campaign. Look at the socialists who are trying to win local political office. It’s actually a very encouraging time to be on the left, and those who pour cold water on people’s hard work, because they’re not “revolutionary” enough, are not helpful and should not be listened to. Pessimism is suicide. You have to believe that a better world is possible. If I were trying to help a confused teenager understand their world by giving them a copy of this book, I’d probably rip out the last few pages so that I didn’t make them even more depressed.

Still, this is the sort of book that is worth setting up a discussion group about. There are lots of questions in here that would be worth fleshing out with other people, e.g. How much are individuals shaped by their economic circumstances? To what extent should education be job training? How can competition be kept from spiraling out of control? What would a fair economy look like? Kids These Days doesn’t go into much depth on any single question, but it certainly provides a place to start. Just don’t listen when it says we’re all doomed.

Current Affairs is funded entirely by subscriptions and donations, and we depend on your support. If you want to help us continue our work, please consider purchasing a subscription or making a contribution.