This is Why You Don’t Let Libertarians Run Your Country

In Argentina, President Javier Milei has screwed the economy up so badly he needs a $20 billion bailout. That’s because his “free market” economics don’t actually work.

Of course Javier Milei has plunged Argentina’s economy directly into the toilet. Inevitably so. The news only broke last month that Milei’s government is in such deep trouble that it needs a $20 billion bailout from the United States to stay above water, which Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent is reportedly prepared to grant. But this outcome was practically foreordained, from the moment Milei became president back in 2023. You could tell he was going to crash and burn, and take thousands of Argentinians’ jobs and livelihoods with him, as soon as he uttered the word “libertarian.”

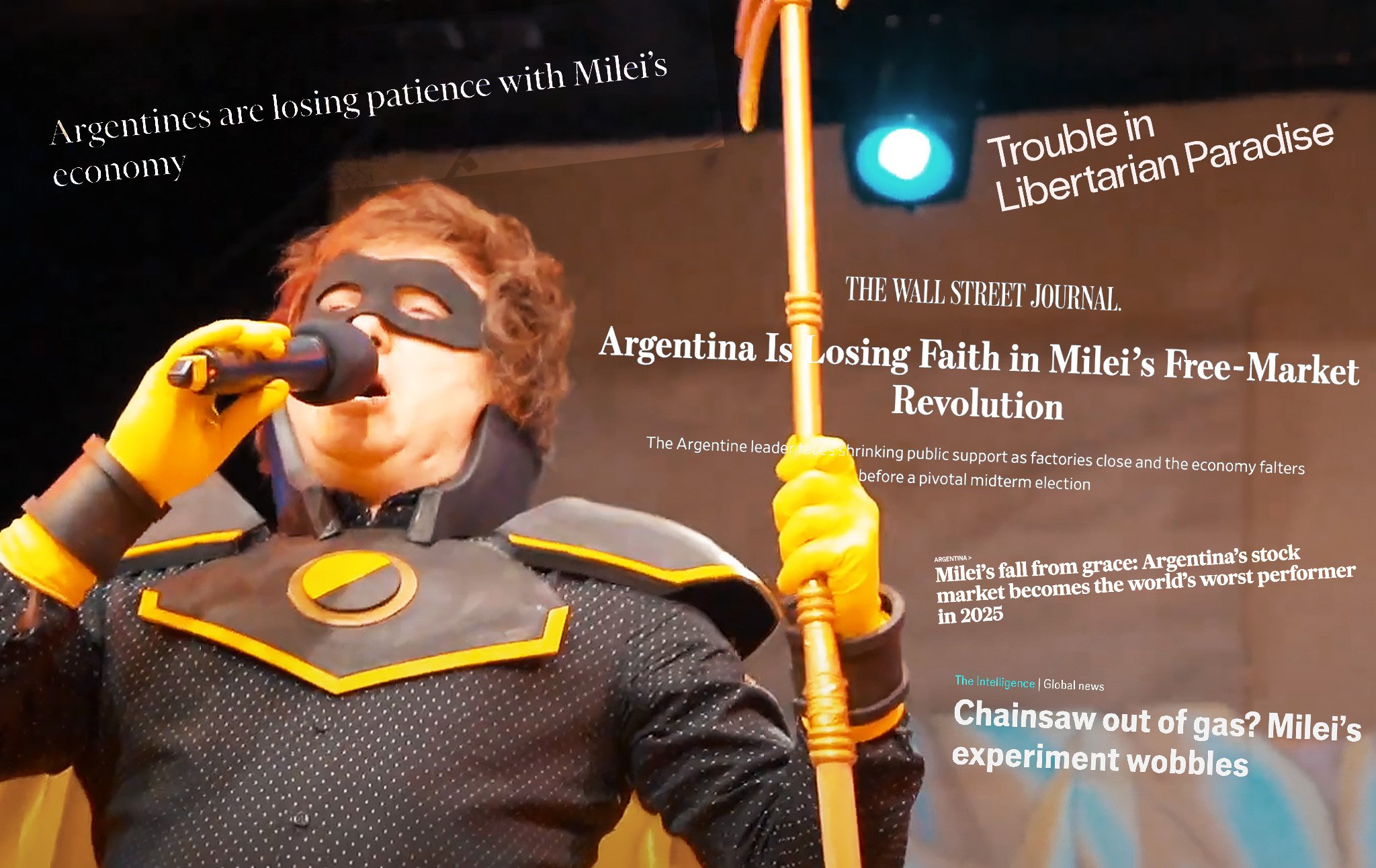

Even more so than Donald Trump to his north, Milei was the kind of erratic crackpot you can see coming a mile off. This was a man who dressed up in a superhero suit to sing sad ballads about fiscal policy, “floated legalizing the sale of human organs” on the campaign trail, and told reporters he takes telepathic advice from his dogs, who are clones of his previous dog. You didn’t need any special insight to know he wasn’t leadership material. But even those personal foibles would be inoffensive, even charming, if Milei had a sound economic agenda. More than the psychic dogs or the yellow cape, the really unhinged thing about him was that he took libertarianism seriously, aiming to slash the functions of the Argentinian state wherever he could. Now, Milei is facing a spiraling series of crises, from unemployment to homelessness to the basic ability to manufacture anything. He should serve as a big, red alarm bell for people far beyond Argentina’s shores—because right-wing leaders in the U.S. and Britain are explicitly modeling their economics on his, and if they’re not stopped, they’ll lead us to the same disastrous end point.

Until recently, a lot of prominent voices were loudly proclaiming the exact opposite. In fact, Milei’s presidency got a wave of media praise that bordered on the sycophantic. The word “miracle” came up a lot, like when the National Review informed us that “The ‘Milei Miracle’ is a Vindication of Free Markets,” or when historian Niall Ferguson wrote that “Milei is delivering a man-made miracle that should gladden the heart of every classical economist.” The Cato Institute claimed that Milei was an object lesson in “the Legitimacy of Libertarian Policy.” Over in Britain, the Telegraph gloated that “Milei beat his detractors and it’s delicious to watch,” adding that “the Argentine leader has proven he knows more than his Lefty critics.” Reason magazine went so far as to publish a “Libertarian Travel Guide to Javier Milei’s Argentina,” urging people to go see the “beacon of liberty” Buenos Aires had become firsthand. And Milei himself was loud and bombastic about all this, telling the World Economic Forum that he’d proven “free enterprise capitalism is[...] the only possible system to end world poverty.”

But pride goeth before the fall, and Milei’s cheerleading squad has fallen a little silent recently. It’s now been nearly two years since he took power, and the longer things drag on, the worse the economic situation looks. The Wall Street Journal sums it up like this:

Milei had predicted a V-like recovery with the creation of new jobs in a more prosperous and stable economy.

Instead, the economy stalled out, declining in the second quarter compared with the previous three months. Unemployment is at 7.6%, up from 5.7% when Milei took office. And Argentina has about 200,000 fewer jobs since he took office, government data shows.

Within that broader employment slump, the Buenos Aires Times reports that certain sectors show “significant decline,” with manufacturing having “4,162 less jobs in March while there were 2,088 less workers in agriculture, livestock, hunting and forestry and 1,185 less in education.” (Good thing keeping people fed and educated isn’t important, huh?) The value of the Argentinian peso has become unstable, sometimes becoming the “worst performing major currency” in the world on a given day. The housing market is similarly volatile, to the extent that banks are withdrawing loan offers as mortgage rates spike unexpectedly, leaving people who’d counted on buying a home unable to afford it after all. In a survey of people sleeping on the street in Buenos Aires last month, a local NGO found that an astonishing 25 percent of them had only become homeless in the past year, deep into Milei’s tenure. Meanwhile, literal breadlines are forming in the street:

At a nearby bakery in La Matanza, about 300 people line up every day for bread. Celia Cisneros, the baker, said many families don’t have the 75 cents for a bag of bread that is already subsidized by a local nonprofit. Others tell her the bread is likely the only thing they will eat that day.

For working-class people in Argentina, Milei’s presidency has been less a “miracle,” and more a curse. The U.S. bailout is just the latest indignity, and the news that the country’s economic future now depends on the whims of Donald Trump can’t possibly be improving anyone’s confidence.

Art by Jesse Rubenfeld from Current Affairs Magazine, Issue 49, July-August 2024. Writing by Stephen Prager.

Two questions need to be addressed here. First, how has Milei managed to screw things up so badly? And second, why did so many prominent columnists, authors, and think-tank denizens fail to see it coming? In both cases, the answer is the same: free-market ideology. Milei has dashed his ship of state against the rocks, quite simply, because he followed the cracked compass called libertarianism. Libertarianism doesn’t work. Its core assumptions aren’t true. It’s the intellectual equivalent of huffing paint. But the pro-capitalist press outside Argentina, for their part, ignored Milei’s obvious flaws and hyped him up because they wanted him to be the real deal. They’re still doing it. Just a few days ago, David Frum wrote in the Atlantic that Milei deserves to receive that $20 billion U.S. bailout so he can continue to “be the hope of everyone who believes in markets and democracy.” Call it “motivated reasoning” or the more modern term, “wishcasting,” but these commentators are indeed operating off “hope” and “belief” in markets, not solid fact. Now, we see the consequence.

One thing has to be acknowledged up front. The main reason it was relatively easy to sell the idea of Milei as an economic savior is because Argentina’s previous governments, the Peronist ones, left the country in a genuinely ruinous state. Peronism really only exists in Argentina, and there’s a good reason for that: it’s an incoherent mess, to the extent that it’s hard to tell what its tenets even are. Its creator, Juan Perón, said it was an ideology of the “left,” but explicitly “not a communist or anarchist left,” instead opting for a new philosophy of his own called “justicialism.” (One of the big Peronist slogans used to be “we are neither Yankees nor Marxists,” which leaves the obvious question “well, what are you then?”) “Justicialism” pulled elements from all over the place, mixing a little socialism here, a little Catholic theocracy there, and even some fascism. It’s scored a few notable gains over the years; Argentina has a universal healthcare system, for example. But mostly, it’s been an object lesson in the trouble you can get into by not having a consistent political theory, like Marxism or anarchism, to guide you. As the Economist puts it, Peronist governments tend to be “defined by power, not ideology,” with the main point being the strength of the current leader figure, and actual policy put together on an ad-hoc basis. In recent years, all of this resulted in a flailing Peronist administration that presided over a “hyperinflation” rate of 211 percent—and they didn’t do themselves any favors by running their economics minister, Sergio Massa, against Milei in 2023. Compared to that level of blundering, you can’t really blame Argentinian voters for taking a long shot on the weird libertarian.

But what, if anything, did Milei’s much-touted “miracle” actually consist of? Well, that’s where the problems start. When you look through all those glowing reviews of his performance, there are two points that keep recurring as his supposed “wins.” One was an increase in Argentina’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP): “The economy is now growing at an annual rate of 7 percent,” crowed Niall Ferguson. The other was bringing that super-high Peronist inflation under control. Now, both of those things are broadly true. But when you dig into what they mean, and examine the situation without an ideological filter that says markets and private property are always good, the perception of a “miracle” falls apart.

In the first place, GDP as a measure of “growth” is probably the most over-hyped metric in all of economics. Politicians around the world love to boast about GDP, treating it as an “all-encompassing unit” for overall prosperity. But as Amit Kapoor and Bibek Debroy point out at the Harvard Business Review, it isn’t one. In fact, simply having strong “growth” in GDP terms tells you almost nothing about how prosperous the actual people in a country are. Partly this is because GDP “fails to capture the distribution of income across society,” so you can have situations where a nation’s GDP is strong, but most of the income being generated is concentrated among a small elite, and the average citizen doesn’t see much benefit. (Hm, sounds familiar.) But more fundamentally, GDP doesn’t even show the production of goods and services as such, in objective physical terms. It doesn’t count how many potatoes have been harvested, or how many people are able to rent apartments. It only counts the market value of the transactions when goods and services change hands, which can be subjective and arbitrary. There’s a juvenile poop joke that illustrates this point well:

Two economists are walking in a forest when they come across a pile of shit.

The first economist says to the other “I’ll pay you $100 to eat that pile of shit.” The second economist takes the $100 and eats the pile of shit.

They continue walking until they come across a second pile of shit. The second economist turns to the first and says “I’ll pay you $100 to eat that pile of shit.” The first economist takes the $100 and eats a pile of shit.

Walking a little more, the first economist looks at the second and says, “You know, I gave you $100 to eat shit, then you gave me back the same $100 to eat shit. I can’t help but feel like we both just ate shit for nothing.”

“That’s not true,” responded the second economist. “We increased the GDP by $200!”

So praising Javier Milei because his economy had shown “growth” on paper, as Ferguson did, is largely pointless unless 1) that “growth” consisted of real physical objects and services, and 2) the proceeds were actually reaching ordinary people. It’s the kind of thing Joe Biden’s strongest soldiers kept doing online in the 2024 election, when they’d post graphs showing increased GDP and say that “the Biden economy is just booming, booming, booming,” even though in real terms homelessness was hitting record highs and people were defaulting on their credit cards in record numbers. It didn’t work for Joe, and it isn’t working for Javier.

Then, what about inflation? Nobody likes inflation. And yes, Milei has brought it under control in Argentina. But how has he done that? In his own puff piece on “Javier Milei’s early successes”—which, give him credit, was actually one of the more cautious and measured examples of the genre—Matt Yglesias euphemistically calls Milei’s strategy “spending cuts to control inflation.” The concept was that the Peronist governments had been printing money excessively to cover deficits, so government spending cuts would prevent that from happening, make the money supply more scarce, and gradually increase the buying power of the peso. All fairly standard liberal economics, as Yglesias points out, but cold comfort if you’re one of the government workers who got fired to make that increase possible, and thus have no pesos at all.

Now, it’s not that government spending cuts are inherently bad. Even Zohran Mamdani has recently pointed out that government efficiency can and should be a “left-wing concern,” and any leftist could name budget items for the chopping block—armored vehicles for small-town police departments, for instance. It’s also perfectly plausible that the Peronists had been spending money recklessly. But Milei’s cuts were not the kind of careful, well-thought-out ones that could actually be helpful, and they were not directed at government spending that was genuinely excessive or wasteful. Instead, as Nick Corbishley writes at Naked Capitalism, Milei “slashed spending on public goods like education, healthcare, transport and infrastructure,” even getting rid of palliative care at the national cancer institute. If he got a reduction in inflation, it’s not just because of the effect on the currency, but because he simply made a lot of people poor. As Corbishley puts it:

[T]he economic pain being visited upon millions of Argentinean workers and pensioners is not an unfortunate by-product or unintended consequence; it is the intended goal — to impoverish workers and pensioners to the point where they cannot fill their shopping basket or buy even the most basic of necessities. If you starve the economy of demand, inflation eventually has to go down. Which it has, albeit at the cost of almost killing the host.

Meanwhile, Milei did not cut purchases of “second-hand F-16 fighter jets from the US, via Denmark” (price tag: $300 million), and he lavished funds on “the ever-larger riot police operations needed to violently suppress public protests.” He also started a “$1 million initiative to improve diplomatic relations between Israel and several Latin American countries” as the Gaza genocide strains those relations to the breaking point.

These priorities reflect the usual right-wing worldview: feeding, healing, and teaching people is not important, but hurting and controlling them is. Defunding cancer treatments is obviously ghoulish, but slashing education for a short-term economic gain is just as bad. It’s like eating your seed corn for next winter—where are Argentina’s future doctors and engineers, and all the “economic activity” they generate, supposed to come from? But Milei is deeply committed to this stuff. When he got elected, he openly declared he’d be conducting a “shock treatment” on the country, echoing the “shock therapy” that was applied to post-Soviet nations in the 1990s to convert them to a free-market system. (Which, by the way, also didn’t work out, leading to falling life expectancy as countries became capitalist and widespread nostalgia for communism across Eastern Europe.) In practice, he’s delivered all shock and no therapy.

Manufacturing, in particular, gives us a useful case study. Here, the Financial Times reports that a key goal for Milei at the start of 2025 was to “break open Argentina’s protectionist economy” through aggressive free-trade policy. A “blanket tax of 7.5 per cent on all imported goods” was eliminated, and stores were “beginning to stock their shelves with Tide laundry detergent and Ecuadorean tinned tuna.” This was framed as a good thing, and for people who just wanted cheap detergent now, it probably was. But fast-forward a few months, and we find that the knock-on effect was to damage Argentina’s manufacturing capacity, creating even more unemployment:

Many Argentines purchase cheaper imported goods on Temu and Shein, the popular online Chinese marketplace apps. But the labor-intensive industries that politicians covet here, such as construction and manufacturing, haven’t recovered. Gustavo Murgia [a worker interviewed by the Wall Street Journal] hasn’t found work since his factory layoff last year. “I should be working, but what can I do?” he said. “The country is going backward.”

Altogether, “Manufacturing activity was down 12.7 per cent in the first nine months of 2024 compared with the same period in 2023.” So in essence, Milei is speedrunning the North American experience of NAFTA and deindustrialization. He’s trading a short-term crack-rock hit of cheap goods for the long-term degradation of entire industries people rely on for their livelihoods. To take just one illustrative example, Cellulosa Argentina—a paper company that had been in business for over 100 years—declared bankruptcy early last month, citing “lack of demand and the threat of imports” as the reason. And the main beneficiary of all this free trade will be China, which—as usual—can just sit back and watch Argentina’s manufacturing base decline, while continuing to expand its own.

At the root of all this is the core assumption of libertarianism: that the state is fundamentally bad, and markets are fundamentally good. Milei believes this in a very literal, dogmatic sense. Time after time, he goes on tirades about it, telling interviewers from the Economist that “my contempt for the state is infinite.” The state is “a violent criminal organisation that lives from a coercive source of income called taxes,” he says. When Tucker Carlson asked him what advice he would give Donald Trump, Milei declared that “The state can give you nothing because it produces nothing.” But that isn’t true. Taxes, no matter how often the slogan is repeated, are not theft, in part because money and property themselves can’t exist without a functioning government, and because you get government services in exchange. The state is capable of causing harm, of course, and civil libertarians like Radley Balko, Elizabeth Nolan Brown, and Matthew Petti are some of the best critics of things like police brutality and government censorship. But assuming it was democratically elected, the state is not a “criminal organization,” and claiming it “produces nothing” is just laughable. The state produces all kinds of useful things, from roads and libraries to new scientific breakthroughs private companies are unwilling to invest in. Argentinians with cancer probably wish it was still producing their medicine.

This becomes especially clear in times of crisis. When he was faced with the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt solved it by giving people jobs building bridges, roads, dams, and public housing, along with guaranteed Social Security income, all courtesy of the state. Unlike Milei’s free-marketry, it actually worked, and as Allison Lirish Dean recently wrote for Current Affairs, we can trace a lot of America’s current problems to the abandonment of the state as a powerful tool for making people’s lives better. Even the Peronists, for all their faults, succeeded in getting universal healthcare set up. You’d think libertarians, who typically favor gun ownership, would grasp the concept that it’s not the tool itself, but how you use it that’s good or bad, but apparently not. And when you build your entire politics on a false assumption, well, it’s no surprise that you end up with bad results.

Even Milei’s corruption is perfectly consistent with his status as the arch-libertarian of the western world. And although the investigations are still ongoing, it seems there’s quite a lot of corruption. Most recently, there was a bribery scandal involving Milei’s sister Karina, who’s one of his closest advisors, and allegedly “accepted bribes of $500,000 and $800,000 in exchange for government pharmaceutical contracts.” But before that came the $LIBRA cryptocurrency scandal from February of this year, where Milei “directed followers to a site that purported to raise money for small businesses in Argentina using crypto,” causing them to sink huge amounts of money into $LIBRA and raise its value over $4 billion USD—only for it to abruptly collapse when its largest holders sold off their shares in a classic “rug pull” scam.

Really, “crypto scam” is a tautology, since there are precious few legitimate uses for the stuff beyond “rug pulls” and other forms of shady, unregulated speculation. But libertarians adore crypto, and under their bizarre principles, nothing illegitimate necessarily happened here. After all, nobody promised that the value of $LIBRA would increase, and everyone made a free-market decision to purchase it; buyer beware, right? And why shouldn’t a politician have the right to make deals on the crypto market if he wants? Are you some kind of crazy communist, saying we should take away his economic freedom?

You can find echoes of this thinking even among liberals, like when Nancy Pelosi defended members of the U.S. Congress who trade stock in the companies they regulate by saying simply that “We’re a free market economy. They should be able to participate in that.” It’s socialists who have a strong concept of why public corruption is bad: as Zohran Mamdani put it in a rebuke of his onetime rival Eric Adams, it “doesn’t just enrich politicians and their friends. It diverts public resources, undermines effective government, and erodes already fading confidence in[…] democracy.” But for a libertarian, government is evil, there’s no such thing as “public resources,” and even democracy is suspect if it threatens private property. It’s easy to betray the public trust when you don’t have a concept of the public good, or a duty to anything higher than money.

For a while, though, Milei was able to paper over the cracks in his ideology and economics. Like a lot of Latin American leaders, he resorted to selling off his country's natural resources, making highly favorable deals with British companies to extract Argentina’s lithium and even removing restrictions on foreign land ownership, allowing international companies to buy “areas with fresh water, lithium, and other minerals” outright. (The United States, predictably, is the main country interested in such deals, and owns “nearly 2.8 million hectares” of Argentina already.) As Ben Norton points out at Geopolitical Economy Report, Milei also went pleading to the International Monetary Fund for an “emergency loan” back in March (estimated to be in the $10-20 billion range), “deepening the debt trap” Argentina already has with the notorious institution. This, despite his earlier promising not to increase the national debt.

Now, Milei is accepting yet another foreign bailout directly from the Trump administration. There are allegations that this deal involves even more corruption, since it benefits one particular Trump-aligned billionaire who “has invested heavily in Argentina,” is a personal friend of the U.S. Treasury Secretary, and “purchased more Argentine bonds” just days before the bailout announcement. But in any case, it’s a funny kind of “free-market” politics that can only be kept solvent through non-market means, especially given the usual libertarian rhetoric about “personal responsibility” and the immorality of handouts.

In fact, virtually all of the trite, hackneyed lines that defenders of capitalism use to scold socialists apply better to Milei’s libertarianism. It might sound nice on paper, but it just can’t work in the real world. The problem is that you eventually run out of other people’s money. It causes breadlines. Even Milei’s most dogged advocates, like economist (and cinema creep) Tyler Cowen, are now trying to say that real libertarianism hasn’t been tried in Argentina. As for all the pundits who pushed the “miracle” line, they now sound like the editors of small Stalinist magazines boasting about grain harvests in 1935.

This would be bad enough if it was just Argentina’s problem. But Milei has been influential. His defunding spree was one of the main inspirations for Elon Musk’s disastrous DOGE initiative to gut the federal government, which saw Musk waving a chainsaw gifted to him by Milei onstage at CPAC. There’s also trouble brewing in the U.K., where Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch sees Milei as “the template” for good economics, while the Reform Party’s Nigel Farage admires his “Thatcherism on steroids.” Unfortunately for the rest of us, the “free market” people currently run the world. We’ve got to take their economic power away from them, before we all meet Argentina’s fate.

-jpeg.jpeg?width=2550&height=3225&name=Libertarian_Dog_Squad_%20(1)-jpeg.jpeg)