A Warning to Unwary Travelers: This article includes graphic descriptions of (fictional) murders, along with spoilers for all the films, shows, and books it discusses.

One of the most valuable and engaging things about horror fiction is the way it allegorizes and gives voice to our collective fears and anxieties. Look at the horror stories of a given historical moment, and you can see a metaphoric record of a society’s hidden fears, the ones that can’t be openly acknowledged. In Dracula, we see the dread engendered by a decaying British empire, fearful of the outsider immigrant who moves to London to buy up British property. More contemporary examples can be seen in some of the biggest horror franchises of the past two decades. The subprime mortgage crisis of 2008 was also the year that horror gave expression to our collective fears around property and home ownership with the release of the first in the Paranormal Activity franchise, which featured a young couple moving into their first home and finding it as a site of demonic possession. Another example: the violence and surveillance of the “War on Terror” found expression in the neo-noir of the Saw franchise, which emerged in 2004 with its obsessions with surveillance and torture as a punishment for perceived moral failing. What we fear, what we’re made to feel revulsion for, is not simply a natural or instinctive response. Rather, it is a political question, and our own feelings of fear and horror are in many ways reflective of a cultural politics that we normally take for granted.

One persistent and underappreciated part of American culture that is rife with grotesque violence and pain is one of capitalism’s greatest horrors: the industrial farming system. Every year, billions of thinking, feeling animals are killed in American slaughterhouses. Beneath their bland appearance, meat factories are institutions of death on a colossal scale. Billions of creatures are snuffed out every year in brutal and extreme ways. Without spending too much time on the grisly details, there is a simple reason that these places don’t have windows. Horror, with its ability to capitalize on the unspoken, the horrific and the violent which is all too often repressed in cultural discourse, can have a powerful role to play in bringing the violence of our treatment of fellow animals to light and forcing us to confront it. Here, let’s examine a few notable films, TV series, and novels, and see what they can tell us about the nightmare lurking in all of our grocery stores: the nightmare of meat.

The Midnight Meat Train (2008)

The Midnight Meat Train is not a subtle film. Adapted from the Clive Barker short story of the same name, it follows a photographer named Leon Kaufman (Bradley Cooper) who becomes obsessed with a mysterious man dressed as a butcher (Vinnie Jones) who he sees skulking around the New York City subway system at night. Soon he learns the hideous truth: that the man, known only as Mahogany, is responsible for a wave of disappearances that has struck the city. He’s been killing people with a meat hammer, night after night, then butchering and dressing their corpses just as he would a cow or pig. Then he hangs them from meat hooks in a subway car and delivers them through abandoned tunnels miles underground, where they’re ultimately eaten by ancient reptilian creatures. He is, in effect, the lizard-men’s wholesale supplier.

Vinnie Jones as Mahogany in The Midnight Meat Train (dir. Ryuhei Kitamura, 2008)

Barker’s plot is straightforward enough. It’s really just another example of the “serial killer on the loose” genre that’s been a staple of horror cinema since Alfred Hitchcock’s 1927 silent film The Lodger. What sets The Midnight Meat Train apart from a hundred other slasher movies, though, is the way it fixates on butchery and meat production as a motif. In both Barker’s original story and the film adaptation, the aesthetic presentation is deliberately excessive. The prose version exults in its descriptions of gore and mutilation, as if trying to nauseate the reader:

The meat of her back had been entirely cleft open from neck to buttock and the muscle had been peeled back to expose the glistening vertebrae. It was the final triumph of the Butcher's craft. Here they hung, these shaved, bled, slit slabs of humanity, opened up like fish, and ripe for devouring.

Likewise, in the film, director Ryuhei Kitamura cranks the gore dial up to 11 and beyond. In one memorable scene, Mahogany sneaks up behind his latest victim as the man stands talking with another subway passenger, and delivers a mighty smash of the meat hammer to the back of his head. We see a CGI eyeball pop out of his skull and shoot toward the screen, striking the camera lens with a dull splat. Then a second victim tries to run, only to slip on her compatriot’s rubbery eyeball, fall, and get decapitated.

In a different director’s hands, this could be so over-the-top it becomes comedic, and there is an element of dark, grand guignol humor here. But although the film shows copious violence and bloodshed, the carnage is also largely dispassionate. Where Friday the 13th’s Jason Voorhees kills for revenge or A Nightmare on Elm Street’s Freddy Krueger kills out of sadism, Mahogany is a cold professional. He doesn’t care who he grabs or how they die; all that matters is that his “customers” in the tunnels are fed and satiated. It’s the disconnect between the extreme violence itself and the lack of emotion in Jones’ performance that makes him uncanny. Even the environment of the subway cars is cold, all halogen blues and stainless-steel greys—a sterile space. At its core, this isn’t a story about people at all. It’s about an industrial process that renders people into food.

The concept of a person becoming meat has always been one people find viscerally disturbing. It’s the subject of children’s stories across a dozen cultures. When the giant chases Jack down the beanstalk, he wants to “have his bones to grind my bread.” Ditto the wolf and Little Red Riding Hood, or the devouring rakshasa of Hindu mythology. But why should humans find being eaten uniquely horrifying, as opposed to just being stabbed or bashed against a rock? We’re dead in any case, but being consumed has an undeniable particularity to it. In her book The Eye of the Crocodile, ecological philosopher Val Plumwood offers a possible answer. She describes a harrowing experience where she was almost eaten by a crocodile in rural Australia, and the reflections it prompted:

For a modern human being from the first, or over-privileged world, the humbling experience of becoming food for another animal is now utterly foreign, almost unthinkable. And our dominant story, which holds that humans are different from and higher than other creatures, are made out of mind-stuff, has encouraged us to eliminate from our lives any animals that are disagreeable, inconvenient or dangerous to humans. This means, especially, animals that can prey on humans. In the absence of a more rounded form of the predation experience, we come to see predation as something we do to others, the inferior ones, but which is never done to us. We are victors and never victims, experiencing triumph but never tragedy, our true identity as minds, not as bodies.

This cultural assumption that humans are innately distinct from, and above, other animals is deeply ingrained over generations, in both religious and secular narratives. That’s why The Midnight Meat Train’s blood-soaked excess is so effective. It breaks through that wall of ideology with the bluntness of a literal hammer, reminding us that we are indeed flesh, the same as any other creature. To memento mori, it adds memento carnem.

There’s a precedent here from the history of horror and science fiction. Over the years, plenty of literary scholars have pointed out that H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds functions as a metaphor for British imperialism. With his giant mechanized Martians and their heat rays, Wells showed the British public what it would be like to be invaded and colonized by foreigners with vastly superior firepower. For his part, Clive Barker has written online that “being a vegetarian has lost me more friends than being a gay man,” and it seems clear that his chosen diet is an influence on his art, just as his sexuality shows up in the BDSM-inspired imagery of films like Hellraiser. With The Midnight Meat Train, Barker and Kitamura do for industrial slaughter and meatpacking what Wells did for empire.

For most of its runtime, the film places us in the animal’s-eye view, haplessly watching as our fellow creatures are gutted and rendered into sides of meat hanging from hooks. It’s only at the very end, when we meet the malignant reptilians hiding in the shadows, that we meet ourselves: the consumers whose hunger makes the carnage happen. The film poses a simple, yet ghastly question: how would it be if another creature treated us the way we treat animals? And if anything, it understates its case. Compared to the vast hangar-like charnel houses operated by Hormel and Tyson Foods in the real world, Mahogany’s subway operation is small and quaint. If that knowledge is enough to put us off our movie-theater hot dogs, we only have ourselves to blame.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

Tobe Hooper’s 1974 film, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, is regularly thought of as one of the most violent horror films of all time. Made on a paltry budget of less than $140,000, the film has become the blueprint for decades of slashers that followed it. It follows five teenagers in rural Texas, concerned that someone is digging up the bodies of the dead and desecrating their corpses. After picking up a giggling hitchhiker and encountering a gas station with no gas, the teenagers come across a farmstead, not too far from the old abattoir which still seems to supply some modicum of employment. At this old farmhouse, decorated with animal bones, the teenagers come across Leatherface, a former slaughterhouse worker who wields a chainsaw and meathook to genuinely skin-crawling impact. The film’s low budget means much of the worst violence is only suggested or shown off screen, but the production design makes use of real life animal corpses and blood as a means of keeping the costs down. Filmed in the heat of a Texas summer, the cast and crew spoke regularly about the sheer stench they had to work within: "Aside from being gruesome," remembers Leatherface actor Gunnar Hansen, "the set also stank. In that heat, the bones and hides and animal parts were letting off a rich mix of fumes."

Marilyn Burns, who plays legendary “final girl” Sally, has similar dark memories of the production: "I remember just being tied up," she says, "being screamed at, having the smell of headcheese[…] and the room itself, the chicken, all the other decaying meat, the decaying set, the decaying crew." As Mark Steven details in his essay on the film, “Between takes, the cast and crew would flee the set, even if only for the shortest reprieve, to seek fresh air or to vomit.”

The film reveals that Leatherface and his family were once slaughterhouse workers, who, over time, became desensitized to violence by their work. “My family has always been in meat,” as one famous line from the film runs. The film understands that Leatherface and the rest of the cannibal family don’t see a big jump from working in a slaughterhouse, tearing apart the flesh of cattle, to murdering humans.

The climactic dinner scene from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (dir. Tobe Hooper, 1974).

The film was remarkably prescient in many ways. Research shows that actual slaughterhouse workers are psychologically traumatized by the work; there’s also the exploitation of child labor, and a wide range of horrifying injuries. OSHA data from as far as back 2018 shows an average of two amputations a week for employees of American meat plants—numbers which are almost certain to rise as DOGE-era cuts and deregulation continue to bite. If the owners don’t care about animal life, they don’t care about human life much more; it’s all a process of converting flesh to profit.

The film also shows what happens when a meatpacker or slaughterhouse abruptly leaves town, leaving everyone without jobs. Pioneering horror film critic Robin Wood wrote at the time that Leatherface and his family were a kind of degraded proletariat, struggling to survive in the backwash of deindustrialization. The stagflation of the 1970s that formed the context of the film’s production shows what is by now a familiar story. Entire families and communities that exist at the whim of one company, left to scramble for whatever they can find. The corollary of deindustrialization is desperation. It’s notable that Leatherface and his family don’t seem to enjoy the violence they inflict. As the old man of the family puts it, “I just can’t take no pleasure in killing. There’s just some things you gotta do.”

Hannibal (2013)

Where The Texas Chainsaw Massacre envelops its viewers (and its cast) in a squalid world of rot, heat, stench, and animal bones, NBC’s 2013 TV series Hannibal inhabits a polar opposite aesthetic world. The show is producer Bryan Fuller’s take on Dr. Hannibal Lecter, now portrayed by Mads Mikkelsen instead of the iconic Sir Anthony Hopkins. Formally, it’s a crime drama, with Lecter—who hasn’t yet been caught—helping detective Will Graham and the FBI catch other, lesser serial killers. And paradoxically given its subject matter, it’s a thing of beauty. From the rich colors and lighting of the sets, to the exquisitely-tailored costumes, to the classical music and opera that pervades the soundtrack, every detail is calculated and artful. Unlike with most crime and horror shows, it’s as much a sensory experience as a narrative one; you could watch some episodes on mute, and still appreciate them. Nowhere more so than in the frequent cooking scenes.

Most episodes of Hannibal contain at least one scene of the not-so-good Dr. Lecter preparing a meal for someone, whether it’s a “protein scramble” for breakfast or an elaborate roast for a dinner party. Sometimes the meal consists of human flesh, with Lecter taking a voyeuristic pleasure in watching his guests commit cannibalism unawares. Sometimes it’s animal meat, used as a metaphor for human murder. (Of a rabbit: “he should have hopped faster.”) Sometimes it’s left unclear, with the narrative tension being whether it’s one or the other. But in every case, the most disturbing thing in Hannibal is that the food looks good, even after you know what Lecter has been putting in it. The show had a “food stylist,” Janice Poon, on staff to design all the dishes, together with consultancy work from celebrity chef José Andrés. The result is a jarring dissonance. We are watching a man murder and eat other human beings, but with the visual language that’s usually used to show Gordon Ramsay making a beef Wellington for Christmas dinner.

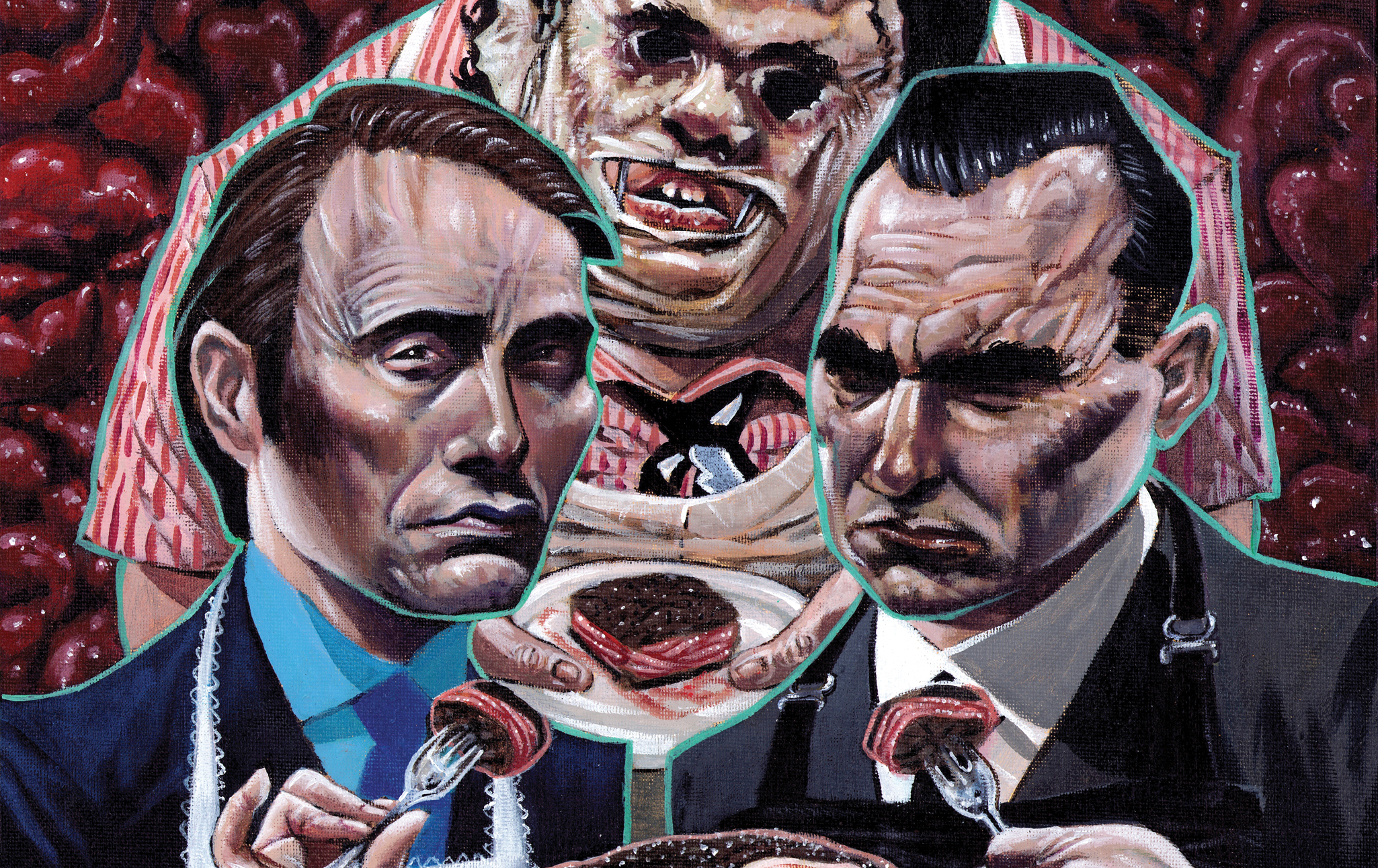

Dr. Lecter serves some suspicious-looking filets. (Hannibal, 2013)

These visual choices break down the age-old cultural assumption that benevolence is necessarily aesthetically beautiful, and conversely, that evil is necessarily aesthetically ugly. In reality, no such correlation exists—and beyond that, the aesthetic markers associated with beauty and “high” culture are often inextricably bound up in cruelty. Unlike the Texas Chainsaw family, Hannibal is not just a cannibal, but a gourmet. Like American Psycho’s Patrick Bateman, he’s an example of what Blood Knife magazine editor Colin Broadmoor calls the "psychopathic aesthete”:

He is a “sophisticated European” (the truest arbiters of taste for many Americans) and “classy.” Hannibal is “refined.” Unlike with Patrick Bateman, the creators never question Hannibal’s tastes, but the character exhibits the same sense of aesthetic superiority and self-satisfaction. The difference is, in Hannibal, the audience is expected to at least somewhat buy into this idea of Hannibal’s superiority. When Hannibal murders someone because they violated one of his aesthetic principles (perhaps by being rude or unkempt), the audience accepts that as an explanation in a way that they would not if he listened to Huey Lewis and Phil Collins. This is because the things that Hannibal finds aesthetically pleasing, like rare wines, classical music, and opera, are signifiers of cultural capital in our own society.

Indeed, the cruelty and the aestheticism are often one and the same, as seen when Lecter serves foie gras. In this case it’s definitely goose-derived, but as viewers we’re meant to see it as simultaneously attractive and repulsive, in the same way as the human lungs that were sauteed in wine in a previous episode. Again, the (ultimately illusory) distinction between human and animal is dissolved. The person who lost the lungs suffered horribly, and so did the goose who was force-fed until its liver swelled. But instead of observing this common pain and concluding that eating either being—human or avian—is appalling, Lecter has observed it and concluded that eating both is acceptable, because he values aesthetics more than empathy. It’s a calculation, the same as the one that says a calf and its mother’s suffering is worthwhile if a rare veal steak is the result. To any non-vegetarian viewer, the show poses a sinister question: if you find that steak seductive, are you sure you wouldn’t eat a human under the right circumstances?

This imagery is also loaded with real-world political significance. In his landmark essay On Social Sadism, the Marxist science fiction and horror writer China Miéville argues that the delight the rich take in their luxuries is often directly linked to the suffering of the poor; as a key example, he points to the “homeless” themed costume parties that law firms specializing in foreclosure held during the 2010 financial crisis. In these moments, “Class spite, always present, stops half-heartedly disguising itself with bowdlerising condescension.” But we can apply this logic of “social sadism” to the killing and consumption of animals, too.

As an objective matter, foie gras—or veal, or caviar, or any other elite delicacy—doesn’t taste any better than, say, a nice fried eggplant. There’s no particular reason it should be these foods that our society, class society, designates as the fare of the rich and refined. No reason, that is, except for cruelty. Caviar is rare, true, but it also inflicts unusual pain—“Workers often cut female sturgeons open and remove their eggs from their ovaries while they’re still alive,” notes PETA. Same with veal, and with artificially fattened goose liver, and with the ortolans—small songbirds—that are sometimes consumed whole in France. (See Troy Vettese’s recent article on animals and socialism for more on that.)

The cachet these culinary commodities hold is inseparable from the fact that a high cost in pain is needed to acquire them. In this way, Hannibal Lecter’s delight in his human meat is only an exaggeration of a real phenomenon. Every chef cooking lamb chops tonight is a mini-Lecter, and so are the diners dropping hundreds of dollars per plate. By the same token, if we were actually going to have a food system free of cruelty, it would mean no longer treating a food’s aesthetic qualities as a legitimate reason for it to exist or be produced. The demand and desire for things like veal would simply have to be suppressed, just as a cannibal’s desire for human flesh is now. And like with Clive Barker’s vegetarianism, it’s notable that Bryan Fuller is a pescatarian who has made TV ads for PETA, designed and shot to look like they came straight from the show. All of this isn’t even subtext; it’s just text.

It isn’t just film and television horror media that can function as an allegory of the violence of industrial meat production. Horror novels, too, have explored this relationship to powerful effect. Take Michel Faber’s 2000 novel Under the Skin. Its narrative follows an alien from another world who has assumed human form as she drives around the countryside of Scotland picking up hitchhikers. The alien creature, who goes by the name Isserley, initially approaches her work with some degree of professional pride. The people abducted are taken back to a central base of operations, drugged, fattened up and shipped off the planet back to another world where human meat, which the novel calls voddissin, is considered an expensive delicacy.

There are echoes here of Damon Knight’s famous 1950s era sci-fi story “To Serve Man,” which was later turned into an even more famous episode of The Twilight Zone. However, as the novel goes on, Isserley cannot help but begin to recognize the commonalities between herself and the humans she abducts. At one point an imprisoned man, who is being fattened up in one of the pens that Isserley’s victims are kept in, writes the word “mercy” on the ground—forcing her to pretend not to speak English so that she, and the other alien creatures working in this grisly abattoir, can keep themselves in a state of deliberate ignorance, unable to admit that humans are just as intellectually sophisticated as they are. At another point she demands to see what happens during “processing.” She’s left terrified and revolted as she watches a man be castrated and have his tongue ripped out.

The entire arc of the novel is the slow dawning realization that Isserley comes to: despite using humans for food, she feels a great affinity for them, recognizing them as sentient creatures, uncomfortably close to herself. Despite all the attempts to maintain her ignorance the more time she spends with humans the more she comes to see herself in them, preferring at the close of the novel her own self-annihilation than continuing to brutalize other living creatures.

The novel follows Marcos, a vegan who works in a slaughterhouse to support his family. Estranged from his wife and emotionally traumatized from the death of his son, he starts sleeping with a woman who has been bred for consumption. He names her Jasmine, and though the novel heavily implies she cannot consent, she becomes pregnant. The true impact of the novel is expertly delayed until its very final pages, in which Marcos is revealed to have used Jasmine only to replace his own dead son with a new living child, as a way of reconciling with his wife, Cecelia. After the baby is born, Marcos takes Jasmine to the barn, readying her for slaughter.

Ultimately, Bazterrica’s novel sees the meat industry as synecdoche for capitalism itself in which every human emotion and interaction requires the consumption of the other. In this it shares something with Marxist-feminist writer Nancy Fraser’s critique of capitalism:

For Fraser, capitalism is predicated upon endless consumption, a system under which every single scrap of life must be fed into its maw. And as Bazterrica’s novel suggests, when we’re happy to see this kind of violence inflicted on animals, we’ll take to inflicting it on our fellow human beings with a grim, all encompassing enthusiasm.