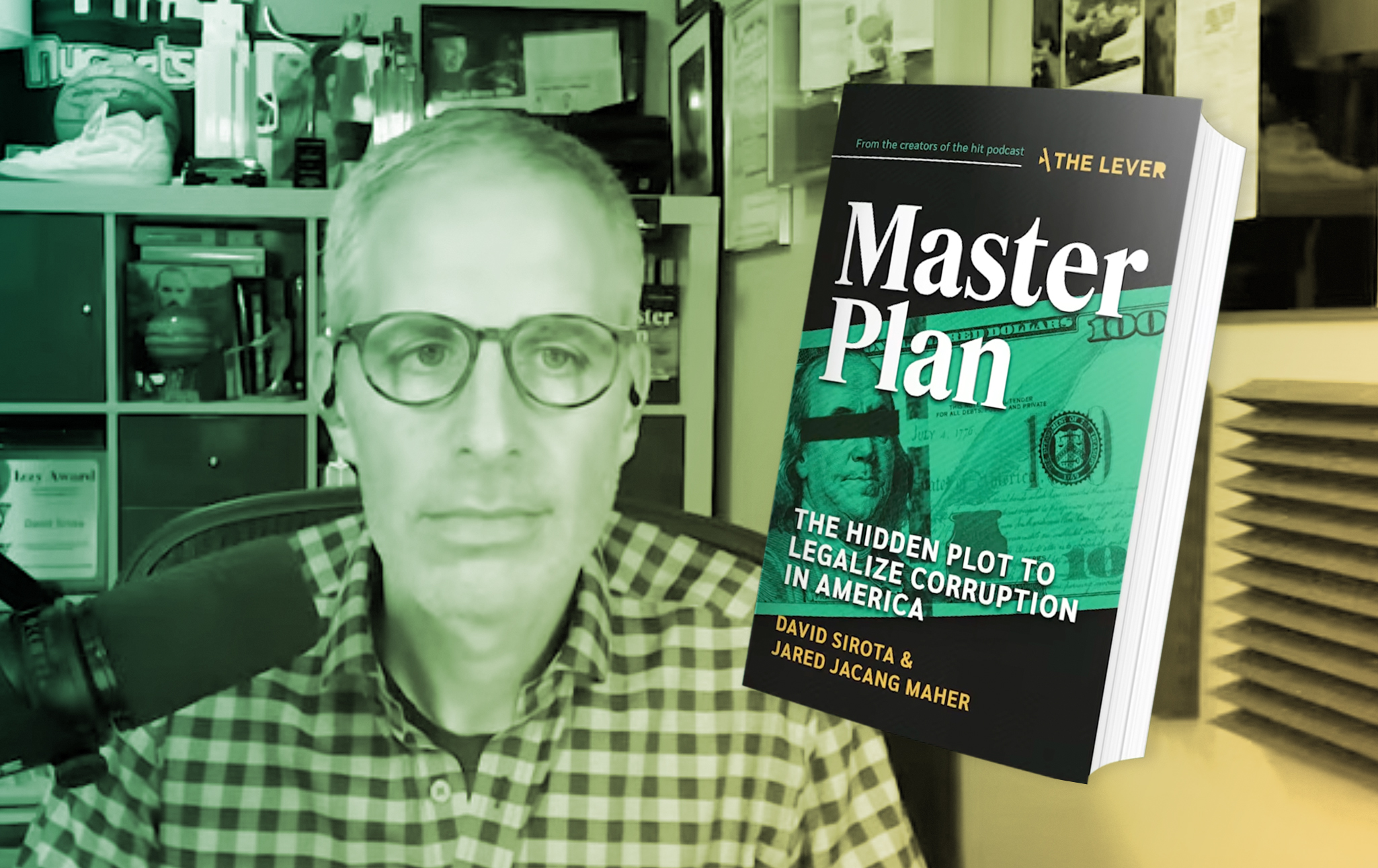

In his latest book, the journalist traces a half-century conspiracy of deregulation, dark money, and captured courts.

Sirota

Right. So Ralph Nader is running groups like Public Citizen and various constellations of public interest groups, and he came into prominence with his scrutiny of the auto industry. They were essentially grassroots groups that were having a lot of success, pushing the government to pass all sorts of basic corporate regulatory reforms that didn't really exist before that. So we're talking about auto safety rules, food safety rules, financial rules, all the things that corporations didn't want. They didn't like pollution rules and the like.

So Nader is having a lot of success, and this is making many corporate types mad, including Lewis Powell, who writes this memo—people have probably heard of the Powell Memo—for the Chamber of Commerce, the most powerful corporate lobby group in the country at the time, saying essentially that Nader types are a threat to free market capitalism and that this is an existential threat to corporate America, and corporate America needs to invest in a radical way in buying politics and media—essentially an entire infrastructure of communications and political spending that we understand to be now the modern conservative movement.

So he pens this memo. A few months later, he gets a call from Richard Nixon asking him to be the nominee for the Supreme Court, to which he says yes. As we document in the book, it's kind of unbelievable. It's believable and yet unbelievable that nobody had actually discovered it until we did. We found the photographs and a recording of the Philip Morris send-off party for Lewis Powell to the Supreme Court. Lewis Powell was on the board of Philip Morris, and this send-off party is where Lewis Powell is presented by tobacco industry officials with judicial robes emblazoned with tobacco industry logos. Walter Cronkite is there to narrate a sort of mock radio show valorizing Lewis Powell's life. They're very excited that their corporate guy is getting on the Supreme Court, and quite soon after, Lewis Powell is engineering rulings on the Supreme Court, first equating money with constitutionally protected speech, and then a ruling that Lewis Powell engineers kind of behind the scenes—an incredible drama there.

It's a ruling in a seemingly small case that extends those constitutional rights of corporations in their spending in elections—the Bilotti ruling that becomes the basis of the Citizens United ruling. So the point here, just to summarize, is that Lewis Powell pens this memo and then is put into the position to execute on it in a way that starts deregulating the campaign finance system, which Powell and his acolytes understood they needed to do to start getting their way. And this is the key point: they understood that they couldn't get the policies they wanted in a functioning one-person, one-vote democracy. Powell kind of lays this out, that essentially the public wants things that the elite doesn't want. We have a democracy problem here, so what we have to do is essentially rig the democratic process so that the small group of us who have lots of money can make sure the system stops delivering to people what they want.

Robinson

In that memo, he's essentially saying that with the environmentalists, the anti-corporate types—the students, the young people—we have a risk of too much democracy. We need a corporate fight-back plan. You also note in here that when he was a tobacco lawyer, he was actually part of the plan to bury the health risks of tobacco use in the corporate war to make sure people didn't know that cigarettes would give them cancer.

You covered a lot of interesting new documentation from a Gordon Liddy memo in which the Nixon team is conspiring about how to evade the new election regulations. But what I want to talk to you about is the influence of the Powell Memo, because you've mentioned there that he is a corporate lawyer, and he writes a memo that essentially says: We are at great risk from the Ralph Nader types, and we've got to have a plan to fight back. We've got to take over the schools, take over the courts, and we've got to foist free market ideology on Americans, whether they like it or not.

The defense against this always was, but it was never influential. He wrote it, sure, and yes, it reads like a corporate conspiracy, but it didn't get acted upon. This is just one guy's memo. But one of the things that's so interesting about what you do in Master Plan and all the stuff you uncover, which I had no idea about, is what happened next. How the Powell Memo itself circulated and the influence that it had, which was real. And you've done a hell of a lot of work to try and figure out who actually read it.

What did they actually do once they'd read it? I think that's some of the most interesting parts of the book. So give us a little preview of what happened to this thing.

Sirota

You're right to mention that for years the idea was that Lewis Powell wrote this screed, and it was sort of like the 1970s equivalent of a random Reddit thread. He wrote a screed, and then it didn't go anywhere. Well, that's actually not true, not even close to true. It's actually the opposite of true, as we discovered. For instance, just one example here.

Joseph Coors, the head, the scion, of the Coors Brewing Company, had an interview in which he said that he was stirred—originally "stirred", that's his word—into political philanthropy when he read the Powell Memo. And of course, Joseph Coors is the founding funder of the Heritage Foundation. The Heritage Foundation is the creator of things like Project 2025. The original Project 2025 was Mandate for Leadership, the 1980 agenda. Ronald Reagan implemented many of its directives.

So I cite that as one example, but it gets actually a lot more specific here. So we document a series of secret meetings that the Chamber of Commerce begins convening, meetings about how they are going to implement the Powell Memo. There's a secret meeting, for instance, in of all places Orlando, Florida, at Disney World, where Gerald Ford is flown into by the lobbyist for US Steel. It was a meeting that discussed, in part, campaign finance issues. This is one of the big links here, where they're talking about an amendment that they're trying to add into campaign finance legislation that is moving forward amid the Watergate scandal.

Gerald Ford, of course, is the House minority leader here, and guess what ends up happening? The Republicans end up adding language to the original Federal Election Campaign Act that allows for the creation of what we now call corporate PACs. So in other words, one example here is a secret meeting where they're talking about how we best implement the Powell Memo. They bring in the House Minority Leader, Gerald Ford, who's about to become president. And what comes out of this is they want an amendment to make sure that the campaign finance reforms that are moving forward in Congress amid the Watergate scandal create a loophole for corporate spending. Now we trace a bunch of these meetings.

There's a later meeting after Ford becomes president, soon after Ford is sworn in. We found the minutes of the meeting, in which they're going through all of their successes at that point, 1974, of what they are doing. We're talking about everything from financing a movie—a separate movie, by the way, that ends up starring Jimmy Stewart, if you can believe it; we found the audio of that—to financing a nationwide ad campaign in partnership with the Ford administration and in part funded by the US government to promote free market capitalism, essentially with government money and in partnership with corporations and the Ad Council. Remember Lewis Powell said: We have to start fighting back against Ralph Nader and these sorts of lefties.

Well, three years later, at this meeting, they're talking about how they are moving forward with this nationwide ad campaign. We found the ad campaign. It's unbelievable to see. You can see it in the book, but you can imagine in your mind what this is. It is basically that. They're talking about radio actualities, newspaper columns, and advertising campaigns. The point is it's the opposite of true that Lewis Powell's memo went nowhere. It was very, very clearly the inspiration for a lot of what we understand to be the conservative infrastructure that was pivotal in taking over the country.

Robinson

Every time we lefties get to talk about corporate power, we're accused of being conspiracy theorists. Tom Wolfe famously said in response to Noam Chomsky, Chomsky thinks there are smoke-filled rooms. I know for a fact—I've been in the elite—there are no smoke-filled rooms.

This chapter, The Secret Task Force, is jaw-dropping, because if you didn't have the documentation, it would sound like pure conspiracy, but literally, they advertised it themselves. You've got a photocopy of the issue of the US Chamber of Commerce's magazine where they talk about what their task force on the Powell Memorandum, which is what its name is, has been doing. They convened all of these heads of corporations, as you said, at Disney World for a conference. Executives from General Motors, CBS, 3M, JCPenney, and more get together for a task force.

You say, yes, there was an actual Powell Memo task force at Disney World, where representatives from corporations plotted how to fight back against the regulatory push that had been, in their minds, stifling them.

Sirota

The list of attendees is really, to me, one of the smoking guns here. And I think it's worth taking a moment to mention some of the heads of the largest media corporations in the country. This was one of the most fascinating revelations to me: rather than exposing what this movement is planning and doing, you have the heads of media corporations that run journalism divisions actually participating in this. That sounds insane, but we found a letter as an example from CBS President Arthur Taylor, who is writing to a college president who is one of the key connectors in this, saying, essentially, the Powell Memo makes great reading. I agree with everything that it's saying; free market capitalism is under attack, and I am working to correct—"correct", that's the word he uses—the situation at CBS News, with some success.

So when you think about all that's going on in media today—the billionaire takeover, Bari Weiss—this started 50 years ago. This is really where it started. And again, to tie it back to campaign finance, they implicitly understood that ultimately they could not get the policies they wanted unless they deregulated the campaign finance system and anti-bribery laws so that they could put in place the elected officials they wanted, who would do what they wanted.

Robinson

People may be familiar with the rough contours of political history over the past 50 years. They may know that the '60s moment gave way to the Reagan Revolution and the neoliberalization of the Democratic Party. And they now see a fully conservative Supreme Court and an openly corrupt administration as the culmination of these trends.

But how did it all happen? Why did we end up in this place? And so you go back and you tell us, where did the Heritage Foundation come from that gave us Project 2025? Where did the Federalist Society come from that gave us the modern Supreme Court? Where did the American Legislative Exchange Council that pushes all the right-wing legislation come from? Where did this all come from? You trace it back to its origin point, and you show that it is, in fact, part of a plan.

Sirota

It absolutely is part of a plan. And what I really valued in doing this project, and why, frankly, it took so long, was because this is all based on documents, photographs, transcripts, audio—in other words, sort of unimpeachable evidence.

This is not me just spinning a yarn here. And in fact, we did an audio series about this, and the book builds off that audio series and expands on it greatly. And one of the reasons I wanted to do that was because I essentially wanted a paper archive. I wanted this to exist in physical form with footnotes, etc., that people could verify for themselves. You don't have to trust me here. Everything is footnoted for you to see, because I don't want to be accused of it being a conspiracy theory. They wrote it all down. The amazing part is they wrote it all down, and it reminds me of the line from Adam McKay's movie, and I'm paraphrasing here, They're divulging secrets—they're not admitting things, they're bragging about it!

That's the point. There's a lot of bragging here. I just have to tell folks about this one scene that still to this day blows my mind. At one point a young operative named Roger Ailes pops up at a couple of these Powell Memo task force meetings, and one of the people who's there is writing about how amazing a presentation he's made. What this person, recounting what Ailes is presenting, says is that Ailes told the assembled group of corporate leaders that they need to start remembering that they are advertisers—they essentially pay media companies to advertise—and they have not properly leveraged their position as advertisers to get the kind of news content that they want.

For years, a lot of us out here were asked, "How could you be saying that media owners or advertisers have any influence over the media properties they own?" Here is evidence of Roger Ailes—who goes on, of course, to create Fox News—saying, Hey, you all here are advertisers. You need to use that leverage and that pressure to get the kind of news coverage that you want. He screamed the quiet part out loud.

Robinson

Yes, well, this whole book is making the quiet part loud through all the memos and court decisions. A lot of the book is about the courts and the series of court decisions. Because one of the things about courts is that they are the least democratic branch. They are the branch where a small number of unelected people can basically make a decision that binds all the other branches. They can overturn legislation.

A big part of this corporate movement was a legal strategy, and that involved, in the early days, as you said, actually managing to get this tobacco lawyer on the Supreme Court so he could actually begin to roll back the limited campaign finance laws that we had. Basically, over the course of 50 years, through decision after decision—some of which were high profile, some of which were lower profile—we got to a point where we are back to essentially a world in which the few regulations that we have are not [sufficient]. We had Elon Musk just bragging that he bought the election for Donald Trump.

Sirota

Yes, and two points on that. I mean, one thing people are going to take away from this book is the old George Carlin quote, "It's a big club, and you ain't in it." It is a relatively small group of people here. I just think back to, for instance, the notion that money is constitutionally protected speech, as opposed to money in politics buying votes. That's a big distinction. Is money in politics a corrupting force that buys votes, or is it constitutionally protected speech? The Buckley v. Valeo case said it's constitutionally protected speech. That radical theory—at the time, a highly radical theory—that money is First Amendment speech was pioneered by none other than John Bolton. John Bolton—the John Bolton; we're talking about the same John Bolton—was a legal advisor to the plaintiffs in that case.

Obviously, William F. Buckley's brother, who'd been elected senator, was the namesake of that case. That is the basis for everything that was to come, and again, it came out of this movement. Fast forward to today. As we show, 50 years later, you now have JD Vance, as we speak, spearheading a case at the Supreme Court. Very few people have talked about it. It's happening right now. JD Vance is at the Supreme Court, spearheading a case aiming to give the now six-to-three conservative majority a chance to eliminate whatever they left standing in the Citizens United decisions.

Remember, Citizens United basically said corporations and independent expenditures cannot be regulated because they are not a corrupting force, are supposedly independent, and are protected by the First Amendment. Some things were still allowed to remain, some basic campaign contribution limits. JD Vance is now essentially trying to conclude the master plan with a case at the court. So the point is, this all still continues today.

Robinson

And just to note, I believe you have done some of the only reporting on that. Was it in Rolling Stone that you had a piece on it?

Sirota

Yes, Rolling Stone. We did a big piece on this. There's also another case at the court that's aiming to, once again, narrow the enforceability of anti-bribery laws. If you can believe it, the plaintiff is represented by a major Trump-connected law firm. Trump's former solicitor general is representing that case. And essentially, if you can believe this—I'm not exaggerating here.

Remember, the Supreme Court has already now ruled in multiple cases trying to limit the bribery laws, the most recent one saying that if a government contractor gives a payment to a politician after the politician has given the government contractor a contract, it's not necessarily bribery; it is a gratuity. That literally is now the Supreme Court precedent.

Robinson

If you get the policy before the money, rather than the money before the policy.

Sirota

Right, if you sequence it correctly, it's just a tip. It's not a bribe. Now we're in a situation where this new case says, essentially—remember the story of Donald Trump reportedly saying to potential oil donors, If you give me a billion dollars, I'll give you a bunch of policy favors? This is in the 2024 campaign. This case cites that this kind of behavior is so pervasive, so ubiquitous—and they say it as if this would be a bad thing—that you could imagine a prosecutor trying to prosecute that even though this is just what politics is.

In other words, you have a case that is essentially making the David Foster Wallace argument that we discussed at the top here, that this is not corruption. This is the way it works. This is the water we all swim in. And what the Supreme Court has to do is say that this kind of behavior is not prosecutable. That's where we are in this master plan.

Robinson

Now, David, in thinking about how corruption works in Washington, there are really egregious, obvious examples, like Elon Musk funneling money into Donald Trump's campaign, and then when Donald Trump gets elected, he puts Elon Musk in and gives him his own agency and says, Have at it, do what you like with the federal government. Or there's the example of, as you mentioned there, Donald Trump saying to the oil executives, Give me a billion dollars, and I'll make sure that we never have a climate policy again. These are very obvious quid pro quos.

And I think there's no plausible deniability here, but obviously that's among the least subtle of the ways in which corruption works, and you understand how the less obvious forms work. And Hillary Clinton, I think, famously said, Well, no one can ever point to an example where I changed a vote because of money. So can you tell us, aside from the really easy-to-understand examples like what Trump does, how this kind of everyday corruption changes policy?

Sirota

I'm so glad you asked this question, because yes, you're right. Donald Trump has made things so explicit. There's no pretense anymore. And I think in a certain way, that's good. I do think it's a clarifying moment to say that Donald Trump is both a pathological liar and yet incredibly honest in his brazenness. He's not even trying to pretend. So let's set that aside for a second.

I think what you're getting at is the kind of soft corruption that really defined politics in the lead-up to this and oftentimes defines politics sort of one level below the brazen and explicit. My first book was actually about this many years ago, called "Hostile Takeover."

Robinson

Yes, great book. It still holds up.

Sirota

It still holds up. Thank you. The point that I tried to make was if you can control the discourse, control the terms of the debate, and make sure the parameters of the possible in politics are options that you, an oligarch, or you, a corporation, find pleasing or helpful, then you don't have to stuff cash in envelopes. You don't have to do explicit bribery.

So if you essentially own the media space to control what is considered a legitimate and politically realistic idea and what is not, if you can surround legislators with not only personnel who are going to give them what you want to give them, but also create the information environment around them—think tanks, policy proposals—and know that the campaign finance system, at minimum, buys access—and by that, buys you access and keeps others who can't pay out—then you don't necessarily have to walk into a congressman's office and give them an envelope of cash. Because you've essentially put them in a hermetically sealed bubble of everything that you want.

And so that's the way really pervasive soft corruption works on a day-to-day basis, and I think it's really still not all that well understood. I think when Hillary Clinton says something like that, she's sort of playing on the idea that it's not so explicit, even though it's pervasive. It's all around you, so you can't point to one specific thing. To be honest, the person who talked really eloquently about this in the past was John McCain. John McCain had been involved in the Keating Five scandal, which was essentially an influence-peddling scandal, and he decided to politically manage that scandal and survive it, but with the zeal of a convert. He came out of that scandal saying, You know what? Essentially: I was wrong. I screwed up. That was bad, and now I'm going to essentially be a crusader against the system that I was caught in and call it out for what it is.

Robinson

What he had done was essentially be part of a group of five senators who had this influential, rich constituent, Charles Keating, who had donated to them. And when the federal government was looking into Keating's activities for possible evidence of illicit activity, he called his senators that he bought and said, Could you go and have a word with the federal government? And they did. They went and sat down with the regulator and said, Could you lay off this guy? which they did.

Sirota

Do you remember Charles Keating's quote? It's an incredible quote. I'm going to paraphrase it here, but it was something to the effect that when they asked him, Did you buy those votes? He was like, My money better have bought something. The whole point was, what do you think the money's for? That's what the money's for.

Robinson

Right. So McCain knew full well exactly how it worked. He knew he had been essentially bought and that he'd been embarrassed by it. There was a recent interview with Barack Obama on Marc Maron's podcast, and Barack Obama defended his failure to push for single-payer health care. And he said, Well, we didn't have the votes.

And I seemed to remember when he said that, a reporter, at some point, had reported a quote from Barack Obama back then where he had said that actually his opposition to single-payer health care was that it would cost too many jobs in the private insurance industry. I think you are the person who reported that.

Sirota

That's correct. So that's absolutely true. It was one of the most disillusioning interviews I've ever had in my entire life. So, long story short, I did a profile of Barack Obama in, I think, 2007, and we were talking about how he had said on his Senate campaign: We need single-payer health care. The only thing standing in our way is we have to first get a Democratic House, a Democratic Senate, and the presidency.

So obviously, when Barack Obama is elected president a few years later, they have a Democratic Senate, a Democratic House, and a Democratic president. But in the interim, in between that, before he became president, he had sort of said, I'm not sure if I'm for single-payer anymore. He sort of backed off it.

And around 2007 I said, Well, you said all we have to do is get a Democratic president [and congress]. Why are you already backing off it?

And he literally said this: Now I'm a senator, and what am I going to say to the people in Illinois who work in the insurance industry? And it's in the article, but I was like, wow, that's your argument?

Robinson

We've got to preserve the bullshit job. We don't need these jobs, but...

Sirota

It's an incredible thing, and I think my takeaway from it is and was at the time, and now putting it together with what he said on Maron's interview, it's not the jobs, it's the money; it's that he knows the insurance industry will come after him. And I think this gets to, to go back to your question about soft corruption, it's very important to understand that there's a kind of silent way that corruption works, which is to say this: I had a senator say to me a year ago, "Look, if I have a bill that takes on an industry, the political challenge is not only that the industry is going to spend against me. It's that all that industry has to do is shake its pocket change at other senators to keep them away from my bill."

Let's use the crypto industry as an example. The crypto industry spent a bunch of money in the last election and a bunch of high-profile races to defeat what it perceived to be its critics, and it was an investment not just in destroying the crypto industry's critics but in sending a message to all of Congress, saying, The next time we want something, we're not going to give you money, necessarily—all of you who are thinking about opposing us better get out of the way, or we're coming after you. So no money needs to even sort of be exchanged for the threat to define what is politically possible and what isn't.

And so to go back to Obama, I read what Obama said as a form of corruption: I was not willing to fight with a powerful moneyed interest knowing that it would be a hard fight, knowing that they would spend a lot against me. And I would extend that, by the way, to Obama on various things. Barack Obama campaigned as a populist, came into office, and quickly prioritized bailing out his Wall Street donors, while those same donors were mass foreclosing on millions of Americans, which, I would argue, created the conditions, ultimately, for Trump's ascent. But the point is, even in that example, in my view, a form of corruption is at the core. I'm not taking on my Wall Street donors. I'm prioritizing serving them while they destroy the lives of millions of people.

And in a certain sense, you can say, well, they gave him money for his campaign, but it's also the opposite. They didn't even have to spend after that because what that spending says to everybody in Congress is, You get in our way, and we're going to use our resources to buy the election you're running in to get you out of office.

Robinson

You actually open the book with the story of your own political disillusionment during the Clinton years, when you were with Bernie long before the rest of America got on board with him. And Bernie has long pushed for allowing Americans to buy prescription drugs from Canada. There was a bill, and it passed it.

Sirota

This is like 25 years ago, for folks who don't know.

Robinson

During the Clinton administration in the year 2000.

Sirota

This was a crushing story for me. This is my origin story. I'm working for Bernie Sanders. I'm a young person just out of college. I'm doing press for him. We're doing bus trips, taking seniors up to Canada to get more affordable life-saving drugs. Literally doing bus trips in order to spotlight this ridiculous situation where the drug companies are charging Canadians much lower prices than Americans.

And by the way, that's not to blame the Canadians. It's not like the drug companies aren't making money up in Canada. They're making good profits on the Canadian prices. They're gouging us here in the United States; these bus trips spotlight that.

Bernie ultimately gets a bill passed through Congress—not easy in 2000. The drug companies are the most powerful companies in politics. He gets a bill passed through Congress, making this legal. Finally, saying wholesalers can do this. You're not going to have to drive up to Canada, making this legal. The drug companies hate it. They end up slipping a tiny little loophole into the bill, saying that, okay, there's enough public support, and the Clinton administration can't stop it. Nobody could stop it. They just had to do it. They were shamed into doing it. And there's a loophole that says, before this goes into effect, the secretary of Health and Human Services has to certify that it's safe.

So we've won; we're celebrating, high-fiving. We did it. This is amazing. I'm a young person. Oh my god, the system actually worked. This is incredible. And sort of in the dead of winter, just a couple of weeks before Clinton is leaving office, they issue, right before Christmas, this short, quiet press release saying, We're not certifying this, essentially vetoing this bill after it had already passed and after the president had signed it.

Clinton had signed it, and yet, they're using this loophole to kill it on behalf of the drug industry. And here we are. I want to be clear, had that bill passed, it's not like it would fully solve the drug price problem, but we did everything. We played by the rules, and we won, and yet we didn't.

Robinson

But to avoid ending here on a completely dispiriting and disillusioning note, I would point out that one of the conservative lawyers that you talked to in this book was one of the architects of this strategy, James Bopp. I think he was inspired by or studied the strategies of Thurgood Marshall. He studied their strategies. They studied the strategies of the civil rights movement to undo all of these regulatory gains. The conservative legal movement studied the left and learned from the left, and what we can do is the same.

What's been done can be undone. It was different at one point. That's the inspiring thing, I think, in this book. Or the thing to take away is that things change because people make them change. What did they do? They developed a plan, they organized, they acted on the plan, and slowly, over the course of 50 years, achieved their objectives. They shifted power. Well, that doesn't necessarily only go in one way, and I think we need to look at the history. Everyone should learn the history that you lay out in this book and should do precisely the inverse: study their tactics, their methods.

Sirota

I completely agree, and I want to be clear, there are definitely ways to start unwinding this. I don't want to leave people thinking, I just read this to know how we got here, and there's no way out. I don't think that's true, and I want to give people things to think about and things that are actually in process right now. First and foremost, it's a huge problem. Money in politics: how do you deal with it?

First and foremost, to rescind the idea that money is speech, you have to try to pass a constitutional amendment to essentially repeal Citizens United. Various states have expressed their support for this. There is a constitutional amendment in Congress. It was recently reintroduced; that is something real. It's not pie in the sky. It will take a long time. As we wrote about in Rolling Stone this week, there's a state-based effort where the argument is that states are the ones that decide whether corporations get the same rights as human beings. In other words, that whole idea that corporations are people is actually the Supreme Court basing that idea on states granting corporations that.

The idea is that if you change that—and in the past, states didn't always do that—states have the right to say, Corporations have these powers, but they don't have these powers because their power flows from state law. So that means you can change state law to say corporations no longer have the power to spend in elections. And there's a ballot measure happening now in Montana, supported by luminaries of both parties, to change Montana's law. And one of the beauties of that ballot measure is that it doesn't mean you can just go to Delaware and solve your problem.

When a company outside your state operates in your state, they have to follow the laws in your state when they're operating there. So Montana passing its ballot measure is not going to solve the problem for every state, but it also doesn't mean that corporations that want to affect Montana politics can move to Delaware and get around Montana's law. It will solve part of the problem inside of Montana. Now, that means that blue states, through their legislatures, could do that kind of thing right now. States can also require dark money disclosure. That's another huge one. Arizona, a purple state, passed a ballot measure with 70 percent support requiring disclosure of spending, so at least you know who is spending to influence your elections.

And then the biggest thing of all, to my mind, is public financing of elections. Everyone who's listening to this knows who Zorhan Mamdani is.

Robinson

Oh, yes. When I interviewed Mamdani early in the race, I couldn't believe this when he said, We're going to get these matching funds of eight to one. And I said, What?

Sirota

Right. So everyone's wondering, what is the magic of Zorhan Mamdani? How did he win? How did he do this? Well, is it the charisma? Was it his slick ads? Was it his organizing? All of that's important, but I would argue Zorhan Mamdani could not have happened—there's no possible way he would have been where he is now—without New York's public financing system. And that system offers matching funds to small-dollar donations up to a maximum. But essentially it says if you can raise a certain number of small dollars to show grassroots support, then you can get a significant amount of public resources to run your campaign, resources that do not come from private donors with the expectation of legislative favors.

So my point in bringing up Mamdani is—and again, whether you're a Democrat, Republican, conservative, or progressive, the system itself doesn't discriminate for that—if you want more candidates outside the privately financed corruption system, whatever your politics are, then public financing systems, which exist in various cities and states, should be expanded. It's gotten very close to passing at the congressional level at various times in our history. It's a very old idea. Teddy Roosevelt was the first to suggest it.

I know there's an argument: You want to pay politicians? Why do you want to give politicians more money? Why would we do that? That's welfare for politicians. It's like, listen, we have the best political system right now that private money can buy. It's not going so well. Private donors love the current system. If we want a different system, we have to make sure that elected officials can get into that system without having to rely on those private donors. So, to my mind, that is one of the most, if not the most, important causes in our politics right now.

Robinson

When Mamdani was on the program, I was asking, how are you going to win? He was like, Well, fortunately, New York has this incredible public financing system. And then what he could bring in was capped, and then he had to tell the public—he had those great ads, which are like, Please don't send us money; give us your time. And he was able to focus on the building of the volunteer army instead of focusing on shaking people down for money all the time and telling people to give their time instead. And they did, and they all came out. So, yes, it's the piece of the story that people other than yourself often miss.

I want to recommend this book to everyone, "Master Plan: The Hidden Plot to Legalize Corruption in America." And I also just want to point out at the end here that David Sirota's The Lever is totally independent, and this book is a feat of years of research. You have a small team at The Lever. You have nothing like what The New York Times has, but you've been able to break stories consistently that The New York Times has missed. In fact, at some points, they've been parasitic on you, reporting things that The Lever got first.

You've been able to do that because you have a committed base of readers and supporters who understand that if we're going to fight corporate America's plot, we need media outlets that are not beholden to corporate America and that those are small, independent outlets like your own. If people don't read The Lever, subscribe to it. Go on there and see the kinds of excellent stories that they are breaking consistently, and listen to the award-winning podcast and read the new book, which is just being published today as we speak.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.