In college, when people found out that I was specializing in Irish history, I often got the question: “Are you Irish?” I never really knew how I was supposed to answer this. I clearly have an American accent. My most recent non-American-born ancestors, I suppose, were Irish. They were dour, middle-class Protestants from some weird evangelical sect, who immigrated to the United States just before Ireland got its independence in the 1920s, presumably because they were alarmed at the prospect of Catholic rule. (Of course, a few generations later they forgot the whole thing and intermarried with a bunch of Catholics, so, three cheers for the American Melting Pot, I guess). But I have no family members in Ireland, and no cultural connection to Ireland that I attribute to bloodline rather than mere intellectual interest. I do experience a profound emotional reaction to the combination of bagpipes and goatskin drums, which I sometimes find difficult to explain to people. But this, I think, is because of my unusually sophisticated musical taste, rather than some ethnic legacy.

Nonetheless, there are many people in the United States eager to proclaim themselves “Irish Americans.” Certainly, there are lots of people here with Irish ancestry—but there are surely nearly as many with English ancestry, and yet you don’t hear very much noise from “proud English-Americans.” This eagerness to claim “Irishness,” I suspect, is at least partly related to the vague notion that the Irish were an Oppressed People. This impression, in turn, largely springs from a kind of imaginative conflation of all Irish immigration throughout history with the humanitarian crisis immediately following the Great Famine in 1846. The reality, of course, is that a great deal of Irish migration was going on both before and after the Famine, and that not all of it was driven by starvation, or by egregious political oppression. Plenty of Irish came to the U.S. seeking fortune, adventure, and better opportunity, like many of the ordinary people demonized today as undeserving “economic migrants.” Some of them, like my Rennix forebears, were unsavory oddballs with no better reason for inflicting themselves on this country than their desire to join some strange religious cult in Pennsylvania.

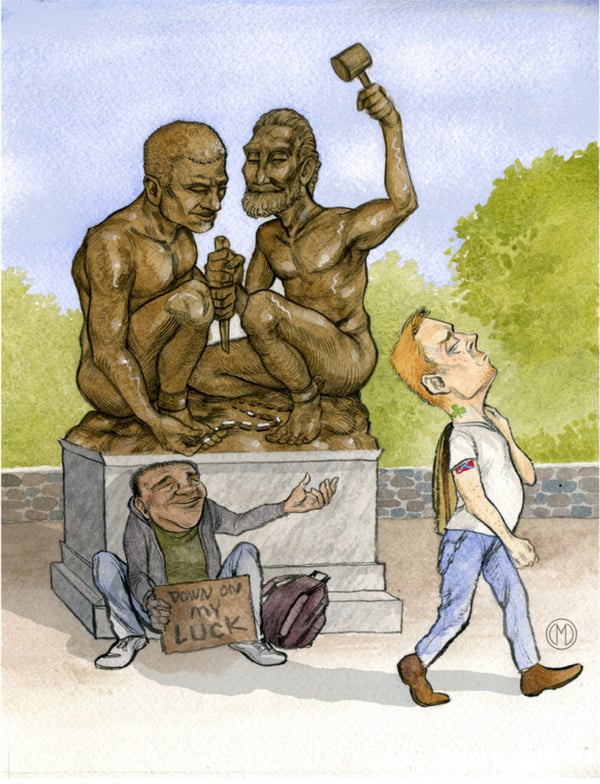

Surely, the reason that some Irish Americans like to imagine the Irish as oppressed—obsessing over the relatively brief but memorable era of nativist cartoons and “No Irish Need Apply” signs—is because there is cultural capital in oppression. For white people, especially—whether they’re working-class people looking for a deep historical explanation for their economic ills, or well-off whites looking to inject some DANGER into their personal identity—a whiff of racial oppression is a way to feel culturally distinctive. This attachment to a real or imagined heritage may usually be fairly harmless, and often it is quite genuinely felt. Sometimes, however, it manifests in deeply disturbing forms. Over the past few years, there have been a number of “Irish slavery” memes circulating the internet, often on white supremacist websites, but sometimes on Facebook pages of oblivious aunt-and-uncle types. For those of you who haven’t encountered this interesting phenomenon, the meme usually consists of an image of raggedly-dressed Irish laborers (or, sometimes, totally unrelated people, like emaciated survivors of Japanese POW camps), with accompanying text such as: “Irish were kidnapped, shipped in disease-ridden holds, traded like animals, and then whipped and worked on America’s plantations.” “Whenever they rebelled or even disobeyed an order, they were punished in the harshest ways.” “WHITE IRISH SLAVES WERE TREATED WORSE THAN ANY OTHER RACE IN THE U.S. WHEN WAS THE LAST TIME YOU HEARD AN IRISHMAN BITCHING HOW THE WORLD OWES THEM A LIVING?”

The pedigree of these memes, and a detailed interrogation of all the claims made within in them, has been expertly documented by Liam Hogan, a librarian at Limerick City Library, in a series of six articles published on Medium. These articles are fascinating reading, and a brilliant example of meticulously-researched history made freely available to the public. (History departments, take note! This is what the academy ought to be spending its time on!) Though the photographs are misattributed and the accompanying information almost always inaccurate, the memes do have a certain kernel of historical truth. There was a period during which some Irish people were transported to the Caribbean against their will, and forced to work as bonded laborers. This historical injustice has long been analogized to “slavery”: In 1915, the Irish socialist and revolutionary James Connolly wrote of how “native Irish” during the seventeenth century were “hunted to death, or transported in slave-gangs to Barbadoes.”

Under other circumstances, to characterize this forced labor as a form of “slavery” would be uncontroversial. But the “Irish slavery” memes want to go one further. They seek to promote a pseudohistory about an “Irish slavery” that was just as systematic and, in fact, qualitatively worse than the chattel slavery imposed on Africans and their descendants. The clear message of these memes, which are frequently deployed against Black Lives Matters activists and other racial justice advocates, is that black people are not entitled to the sympathy of Irish Americans, because Irish Americans have suffered more and whined less. Never mind that the number of forcibly-bonded Irish laborers in the Caribbean was fairly small, and that most “Irish Americans” aren’t descended from them. Pretending that there was a secret, widespread system of Irish slavery is much more glamorous than simply stating boring facts, such as that poor Irish suffered when they first came to America, or that poor people, including poor whites, suffer in America now.

It’s depressing to see this invented history being wielded as a weapon in the service of racial and political hatreds. If we want to look at the real history of Irish people in relation to slavery, a quite complicated picture emerges, in which the Irish acquit themselves at times well, and at times badly, depending on which individuals you are talking about, and whom you classify as “Irish.”

If we’re going to talk about the relationship between Irish identity and the history of slavery, we should probably start with St. Patrick. (And no, this is not simply because of my eccentric insistence on relating every topic back to the Middle Ages! I have reasons!) As we all know, St. Patrick is the premier mascot of Irish America. In every major city in the United States, people celebrate St. Patrick’s Day to honor their Irish heritage, or, at any rate, to vicariously participate in the Irish people’s historically troubled relationship with alcohol. Many Americans probably don’t know much about Patrick’s actual story, simply thinking of him as a crozier-wielding snake exterminator. Even those who do know Patrick’s biography have likely heard it too many times, until it no longer seems interesting or striking: the way many of us have heard the stories of, say, Frederick Douglass or Harriet Tubman so many times that we no longer appreciate the astonishing narrative arc of their lives. What the real-life St. Patrick had in common with Douglass and Tubman, of course, was that he was an escaped slave. This fact of his history, from what we can tell from his writings, formed a central part of his self-conception and his sense of moral purpose.

Indeed, Patrick—who lived in the 5th century AD—is quite a strange person to have become the chief global symbol of Irishness, because he himself was not Irish at all, and only ever referred to the Irish as a “foreign people.” Patrick was born Patricius, and grew up in Great Britain, which was then part of the Roman Empire. (This, to be clear, was many centuries before Ireland was a British colony.) Patrick was likely from a family of at least middle-class means: His father was a decurion, a local government official, and his grandfather was a Christian priest. We know few specifics about Patrick’s origins beyond these few facts, as most of the biographies and documentary traditions about him are deeply suspect. (They date several centuries after his life, and largely involve Patrick engaging in Avengers-style combat with druids and demons.) In another sense, however, we know Patrick much better than most people from this period, because two texts actually authored by him have survived. One of these, his Confession, sketches out some brief details of his life. When Patrick was 16, Irish pirates raided his home, killed the household servants, and took Patrick himself captive. He was brought as a slave to Ireland, a place where he did not speak the language, where the religion of his family, Christianity, had only a tenuous toe-hold. He labored as a slave for six years before finally managing to escape back to Britain, where he was he reunited with his family and ordained a priest.

Several years later, however—against the wishes of his parents, and possibly against the orders of his religious superiors—he decided to return to Ireland permanently as a missionary, after dreaming that he heard the residents of the place where he had been enslaved calling out to him for help. In his writings, he described himself a profuga—a fugitive or, if you like, a refugee—and as a servus, a slave, of the Irish people.

There is something rather striking about having a cultural figurehead who was once a foreign-born slave. Patrick’s identity fits, not too terribly, into the Irish-American immigration narrative, and the idea of making a home among inhospitable people: but it’s a curious complication that the Irish, in Patrick’s story, were the ones doing the enslaving. Of course, Patrick’s enslavement isn’t the primary feature of his public image in America. It might be a good thing if it were. If cultural communities insist on having historical patrons, selecting a person persecuted by some past version of your community seems a healthy choice. That way, when if you are a suffering member of the community, you can look to that person’s suffering; and if you are prospering, you can look to that person’s persecutors, and see if you find any troubling family resemblances.

Given Patrick’s background, it seems thematically appropriate that one of the places where St. Patrick’s Day is celebrated today is Montserrat, a small island in the Caribbean where 88 percent of the population are the descendants of African slaves. Many Montserratians bear Irish-sounding surnames, like Lee, Ryan, Meade, Daley, and Sweeney. With lots of drinking and wearing-of-the-green, their St. Patrick’s Day bash resembles other such celebrations the world over—but the purpose of the holiday here is slightly different than elsewhere, in that it commemorates not just St. Patrick himself, but also a slave uprising that took place on Montserrat on March 17, 1786.

How did 18th-century Caribbean slaves come to choose St. Patrick’s Day as the ideal date for a rebellion? We are many centuries after Patrick’s time, and Ireland is now under English rule. Many Irish have begun striking out for the New World, some as entrepreneurs, others as indentured servants. Among Montserrat’s earliest European inhabitants were Irish Catholics who had been expelled from the English settlements in Virginia and on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts, due to religious tensions. Montserrat, like Ireland, was an island with a tumultuous history of conquest: Its previous inhabitants had been driven off by the Caribs, who were in turn displaced by the Europeans. By the 17th century, the title to the island was owned by an English lord, who soon leased his proprietary rights to colonial governors, whose job it was to extract value from the land.

There was a sharp social division between Montserrat’s predominately Irish laboring class and the English and Anglo-Irish planters who governed the island. Still more Irish arrived in Montserrat starting in 1649, when the armies of Oliver Cromwell, then Lord Protector of England, defeated the rebelling Irish Catholic gentry, and the English government began deporting political prisoners to the Caribbean. Other Irish criminals and so-called “sturdy beggars” were transported to the island, too, as a penal measure. Unlike other Irish bonded laborers, who “voluntarily” sold their freedom for a period of years, these deportees were sent to the New World against their will. On arrival, the prisoners’ labor was purchased for a specific period of time, usually for 10 to 12 years. Though this term of indenture was long, it was, at the very least, finite. The same could not be said for the African chattel slaves who began to be imported around the same time. They had virtually no hope of earning or waiting out their freedom.

By the 1650s, a hierarchy had coalesced on Montserrat of Anglo-Irish planter elites, predominately Irish Catholic indentured servants, and African slaves. Montserratian historian Howard Fergus speculates that—at least at the very beginning—there may have been some degree of solidarity between the Irish indentured servants and the African slaves. Though a small number of the Irish laborers, after their indenture, came to own one or two slaves, the majority could not afford to do so; when the free Irish had any land at all, it was usually a small plot on desiccated land. Unlike in other British colonies, where housing arrangements were more segregated, poor whites and African slaves in Montserrat lived close together, sometimes even within the same homes. Evidently, the ruling class was anxious about where this proximity might lead, because in 1672 they passed a law forbidding free and bonded whites from conspiring with slaves to run away, and in 1680 banned blacks and whites from federating together in “convivial organizations.” Laws forbidding blacks from participating in most forms of economic activity—which benefited poor whites by reducing competition in their small-scale business endeavors—drove the racialized wedge even deeper. Later laws would allow poor whites to shoot on sight any black person attempting to steal their property.

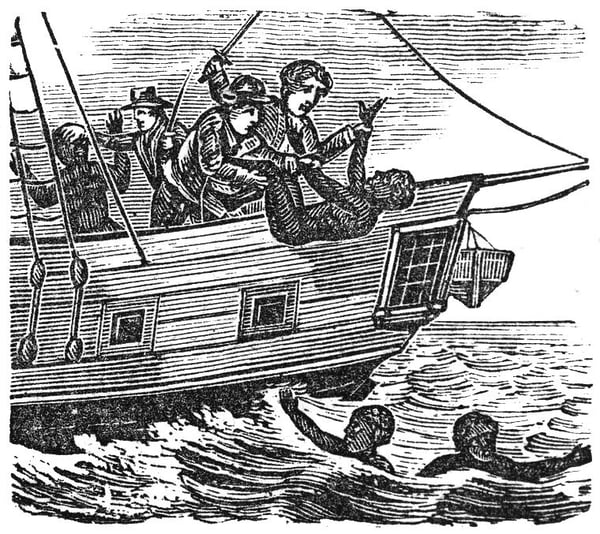

Life for indentured laborers in the Caribbean sugar plantations was incredibly difficult. While bonded, a person’s labor could be freely bought and sold, meaning that servants had no say in where they were to live or what kind of work they would be forced to do. In Barbados, Irish Catholics who came to the island as family units were reportedly split up and sold to different masters. Punishments for attempted escape were harsh. Howard Fergus records, for example, that several Irish women who tried to leave Montserrat in a canoe were sentenced to 39 lashes on their bare backs, and were then ordered to be sold for an additional four years past the completion of their original period of indenture. Nevertheless, by any objective measure, the African slaves in the Caribbean suffered far worse. Punishments like drawing and quartering, typically reserved for high crimes like treason, were meted out to slaves for simple theft; lesser punishments included mutilations and repeated brandings with hot irons. Starting in 1696, any slave caught stealing equipment in Montserrat valued at 12 pence or greater was sentenced to death, while a slave stealing any item of lesser value was to be whipped and have both ears cut off. At every point, the law emphasized that slaves were property, not persons—and in some cases, not even property of any particular value. A slave who murdered another slave, for example, was merely fined, whereas slaves who destroyed non-human property were tortured and killed.

Over the next century and a half, the Irish population on Montserrat dwindled, as most Irish servants who completed their indenture found little possibility for upward mobility on the island, and chose to leave where they could. Slaves had no such option. In 1768, a number of slaves planned an attack on the seat of colonial government in Montserrat on the feast of St. Patrick, a day when the inhabitants of the island typically gathered. The rebellion was brutally suppressed, with nine ringleaders executed and 30 others banished, probably to other colonies. It was to commemorate this attempted uprising, about which few concrete details are known, that the Montserratian St Patrick’s day celebration was instituted in the 1960s. It also soon came to be marketed as a tourist attraction, emphasizing the island’s historical Irish connection.

Howard Fergus—himself a black Montserratian—regards with uneasiness this strange conflation of slave rebellion and Irish identity, given that the Irish indentured servants had been a transient class during a discrete point in the island’s history, and there was certainly no evidence that any Irish had ever assisted the African slaves in their bid for freedom. “The idea of a black Irish enclave in a distant tropical island or, another Emerald Isle with an Irish diaspora, sounds exotic and has prosperous possibilities for tourism,” wrote Fergus, “but has no strong support from the historical evidence available to us.” The Irish, in fact, left little mark on the demographics of the island: The island’s many Irish surnames are an inheritance of slavery, courtesy of Anglo-Irish and smaller Irish Catholic slaveholders.

One of the most disturbing aspects of the “Irish slaves” memes mentioned earlier is that they don’t merely try to present bonded labor and criminal transportation as horrific institutions in their own right. There would be little to contest there: The fact that many poor people, political exiles, criminals, and social misfits suffered in the course of their indentures, that many of them had their indentures forced upon them, and that some died before they could secure their freedom, is a human tragedy. But the proponents of the “Irish slave” meme, of course, are not merely seeking to draw attention to a lesser-known historical injustice: They seek to attack historically-marginalized groups by suggesting that since Irish people have recovered from the generational after-effects of their “slavery,” everyone else should have, too.

Of course, the architects of the Irish slavery pseudohistory were certainly aware that the sufferings of the Irish laborers, though real, simply didn’t register very dramatically against the gruesome backdrop of African chattel slavery (especially given the uncomfortable reality that some Irish people became slaveholders themselves). In order to substantiate their vision of the Irish as not just exploited, but unusually persecuted, the makers of these memes frequently appropriate stories of atrocities suffered by African slaves and attribute them to Irish bond laborers. Liam Hogan has collected memes that reference the dumping of 132 Irish slaves into the sea as a cost-saving measure, and has shown how this false account is directly lifted from the real-life Zong massacre, when 132 African slaves were ejected from a slave-ship in precisely this manner. Stories of Irish slaves being burned and beheaded, too, are borrowed directly from accounts of the sadistic punishments suffered by African slaves in the Caribbean.

In fact, the Irish were a diverse group in the Caribbean. Some were indentured servants. Some, especially the “Anglo-Irish,” were elites. Others were small-scale slave-owners. And Irish slave-owners could be cruel to their slaves. In an account of a trip to Barbados in 1654, a French priest named Antoine Biet wrote of visiting an Irish slave-owner (of unknown religious and social background) who had kept one of his slaves in irons for seven days for stealing a pig. Later, he cut off the slave’s ear and forced him to eat it. “He wanted to do the same to the other ear, and the nose as well,” wrote Father Biet, “I interceded on behalf of this poor unfortunate.” Though Biet was no egalitarian, believing that a firm hand was necessary “to keep these kinds of people obedient,” he was nevertheless horrified by what he witnessed. “These poor unhappy people tremble when they speak,“ he wrote, “and for my part, I assess the conditions of our galley slaves, who are condemned for their crimes, as being better than that of these poor unfortunates.”

Perhaps it’s too much to expect that Irish people in the Caribbean, particularly those Irish who did actually suffer heavily under indenture, would have had the wherewithal to empathize with the sufferings of African slaves. We may feel that we are too distant from the lived reality of their circumstances to assess whether we ourselves would have behaved more morally. But what about middle-class people of Irish descent, living in the United States during the height of antebellum slavery? Given economic and social breathing-space, did their identity as Irish people—many of whom understood themselves to have come to the United States to escape oppression—give them any special sympathy for the plight of slaves?

There was, in fact, a brief period in the 19th century when there existed a transatlantic alliance between abolitionists seeking an to end to slavery in the United States, and Irish reformers campaigning for greater political freedom. This alliance was chiefly embodied by the person of Daniel O’Connell, a hugely popular Irish Catholic politician dubbed “The Liberator.” An astonishingly talented orator whose so-called “monster meetings” drew crowds of tens of thousands, O’Connell had won a hard-fought legislative struggle in the 1830s to undo the laws that had barred Catholics from sitting in Parliament. By the 1840s, O’Connell had turned his sights on a new political goal: the repeal of the political union between Britain and Ireland.

Daniel O’Connell, in addition to his domestic political concerns, was also a vocal and convicted abolitionist. In this age when we are accustomed to politicians either being single-issue advocates, or otherwise having a lukewarm slate of broad policy positions, O’Connell’s ability to genuinely care about more than one thing at the same time feels refreshingly novel. O’Connell was a passionate advocate for abolition, even though it didn’t really benefit his campaign for Irish political rights in any clear way, and indeed, if anything, tended to complicate his efforts to seek allies and funding in the United States. O’Connell was fond of saying that he would never set foot on American soil until slavery was abolished. Upon meeting any American in Ireland, O’Connell would ask first if he owned any slaves, and then, if he said that he did, would turn his back and refuse to speak to him. He spoke of his wish that “some black O’Connell” would arise in the United States and urge his countrymen to “Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!” O’Connell’s rhetoric against slave-owners was fierce: In one representative speech, he declared that senator Henry Clay “ought to be drowned in the tears of the mothers of negro children.” (Can you imagine Bernie Sanders telling Jeff Sessions that he ought to be drowned in the tears of refugee mothers? These are cowardly times.)

Irish abolitionist societies, working in tandem with American abolitionists—including John Remond, a free black abolitionist who travelled through Ireland in 1841 to speak about the evils of slavery—put together an address to Irish emigrants in the United States, signed by Daniel O’Connell and 60,000 other Irish supporters. “We call upon you to UNITE WITH THE ABOLITIONISTS, and never to cease your efforts until perfect liberty be granted to every one of [America’s] inhabitants, the black man as well as the white man,” the address ran. “We are told that you [Irish Americans] possess great power, both moral and political, in America. We entreat you to exercise that power and that influence for the sake of humanity. … Irishmen and Irishwomen! treat the colored people as your equals, as brethren. By all your memories of Ireland, continue to love liberty —hate slavery—CLING BY THE ABOLITIONISTS—and in America you will do honor to the name of Ireland.”

The address, which was read out at Fanueil Hall in 1842, was supposedly warmly received by its largely working-class Irish audience. But in the weeks after the publication of the address, it soon became apparent that the broader mass of Irish Americans—especially the leaders of the Irish American political organizations that supported Daniel O’Connell’s bid for repeal of the British Union—were not interested in “clinging by the abolitionists.” Bishop Hughes, the highest-ranking Irish American in the Catholic hierarchy, openly opined that Daniel O’Connell’s signature on the address must be a forgery. The Irish American press decried the address’s attempt to appeal to a specifically Irish conscience, vigorously asserting that the Irish in America were actuated by loyalty to their adopted country over and above any loyalty to their homeland. The Boston Catholic Diary announced that Irish Americans would “acknowledge no dictation from a foreign source.” Most Repeal organizations in both the North and the South—deploying the popular gradualist argument that the over-hasty abolition of slavery would be the destruction of the American Union, and would thus cause more evils than it solved—rejected O’Connell’s appeal to unite the Irish cause with that of abolition.

O’Connell’s written response to one Irish American repeal society in Cincinnati castigated Irish Americans for their failure to rally behind abolition. “It was not in Ireland you learned this cruelty,” he wrote. “It is, to be sure, afflicting and heart-rending to us to think that so many of the Irish in America should be so degenerate as to be among the worst enemies of the people of color.” He called again on the Irish Americans to advocate for freedom, education, and full political rights for black Americans, and to repudiate the “filthy aristocracy of the skin.” “Recollect,” he wrote, “that it reflects dishonour not only upon you but upon the land of your birth. There is but one way of effacing such disgrace, and that is by becoming the most kindly towards the colored population, and the most energetic in working out in detail, as well as in general principle, the amelioration of the state of the miserable Bondsmen.”

In Ireland itself, indeed, there was broad support for the abolition of slavery. When Frederick Douglass made a lecture-tour of Ireland in 1845, he was disturbed by the extremity of the poverty he witnessed in various parts of the country, but simultaneously struck by the apparent lack of racism in all the people he met. “The warm and generous co-operations extended to me by the friends of my despised race,” he wrote to a friend, “the prompt and liberal manner with which the press has rendered me its aid—the glorious enthusiasm with which thousands have flocked to hear the cruel wrongs of my downtrodden and long-enslaved fellow-countrymen portrayed… and the entire absence of everything that looked like prejudice against me, on account of the colour of my skin—contrasted so strongly with my long and bitter experience in the United States, that I look with wonder and amazement on the transition.” He was thrilled to see Daniel O’Connell speak, and later told an abolitionist gathering how, as a boy, “the poor trampled slave of Carolina” had heard O’Connell’s name, and his call for a black leader to agitate among the slaves, “with joy and hope.”

Ultimately, nothing much came practically of the attempted alliance between the abolitionists and those seeking political independence in Ireland, as O’Connell’s health waned, and as more narrowly nationalist leaders (who declared that Ireland had “no Quixotic mission to hunt out and quarrel for (without being able to redress) distant wrongs, when her own sufferings and thralldom require every exertion and every alliance”) increasingly came to the fore of Irish politics. O’Connell’s abolitionism—together with his controversial assertion that Ireland would support England over the United States in order to prevent the annexation of Texas—sounded the death-knell for the repeal organizations that had supported his cause in the United States. In Ireland, meanwhile, public attention to the cause of abolition proved transient, especially as the potato blight took hold of the Irish countryside after 1846.

And in truth, Ireland’s commitment to abolition had never been pure. Irish agriculture had benefitted economically as a supplier of goods to the British West Indies, both in the time of slavery and under the subsequent racist system of “apprenticeship.” O’Connell himself, for all that he railed against slavery, had been reluctant to turn down subscription funds from the repeal organizations of the American South. And yet, there is a deep and undeniable appeal in the idea of a young Frederick Douglass drawing inspiration from O’Connell’s call for a black Liberator. It’s enough to make us wish that the ideal of oppressed Irish and enslaved Africans coming together under a common banner of freedom could actually have been properly realized.

We may feel, with some justice, that personifying whole nations is absurd, and that deriving a sense of identity from one’s ancestral antecedents is something we ought to be moving away from. That said, people best understand history through narrative, and so telling stories may be the best means of disrupting these stereotyped notions of culture and nationality—or at least beginning to refine them down to something truer and more nuanced. Of course, white supremacists seeding memes are not ingenuously looking to find historical truth; they’re just looking to spread propaganda. But for Irish Americans who feel a genuine connection with an Irish heritage, it’s possible that accurate presentations of Irish history can be a tool for disrupting unhelpful and simplistic assumptions. To the extent that Irish and Irish-American people suffered in the past, this should help inculcate empathy for all suffering people in the world today; and to the extent that Irish and Irish-American people inflicted suffering, or chose to ignore it, this should inspire self-criticism. It’s unfortunate, for example, that the hitherto little-told story of indentured servitude—which could be easily compared to many forms of modern wage slavery the world over, or the plight of people forced into unwilling migration by economic and political forces—is now a form of oppression that must be qualified and diminished, because badly-intentioned political actors have appropriated it as an excuse to disregard the even worse suffering of chattel slaves.

The story of the Irish in the Americas, in turn, illustrates some of the difficulty of trying to get groups of people with a shared experience of suffering—even if of different types and degrees—to see each other as allies. The left has not come up with a good strategy for combatting the divide-and-conquer strategies that elites used against the poor since the dawn of time. How do you get people to unite with those who are in the same or an even worse position than themselves, rather than trying to ally themselves with the oppressors that some part of them secretly desires to emulate? This is where race is especially pernicious, because whiteness allowed ambitious Irish to vanish into the broader mass of privileged people, while oppressed people of color had no such option. That said, it’s also true that many poor people in the U.S. today likely do have ancestral roots with the poor Irish of the past—whether these were the Scotch-Irish of Appalachia, or the Irish Catholic famine refugees. These Irish Americans are not the descendants of slaves, and their continued poverty has far less to do with systemized racial prejudice than with cruel economic policies that fall most heavily on people who are already poor. Nonetheless, their suffering is real.

How can the left, today, create a narrative that tries to show that poor whites, poor blacks, poor immigrants, have shared experiences of suffering, and common needs that are unaddressed by existing policy? The acute sufferings of some Irish and of all Africans in the Caribbean was one that produced no real solidarity. The same was likely true in the riot-plagued slums of 19th-century America, where poor white and black laborers struggled for self-sufficiency and some sense of dignity. But the indifference and jealous self-interest of the middle-class Irish in America, with reference to the question of abolition in the 1840s, shows that success and comfort can produce its own, even more morally hideous brand of complacency and cruelty. Perhaps we can still derive hope from the fact that the words of an Irishman, Daniel O’Connell, gave courage to Frederick Douglass.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation, purchasing a subscription, or supporting our podcast on Patreon. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.