How Big Pharma Makes a Killing From Letting People Die

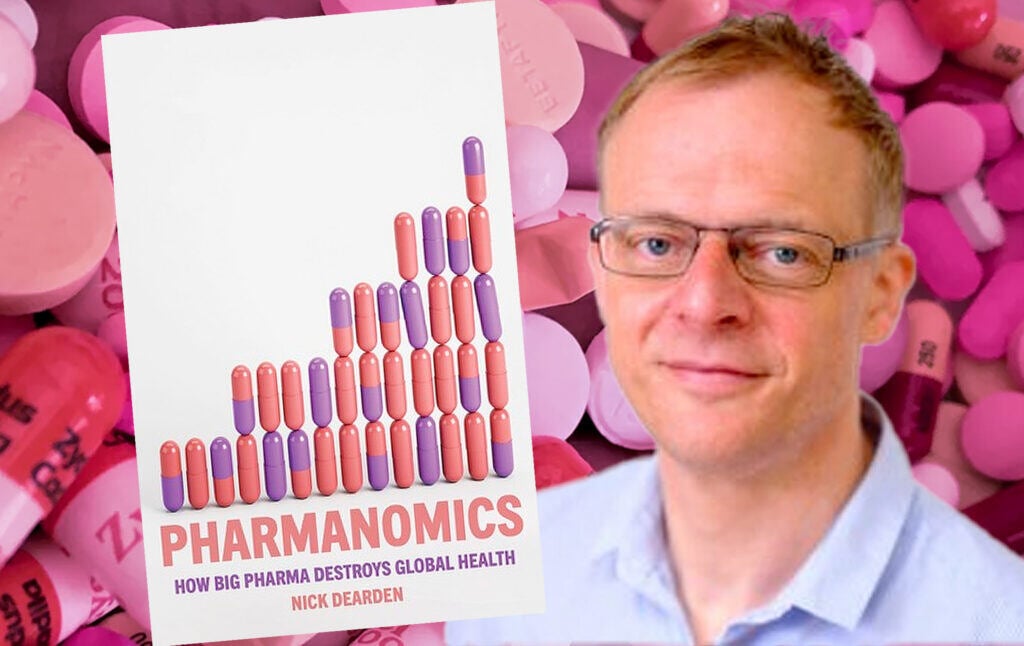

Journalist Nick Dearden on the basics of “pharmanomics.”

Nick Dearden’s Pharmanomics is an essential primer on how the pharmaceutical industry works, taking a tour across the globe to explain clearly why Big Pharma’s profits come at the expense of public health. Dearden, an investigative journalist and director of Global Justice Now, destroys the argument that high drug prices are necessary in order to maintain innovation. He shows how the pharmaceutical industry has pushed drugs that don’t work, buried harmful side effects, experimented on the Global South, and extorted the public to line its pockets. He explains why scientific research needs to be under public, rather than private control, and offers a vision for a healthcare system that actually takes care of people’s health. Dearden shows how the infamous Martin Shkreli, who became notorious for hiking drug prices, was not a mere bad apple, but following standard operating procedure in the world of “pharmanomics.”

Nathan J. Robinson

Your book goes through many different issues with pharmaceutical companies. To think about where we might enter this conversation, I thought we could begin, as you do in the book, with a microcosm: one of the examples that’s touted as a “bad apple” that made the news is the infamous Martin Shkreli. You bring us back to that story as a kind of case study in something that we can all obviously understand as a predatory and wrong way to deliver medication to people. Could you remind us of the facts of what happened there?

Nick Dearden

Of course. His background was in finance; he came from a hedge fund, and he said, by his own admission, he moved because there wasn’t enough money to be made in hedge funds for him and thought Big Pharma was a more profitable way to go. He was absolutely right. What he did essentially was look around for drugs that there were coming to the end of their patents—so that means the drugs that he was looking at still had monopoly rights applied to them. He figured, I got a little bit of time left before other generic companies can come in and make these drugs and the price falls massively, so I’ll buy them up and then jack the price up by hundreds or thousands of percent overnight, and that will make me a nice income stream for the time remaining before anyone else can make these things.

The most famous case was he bought this drug out that is extremely useful at fighting cancer and infections, particularly for people who are HIV positive, and he jacked the price up several thousand percent overnight. And I think the incredible thing about Shkreli is he does it all with a smile on his face.

Robinson

A smirk, I think, is more like it.

Dearden

So, he kind of brags about it, and he says, this is how the industry and how capitalism works; therefore, I’m not some evil guy. I’m actually playing by the rules of this system, and I’m doing it extremely well. He’s exactly right, and he takes it to an extreme. He enjoys playing the role of a pantomime villain. But beyond all of that, there’s something right about what he says. And of course, that’s why the rest of the pharma industry hates him, not because of what he’s done, but because he exposes this deep truth about the way that they actually operate.

Robinson

What I think is interesting is you cite his case as an example, and you quote him saying, “My shareholders expect me to make the most profit, not half or 70%, but 100% of the possible profit. This is a capitalist society, capitalist system, capitalist rules.” And he said, “The other pharmaceutical companies might like to pretend they’re in a different category,” but, he said, “they don’t have any higher moral ground to comment on what we do.”

I take it that your point in the book is he’s kind of right about that because that’s true. It is the way the industry works. He is not a “bad apple.” The smirk is the only thing that distinguishes him from the rest of the industry.

So, maybe we could dive into that a little more. The thing that he did then, which was gaining control of intellectual property—a state enforced monopoly over some set of knowledge—and then using that to extort as much money as possible, as you point out, is an extremely common way to make money.

Dearden

Yes, it’s really common. The big takeaway for me for this research was, we think this industry basically invents drugs that deal with awful diseases and then profiteers off them. We assume that’s how the industry works. And the industry likes to tell us, you might not like us and the amount of money we make, but essentially, at the end of the day, without us there are no medicines.

What I discovered is that is completely untrue. They don’t, by and large, invent medicines. They behave like hedge funds; they buy the rights to produce medicines that have been made by others, with public money or small biotech companies, and then they squeeze the most they possibly can out of those drugs, whatever the consequences for society and how unaffordable they are. So actually, the way Shkreli has behaved is no different from the way that AbbVie has behaved when it comes to drugs like Humira, invented by someone else.

Robinson

Tell us a little bit more about that.

Dearden

This is a very useful drug if you’ve got Crohn’s disease or rheumatoid arthritis. It’s a kind of anti-inflammatory. This drug was created on the back of massive amounts of research going back many years, and brought to development by a company that AbbVie then buys up. So, AbbVie had nothing to do with inventing this drug at all—they bought up the rights to the drug. They then spent a bit of money that they claim was improving it, but all the evidence points to the fact that far from improving the drug, nothing was made better about the drug in terms of the patient’s experience of it.

Essentially, what we think that development was about was to make small so-called innovations that will actually allow them to extend the patents even beyond what they were already given, just these very small changes called “evergreening,” and then they can apply for new patents on it and jack up the price. They turned Humira into the most expensive drug in the world. I think we’re talking about just below $100,000 per patient course for this drug.

So, a phenomenal amount of money. Even in my country, where most of our drugs are paid for by the National Health Service [NHS], this wasn’t available because it was just too expensive. When it was available, it was rationed. In the US, it is only the very richest people who could possibly afford to get this drug. What has his company done other than made a lot of money off this drug?

Robinson

You mentioned the National Health Service. I think some people might assume that because you have publicly provided healthcare, that the National Health Service could force down a lot of the prices on the these things and keep them under control. So, why doesn’t that happen?

Dearden

To some degree, it can. The National Health Service pays far less for our medicines than you do in the US because we do have the ability to negotiate. But sometimes the companies just will not play ball. They want it to be provided by the NHS because, of course, they’re going to make some sales off that, but not if it fundamentally damages the price that they’re able to charge in the US. So, there are times they simply won’t negotiate on them. Eventually, we got there, although it still cost an awful lot of money, but I think it’s a really good point you make because I think the problem here is that the industry has actually become unsustainable now. The amount they are trying to get for these new drugs is so astronomical, that even single-payer systems, like we have in large parts of Europe, are struggling to afford the prices that they can negotiate with these companies.

Robinson

I want to go back to what, I think, is the core point. You go through some of the history, and you point out this is not, in fact, a new phenomenon that these pharmaceutical companies have become more financialized and more like hedge funds over time. You point out that half a century ago there were hearings about predatory pricing by drug companies, and the story in response is always the same talking point: the prices are high because the research is expensive; if you do anything to regulate the prices, you are going to kill innovation and research. You heard that half a century ago, you hear that today from Bill Gates—it’s always the same point. So, I feel like addressing this point is so crucial to exploding basically the only myth they have because they repeat it over and over and over.

Dearden

It absolutely is. And the fact that we kind of all believe that to one extent or another is because that myth was created by the pharmaceutical industry to avoid regulation. There was this moment, like you say, in the kind of 1960s where in the US, the UK, and elsewhere, the pharma industry as we know kind of emerged after the Second World War. They became enormous giants on the back of a whole bunch of blockbuster drugs like antibiotics, steroids, vitamin supplements, tranquilizers—all these drugs that we hadn’t had before. They kind of changed the way we as citizens, we as people, relate to medicines, and this made them phenomenally profitable. But it also drew a lot of attention to what was going on here.

And so, there were Senate hearings, and hearings in the UK Parliament, to say, actually, we’ve got to control this industry because it’s quite central to our lives. Big Pharma, of course, didn’t want that because they wanted to make as much profit as possible. And so, they created this myth that we still talk about today. The problem is that the myth became less and less true as time has gone by. There was some case to be made in the 1960s that they did actually create drugs. Like everything in science, it is still based on generations of previous scientific knowledge that you would think you shouldn’t really be able to monopolize.

But nonetheless, they did actually produce some stuff. In the most infamous case, Purdue Pharma produced Oxycontin and then were utterly egregious in the way that they marketed that drug to people. It was their drug, if you like, whereas nowadays, the idea holds no water whatsoever because the drugs that they are profiting so handsomely off they haven’t even created. And yet, this myth is still there. They’re the goose that lays the golden egg for the economy, they are important to us and our individual health care—heaven forbid we do anything whatsoever to constrain their behavior.

Robinson

As you point out, it is not only that they have stopped laying golden eggs—that is to say, innovating new life-saving medicines—but you point out a number of ways that these terrible incentives actually make global health worse and prevent us from discoveries that we might achieve if we didn’t have profit seeking institutions with bad incentives.

Dearden

Completely. It discouraged and disincentivized them from actually creating important medicines. You can see it with antibiotics. Antibiotics, we know, are beginning to lose their effect. This is a major problem for humanity. Our entire medical knowledge depends upon having antibiotics. You could die of simple cuts on your finger if you were to get infected in previous ages before antibiotics—cesarean sections or certain cancer treatments all rely on antibiotics. We need to discover new antibiotics, and the pharma industry is investing nothing in this research at all. There are no incentives in it to do that because any new antibiotics that they create today will be second generation and used very sparingly. They’re going to be used when our current antibiotics fail in patients. They simply reason there’s not enough profit to be made in holding such a drug: by the time we will make any serious profits, our patents will all be expired. So, there’s no incentive to deal with a kind of health issue of epidemic proportions, and so they’re just not doing it. The incentives built into the system are, like you say, actively preventing them doing the job that they’re supposed to be doing, and we assume that they’re doing.

Robinson

I think you point out the vaccine research is another area that is massively underdone because it’s not the most profitable.

Dearden

It’s not at all. So, you look into the possible pathogens that cause a pandemic. It might not happen, so you could be sitting on a bunch of research here or a bunch of intellectual property that’s making you nothing at all because it might not happen. So, going into COVID, the industry has done almost nothing. The World Health Organization said years ago, there’s these 16 pathogens that could cause a pandemic, and yet, we are alarmed to see that almost no research is being done by Big Pharma into these areas. There’s some research that has been done, but it’s being funded by the NIH and done at universities and by public researchers and so on. And they were absolutely right. COVID hits, and the pharma industry has gotten nothing. Fortunately, thanks to public money, we have got some information on how these viruses work and how we might be able to deal with them. The problem is, to develop that, we simply handed over that research to Big Pharma, and they were able to monopolize the vaccines that came out of it and decide who got them and who didn’t—essentially, who got to live and who got to die. That was placed in the hands of pharmaceutical executives, who’ve done almost nothing to research these vaccines in the first place, and some of them became billionaires out of that. The result for the rest of the world was a massively inequitable distribution of those vaccines around the world and an artificial limit placed on how many we could make.

Robinson

As we look back over the COVID pandemic, could you go into a little more detail about just how grotesquely unfair the resulting distribution of both vaccines and profits was out of that?

Dearden

Absolutely. So, you’ve got the two companies who sit on the kind of gold standard mRNA research for COVID vaccines: Pfizer and Moderna. At the end of the first year of those vaccines being proved to be effective, virtually all of their sales had gone to the richest countries in the world, and nobody else. Nobody else really had anything because they were simply signing contracts with the most powerful government leaders. That was where they expected to be able to make their money, and they wouldn’t share the technology with anybody else. And it worked for them. It didn’t work for the billions of people who didn’t have access to their vaccines, but it worked for the pharma executives.

The head of Moderna and several members of its board became multibillionaires. This was the only product they had on the market, and all the sales were massive sales to a handful of governments. So, this is easy: you’re not desperately trying to persuade people to get your product—you have a captive market—and they become multibillionaires off the back of it. Pfizer, in the first year of its COVID vaccine coming out, made $36 billion in sales. In the second year, Pfizer added an antiviral, and those two drugs alone made it $50 billion. It’s the most money any company has made from one or two drugs in a single year, in history. Vast. And yet, who could get these was restricted to a tiny fraction of humanity. By and large, the only Pfizer vaccines that were given in the majority of the world only got them because the US donated a fair amount of its doses. Otherwise, they would have had none.

Robinson

Just to drive this point home, it’s fair to say that there are plenty of people who are not alive today who would have been alive if we’d had more equitable distribution.

Dearden

That’s exactly right. We know the vaccines were effective in preventing people from dying. People still got COVID, but we know that the suffering and the likelihood of death was reduced. And so, even in this really extreme situation—we’re being locked down around the world and people are dying in phenomenal numbers—Pfizer and Moderna held on to their intellectual property and refused to share it with the many laboratories and factories around the world that could have created more of these things. And even if they had done that, let’s be clear, they would still have made all the money they made.

And I think this goes to the heart of the problem. The problem is that they make their money and believe—and they’re right, to a degree, in the monopolization and control of a technology—the worst thing you can do is share that. The money is not coming so much from the fact that you’re selling plenty of doses, pills, or whatever, it comes from the fact that you control and monopolize that knowledge. You enclose it; you place a wall around it and prevent others from getting it. That’s what makes it valuable to you, and that’s key to the problem that we saw in COVID. It was that precise monopolization that was preventing the many other factories and countries that could have been producing from producing it. They would have still been rich, but not rich enough. It goes back to Shkreli’s point: it’s not about making my shareholders rich, it’s about making them as rich as we can.

Robinson

I can’t remember if this comes up in your book, but I feel like in the United States, especially, there is now a lot of suspicion of Big Pharma. They’ve almost, through tarnishing their reputation, encouraged conspiracy theories to flourish that make people not want to take vaccines. They think, the companies that make these are just trying to make as much money as possible. I don’t trust a word they say; I don’t trust them to not lie to me about whether these things are safe. Therefore, I’m not going anywhere near that. Having the profit motive in the health system hurts, but almost rationally, people come to distrust things that they’re being told because they don’t know if those things are true.

Dearden

I think that’s exactly right. They’re almost encouraging the proliferation of conspiracy theories by the fact that they’re so untrustworthy. You can see this all over the world actually, and I looked at one case in one part of Nigeria where there was an outbreak of meningitis in, I think, the late ’90s. The pharma company rushes in thinking this is brilliant because we may have a new drug that deals with this, let’s test it out. They behaved in an unbelievably unethical way—the kind of way that would have never been allowed in the West, where they realized there were patients it wasn’t working for and then didn’t transfer them onto a kind of older medicine. And in that part of Nigeria, to this day, there is just immense suspicion of Western medicine. People just don’t want it, and it’s not surprising, really. For those of us who kind of think it’s a good thing that you take vaccines for diseases, it makes our job harder.

And what I say to people is, you don’t need to come up with any conspiracy theories, you just need to look at how these companies openly act, and that explains the fact that they’re entirely driven by shareholder maximization. But it doesn’t mean you need to distrust the science. What we actually want to do is liberate that science from the grasp of these corporations so that they’re no longer making these astronomical profits and denying many people around the world medicines that could help them. I completely agree, in some ways, you’re fighting a losing battle because they’re so untrustworthy as corporations.

Robinson

It’s kind of like how the Tuskegee experiment here sort of destroyed confidence among African Americans in the public health system because they were lied to. You document all sorts of examples of this—you mentioned one example there of foisting expired and dangerous medicines on the Global South, and various kinds of experiments and tests that don’t reach the standards that will be applied in the West. This is really rotten treatment of people in the Global South as if they are less valuable people.

Dearden

Absolutely. It’s quite expensive to dispose of medicines that have gone past their date. You can’t just throw them in the bin; you have to go through a process of disposing of them safely. But, to get a tax rebate, the companies would claim that these things were donations and just send them somewhere else, like to an emergency situation, and they wouldn’t have to dispose of them safely. It was basically a way of saving money, and you’d end up with all sorts of inappropriate stuff that people didn’t understand how to use, or would have no need for. The most extreme one being an appetite stimulant sent to a famine zone just to get rid of this stuff. Extraordinary stuff, and [it’s done] just to, at the end of the day, limit the money that you should be paying to get rid of stuff that’s going out of date safely. In COVID, it was the same thing, insofar as many people around the world were able to get vaccines—very often, they would be very close to their expiry date by the time that countries actually got them. And of course, that’s going to worry people in those countries and make them think, “I don’t want a vaccine that’s gone old.”

Robinson

Fair enough!

Dearden

Yes, fair enough. So, I’m not going to get vaccinated.

Robinson

There’s so much that is documented in your book, and we can’t get into all of it. But one of the issues that you mentioned earlier that I want to dwell on is these bad incentives. You mentioned marketing and the opiate epidemic here. Even when you have drugs that have a legitimate purpose, there is an incentive to encourage doctors to prescribe these inappropriately because it makes them a ton of money if they do that.

Dearden

Yes. Obviously, everybody in the US is very familiar with the opioid epidemic. An unbelievably strong painkiller was created that should have been extremely rationed in terms of who it was given to—this is end of life care. But they decided the way they’re going to make profit off this is not just by giving it to a very few people, but to absolutely everybody—even for moderate pain, you should be taking an Oxycontin. That was the idea they put into doctors’ heads and spent an awful lot of money convincing them to do that, and also creating research to suggest this wasn’t addictive, when any normal person would have been able to look at this drug and say, obviously, that’s going to be an extremely addictive drug because it’s not unlike heroin. You don’t need me to tell you that. I’m sure listeners and readers will know all about it, and you can watch Painkiller on Netflix to see how all of this happened. But really unhelpful incentives, to say the least, are built into the system. It doesn’t really matter what the cost is, in terms of people’s health care, and in terms of life and death. What matters is making money.

And again, I think Purdue were quite honest about that, which is one of the reasons it’s so fascinating. Arthur Sackler, the patriarch of the Sackler family, actually developed these marketing techniques selling Valium for Roche in the 1960s. He theorized the most effective way of doing this is to market to doctors because people trust their doctor. It’s more effective, as a company, to try to get ordinary citizens to buy this stuff. You’ve got a kind of almost corrupt people who the patients ultimately trust, and they did that to an incredible degree with Oxycontin.

Robinson

They made a lot of money. It goes back to that, and destroying trust in doctors because people are going to find out the truth.

Dearden

Of course. I don’t if you’ve seen the show, but they created these incredible little cuddly toys that were like Oxycontin pills with little arms and smiley faces and so on. It’s really, really incredible.

Sometimes those incentives will be to sell as many as possible in a completely inappropriate way. Sometimes it will be to sell hardly any, and that doesn’t matter, either, because what you’re doing then is turning medicine into a kind of luxury good, something that only the few can afford, and that’s how we’re going to make our money out of it. But in both cases, it’s a completely inappropriate way of dealing with that medicine, but the incentives built into the system encourage them to do that.

Robinson

And I suppose there are other examples of if a company is selling plenty of drugs, it has a strong incentive to conceal or downplay when it doesn’t work.

Dearden

Oh, yes. Hugely. And I think that’s the thing to remember about pharma, particularly in the US. This isn’t just a powerful industry, which has a lot of lobbying clout. It’s almost become integrated into the various systems that are meant to regulate it. It’s become integrated into the health professional system by corrupting doctors and so on. It’s become integral, by giving money to universities and setting up partnerships, to the way that research is actually carried out. It has an insidious relationship at all levels of society that impact on its operations. Someone described that as a pharmaceutical-industrial-complex, which is that it’s not simply going to be dealt with by restricting lobbying power. As much as that might be important in itself, you need to actually root out the kind of power that this industry has in all different levels of society.

Robinson

You have an incredible story in the book of the Canadian researcher who’s pursued by the pharmaceutical industry. It’s a remarkable and extreme case of what can happen if you try to dissent from this kind of integrated system where research is being corrupted.

Dearden

Yes, she’s Nancy Olivieri, and she still works in Toronto. It’s an incredible story where she’s a world expert in this very rare disease, and a company comes along and thinks it might have the answer to reducing the suffering of her patients, and she tries it out. It’s going well, at first, and she’s quite enthusiastic. But then she realizes there are some really very dangerous and worrying side effects. She goes to the company and reports this, and she says, I’m going to tell my patients who are on this trial about this because they have a right to know. And then she starts getting threatening phone calls and letters through the post—she’s told to shut up and not tell her patients; otherwise, they will take legal action. She gets dismissed from her job because she works at a university that the company is giving money to. She really gets hounded. Her life and career is really on the edge, and she has to fight like hell to get it back for doing what you would regard as the basics: for just telling you the truth about the stuff that you’re taking. The company actually tried to rush this drug out and said, we don’t really care what you found here, there’s money to be made, and we’re going to start producing this thing. She’s a great example of how that insidious power works throughout the world of research.

Robinson

Yes. That’s at its most extreme, but you document so many different instances that seem to come down to this same problem of the way that markets and the profit motive corrupt public health. To conclude, you make clear in the book that you’re not offering a bleak and pessimistic look entirely. You do think there are alternate ways of organizing the research, production, and distribution of necessary medicines. Can we do this differently?

Dearden

Absolutely. We really can, and I think it is a hopeful time. COVID has kind of woken people up to what’s gone wrong. For many governments in the world, they were really astonished because they’d been told, don’t worry about it. You don’t need your own production facilities and your own research and development, the market will provide. And when the market doesn’t provide, don’t worry, we’ll help you out with some philanthropy and with some charity. COVID hits, the market doesn’t provide, the market seizes up, and they can’t get hold of anything. And by the way, we’re not going to give you anything as a donation either. You’re on your own, essentially. And this wasn’t just very poor countries. This was reasonably rich, developing countries like South Africa and Brazil. And so, they have kind of woken up and are saying, if we want to be protected next time, we need our own manufacturing and our own research and development, and they’re beginning to do that. There’s a great example of a group that went to Moderna and Pfizer and said, we want to learn about mRNA so we can make vaccines, not just for COVID. We think it might be possible to make mRNA vaccines for TB, HIV, and certain types of cancer. But Moderna and Pfizer were not playing ball with that and said, you’re on your own. The group did it—they cracked a COVID vaccine quickly. They still need to work out how to actually go about producing that and getting it in people’s arms and so on, but they may even be on the verge of creating a vaccine for TB there. The really revolutionary thing about what they’re doing is they’re saying, we’re not going to monopolize this knowledge, and instead, we’re sharing it with countries around the world that have the ability to produce and work on it. They’re being collaborative. So, I think that’s really exciting. But I think even in the United States, there is a realization or recognition that what happened was simply not right. I quote some guys in the US administration who were trying to negotiate with Pfizer and Moderna during the pandemic, and they claimed Pfizer was trying to charge them $120 a dose. It came down in the end, but they said these guys are like war profiteers, and the incredible thing is they didn’t even invent the vaccine. There’s one guy from the administration quoted in the FT article saying, the greatest marketing coup in medical history is the fact we call this thing Pfizer’s vaccine. It’s not Pfizer’s vaccine, they didn’t even invent it. So there was a recognition that what happened there was completely and utterly out of control, given the amount of public money put into this stuff. And I think you’re seeing that in some of the policies enacted both at the federal level, but also at the state level. California is now saying, we’re just going to start to produce insulin at cost and get it out to people. We can’t deal with profiteering anymore because it’s having a detrimental impact of such scale on our society, that even in the country, which historically has been in lock with the market, has failed us.

Robinson

I think for more details on all the cases that we have discussed here today, our listeners and readers need to pick up the book Pharmanomics: How Big Pharma Destroys Global Health. But as I say, and as Nick has indicated there, he also lays out alternate possibilities that will not leave our health at the mercy of the free market forever. Could you tell our listeners about what you all do at Global Justice Now and about your organization?

Dearden

We believe, essentially, the problems of the world, in terms of poverty, inequality, climate change, are baked into the rules of the global economy. The global economy that we’ve seen developed over the last 30 or 40 years has had a really detrimental impact on many people’s lives, but has had a very positive impact on the lives of corporate CEOs and their shareholders. In fact, the economy was kind of built in their image. And like you say, many of the rules that govern how our economy works are maybe very good for the profits of the few, but have been a complete disaster for the lives of the vast majority around the world. We challenge those rules. So, when it comes to pharma, we’re challenging the intellectual property rules that give them this immense power to monopolize the knowledge that, we believe, is illegitimate, and they shouldn’t have. Similar rules exist that are fueling climate change and protecting the fossil fuel industry, and we campaign against those rules, too. It’s a big fight. You’re up against huge vested interests, but you can win. We’ve beaten trade deals and investment deals that would have made things worse, and we’re now beginning to unravel, I think, the economy that was put into place in the late 1990s, which has prevented countries and people and communities having control over their lives. We try and do that with an eye to not just our own society, but of course, to people around the world who also need the same rights as we’ve got, and want to live with decent health care and education and so on. So, we try and create a kind of international feeling and international spirit in the way that we create new policies and laws for the world.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth. Full conversation can be heard on the Current Affairs podcast.