All of Your Attempts to Redeem Martin Shkreli Will Fail

Writers are scrambling to explain why the detested pharmaceutical executive is Not As Bad As You Think. But he’s precisely as bad as you think. Possibly worse.

For some reason, recently a number of writers seem to have taken it upon themselves to salvage Martin Shkreli’s reputation. Previously, there had been a rough consensus that Shkreli, the oily, simpering pharmaceutical executive who raised the price of HIV drugs by 5000 percent before being indicted on fraud charges, was one of the most cretinous human beings alive. This seemed utterly uncontroversial, in fact so self-evident as to render debate unnecessary.

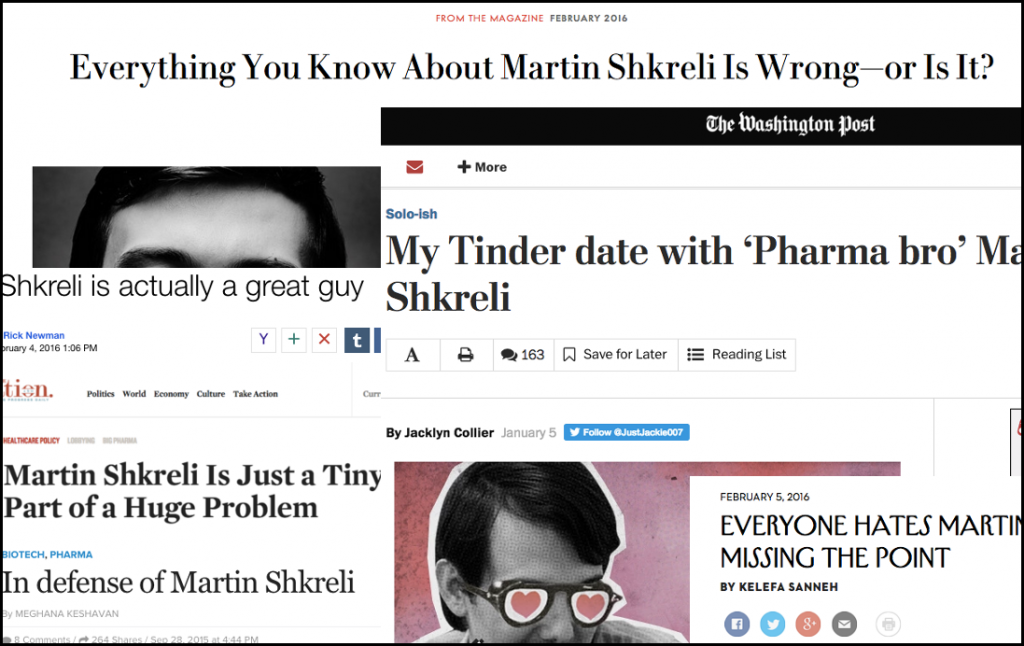

But a miniature genre of article has sprung up recently: the Martin Skhreli Is Not As Bad As You Think hot take. From Vanity Fair to The Washington Post to The New Yorker, authors have issued the provocative thesis that, far from being the mealy, smirking, patronizing little snot he appears to be both at a distance and up close, Shkreli is anything from a blameless cog in a vast dysfunctional apparatus to a sweet and tender do-gooder unfairly disparaged by a society too stupid and hateful to appreciate his genius.

The former type of portrayal is the least outlandish, though perhaps the more insidious. Some have conceded that while Shkreli might indeed be a greedy heartless reptilian AIDS profiteer, his behavior is enabled by a broken system of drug approval and pricing, and the public’s ire should be directed away from Shkreli and toward that system. James Surowiecki gave a typical example of this argument in The New Yorker:

The Turing scandal has shown just how vulnerable drug pricing is to exploitative, rent-seeking behavior. It’s fair enough to excoriate Martin Shkreli for greed and indifference. The real problem, however, is not the man but the system that has let him thrive.

The Atlantic‘s James Hamblin echoed this, saying that Shkreli’s existence is “a product, not a cause,” with an innovation-stifling regulatory structure far more to blame for Shkreli’s scheming.

The thrust of these arguments is easy to buy: by focusing on the acts of a single individual for his noxious personal qualities, instead of on the legal framework in which he operates, we entirely fail to advance any solution to the actual problem of drug price hikes. While it may be satisfying to hurl abuse at Shkreli, he is merely a scapegoat. Business Insider noted that Shkreli was “right” in insisting that he needed to maximize shareholder value, and went so far as to say that he may be “the villain we need to get our healthcare system in action.” One doctor mirrored Shkreli’s own insistence that because what he did was legal, it wasn’t wrong, saying:

Remember, he is not doing anything illegal. The media is portraying him as an unsentimental money maker. I couldn’t care less if he boiled his neighbor’s bunny. The demonization distracts us from the most important question, which is not why Shkreli is raising the price of Daraprim by 5,500 percent, but how.

But here is where I profoundly differ with these people: if Martin Shkreli boiled his neighbor’s bunny, I’d be disgusted, not indifferent. I mean that quite seriously: nobody should have attention deflected away from their harmful, immoral behavior simply because it occurs within the context of more pressing structural issues. What these arguments encourage us to do is to shift blame away from Shkreli and onto our laws and policies. But by treating individuals like Shkreli as mere inevitable consequences, rather than human beings who make deliberate choices for which they should be held morally accountable, they effectively exonerate heinous behavior.

It’s completely accurate, of course, to say that our time is better used trying to devise a fair drug market rather than sitting around despising Martin Shkreli. However, in apportioning blame for the Daraprim hike, Shkreli bears complete responsibility. It is no defense of anything to say that it is “legal” or made possible by the market. And if he believes that limiting patient access to medications is compelled by his mandate to maximize shareholder value, then Shkreli should find a job whose mandate does not require one to hurt people.

This is significant, because it reflects the way businessmen are often spoken of: as if they cannot be expected to act differently. Marxists are just as guilty of this as free-market libertarians; they believe it is senseless to “moralize” about the rich, who after all are the product of inevitable historical forces; to blame them is akin to blaming the moon for the tides. But I disagree strongly: I believe that humans have free will, and that it is both right and necessary to detest the world’s Shkrelis, because unless morally shameful behavior is treated with scorn, it no longer remains shameful. Those who willingly maximize profits at the expense of the sick, regardless of whether they are behaving predictably or legally, should experience intense public ire. “Don’t Hate Martin Shkreli, Hate the System That Made Him,” we are told. But nothing stops us from hating both; nobody is required to choose.

But beyond the “focus on the system” angle, there is another class of Shkreli-defense out there, one far more extreme in its propositions: the “Martin Shkreli is actually a good guy” defense. A number of articles actually attempt to make the case that Shkreli is decent, sensitive, and misunderstood.

The general thrust of these articles is that once you get to know him, Martin Shkreli turns out to be a more “complex” and human person than his irritating public persona would have us believe. “When speaking for himself, instead of battling crass media characterizations, Shkreli is an endearing chap,” said Yahoo Finance‘s Rick Newman, in an article entitled “Martin Shkreli is Actually A Great Guy.” Vanity Fair and Vice have both run humanizing profile stories based on lengthy interviews. The Vanity Fair profile contained the following lines:

He’s such a perfect villain when viewed from afar that it’s almost impossible not to like him more up close. He swerves seamlessly among obnoxious bravado, old-world politeness, purposeful displays of powerful intelligence, and even flashes of sweetness.

And the Vice profile, while questioning a number of Shkreli’s claims and containing numerous criticisms, calls Shkreli a “finance wunderkind” and “a Horatio Alger story” and sympathetically relays Shkreli’s claim that his unapologetically money-grubbing attitude is merely an exaggerated caricature that he plays for the public to entertain himself. The Vice reporter sees Shkreli as an enigma because:

On one hand, Shkreli can wax poetic, as he did to me, about the “puzzle of medicine” and his desire to help people. On the other hand, he told Vanity Fair that he switched to biotech because hedge funds weren’t lucrative enough.

Let’s be clear: these reporters are dupes. The behavior Shkreli displays, veering wildly between charm and amorality, is not a sign of complexity, but of sociopathy. Seen up close, Shkreli does not become more likable, but more disturbing, because it becomes clear that he is willing to put on any facade necessary to get what he wants out of people. Ordinary, morally healthy human beings do not do this.

I am not simply exercising my imagination here. One of Shkreli’s ex-girlfriends has confirmed that he is a manipulative, psychologically abusive habitual liar with zero capacity for empathy. As she explained:

It soon became obvious that Martin was a pathological liar, would pretend to cheat on me and brag about it to raise his value in my eyes, so I’d always feel like I was hanging on by a thread, could be replaced, would vie for his approval and forgiveness.

Shkreli’s ex-girlfriend also displayed screenshots of conversations in which Shkreli offered to pay her ten thousand dollars for sex, a proposition that revolted her. Again, ordinary people do not do this.

His menacing behavior has been noted elsewhere: he has been accused of waging a harassment campaign against an ex-employee, writing in an email that “I hope to see you and your four children homeless and will do whatever I can to assure this.” The “Old World politeness” that so impressed the Vanity Fair correspondent appears to be hauled out for the benefit of journalists, only to vanish once they leave.

Both reporters know this, though. As Vanity Fair notes:

“Sociopath” is a not uncommon description of him. “Malicious” is the word another person uses… Shkreli says that the harsh words don’t bother him.

Note how the “sociopath” designation functions here: not as an enormous red flag that should make a reporter worry she or he is being manipulated, but as “harsh words” from a hostile public. Surely, though, if people tend to refer to someone this way, it should be seen as a warning rather than a badge of honor. Once again, ordinary, morally healthy people are rarely mistaken for malicious, destructive sociopaths.

Another writer, who went on a Tinder date with Shkreli and reported on it for the Washington Post, was also taken in by his disarming manner, even as he displayed exactly the same crass self-absorption we would expect:

He seemed the most genuine when he was acting like the guys I hung out with in high school (I dated the president of the chess club); that’s probably why I felt so comfortable on our date. We finished our food, and Martin flagged down the waitress and ordered the $120 tea. This was the most surprising and jarring moment of the night. I know he’s a multimillionaire, but I thought we were on the same page about this tea. He asked if I wanted a cup, and I couldn’t bring myself to say yes. When Martin finished his tea, I asked how he liked it. “I’m not really a big tea drinker,” he replied. What? I thought of all the good I could do with that money — donating it to charity, buying a new winter coat, buying myself 20 Venti iced soy vanilla chai lattes. He might as well have eaten a $100 bill in front of me.

Shkreli deliberately purchased the most expensive tea on the menu and drank it in front of this woman despite the fact that he doesn’t like tea. This is twisted behavior. Yet the Post writer remains sympathetic, concluding that Shkreli is “a lot more interesting and complex than I would have imagined.” Again, “complexity” here is used to refer to “that peculiar combination of charm and total lack of moral feeling that characterizes sociopathic individuals.” There’s no mystery as to what we’re seeing.

Another writer who interacted with Shkreli on Tinder also came out with warm feelings about him:

I do believe that Martin Shkreli believes he is doing good for the world, or else he wouldn’t have engaged with me. And even though Martin Shkreli is the current face of all that is wrong with capitalism, I do have sympathy for the guy. After all, even questionably sociopathic pharma bros deserve to get laid.

There are several problems here. First, it is peculiar to conclude that “because he engaged with me,” Martin Shkreli “believes he is doing good for the world.” What if, implausible as it may sound, Martin Shkreli simply cannot resist an opportunity to attempt to prove his intellectual superiority over others? We can apply a variation on Occam’s Razor here: why assume the more complicated explanation (hidden benevolent soulful core) when the more intuitive one will do (he’s an argumentative asshole)?

But even assuming Martin Shkreli does “believe he is doing good for the world,” what sort of defense is this? Hardly anyone believes their own actions to be evil, least of all evil people. To the contrary, everyone from the IRA to the Klan believes they are doing good for the world, that their worldview is the correct one. A person’s sincerity in no way excuses them; Donald Trump may sincerely believe that Muslims are a pox and Mexicans are rapists and that ejecting them all would be doing good for the world, but the honesty of his delusion doesn’t make it a shred more justifiable.

Second, what is this about sociopathic pharmaceutical executives deserving to get laid? Perhaps under a Bernie Sanders administration the right to coitus will at last be construed as a basic human social entitlement. But until such time, why on earth would we grant the idea that Martin Shkreli deserves so much as a sultry flutter of the eyelashes directed toward him, let alone that he should have the expectation of genuine human affection? If you’re unpleasant, people will not want to have sex with you. That should be the rule, lest unpleasant people begin to think unpleasantness pays unlimited carnal dividends. Referring to the importance of literary curiosity, John Waters once said that if you go home with someone, and they don’t have books in their house, “don’t fuck them.” A similar principle should apply here: if you go home with someone, and they turn out to make their living profiting from the desperation of sick people, perhaps reconsider rewarding them sexually for their crimes.

But the worst part of the Shkreli redemption-stories is that they give credence to Shkreli’s lies about his price gouging. Each allows Shkreli to pour out all manner of self-serving horse manure about how much he cares about AIDS patients, saying things like: “It’s our holy mission to make great drugs. And what we did with Daraprim is what it is. At the end of the day, the effort and the heart is in the right place.” He compares himself to Robin Hood, says he has “altruistic” motives and that nobody who needs the drugs will go without them.

Nothing he says can be trusted. He promised to lower the price of Daraprim in late September; now it’s February and the drug remains $750 a pill. He said insurance companies rather than patients would bear the cost; patients have been hit with co-pays up to $16,000. He insisted that the income from the price hike would be swiftly put back into new drug research; but in personal correspondence wrote that “almost all of it is profit.”

The facts on the ground suggest that real people are being hurt by Shkreli’s actions:

David Kimberlin had one month to get his hands on some Daraprim. His patient, a pregnant woman infected with toxoplasmosis, was due to give birth in September. But in August, the 52-year-old doctor, who works at the University of Alabama in Birmingham, learned of the drug’s price hike: a treatment that used to cost him $54 a month was now running at least $3,000. Babies born with toxoplasmosis need to be treated for about a year, with the total cost of treatment approaching $70,000 at the bare minimum. Fortunately, after a trip to the outpatient pharmacy, his pharmacist found a supply of the stuff already on the shelves—a break Kimberlin says saved the baby’s life.

During Shkreli’s Reddit “Ask Me Anything” session, a Daraprim user worried about how he would pay for the medication:

If they don’t follow through on their promises to provide it for free for patients like me for longer term, or if my insurance rejects the $27 per pill price, then I’ll be significantly affected. I am not a wealthy man by any stretch, and will struggle to afford the $27 price without finding a way to convince my boss to give me a raise or borrowing money for the next year. I don’t exactly have disposable income. I spend everything I make on my treatment.

Bear in mind, the commenter is worried about the $27-per-pill price that Skhreli promised. In actual fact, the medication remains at the astronomically higher rate of $750-per-pill. There’s no word on how this user has fared, but all of Shkreli’s showy professions of compassion are plainly fabricated. Again, not because of “complexity,” but because this is typical behavior for someone incapable of empathy and willing to tell whatever lies necessary to get what he wants, in this case favorable press coverage portraying him as thoughtful and many-sided.

But by far the most over-the-top defense of Shkreli came from the New Yorker’s Kelefa Sanneh. Sanneh made some of the usual points about the drug industry being the real culprit and so forth, but then got so wrapped up in Shkreli-love as to endorse Shkreli for the New Hampshire primary:

Last fall, Trump said that Shkreli “looks like a spoiled brat”; in fact, he is the son of a doorman, born to parents who emigrated from Albania. Look at him now! True, he has those indictments to worry about. But he is also a self-made celebrity, thanks to a business plan that makes it harder for us to ignore the incoherence and inefficiency of our medical industry. He rolls his eyes at members of Congress, he carries on thoughtful conversations with random Internet commenters, and, unlike most of our public figures, he may never learn the arts of pandering and grovelling. He is the American Dream, a rude reminder of the spirit that makes this country great, or at any rate exceptional. Shkreli for President! If voters in New Hampshire are truly intent on sending a message to the Washington establishment they claim to hate, they could—and probably will—do a lot worse.

This is plainly ludicrous. Holding everyone around you in disdain is not “never learning the art of pandering.” Trolling people on Reddit is not “having thoughtful conversations.” And Martin Shkreli only embodies the American Dream to the extent that the American Dream is to start with nothing and work your way up to becoming as much of an enormous rich asshole as possible. (Actually, come to think of it, this is not far from how the American Dream is usually portrayed.)

But one can understand the pressures that would lead a writer like Sanneh to publish something so stupid. In the world of online writing, spewing indefensible opinions is financially incentivized. In a #SlatePitch-driven media, writers are constantly competing to best each other for the most “counterintuitive” opinion. So we get a whole mess of articles like “The American Revolution Was Actually a Bad Thing.” Or, from Slate’s own Matthew Yglesias “Actually, Deadly Bangladeshi Factory Collapses May Be A Good Thing.” (Yglesias has now reached the logical endpoint of this reasoning, having suggested that the Nazis “may have had some good ideas.”)

These articles come about for obvious reasons; “It Is Bad When Factories Collapse and People Die” is not nearly as provocative as its converse. Fewer people would click on an article entitled “Wasn’t the American Revolution Nifty?” But here again, explanation is not justification. To take up immoral positions for the sake of Facebook shares is to dishonor the responsibilities that come with being a writer (or rather, being a person generally.)

The simple truth is that some positions should not be defended. The Nazis had no good ideas, factory collapses are tragic and must be stopped, and Martin Shkreli is neither interesting nor good, but a run-of-the-mill specimen of Wall Street vermin, albeit slightly more callous and two-faced than is standard even in America’s financial sector. The desire to find a novel journalistic angle should never outweigh one’s duty to acknowledge basic facts of the universe. Some things are simply true, with no contrarian angle to be taken, and that’s perfectly alright.

It therefore remains worthwhile to hate Martin Shkreli, and to hate him intensely. Forget the questions over drug pricing; what we have serendipitously found in Shkreli is a convenient public example of everything a human being should strive not to be. Shkreli may have ignited a debate about access to medication, but his real social function is even greater: he displays all of the traits that our species must exorcise if we are to build a just and decent world. He is greedy, smug, and vulgar. He is a liar and a braggart. He treats women abominably. He is contemptuous of those he considers his lessers. His literary curiosity stops at Ayn Rand. (Actually, the Cliff’s Notes to Ayn Rand, according to the reporter who looked at his bookshelf.) He doesn’t just wish to amass pleasures for himself, but to deny them to others (witness his purchasing the sole copy of a $2 million Wu Tang Clan album and threatening to destroy it.) He toys with people for his own amusement. He can be charitable, but only when it pleases him, for what motivates him is not the desire to maximize human good but to maximize his own power over others.

In short, even the people who have most loudly denounced Martin Shkreli have insufficiently appreciated just what a blight he is. Never mind “Shkreli is not the real problem.” Shkreli is, in fact, the only problem, for once we can eliminate every little bit of Shkreli from ourselves, human beings will have reached perfection. We should teach about him in schools, cautionary sermons should be preached against him. Mamas, don’t let your babies grow up to be Shkrelis.

All of these attempts to redeem Martin Shkreli must fail, then, so long as there is a glimmer of mercy and decency in the world. Of the many problems with the drug industry, Martin Shkreli may only represent only one of them. But of the many problems with humanity as a whole, Martin Shkreli represents essentially all of them.