How Corbyn Was Thwarted and How to Rebuild the British Left

Labour activist and author James Schneider explains what went wrong and how a left movement can succeed in the UK.

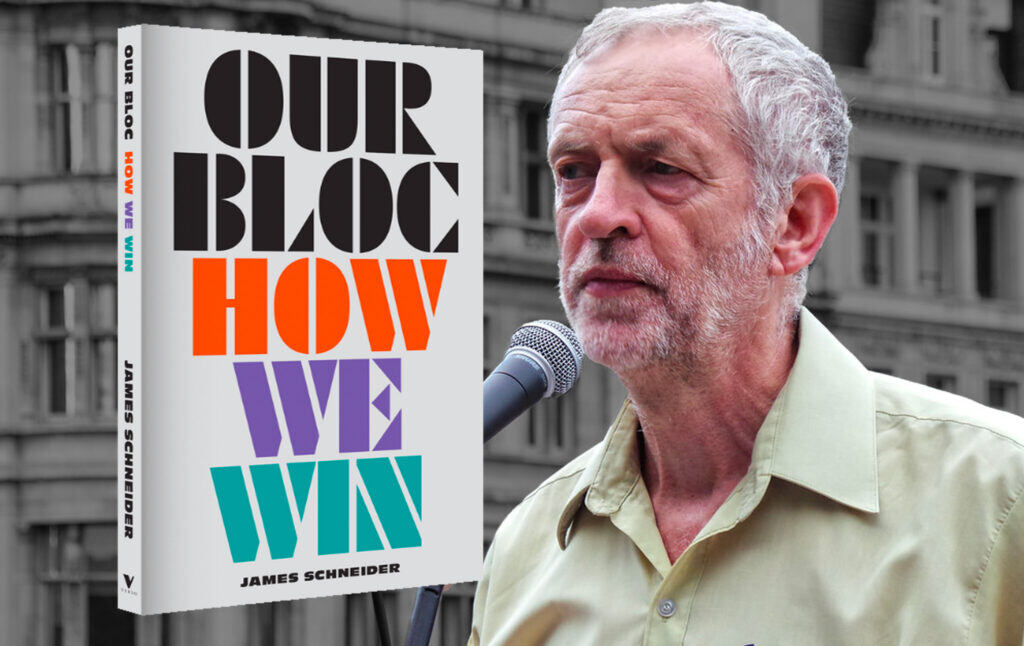

James Schneider is a co-founder of the British leftist organization Momentum, and served as strategic communications director for the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn. Schneider is the author of the new book Our Bloc: How We Win, which lays out a clear plan of action for rebuilding the British left. Even though the book focuses on Britain, there are a lot of important parallels and lessons for the U.S.

For those who don’t know the background, socialist Jeremy Corbyn was elected leader of the Labour Party in 2015, and led the party to an incredibly impressive election showing in 2017. But then things fell apart, and in the 2019 election Labour faired far worse, forcing Corbyn from the leadership (see CA pieces here and here). The party is now run by a centrist who despises the Corbyn movement, and who went so far as to kick Corbyn out of the party itself.

James, who saw the whole thing unfold from the inside, joins us today to explain what happened and why, and to lay out the prospects for revitalizing the British left after its depressing recent defeat. The conversation originally aired on the Current Affairs podcast and has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

I am hoping you can describe the present state of UK politics to our mostly American audience. I wrote back in 2017 about the ascendance of Jeremy Corbyn to the leadership of the Labour Party, which was immensely exciting, coinciding as it did with the Bernie Sanders campaign here in the US. There was this wonderful moment where it felt like anything was possible, and that the major parties in both the UK and the US were going to fall to the socialist left.

It did not happen, and everything somewhat unraveled for the left in the UK after that high point in 2017.

My first question is: What the hell happened?

Schneider

In one word, Brexit. In the UK, that was the biggest factor that undermined the Corbyn project—their biggest contingent factor. There are other structural factors we can come to, but the biggest contingent was Brexit. We fought two general elections with Jeremy Corbyn as leader in 2017 and did very well. We got nearly 13 million votes, over 40% of the vote—2% behind the Tories who took away the governing majority—and rose by 25 points in the polls. At the beginning of the election, we started at 24% or 23%, so it rose by nearly 20 points in the polls. In that election, we were able to turn it away from being a lecture about Brexit and the way in which Britain would leave the EU, towards being a divide between the many and the few—a basic and broad class antagonism. It was very effective, with the kinds of social democratic policies which everyone loves, and always has loved. Actually, if you look at the polling, people really have always liked, and now especially like, things like public ownership of utilities, proper and universal funding of public services, taxing the rich and big business, and so on.

Robinson

Yes. To dwell on this for a moment, the media consensus about Corbyn when he came in was, “This guy is fringe”; “Labour is going too far to the left”; “You would alienate the public.” Many articles were saying this was going to be the end of the Labour Party. And as you say, you put forward this agenda, and what actually happened is it was a test of the popularity of left policies and saw that it actually helped rebuild support for the Labour Party that had been flagged.

Schneider

Absolutely. And actually, the manifesto—the set of policies in the election campaign—were leaked, maliciously, before they were published. They turned out to be an enormous boon for us because the fact that they were leaked was exciting. It made it a spicy news story: “Who did it?” and “Why?” and so on. But it also meant the media thought the policies were crazy: “My goodness, Labour are going to tax the rich and nationalize energy, water, and trains!” And most people instead thought, “It means our trains won’t be run by private companies paying billions to shareholders and pumping sewage into the sea and our rivers. Well, that sounds quite good, actually!”

And that was basically the best coverage we could get. Then by the time we get to 2019 to talk about what went wrong, that election was entirely about Brexit. So, the main divide was a terrible one for Labour because it cuts right through the electoral constituency that you’re trying to build. The vote to leave the EU was 52-48, but if you map it onto parliamentary constituencies, it was 420 to “leave”, and 234 to “remain.” In a parliamentary system, being on the “leave” side of that was going to help, and the Tories had a strong and clear message on Brexit. Instead, we had a confused message on Brexit.

Robinson

As you say, it’s almost impossible for the Labour Party to come up with a good message on Brexit because you have so many people who are staunchly pro-remain. I think it’s clear at this point that Brexit was a disaster or a mess. But you have a huge push for trying to win back the working class who voted for Brexit as this anti-establishment thing. What can you do?

Schneider

With the benefit of hindsight, there are some things that we could have done. If we had built a bigger story about democracy, and said that this vote is the beginning of democratizing British politics, society, and the economy, and took the potentially left populist elements of Brexit (of course, there are many other elements of Brexit which are not left) and many other things that we wanted to do—like big thoroughgoing reform of the state, democratizing the economy, and so on—and then turned that into a narrative that people who voted “leave” and “remain” would both like.

But, there was a real problem when the balance of forces in the Labour Party—in terms of its membership, MPs, and constituents—being extremely on the “remain” side. For many of the MPs, Brexit was part of the same phenomenon as Jeremy Corbyn becoming leader. It’s their whole way of understanding the world, which is basically they, the clever people with their friends in think tanks and corporate lobbying, can come up with clever tricks to make things slightly better or less bad, and that’s really what grow-up politics is all about. And then suddenly, you get these two big intrusions into it which say, “No, you lot are terrible, the country is getting much worse, and your style of politics has helped do it,” one being the vote to leave, and the other being Jeremy Corbyn, and so they reacted quite viscerally against it.

Robinson

That helps to explain why the 2019 election result went as it did, but it’s also the case that Jeremy Corbyn subsequently lost control of the Labour Party. I don’t even know if he is still technically a member of the Labour Party or not.

Schneider

He’s like the opposite of Bernie Sanders. If Bernie Sanders is not a member of the Democrats, but caucuses with the Democrats in Congress, Jeremy is the opposite: He is a member of the Labour Party, but he is not allowed to caucus with the Labour MPs, in part.

Robinson

How did that happen? How does he go from the leadership to exile?

Schneider

Defeat was highly disorientating, and part of that defeat was about the right block hearing the Tories did extremely well and got 45% of the vote, and were able to mobilize people who had voted to leave in 2016 and hadn’t voted in 2017, with nearly two million people in that category they got out to vote in 2019. By way of comparison, David Cameron, when he won the majority in 2015, got something like 36% of the vote. So, the Tories did put on a lot.

We got, in terms of votes, bang slap in the middle of what is ordinary for the Labour Party to get. In the last 10 general elections, 2019 is the fifth highest of the Labour votes, but the Tory vote was so much higher, which means that we lost loads of seats and ended up with only a little over 200 seats in a 650 seat Parliament.

And then there was a leadership election, and from the left there had been good succession planning or anything like that. The leadership campaign had a left candidate, Rebecca Long-Bailey, who wasn’t particularly forceful and not very able to draw dividing lines with the other main candidate, Keir Starmer, who eventually won. Keir Starmer had, in terms of winning in the Labour Party, an excellent approach because he said, “I’ll do 80% of Corbynism, but I’ll win. I was in Jeremy’s team, and I’m not going against what he went for. What has happened in the party is excellent, but the only thing that isn’t is we didn’t win. I’m going to shave off some of the edges. I wear a suit, I’ve been knighted by the Queen, and I will do the radicalism. Don’t you worry about it at all.”

Robinson

So, he lied. The strategy was “lying.”

Schneider

It’s unbelievable. He has ten pledges that he stood on, which even at the time we were saying, “Look at what’s missing.” On first sight, they look like a basic statement of the 2017 manifesto, but each one he massively backtracked on. Yes, the guy straight up lied. I know Keir Starmer and got to work with him very closely in my job. I was basically Jeremy Corbyn’s or the Labour Party’s press secretary, and didn’t trust him. I thought he wasn’t a leftist, and this isn’t what it’s going to be. But then the turn to reaction has been so fast and hard. Basically, a reversion to high Blairism.

So, with Tony Blair in the New Labour government in the first term, there was some carryover of basic Labourist tropes, at least, and some of that in the policies. But by the end of Blairism, it’s all about the War on Terror, attacks on civil liberties, and marketization of public services—that’s the mania that they got into. And it’s gone back there, pretty much. To cut a long story short, Keir Starmer seized an opportunity to, firstly, kick Rebecca Long-Bailey—his rival for the leadership who he had in his top team in the Shadow Cabinet—out after two or three months. And then two or three months later after that, he saw an opportunity to remove Corbyn. First, he stripped him of the membership, then that went through the party system and was reinstated. And then he said Corbyn can’t caucus with MPs.

Robinson

And just to be clear, this was on what grounds?

Schneider

This was that Starmer didn’t like Corbyn’s response to the Equality and Human Rights Commission’s report into antisemitism in Labour. Corbyn’s response to it said that mistakes are made and so on. “One anti-Semite is one anti-Semite too many, there were failures made, and also, those failures were overstated for political purposes in the media and political opponents, and that combination hurt Jewish people,” which is a statement of fact.

Robinson

I do think it’s important to clarify this for people who are not familiar with the background here. You have mentioned here one major reason why the Labour Party under Corbyn lost the 2019 election, and also mentioned the strategy Keir Starmer used to successfully seize control of the party. In the background, there was this giant campaign to discredit and undermine Corbyn, often from within the Labour Party, and about how Corbyn was fostering an antisemitic Labour Party and tolerating antisemitism. I call it a fake scandal. I think the people pushing these antisemitism charges mostly did not care very much about antisemitism. Anytime that he or those allied with him, as I understand it, responded by trying to say this scandal is a little disingenuous, considering that he has a record of strongly opposing antisemitism, this was used as evidence that he didn’t take antisemitism seriously.

Schneider

Yes, that’s mostly the case. There are three elements to the Labour antisemitism thing, and they interlock, and we didn’t deal with each of the three things particularly well. I’ll give a small anatomy of it. The first part is there is a small but nevertheless notable number of antisemites on the left. There are antisemites throughout society, and they are also on the left–that’s the case. Also, many people don’t know very much about antisemitism. Fine, that’s one thing. So, there are little things that can be picked up on because there is a real issue there, it’s just there’s a question of scale. Then there’s the second thing, which is everything is absolutely seized on, sensationalized, or taken out of proportion for political purposes in the media and through political opponents inside and outside the Labour Party. The third element is over the definition of antisemitism, and the attempt by the Israeli state and other allied groups to render anti-Zionism by definition antisemitism. These three things all collide and gave a constant feed of stories which they kept on going with because then anyone’s outrage about something can set up a whole new cycle of stories. So, it kept on running and running. I don’t think the actual issue itself was moving very many votes.

Robinson

I wanted to ask you that: How much did it actually matter?

Schneider

I think it mattered a lot indirectly, but not very much directly. I don’t think very many people in Britain move their vote directly about it. But firstly, if you zoom out, most people don’t follow politics day to day very sensibly, and watch it in a zoomed out way with the volume turned down, if not turned off. And if all you’re seeing for a few years is “Labour antisemitism” in the headlines all the time, what you’re really seeing is “Labour problem” and they can’t fix it. So, it speaks to your competence. It’s not really the issue of antisemitism. That’s one thing. And then the second thing is, Jeremy finds it very difficult and painful to talk about. In interviews in 2019, 50% of the airtime is taken up with Brexit and antisemitism, subjects where we aren’t strong, versus the rest of the time when we can talk about, “Why not have a higher minimum wage, close some tax loopholes, have public ownership of rail, and free college education?” It has that indirect effect.

Robinson

Yes, it just gets in the way. It’s a big block between you and your ability to reach people on the issues. That third thing that you mentioned I’m well familiar with personally because I was a Guardian political columnist until I was fired for “antisemitism” for criticizing US military aid to Israel. I have some background with that myself.

You might want to say “no comment” on this: I always felt Jeremy Corbyn is too nice of a guy for politics, as someone who doesn’t want to go too much on the attack at a time when I feel like you should go for the jugular.

Schneider

He’s a very nice guy. He likes to stick to the issues. But to be honest, often those are the times that I thought he was his most powerful. For example, one year into his leadership, in 2016, most of his MPs launched a coup, and tried to get rid of him as leader. He was under lots of political pressure. And he was giving a speech, saying, “Some people say to me, I’m under pressure. I’m not under any pressure at all. Real pressure is not knowing how you’re going to pay the bills at the end of the day and feed your children, or you’re going through a mental health crisis and you can’t get support. That’s real pressure.” That’s so much better than turning around and saying, “The other lot are a bunch of wankers.”

Often, people’s strengths and weaknesses can be the same thing. His ability to not get too caught up in the day to day of politics and the nonsense is seen as being naive. And in some cases, that can be a bit naive, but also in many other cases, it just means you’re focused on real things you care about rather than whatever the latest media babble outrage of the day is.

Robinson

He sticks to the policies and to the things that matter, which I like. Why is it, though, that Keir Starmer has successfully defrauded the Labour Party into putting him in the leadership by promising essentially social democracy and then delivering pure neoliberalism? It’s to the point where I think he does not even see it as a Labour Party. When the rail strike started happening, he started to say, “It’s not the position of the Labour Party to take a side in an industrial dispute,” i.e., a labor dispute.

Schneider

There are a lot of these very funny clips of him on picket lines, saying, “It’s crucial that politicians are here with you, showing that they support and are with you in struggle.” But his line is, “Because we want to be a party of government, we can’t take a side. But strikes aren’t going to happen under Labour because “growth”, and we’ll responsibly get around the table.” And then the interviewer says, “So would you give the nurses, not a pay rise, but not a pay cut?” He responds, “It would be irresponsible to throw numbers around. These are independent negotiations.” Yes, but you want to be one side of the negotiation.

Robinson

You’re the Labour Party! That’s your side! You’re on the side of working people, supposedly. He gets into power, and you’ve got the leadership of the party, but surely if the party membership had elected Corbyn before, and because it took that kind of fraud for Starmer to succeed, we would assume that the party base is still pretty social democratic. Is it the case that he has full, consolidated power over the party, or is it this guy is going to become really unpopular pretty fast? Why can’t the left get the leadership of the party back? Assume I don’t know how British politics works, and I need this explained to me.

Schneider

I’ll start with the membership because that’s where you started your question. Starmer won quite convincingly, and at the time, the membership was about 600,000. Now it’s under 400,000. They don’t publish the figures, but it’s somewhere between 350,000 and 400,000. Over 200,000 people have voted with their feet, and many of those will be overwhelmingly on the left. But if you look at polling of Labour Party members and the latter internal party elections, the left and the right are basically in even balance, even though we are three years down the line from when all this stuff has happened. On policies, the membership is obviously still very much on the left, except for the machinery of the party, which is what the right-wingers have spent the whole time doing. When they lost the party because Jeremy won the leadership, they could have spent five years thinking about what a program for government would be—what are the policies to deal with, issues of the day, etc.—but then come up with a single policy, they just keep on going back to that late Blair government thing.

Robinson

Coming up with policies would be taking sides. We’re the government, and that doesn’t take sides.

Schneider

They spent a lot of time thinking extremely effectively about how to make sure Jeremy Corbyn never happens again. They’ve made a whole series of changes to the internal structure of the party, which is really how power works. For example, you needed 20 MPs to get on the ballot to run for leader. That’s now gone up to 40—there aren’t 40 left MPs. So, there you go, there’s not going to be a properly left person on the ballot for the next lead. That’s one thing. The National Executive Committee—this is going to sound very technical—is a committee of 44 or 45 people, and only nine of them are elected from the membership, and they change the electoral system to a single transferable vote. So beforehand, the left would get all nine, and then they changed the voting system. At first, the left got five, and then four, as in it is basically balanced between the left and right—a lot of the other positions will be on the right automatically because their appointees are from the parliamentary party, the Shadow Cabinet, and from the leader. In terms of control of the party, they’ve taken very firm control, but they haven’t won the hearts of the grassroots, anyway,

Robinson

So, the Party’s internal procedures have now been modified and rigged to minimize the chance that the left can succeed in the party. And as you say, the membership, hundreds of thousands of people who might have joined because they’re inspired by Jeremy Corbyn have said, essentially, “Well, fuck this,” and left, so you have a less powerful left within the party.

But I believe in the book, you argue that it would be a mistake for the left to shun the Labour Party, that there is no route to building an independent left party in Britain, and that you have to, and can, re-seize control of Labour. If not, please correct me.

Schneider

That’s not quite what I’m saying. Because of the misery of our defeat, people have basically said we should do one of three things, and they’re all the defeated strategies that we pursued before Corbyn. One is set up new, small left parties without substantial social movement or trade unions or anything else, which in our electoral system is goes nowhere.

And I argue if we were to do that, the same thing would happen. In fact, there have been three or more new parties set up, and there will be more that will set up this year, I’m certain. You won’t hear their names and nothing will happen with them, in part because you need to have a social weight with trade unions, activists, and social movements.

The second one is a kind of Labour left quietism: “We’ll just wait and hope, and then maybe we’ll get another shot at it again,” but where you’re basically bleeding out because people are leaving all the time and quiting. And then the third one is to say electoral politics is painful and rubbish: “Let’s not do it, we just need to have these spontaneous or semi-spontaneous resistances that spring up from time to time now.”

I think none of these are sufficient for the scale of the issues that we’re facing in the world, as in with climate breakdown, global debt crisis, with the cost of living scandal, and so on. And we can’t abandon the state; we don’t have the luxury of changing the world without taking power. And most of the base asks: Labour Party—yes or no?

Again, I think that’s putting the cart before the horse because we tested the theory about the Labour Party with Jeremy as leader. The reason why we lost was not because the party was irrevocably right-wing and has done the things that it’s now done. It wasn’t doing those things once we took enough control. Of course, there was civil war and fighting against us. But the thing that we didn’t have was sufficiently developed progressive social forces in society that could all mobilize together.

So, my argument is that we need to knit together as much of the left progressive and small “l” labor forces that we can, including the left MPs in the Labour Party, with the environmental movement, left trade unions, with Black Lives Matter, and so on, into a bloc, which will bringing them together, strengthen each of their individual campaigns, and help us project left ideas into society because we’ve basically been chased out of the public domain since losing in 2019.

And I think it makes us to be in the strongest position to take advantage of whatever political situation comes up. As I argue, that could potentially be taking back control of the Labour Party, or causing a real split with it. Starmer’s people could decide, “No, hell with the trade unions,” and then get a new party, but one that has a social weight with hundreds of thousands of members, activists, and organization, and has a reason for forming that people in the public might have heard about because it comes about from out of the party.

Or there are other things—I sketch out different sorts of plausible scenarios. At the end of the book there are four of them, and in some of them the Labour Party is significant, and in others it’s somewhat irrelevant. I think that we should be a bit humble about knowing the future. Without these events, Jeremy Corbyn would not have become Labour leader. In 2013, a man called Eric Joyce, who was a Labour MP, punched a Tory MP in a pub in Parliament. If that punch had not taken place, Jeremy Corbyn would not have been Labour leader, and we would not be talking now.

Robinson

You’re going to have to explain this butterfly effect here.

Schneider

So, this guy, Eric Joyce, punched a Tory MP and had to resign from Parliament, and there was a by-election for his seat in Falkirk, Scotland. In the constituency is a big petrochemicals plant where Unite, the trade union, is strong, and were putting forward their candidate, Karie Murphy, who at the time was Tom Watson’s office manager. Tom Watson was Jeremy Corbyn’s Deputy, the leader of the right in the Labour Party, and later became his Chief of Staff.

And the Labour right really didn’t like this idea at all. They threw around all sorts of accusations that there was vote buying going on and that Unite was buying this parliamentary seat by buying memberships for Murphy. It caused such a stink, with the press saying this shows “evil union barons corrupting politics” and all these familiar tropes, and putting pressure on the then leader Ed Miliband, so much so that he called the police on Karie Murphy and on Unite, the biggest trade union in Britain and the biggest donor to the Labour Party. But the police investigated, and nothing happened. But in this political scandal, the idea came up that Ed Miliband had won and beat his brother in the 2010 leadership election through the votes of trade unions.

So, his idea was, let’s reform it so that trade unions get less of a say in the leadership election. The Blairites had always wanted to take power away from party members; they think party members are weird people who like politics too much. They wanted to give votes to normal people because normal people won’t be left-wing—that’s their thinking. So, they opened up the system to just one member/one vote. If you’re a trade unionist, you can sign up and get a vote, or if you’re a registered supporter, you can pay three pounds and vote, turning the Labour leadership more into something like a primary in the US rather than a vote among its constituent parts. And this is what the right-wing wanted—this was their thing. That system allowed Corbyn to win.

Robinson

So, it all began with a punch.

Schneider

We should have some humility. I don’t know who is going to punch who in what pub and what effect that’s going to have. It’s a strategic point of view: we’re better off assessing where our resources are, and how we can make those stronger so that we have the capacity to take advantage of contingent openings.

Robinson

When I characterized you, you were disputing the people who say we should take one of the three paths that you laid out— that we should all leave the Labour Party and form an independent party. But you are not laying out some very specific blueprint for taking power within the party—you’re saying that’s the second phase. The first phase is to ask: How do we build a broad based independent movement that can then strategize about how to get back into power?

Schneider

Yes. Let’s look at practically where things are in Britain now. You were saying things look pretty bleak in Britain, and you’re not wrong. It’s going to be the biggest fall in living standards ever, and that comes on the back of 12 years of falling living standards. Median pay in Britain now is lower than it was in 2005. Public services have been cut, the NHS is in crisis, etc. We have inflation and the climate crisis, which people are much more aware of because it got to over 100 Fahrenheit all over England in the summer, which is unheard of. And for energy bills, the new cap is over 4000 pounds a year that they’ve just bought in.

So, there is a whole load of resistance that’s taking place. There is a strike wave of ambulance workers, nurses, train drivers—all sorts of people are on strike. There are well over a million people who can’t pay their energy bills and many people on strike refusing to pay them, rents for housing have gone up and tenants are organizing, and we’re having the biggest wave of climate direct action that we’ve had, and the state is cracking down hard on that. It seems to me that as much as these traditional types of resistance can be brought together and can strengthen one another and shake the ground that politics sits on. It will shake the ground within Labour, between Labour and the Tories, and elsewhere, and could provide some organizational structure that we’ll be able to take advantage of, whatever the next opening is.

Robinson

I don’t want to put words in your mouth here, but it seems the implication of what you’ve been saying is that one problem facing Corbyn in 2017 was that he found himself unexpectedly in a high position of power, but did not have the backing of a giant and popular movement of the kind that is needed. I think the same thing happened with Bernie Sanders where he more or less stumbled into success all of a sudden and took him completely by surprise. He thought he was going to be a fringe candidate and didn’t have a popular organization behind him, and had to cobble together a movement on the fly to deal with the fact that left policies were really appealing to the population.

Schneider

Yes, it is very similar in that way—it was a sort of shortcut. And again, after we lost, one of the things that became trendy to say is we shouldn’t be looking for shortcuts and leaps forward. I think this is wrong, history does move in surges. If you look at trade union membership drives, what does the membership of trade unions got? It’s in dispute. It’s in the surges, and that doesn’t mean that in the times in between you don’t need to have the careful quiet organizing, but things do throw you forward, and you need to then institutionalized them and build power around them. What I’m trying to do in this book is turn around some of our collective loss of self-confidence that we experienced.

The defeat in 2019 was a big pain. There are many things that have grown up in the last few years that we’ve all worked for and built that could dissipate and be scattered to the four winds, or could come together in a new formation. It’s not going to be the formation that we had, where everything cohered under one strategic horizon, which is Jeremy Corbyn. There’ll be a different formation, but we can bring those together, and that’s going to be our best way of challenging power because it mobilizes as much popular power as we can muster.

Robinson

One thing you say in the book that I’d like to hear you say more about because it went against my own biases and preconceptions, was that you say we should actually pay attention to how much of a success the British Conservative Party has had. My simplistic outsider’s perspective would be that Conservative success is because of Labour failure. If you didn’t support the Iraq invasion and put a bunch of uninspiring neoliberals in charge of the left party, you’d probably do a lot better. But you say that we should actually pay attention to the fact that the British Conservative Party has been pretty adaptable and flexible in its ideology. It’s a formidable party in certain ways.

Schneider

Yes. Depending on how wide you cast the net, you could say it’s the second most successful electoral party, after Japan’s Liberal Democrat Party. I’ve got a figure in the book, 68 of the last 100 years they’ve been in government—something like that. I do think it’s worth paying attention to your opponents. That all said, when I was writing the book and the analysis of the conservatives, Boris Johnson was not only Prime Minister, but he was riding high.

Robinson

This is before the Liz Truss era of British Conservatism.

Schneider

And you don’t get any credit for writing something that then came true in a draft that wasn’t published because books work on a slow timescale. But when Johnson was riding high, I was saying he has a potentially hegemonic strategy which could be short to medium term successful, but many of the Tories don’t like it at all. Their internal tendencies could easily come back to the fore, which will likely be headed by Truss and Rishi Sunak, which we’ve had both of them as Prime Minister this year and last year.

Robinson

To conclude here, can you tell us a little bit about Momentum and what it does for the work that you do, and how you see it fitting into the strategy that you lay out here?

Schneider

We founded Momentum on the back of Corbyn’s first leadership campaign in 2015. It was founded to not demobilize. We had a huge leadership campaign—unheard of by British political standards—with 17,000 volunteers around the country. We didn’t want to demobilize this, so we set up Momentum to support Corbyn, and it ended up innovating all sorts of things in campaigns, digital, video, and member mobilization, and did plenty of good things.

To be clear, I’m still a member of Momentum, but left in 2016 to work for Corbyn directly. So, I’m not speaking on its behalf. Momentum has had two turns since Jeremy lost leadership, and I think they had them slightly in the wrong order. Firstly, they wanted to democratize Momentum and turn more outwards to social, environmental, and small “l” labor struggles. And now they’ve had another set of elections, and turning to focusing more tightly on organizing and the Labour Party.

I think they probably should have done it the other way around, to hold the position as much as possible, and then if you want to hold a position in the Labour Party—which would be a good thing—you’ve got to use the energy, which is not coming internally from the struggle within the Labour Party, but instead coming from the struggle in society. There was a reason why the struggle in the Labour Party had so much energy during the Corbyn period: it was the front line of the political struggle for people to get the things that they want–the policies and improvements in people’s living standards and services that people deserve.

Holding on to the Labour Party for Corbyn and getting more left people elected was the serious frontline of the struggle, and that’s not the case now. The energy is coming from the campaign to not pay energy bills, the striking workers and climate direct action, and plenty of other things as well—that’s really where the energy is. That’s what Momentum particularly has to be porous to, to be successful.

CORRECTION: The by-election held in Falkirk was originally written to have been in Sterling. The text has been updated.

Hear this conversation on the Current Affairs podcast. Edited by Patrick Farnsworth.