Seeing Martin Luther King As A Human Being

King should be appreciated in his full complexity.

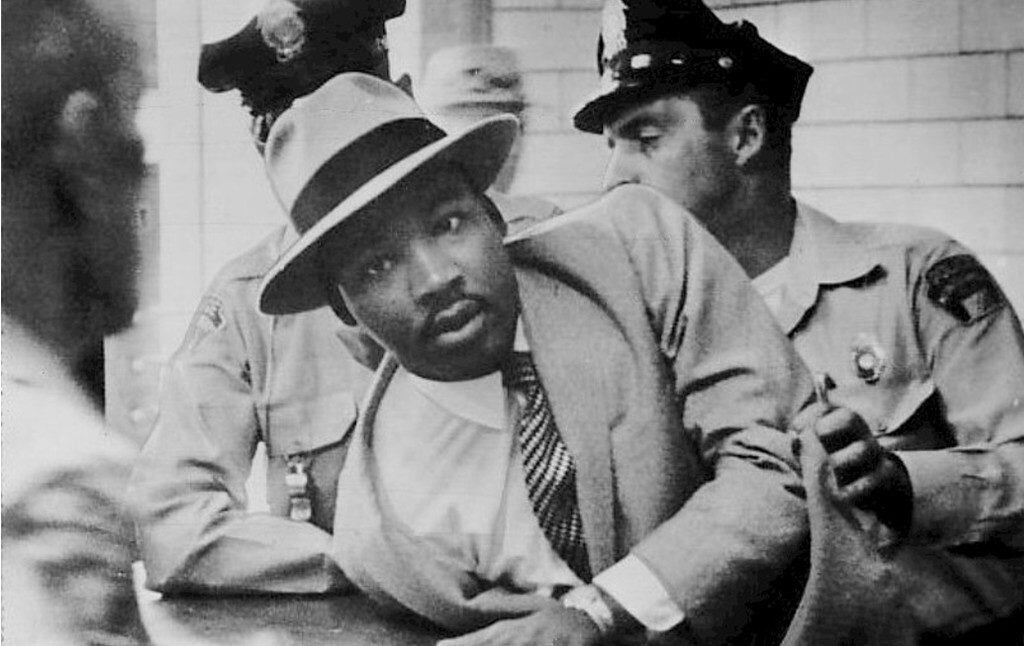

Every Martin Luther King Day is the same: first, we get the incredibly vapid and insulting celebrations of MLK the harmless saint, like Fox News chastising people for “politicizing” King (even though King spent his entire adult life as a political activist) or former FBI director James Comey speaking fondly about “Letter From Birmingham Jail” (without mentioning the FBI’s own letter to King encouraging him to kill himself, or the fact that the Birmingham letter is a scathing indictment of white moderates). But MLK day also comes with its obligatory exasperated leftist responses, as historians and activists try yet again to successfully remind the public that King was not, actually, a dealer in empty slogans about “unity” and “togetherness.” He was a radical leftist who despised the Vietnam War and believed in the large-scale redistribution of wealth:

“The country needs a radical redistribution of wealth.” — Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“God didn’t call America to engage in a senseless, unjust war as the war in Vietnam. And we are criminals in that war. We’ve committed more war crimes almost than any nation in the world.” — Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The good news is that, because socialism is winning the battle of ideas these days, even CNN and Teen Vogue are doing the “Actually, Martin Luther King would not have liked John Roberts” take. The King that people learn about in school is still the King of “I Have A Dream” rather than the Poor People’s Campaign and the Riverside Church speech. But thanks to writers and scholars like Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor and Tommie Shelby, there is an increasing appreciation for King’s actual thoughts and writings, as opposed to the “neutered,” unthreatening, ideologically nondescript King of postage stamps and children’s books.

Since I am a leftist, my first urge on Martin Luther King day is to join the pleas to understand the real King, the radical who read Marx and thought the U.S. was an imperialist country, who questioned capitalism and believed that economic injustice and racial injustice could not be separated. But I also know that this, too, risks “flattening” King into a set of notions rather than a person. They do happen to be the notions he actually held, which makes claiming King for the radicals far better than, say, writing a book called Kingonomics: Twelve Innovative Currencies for Transforming Your Business and Life Inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. But I still want to be careful not to use King as a symbol and to try to understand him as a flesh-and-blood human being.

King also poses his own set of challenges to leftists. He was, of course, uncompromisingly opposed to war, racial injustice, and economic exploitation. But the absoluteness of his commitment to nonviolence still poses many discomforting questions for activists. In his time, King was seen as a moderate and a compromiser by leaders like Malcolm X, who thought King was encouraging black people to “be defenseless in the face of one of the most cruel beasts that has ever taken a people into captivity.” Many black radicals broke from King, seeing his nonviolence as a failed and suicidal approach to achieving liberation. “Black power” originator Kwame Ture (born Stokely Carmichael), for instance, had been close to King but gradually came to feel as if his methods were based on a rosy and naive view of race relations:

Dr. King’s policy was that nonviolence would achieve the gains for black people in the United States. His major assumption was that if you are nonviolent, if you suffer, your opponent will see your suffering and will be moved to change his heart. That’s very good. He only made one fallacious assumption: In order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none.

Strategic and moral questions about violence are still relevant today, and still bitterly contested. King’s uncompromising position can be difficult to accept, because it seems to suggest that someone who is being attacked should not defend themselves, or even had no right to. Nonviolence, if taken to its extremes, can lead one to adopt Gandhi’s radical position that the Jews in Nazi Germany should simply have made a moral statement by offering themselves up willingly to be slaughtered.

King’s position was not Gandhi’s; he insisted that he was not a pacifist, and he emphasized strongly that when he talked about “nonviolent resistance,” the “resistance” was just as important as the “nonviolence.” He resented attempts to conflate “nonviolence” with inaction or passivity, and usually spoke of it in strategic rather than purely moral terms, arguing that violence was not just wrong but futile:

The ultimate weakness of violence is that it is a descending spiral; begetting the very thing it seeks to destroy. Instead of diminishing evil, it multiplies it. Through violence you may murder the liar, but you cannot murder the lie, nor establish the truth. Through violence you may murder the hater, but you do not murder hate. In fact, violence merely increases hate. So it goes. Returning violence for violence multiplies violence, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that.

There are still criticisms to be made of this; violence has stopped violence before, and the “descending spiral” is not an inevitability but a tendency, one that can be mitigated with an understanding of the uses and limitations of particular kinds of violent methods. We can understand why many of King’s contemporaries in the mid-’60s, seeing the slow progress of desegregation, the acceleration of white flight, police violence, poverty, and the disproportionate drafting of black men to fight and die in Vietnam, thought of King as, well, a dreamer. King’s belief in the radical power of love stemmed in large part from the intensity of his religious faith, and to anyone who didn’t share that faith, it may well have seemed baseless, irrational, and foolish. For critics, nothing better proved the point than King’s own assassination in April 1968: there, that’s what love gets you.

Yet regardless of where we come down on the Martin/Malcolm debate over violence, King’s willingness to stick by his principled nonviolence, even as the world erupted in flames around him, should impress us as an act of courage. The hagiographies of King often neglect his inner struggles, and the extraordinary effort it took for him to maintain his resolve. He was not superhuman, but a person who suffered from doubts, temptation, and fear, even anxiety. King’s decision to oppose the Vietnam War, for example, was not an easy one. He had been told that it would destroy his political capital with Lyndon Johnson. He had been warned that he would be seen as anti-American, and that public sympathy for civil rights goals could be irreparably damaged. Yet as King sat in a restaurant, flicking through an article in Ramparts magazine about the civilian toll of the Vietnam War, he came to the painful conclusion that there was no moral way to stay silent, even if taking a public stance would lose him friends and political influence. King looked through photos of burned Vietnamese children in hospitals, read accounts of the destruction of villages and the napalm bombing of civilians, and wrestled with an impossible question of conscience: How can I confine my cause to the advancement of my own people? Isn’t injustice anywhere a threat to justice everywhere? I think it’s important to appreciate why this was not easy: the antiwar movement in the United States was widely loathed. We think of ’60s protesters as defining the era. In fact, they were always in the minority, and even in 1967 most people supported escalating bombing in Vietnam. King really did face the serious possibility that he could harm the interests of Black Americans by speaking out for the Vietnamese.

Some of King’s gravest moments of self-doubt came in 1955, at the beginning of his activism in Montgomery. He was newly married, and the floods of death threats and obscene phone calls that he had begun to receive made him wonder if he could stand to press forward with civil rights work. The following excerpt from David Garrow’s Bearing the Cross describes the inner turmoil King faced:

“I felt myself faltering and growing in fear,” King recalled later. Finally, on Friday night, January 27, the evening after his brief sojourn at the Montgomery jail, King’s crisis of confidence peaked. He returned home late after an MIA meeting. Coretta was asleep, and he was about to retire when the phone rang and yet another caller warned him that if he was going to leave Montgomery alive, he had better do so soon. King hung up and went to bed, but found himself unable to sleep. Restless and fearful, he went to the kitchen, made some coffee, and sat down at the table. “I started thinking about many things,” he recalled eleven years later. He thought about the difficulties the MIA was facing, and the many threats he was receiving. “I was ready to give up,” he said later. “With my cup of coffee sitting untouched before me I tried to think of a way to move out of the picture without appearing a coward,” to surrender the leadership to someone else… “I sat there and thought about a beautiful little daughter who had just been born …. She was the darling of my life. I’d come in night after night and see that little gentle smile. And I sat at that table thinking about that little girl and thinking about the fact that she could be taken away from me any minute. And I started thinking about a dedicated, devoted and loyal wife, who was over there asleep. And she could be taken from me, or I could be taken from her. And I got to the point that I couldn’t take it any longer. I was weak. Something said to me, you can’t call on Daddy now, he’s up in Atlanta a hundred and seventy-five miles away. You can’t even call on Mama now. You’ve got to call on that something in that person that your Daddy used to tell you about, that power that can make a way out of no way. And I discovered then that religion had to become real to me, and I had to know God for myself. And I bowed down over that cup of coffee. I never will forget it … I prayed a prayer, and I prayed out loud that night. I said, ‘Lord, I’m down here trying to do what’s right. I think I’m right. I think the cause that we represent is right. But Lord, I must confess that I’m weak now. I’m faltering. I’m losing my courage. And I can’t let the people see me like this because if they see me weak and losing my courage, they will begin to get weak.’”

But King says that as he prayed, he felt God telling him to stand up for justice, and reassuring him that his cause was right. Through his faith, King was able to press forward despite his nerves and fear.

To me, King becomes more impressive the more we understand him as a full and complicated human being with emotions and frailties. When I first learned about King’s infamous moral weaknesses, of infidelity and academic dishonesty, it didn’t spoil my image of him. Instead, it made him an even more fascinating character; not more admirable, to be sure, but more relatable. And it emphasized the challenge that King’s life poses to everyone that comes after him: if he, an ordinary flawed human being, albeit one with extraordinary intellectual and rhetorical gifts, could muster the courage and energy to take on segregation, disenfranchisement, poverty, and the Vietnam War, and do so knowing it would likely cost him his life, what excuse do the rest of us have for not doing more against the injustices of our time? The less we view Martin Luther King as some Christ-like aberration, the more difficult it is to escape the tough questions he raised about what an ordinary person’s obligations are in a world of violence and cruelty.

King was a radical, then. He didn’t just wish for the integration of schools, but for universal human equality and an end to violence and conflict. But just as importantly, King was a person. And the more we appreciate King the human, rather than King the icon, the more powerfully his beliefs and actions should trouble our own consciences.