I Don’t Care How Good His Paintings Are, He Still Belongs In Prison

George W. Bush committed an international crime that killed hundreds of thousands of people.

Critics from the New Yorker and the New York Times agree: George W. Bush may have been an inept head of state, but he is a more than capable artist. In his review of Bush’s new book Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors (Crown, $35.00), New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl says Bush’s paintings are of “astonishingly high” quality, and his “honestly observed” portraits of wounded veterans are “surprisingly likable.” Jonathan Alter, in a review titled “Bush Nostalgia Is Overrated, but His Book of Paintings Is Not,” agrees: Bush is “an evocative and surprisingly adept artist.” Alter says that while he used to think the Iraq War was “the right war with the wrong commander in chief,” he now thinks that it was the “wrong war” but with “the right commander in chief, at least for the noble if narrow purpose of creatively honoring veterans through art.”

Alter and Schjeldahl have roughly the same take on Bush: he is a decent person who made some dreadful mistakes. Schjeldahl says that while Bush “made, or haplessly fronted for, some execrable decisions…hating him took conscious effort.” Alter says that while the Iraq War was a “colossal error” and Bush “has little to show for his dream of democratizing the Middle East,” there is a certain appeal to Bush’s “charming family, warm relationship with the Obamas, and welcome defense of the press,” and his paintings of veterans constitute a “message of love” and a “step toward bridging the civilian-military divide.” Alter and Schjeldahl both see the new book as a form of atonement. Schjeldahl says that with his “never-doubted sincerity and humility,” Bush “obliviously made murderous errors [and] now obliviously atones for them.” Alter says that Bush is “doing penance,” and that the book testifies to “our genuine, bipartisan determination to do it better this time—to support healing in all of its forms.”

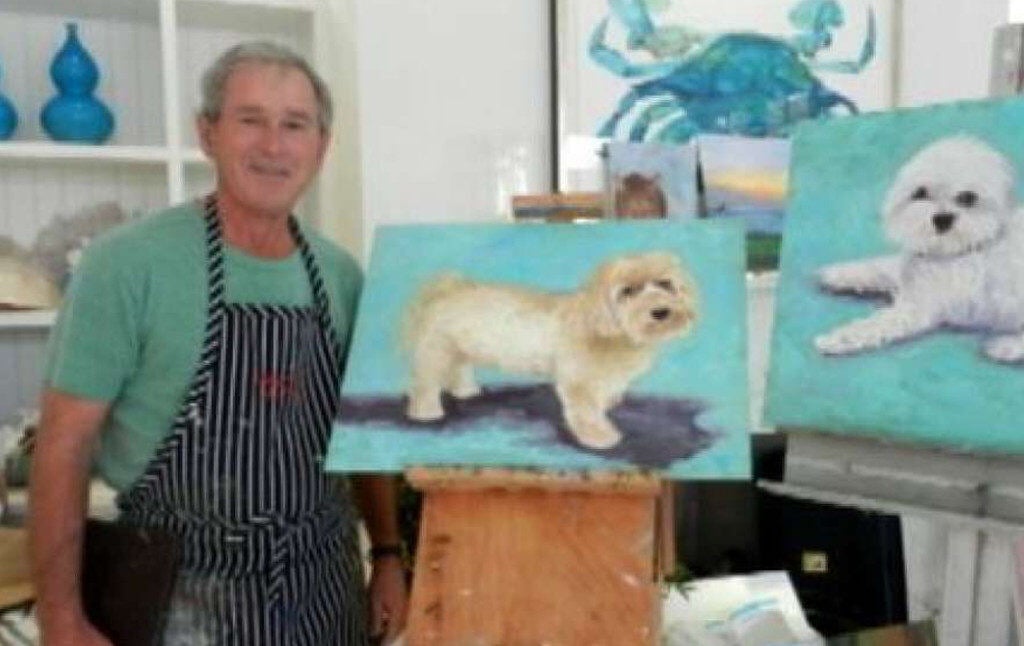

This view of Bush as a “likable and sincere man who blundered catastrophically” seems to be increasingly popular among some American liberals. They are horrified by Donald Trump, and Bush is beginning to seem vastly preferable by comparison. If we must have Republicans, let them be Bushes, since Bush at least seems good at heart while Trump is a sexual predator. Jonathan Alter insists he is not becoming nostalgic, but his gauzy tributes to Bush’s “love” and “warmth” fully endorse the idea of Bush’s essential goodness. Now that Bush spends his time painting puppies and soldiers, having mishaps with ponchos and joking about it on Ellen, more and more people may be tempted to wonder why anyone could ever have hated the guy.

Nostalgia takes root easily, because history is easy to forget. But in Bush’s case, the history is easily accessible and extremely well-documented. George W. Bush did not make a simple miscalculation or error. He deliberately perpetrated a war crime, intentionally misleading the public in order to do so, and showed callous indifference to the suffering that would obviously result. His government oversaw a regime of brutal torture and indefinite detention, violating every conceivable standard for the humane treatment of prisoners. And far from trying to “atone,” Bush has consistently misrepresented history, reacting angrily and defensively to those who confront him with the truth. In a just world, he would be painting from a prison cell. And through Alter and Schjeldahl’s effort to impute to Bush a repentance and sensitivity that he does not actually possess, they fabricate history and erase the sufferings of Bush’s victims.

First, it’s important to be clear what Bush actually did. There is a key number missing from both Alter and Schjeldahl’s reviews: 500,000, the sum total of Iraqi civilians who perished as a result of the U.S. war there. (That’s a conservative estimate, and stops in 2011.) Nearly 200,000 are confirmed to have died violently, blown to pieces by coalition air strikes or suicide bombers, shot by soldiers or insurgents. Others died as a result of the disappearance of medical care, with doctors fleeing the country by the score as their colleagues were killed or abducted. Childhood mortality and infant mortality shot up, as well as malnutrition and starvation, and toxins introduced by American bombardment led to “congenital malformations, sterility, and infertility.” There was mass displacement, by the millions. An entire “generation of orphans” was created, with hundreds of thousands of children losing parents and wandering the streets homeless. The country’s core infrastructure collapsed, and centuries-old cultural institutions were destroyed, with libraries and museums looted, and the university system “decimated” as professors were assassinated. For years and years, suicide bombings became a regular feature of life in Baghdad, and for every violent death, scores more people were left injured or traumatized for life. (Yet in the entire country, there were less than 200 social workers and psychiatrists put together to tend to people’s psychological issues.) Parts of the country became a hell on earth; in 2007 the Red Cross said that there were “mothers appealing for someone to pick up the bodies on the street so their children will be spared the horror of looking at them on their way to school.” The amount of death, misery, suffering, and trauma is almost inconceivable.

These were the human consequences of the Iraq War for the country’s population. They generally go unmentioned in the sympathetic reviews of George W. Bush’s artwork. Perhaps that’s because, if we dwell on them, it becomes somewhat harder to appreciate Bush’s impressive use of line, color, and shape. If you begin to think about Iraq as a physical place full of actual people, many of whom have watched their children die in front of them, Bush’s art begins to seem ghoulish and perverse rather than sensitive and accomplished. There is a reason Schjeldahl and Alter do not spend even a moment discussing the war’s consequences for Iraqis. Doing so requires taking stock of an unimaginable series of horrors, one that makes Bush’s colorful brushwork and daytime-TV bantering seem more sickening than endearing.

But perhaps, we might say, it is unfair to linger on the subject of the war’s human toll. All war, after all, is hell. We must base our judgment of Bush’s character not on the ultimate consequences of his decisions, but on the nature of the decisions themselves. After all, Schjeldahl and Alter do not deny that the Iraq War was calamitous, with Alter calling it one of “the greatest disasters in American history,” a “historic folly” with “horrific consequences,” and Schjeldahl using that curious phrase “murderous error.” It’s true that both obscure reality by using vague descriptors like “disaster” rather than acknowledging what the invasion meant for the people on whom it was inflicted. But their point is that Bush meant well, even though he may have accidentally ended up causing the birth of ISIS and plunging the people of Iraq into an unending nightmare.

Viewing Bush as inept rather than malicious means rejecting the view that he “lied us into war.” If we accept Jonathan Alter’s perspective, it was not that Bush told the American people that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction when he knew that it did not. Rather, Bush misjudged the situation, relying too hastily and carelessly on poor intelligence, and planning the war incompetently. The war was a “folly,” a bad idea poorly executed, but not an intentional act of deceit or criminality.

This view is persuasive because it’s partially correct. Bush did not “lie that there were weapons of mass destruction,” and it’s unfortunate that anti-war activists have often suggested that this was the case. Bush claims, quite plausibly, that he believed that Iraq possessed WMDs, and there is no evidence to suggest that he didn’t believe this. That supports the “mistake” view, because a lie is an intentional false statement, and Bush may have believed he was making a true statement, thus being mistaken rather than lying.

But the debate over whether Bush lied about WMDs misstates what the actual lie was. It was not when Bush said “the Iraq regime continues to possess and conceal some of the most lethal weapons ever devised” that he lied to the American people. Rather, it was when he said Iraq posed a “threat” and that by invading it the United States was “assuring its own national security.” Bush could not have reasonably believed that the creaking, isolated Saddam regime posed the kind of threat to the United States that he said it did. WMDs or not, there was nothing credible to suggest this. He therefore lied to the American people, insisting that they were under a threat that they were not actually under. He did so in order to create a pretext for a war he had long been intent on waging.

This is not to say that Bush’s insistence that Saddam Hussein had WMDs was sincere. It may or may not have been. The point is not that Bush knew there weren’t WMDs in Iraq, but that he didn’t care whether there were or not. This is the difference between a lie and bullshit: a lie is saying something you know to be untrue, bullshit is saying something without caring to find out if it’s true. The former highest-ranking CIA officer in Europe told 60 Minutes that the Bush White House intentionally ignored evidence contradicting the idea that Saddam had WMDs. According to the officer, when intelligence was provided that contradicted the WMD story, the White House told the officer that “this isn’t about intel anymore. This is about regime change,” from which he concluded that “the war in Iraq was coming and they were looking for intelligence to fit into the policy.” It’s not, then, that Bush knew there were no WMDs. It’s that he kept himself from finding out whether there were WMDs, because he was determined to go to war.

The idea that Saddam posed a threat to the United States was laughable from the start. The WMDs that he supposedly possessed were not nuclear weapons, but chemical and biological ones. WMD is a catch-all category, but the distinction is important; mustard gas is horrific, but it is not a “suitcase nuke.” Bashar al-Assad, for example, possesses chemical weapons, but does not pose a threat to the U.S. mainland. (To Syrians, yes. To New Yorkers, no.) In fact, according to former Saddam aide Tariq Aziz, “Saddam did not consider the United States a natural adversary, as he did Iran and Israel, and he hoped that Iraq might again enjoy improved relations with the United States.” Furthermore, by the time of the U.S. invasion, Saddam “had turned over the day-to-day running of the Iraqi government to his aides and was spending most of his time writing a novel.” There was no credible reason to believe, even if Saddam possessed certain categories of weapons prohibited by international treaty, that he was an active threat to the people of the United States. Bush’s pre-war speeches used terrifying rhetoric to leap from the premise that Saddam was a monstrous dictator to the conclusion that Americans needed to be scared. That was simple deceit.

In fact, Bush had long been committed to removing Saddam, and was searching for a plausible justification. Just “hours after the 9/11 attacks,” Donald Rumsfeld and the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff were pondering whether they could “hit Saddam at the same time” as Osama bin Laden as part of a strategy to “move swiftly, go massive.” In November of 2001, Rumsfeld and Tommy Franks began plotting the “decapitation” of the Iraqi government, pondering various pretexts for “how [to] start” the war. Possibilities included “US discovers Saddam connection to Sept. 11 attack or to anthrax attacks?” and “Dispute over WMD inspections?” Worried that they wouldn’t find any hard evidence against Saddam, Bush even thought of painting a reconnaissance aircraft in U.N. colors and flying it over Iraqi airspace, goading Saddam into shooting it down and thereby justifying a war. Bush “made it clear” to Tony Blair that “the U.S. intended to invade… even if UN inspectors found no evidence of a banned Iraqi weapons program.”

Thus Bush’s lie was not that there were weapons of mass destruction. The lie was that the war was about weapons of mass destruction. The war was about removing Saddam Hussein from power, and asserting American dominance in the Middle East and the world. Yes, that was partially to do with oil (“People say we’re not fighting for oil. Of course we are… We’re not there for figs.” said former Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel, while Bush CENTCOM commander John Abizaid admitted “Of course it’s about oil, we can’t really deny that”). But the key point is that Bush detested Saddam and was determined to show he could get rid of him; according to those who attended National Security Council meetings, the administration wanted to “make an example of Hussein” to teach a lesson to those who would “flout the authority of the United States.” “Regime change” was the goal from the start, with “weapons of mass destruction” and “bringing democracy” just convenient pieces of rhetoric.

Nor was the war about the well-being of the people of Iraq. Jonathan Alter says that Bush had a “dream of democratizing the Middle East” but simply botched it; Bush’s story is almost that of a romantic utopian and tragic hero, undone by his hubris in just wanting to share democracy too much. In reality, the Bush White House showed zero interest in the welfare of Iraqis. Bush had been warned that invading the country would lead to a bloodbath; he ignored the warning, because he didn’t care. The typical line is that the occupation was “mishandled,” but this implies that Bush tried to handle it well. In fact, as Patrick Cockburn’s The Occupation and Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s Imperial Life in The Emerald City show, American officials were proudly ignorant of the Iraqi people’s needs and desires. Decisions were made in accordance with U.S. domestic political considerations rather than concern for the safety and prosperity of Iraq. Bush appointed totally inexperienced Republican Party ideologues to oversee the rebuilding effort, rather than actual experts, because the administration was more committed to maintaining neoconservative orthodoxies than actually trying to figure out how to keep the country from self-destructing. When Bush gave Paul Bremer his criteria for who should be the next Iraqi leader, he was emphatic that he wanted someone who would “stand up and thank the American people for their sacrifice in liberating Iraq.”

As the situation in Iraq deteriorated into exactly the kind of sectarian violence that the White House had been warned it would, the Bush administration tried to hide the scale of the disaster. Patrick Cockburn reported that while Bush told Congress that fourteen out of eighteen Iraqi provinces “are completely safe,” this was “entirely untrue” and anyone who had gone to these provinces to try and prove it would have immediately been kidnapped or killed. In tallies of body counts, “U.S. officials excluded scores of people killed in car bombings and mortar attacks from tabulations measuring the results of a drive to reduce violence in Baghdad.” Furthermore, according to the Guardian “U.S. authorities failed to investigate hundreds of reports of abuse, torture, rape and even murder by Iraqi police and soldiers” because they had “a formal policy of ignoring such allegations.” And the Bush administration silently presided over atrocities committed by both U.S. troops (who killed almost 700 civilians for coming too close to checkpoints, including pregnant women and the mentally ill) and hired contractors (in 2005 an American military unit observed as Blackwater mercenaries “shot up a civilian vehicle” killing a father and wounding his wife and daughter).

Then, of course, there was torture and indefinite detention, both of which were authorized at the highest levels. Bush’s CIA disappeared countless people to “black sites” to be tortured, and while the Bush administration duplicitously portrayed the horrific abuses at Abu Ghraib as isolated incidents, the administration was actually deliberately crafting its interrogation practices around torture and attempting to find legal loopholes to justify it. Philippe Sands reported that the White House tried to pin responsibility for torture on “interrogators on the ground,” a “false” explanation that ignored the “actions taken at the very highest levels of the administration” approving 18 new “enhanced interrogation” techniques, “all of which went against long-standing U.S. military practice as presented in the Army Field Manual.” Notes from 20-hour interrogations reveal the unimaginable psychological distress undergone by detainees:

Detainee began to cry. Visibly shaken. Very emotional. Detainee cried. Disturbed. Detainee began to cry. Detainee bit the IV tube completely in two. Started moaning. Uncomfortable. Moaning. Began crying hard spontaneously. Crying and praying. Very agitated. Yelled. Agitated and violent. Detainee spat. Detainee proclaimed his innocence. Whining. Dizzy. Forgetting things. Angry. Upset. Yelled for Allah. Urinated on himself. Began to cry. Asked God for forgiveness. Cried. Cried. Became violent. Began to cry. Broke down and cried. Began to pray and openly cried. Cried out to Allah several times. Trembled uncontrollably.

Indeed, the U.S. Senate Select Intelligence Committee’s report on CIA interrogation tactics concluded that they were “brutal and far worse than the CIA represented to policymakers.” They included “slamming detainees into walls,” “telling detainees they would never leave alive,” “Threats to harm the children of a detainee, threats to sexually abuse the mother of a detainee, threats to cut a detainee’s mother’s throat,” waterboardings that sometimes “evolved into a series of near drownings,” and the terrifyingly clench-inducing “involuntary rectal feedings.” Sometimes they would deprive detainees of all heat (which “likely contributed to the death of a detainee”) or perform what was known as a “rough takedown,” a procedure by which “five CIA officers would scream at a detainee, drag him outside of his cell, cut his clothes off, and secure him with Mylar tape. The detainee would then be hooded and dragged up and down a long corridor while being slapped and punched.” All of that is separate from the outrage of indefinite detention in itself, which kept people in cages for years upon years without ever being able to contest the charges against them. At Guantanamo Bay, detainees became “so depressed, so despondent, that they had no longer had an appetite and stopped eating to the point where they had to be force-fed with a tube that is inserted through their nose.” Their mental and emotional conditions would deteriorate until they were reduced to a childlike babbling, and they frequently attempted self-harm and suicide. The Bush administration even arrested the Muslim chaplain at Guantanamo Bay, U.S. Army Captain James Yee, throwing him in leg irons, threatening him with death, and keeping him in solitary confinement for 76 days after he criticized military practices.

Thus President Bush was not a good-hearted dreamer. He was a rabid ideologue who would spew any amount of lies or B.S. in order to achieve his favored goal of deposing Saddam Hussein, and who oversaw serious human rights violations without displaying an ounce of compunction or ambivalence. There was no “mistake.” Bush didn’t “oops-a-daisy” his way into Iraq. He had a goal, and he fulfilled it, without consideration for those who would suffer as a result.

It should be mentioned that most of this was not just immoral. It was illegal. The Bush Doctrine explicitly claimed the right to launch a preemptive war against a party that had not actually attacked the United States, a violation of the core Nuremberg principle that “to initiate a war of aggression…is not only an international crime; it is the supreme international crime, differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole.” Multiple independent inquiries have criticized the flimsy legal justifications for the war. Former U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan openly declared the war illegal, and even Tony Blair’s former Deputy Prime Minister concurred. In fact, it’s hard to see how the Iraq War could be anything but criminal, since no country—even if it gathers a “coalition of the willing”—is permitted to simply depose a head of state at will. The Iraq War made the Nuremberg Laws even more empty and selective than they have always been, and Bush’s escape from international justice delegitimizes all other war crimes prosecutions. A core aspect of the rule of law is that it applies equally to all, and if the United States is free to do as it pleases regardless of its international legal obligations, it is unclear what respect anybody should hold for the law.

George W. Bush may therefore be a fine painter. But he is a criminal. And when media figures try to redeem him, or portray him as lovable-but-flawed, they ignore the actual record. In fact, Bush has not even made any suggestion that he is trying to “atone” for a great crime, as liberal pundits have suggested he is. On the contrary, he has consistently defended his decision-making, and the illegal doctrine he espoused. He even wrote an entire book of self-justifications. Bush is not a haunted man. And since any good person, if he had Bush’s record, would be haunted, Bush is not a good person. Kanye West had Bush completely right. He simply does not think very much about the lives of people darker than himself. That sounds like an extreme judgment, but it’s true. If he cared about them, he wouldn’t have put them in cages. George Bush may love his grandchildren, he may paint with verve and soul. But he does not care about black or brown people.

It’s therefore exasperating to see liberals like Alter and Schjeldahl offer glowing assessments of Bush’s book of art, and portray him as soulful and caring. Schjeldahl says that Bush is so likable that hating him “takes conscious effort.” But it only takes conscious effort if you don’t think about the lives of Iraqis. If you do think about the lives of Iraqis, then hating him not only does not take conscious effort, but it is automatic. Anyone who truly appreciates the scale of what Bush inflicted on the world will feel rage course through their body whenever they hear his voice, or see him holding up a paintbrush, with that perpetual simpering grin on his face.

Alter and Schjeldahl are not alone in being captivated by Bush the artiste. The Washington Post’s art critic concluded that “the former president is more humble and curious than the Swaggering President Bush he enacted while in office [and] his curiosity about art is not only genuine but relatively sophisticated.” This may be the beginning of a critical consensus. But it says something disturbing about our media that a man can cause 500,000 deaths and then have his paintings flatteringly profiled, with the deaths unmentioned. George W. Bush intentionally offered false justifications for a war, destroyed an entire country, and committed an international crime. He tortured people, sometimes to death.

But would you look at those brushstrokes? And have you seen the little doggies?