MLMs prey on the vulnerable, pitching promises as much as their products—and they're as American as apple pie.

The direct sales industry, of which MLMs are a part, has been around for a while. In the United States, it began with Yankee Peddlers, a staple of rural life from the colonial period to the mid-1800s. At the time, when the country was mostly made up of rural communities, the peddlers sold goods and brought information that would otherwise have been hard to come by. But they didn’t have the best reputations. Known as pushy and bawdy, the travelling salesmen were also challenged by the widespread adoption of railways and retail stores.

In the early 1900s, though, some manufacturers became unhappy with this development. In large stores, where consumers had a larger variety of products to choose from, they felt that their products weren’t getting enough attention. Some began hiring door-to-door salesmen again so they could more effectively push their products and theirs alone.

Scientific management and sales techniques were in their infancy at the time, encouraging the use of memorized scripts and catchy buzzwords. This was particularly successful in selling novel household appliances like vacuums and radios, appealing to budding middle-class consumerism. But for everyday products, it didn’t cut it.

Enter David McConnell, founder of the California Perfume Company. As a former peddler himself, he knew the negative reputation they had. But he also knew the upsides to direct sales. In rural, tight-knit communities especially, a peddler could make the personal appeals and connections a shopkeeper couldn’t. So McConnell took to a new strategy. He would hire more women, who were a minority in the trade, to help peddlers’ image problem. And he would scout and train locals instead of hiring outside professional salesmen. These locals would be more adept to the wants of their specific communities and could tap into their social networks for sales.

It worked. Personal connections and tailored pitches brought great success to the direct sellers that took advantage of them. Famed businesswoman Madame CJ Walker, the first female self-made millionaire in the United States, was one; she catered to the underserved African-American beauty market, creating specialized hair and cosmetic products. Her company was one of the first to adopt a more MLM-styled direct sales model, as her salespeople were given big bonuses to recruit other sellers. These weren’t just monetary incentives, either—they could be diamonds, or even low-cost mortgages.

In these early days of direct sales, companies usually took on the responsibility and costs of training salespeople themselves. By the end of the 1920s, direct sales were beginning to eclipse retail sales of certain products, and demand was relatively high, so salespeople could make a tidy profit through either commissions or resale.

Then came the Great Depression. But this didn’t stop the rise of direct sales. In fact, with more people losing work or needing supplemental income, direct selling was an appealing job prospect. This was particularly advantageous for companies that used the model in which salespeople bought products for resale. They were insulated from fluctuations in consumer demand, as new salespeople would dependably buy products even if they couldn’t sell them to consumers.

Sweeping New Deal reforms presented an issue for the direct sales industry, though. The Fair Labor Standards and Social Security Acts enforced a standard minimum wage, unemployment insurance, and payroll tax requirements. This would have created huge expenses for direct selling companies with thousands of employees.

But at a 1935 industry conference, one executive made a tentative suggestion: “How about [labelling the] salesperson as an independent contractor...If we changed our form of application and specified that this man buys the merchandise from us for resale?”

This idea caught on quickly, not only in direct sales, but across many industries. Defining workers as independent contractors to skirt employment regulations was a win-win for direct selling organizations. Not only could they cut labor costs, but they could also reduce fixed costs like transportation, training, and business expenses. (Today, much of the gig economy rests on this independent contractor loophole. Even if in most respects workers could be considered full employees, misclassification is used to cut labor expenses.)

In 1939, the California Perfume Company rebranded, taking the now-household name Avon. It’s currently the second-most profitable MLM in the world. The company boasts that their founder, McConnell, was something of a proto-feminist trailblazer, offering women the opportunity to be their own bosses in an era not far removed from coverture laws. It’s more likely, though, that he was savvy to the fact that women could more effectively penetrate home markets. The MLMs that sprung up after Avon courted women for this reason too. But as direct sales companies began to prioritize recruitment over product sales, they could also use women’s socio-economic status to draw them into the pyramidal “downline” trap.

Mary Kay Cosmetics and Tupperware pioneered the “party plan” sales strategy in the 1950s, ushering in the MLM era of direct selling. Like Avon before them, they relied on saleswomen, though now they were presented with the opportunity to work from home instead of going door-to-door. They could take advantage of their pre-existing social networks to make a little extra on the side. The companies presented themselves as both empowering for women and a socially approved means for them to keep their traditional homebound duties.

The coming encroachment of the professional sphere into the personal was an extension of emerging business management strategies of the era. These promoted continuous evaluations and rankings against coworkers and total devotion to one’s work, even off the clock, as a sign of one’s worth. They also countered the more collectivist workplace sensibilities of the past.

For people in direct sales, the erosion of trust that came with monetizing personal relationships would follow suit.

In the decades since the party plan fell out of fashion, women still make up the majority of the direct sales industry. Sociologist Nicole Biggart, interviewing MLM salespeople in 1989, was given many reasons for this by her female interviewees. Women take on the majority of household labor and childcare responsibilities in addition to their paid jobs, and they liked the idea of having more flexibility, so as to balance out their work and family lives. They liked the idea of the instant “family” of salespeople they could gain, which were usually more welcoming than coworkers in a typical job. Joining an MLM also requires no qualifications, and there are few social barriers in the way of joining—some respondents noted they felt the playing field was more level than in traditional jobs, as everyone in the company was judged for the same skillset. Their sales were directly tied to promotions, unlike traditional job positions, where the process for receiving pay increases or climbing the ladder are more opaque. And they felt more self confidence, as they felt more respected and in control of their decisions than at low-paying and demanding service sector jobs.

An MLM can seem a very appealing alternative to a precarious working environment. This is doubly true for women who feel unable to take on demanding careers, either because of cultural norms (see the massive MLM involvement of religious conservatives), obligations at home, or inability to find other kinds of work.

Founded in 1959, Amway would further capitalize on the growing disillusionment with American work culture. Amway, short for “American Way”, is the largest MLM in the world today by revenue. It introduced one of the direct sales’ industry’s most influential lines of messaging: the allure of becoming an entrepreneur. Taking the flavor of Reagan-era bootstraps ideals, Amway’s advertisements focused as much on pitching the idea of becoming a businessperson as on their home products and motivational tapes. “Amway can show you how to stop whining and start living,” one advertisement read.

This condescension is a constant in MLMs. It helps keep hold of salespeople, even when they aren’t successful. There are hundreds of motivational guide books for MLM work, often preaching some variation of that Amway advertisement: there’s a “proven” system that’s worked for others, so it’s your responsibility to find success within it. All it takes is grit, perseverance, and the right attitude.

MLM coach Brian Carruthers, for example, offers some vague advice to “focus on wealth” (because otherwise you’re “repelling it away from you”) and a daily affirmation to help with that. “I am building my own financial empire using the only vehicle that enables me to do so...I am a champion, a warrior for freedom, an expert recruiter, a winning coach, a caring teammate, and a fearless leader. I am because I say I am, and today I will find the next me!” This is the same individualist ethos and meaningless phraseology that can be found in less openly ridiculous MLM messaging: whatever happens, it’s up to you and you alone to reach success with an MLM. If you don’t, it’s a personal failing, not the company’s.

It was Amway that took MLM branding to the level of ideology, claiming not only to provide financial security, but also empowerment in a time of vulnerability and flux. It managed to avoid the fate of Koskot—while it was slapped on the wrist in 1979 for price fixing, it wasn’t branded a pyramid scheme. This was because the company made sure to impose certain rules on its distributors: they had to sell 70 percent of their monthly purchases at wholesale or retail, which would supposedly prevent them over-purchasing from Amway; they also had to make sales to at least 10 customers per month, which was intended to prevent distributors from solely focusing on recruitment and creating pyramidal “downlines.” Later MLMs would adopt rules like these to ensure they wouldn’t be taken down by the Federal Trade Commission. Many, though, have loopholes that enable internal consumption to be considered a portion of sales, including Amway.

The concepts of freedom and independence became central to MLM recruiting tactics. Amway would contrast the image of an “organization man,” dull and meek, to the limitless potential and vitality of an Amway distributor. Freedom from alienation—a lack of fulfillment and connection to one’s work—was also a large selling point. Amway’s motivational tapes emphasized an overall change of mentality as well as a shift to independent sales, using buzzwords like “dream building,” “positive programming,” “sensebreaking,” and “sensegiving.” Much like the pop-psych concept of “emotional intelligence,” they required suppression of frustrations through constant self-reflection, or rather, self-critique. They prevent acknowledging external sources of emotional fatigue, too.

Shifting criticism inwards helps MLMers ignore the glaring contradictions of multi-level marketing. What’s advertised as a flexible “side hustle” really requires the surrendering of some personal freedoms and hours of extra time. You must either take part in an exploitative downline, trying to sell enough inventory to turn a profit, or attempt to recruit others and form your own (the main way to reach financial success through an MLM). By definition, MLMs have a rigid hierarchy of “levels,” with those who recruited you often taking a cut of your profits from sales.

In the 1970s, financial stability generally had a larger appeal than the entrepreneurial image. The loss of many stable manufacturing sector jobs and economic downturn made people flock to Amway, in the hopes that they could secure a steady income. Amway saw this and adjusted their messaging accordingly: “In these uncertain times, many jobs are threatened by uncontrollable events…[join Amway] now and you’ll look to the future confidently through job security you build for yourself,” an advertisement printed in the 1970s said.

Of course, some MLMs have faced repercussions over the years for not living up to their big promises. Recently, in 2013, the FTC declared that Global Information Network, Ltd. was an illegal pyramid scheme using a test developed in the 1973 Koskot case. In 2019, they also branded Neora and Advocare pyramid schemes, banning the latter from multi-level marketing. But the most publicized recent case was in 2016 against the nutritional supplement MLM Herbalife.

Herbalife is no stranger to scandal. Founded in the 1980s, it carved out a niche in “natural” remedies. At the time, growing supplement and nutrition industries could prey on burgeoning fears of processed foods and the need to look for treatment outside of typical healthcare, as the 1980s were the beginning of the dramatic upswing in American medical prices. Like many MLMs, Herbalife used gimmicky, possibly healthful but likely useless “miracle” ingredients to justify products’ high prices relative to retail (think mink oil). But theirs were a little more extreme. Some of their diet products contained dangerous amounts of laxatives, caffeine, and the deadly, now-outlawed ephedra. They made claims that their herbal supplements could treat or cure cancer and diabetes. In a shouting match during his chaotic 1985 Senate hearing, Herbalife founder Mark Hughes even fessed up to the fact that 40 percent of his consumers suffered adverse effects from their products. But FDA officials at the time said it required additional congressional authority to regulate diet products like Herbalife’s.

Luckily for Herbalife, the FDA wasn’t granted this congressional authority. They had a strong ally in Senator Orrin Hatch of Utah. The state was and is a hotbed of MLM activity, so naturally, he intervened to assist them. An investigation into Herbalife’s possible money laundering activities was preemptively shut down by Hatch, according to a former FDA agent. Hatch would also introduce a 1994 bill that all but eliminated FDA regulation of dietary supplements, Herbalife’s staple product.

The company has maintained quite a few high-profile supporters and public-private revolvers, including former FDA officials. This undoubtedly helped them navigate the bombshell 2016 FDA investigation, which yielded a pile of evidence suggesting compensation was based primarily on recruiting over sales and that its “nutrition clubs,” aimed mainly at Latino immigrant communities, were intentional financial traps which led to salespeople losing thousands, among other allegations.

But despite this—as well as the great discrepancies between the tiny group of top earners and the vast majority of salespeople, and the necessity of recruitment—Herbalife wasn’t branded a pyramid scheme. It was instead ordered to pay $200 million in restitution to 350,000 victims (a drop in the bucket compared to its overall earnings) and was instructed to “restructure” to reward retail sales. No executives were charged, and monitoring of the negotiated restructuring agreement doesn’t appear to be strict. Internal compliance investigations found that some Herbalife affiliates have been reporting the purchases of other affiliates’ recruits as purchases from retail customers, a roundabout way to keep downlines buying up products.

In 2020, Herbalife was charged again, this time for bribing Chinese officials for almost a decade. And again, it got away with a fine. (This arrangement was made through a deferred prosecution agreement, a deal regulators have leaned on heavily since the 2008 financial crisis, which allows for each indicted corporation to enter an individual negotiation with prosecutors. No binding precedent is set, and enforcement of punishments can vary widely.) Recent studies have also documented cases of acute liver failure, likely caused by Herbalife products, in Spain, Israel, several Latin American countries, Switzerland, Iceland, the United States, and India. But even after these rocky few years, Herbalife’s profits and share prices seem to be on the rebound.

MLMs aren’t all as big and powerful as Herbalife and Amway. But they’re all sustained by an ecosystem that’s conducive to their development. Even with a less lax FTC under Biden, the Supreme Court has stepped in to allow companies found of wrongdoing to skirt payment of monetary damages. They severely restricted the FTC’s ability to bring 13(b) actions, which were used to force Herbalife, AdvoCare, and other pyramidal MLMs to pay back their victims. The people who have been cheated and hurt largely go uncompensated.

But it’s not as though there’s no public opposition to MLMs. While Facebook and Instagram are still mainstays for MLM sales and recruiting, Youtube, Reddit, and TikTok are the opposite. Anti-MLM content gets millions of views, likes, and upvotes. The “hunbots” (referencing the “hey hun” mass-copied-and pasted messages social media recruiters use) and “girlbosses” get pitied and scorned. They’re portrayed either as victims of an MLM’s cult-like grip or mindless proponents of it.

MLM-cult comparisons are quite common, actually, both from fervent anti-MLMers and former MLMers themselves. And for good reason—there are a lot of unsettling similarities between cult control and MLM coercion techniques. NXIVM, now disbanded, was a bonafide cult-MLM hybrid. And try watching an MLM recruitment seminar or abusive team call and thinking it’s not at least a little cult-y. The cult parallels can differentiate MLMs—with their predatory nature and strange internal cultures—from the more respectable business world.

But while an MLM’s charismatic, overbearing leadership, and demands for devotion are comparable to a cult’s, they’re more cult-like in the sense that they seek out vulnerable people and subject them to a draining, rigid, competitive hierarchy. Sellers aren’t nearly as deeply devoted to their leadership or organizations as cult members are to theirs. Some distributors will move from MLM to MLM, more likely drawn to the sales model over the companies themselves. An MLM’s ideological pull seems more similar to a standard business’ “internal branding” techniques than to a cult’s. These are superficial motivational messages and careful rebranding techniques intended to create a devoted workforce, one that will internalize or “live the [brand] vision” of their employers. MLMs are much more extreme in their manipulation and atomization of workers, but that doesn’t mean non-MLM companies are in the clear.

MLMs claimed to have had a banner year for recruitment in 2020, though the industry’s public data is primarily self-reported and thus hard to verify. But given the economic turmoil and chaos we’ve been through, it’s believable that more would flock to MLMs. Direct sales industry publications indicate that Gen Z is a particularly fertile recruiting ground. Their technological prowess, “intuitive” understanding of social media and “personal branding,” and (perhaps most importantly) their chronic financial and job insecurities are cited as reasons why. Side hustles are now necessities.

These publications also note that Gen Z is attuned to social justice currents, advising MLMs to play that up in their mission statements and branding, as they had with claims of empowering women. This is an interesting choice, given MLMs’ exploitation of vulnerable groups in the United States and in poorer countries, where they now make most of their revenue. In addition to shoddy products, MLMs have exported their manipulative promises of stability.

You might’ve noticed at this point that I’ve barely mentioned MLM products themselves, besides the most dangerous ones. That’s because they’re really a negligible part of the MLM model. For sellers, sustainable income requires recruitment, embracing and reinforcing self-flagellating individualism, as well as the allure of agency and financial independence. The forces that shaped MLMs, as well as the rest of our working lives, helped create the much-maligned hunbot drones and the superficially empowered girlbosses. This isn’t to say MLMers have no agency and that we shouldn’t criticize these archetypes, but that we should know their approaches have been influenced by certain industry and system-wide ideals.

Amway founder Richard DeVos named his 1994 treatise Compassionate Capitalism. It’s a very fitting name, but in a way he didn’t intend. MLMs have always presented themselves as a friendly helping hand, giving you a leg up in a ruthless capitalist system. But of course, that underlying system remains, and even worsens, under an MLM. They’re a reproduction in miniature of some of its worst impulses. And they will continue to pop up, so long as that system lacks the regulatory framework or the political will to constrain them.

This piece originally appeared in a 2021 print edition of Current Affairs Magazine.

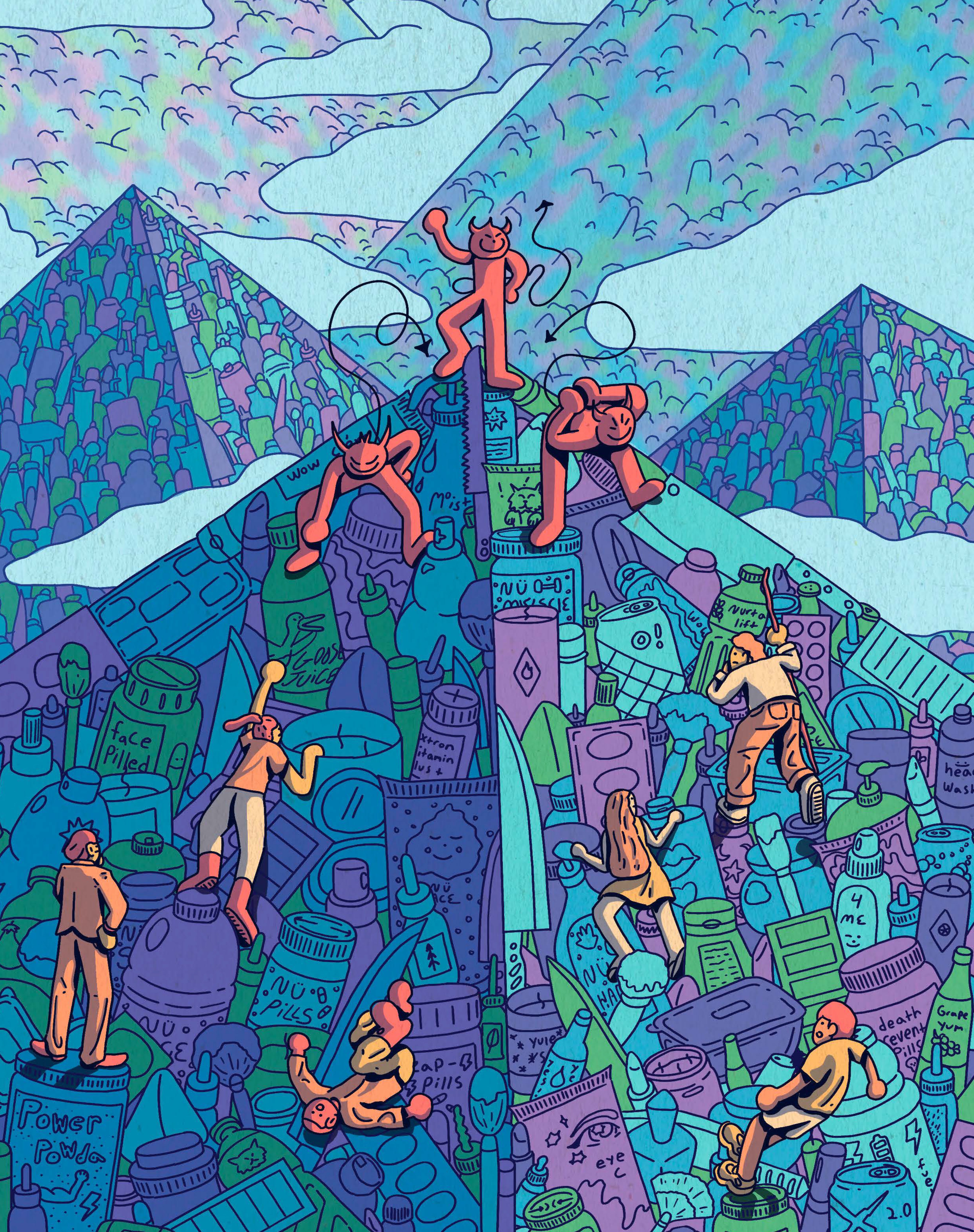

Cover art by Patrick Edell.

.png?width=352&name=r-cohen%20(1).png)