The Current Israel-Palestine Crisis Was Entirely Avoidable

Political scientist Jerome Slater on how the refusal to grant Palestine a state set the region on the course for disaster…

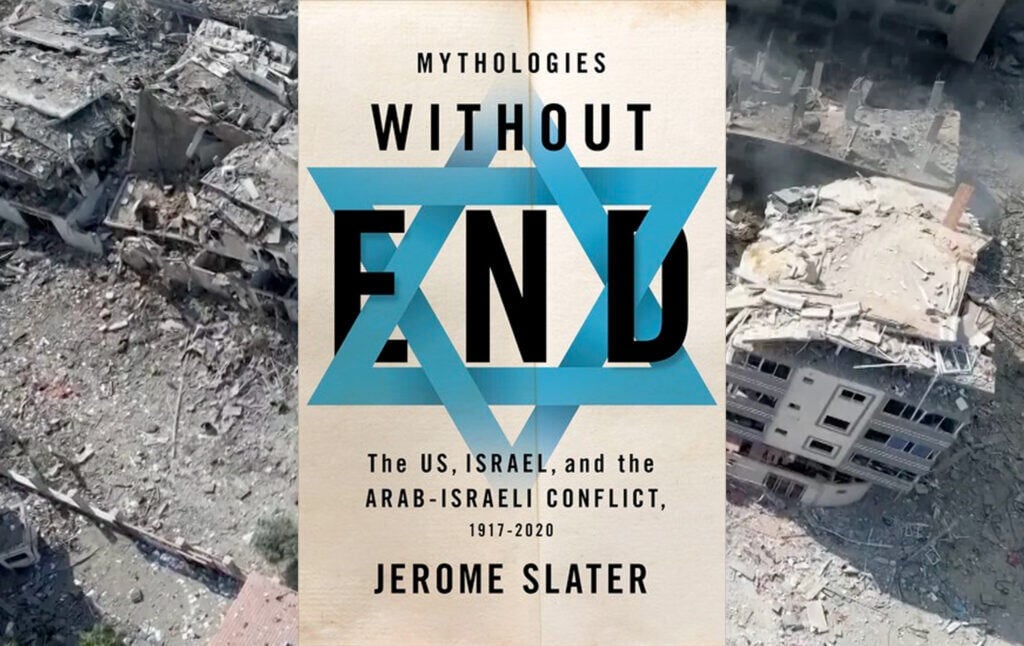

Political scientist Jerome Slater is the author of one of the best one-volume summaries of the background of the Israel-Palestine conflict, Mythologies Without End: The US, Israel, and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1917-2020 (Oxford University Press). Slater argues in the book that the possibilities for a peaceful resolution to the conflict were consistently eroded by Israel’s refusal to withdraw to its legal borders and successive Israeli leaders’ staunch opposition to a Palestinian state. Slater’s exhaustively documented but accessible work also predicted that Israel’s policies toward Palestine were creating the conditions for a “disaster.” Three years later, Slater’s predictions have tragically come true. He recently joined Current Affairs editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson to explain the background to the conflict.

Robinson

Your book was published a few years ago now, but I was rereading it, and you make a couple of side comments that are rather prescient in retrospect. From your preface, you write:

“I’ve become convinced that Israel, with essentially blind US Jewish and government support, is well along the road to both a moral and security disaster.”

And you write that Israel needed to come to terms with historical truth—which is what much of your book is about—to perhaps, even literally, “save itself from an attack” by fanatical terrorists.

Looking back on those words, why was it that back in 2020, you thought that Israel was well along the road to a security disaster?

Slater

Israelis and others were predicting that not in 2020, but in some cases in 1947 and afterward. The reason for a moral and security disaster is that Israel has been occupying and repressing the Palestinians from the very outset of the creation of Israel, or even before its creation, in seizing territory and an occupying the West Bank and so on. There have been, as you know, a number of wars which have ended in Israeli victories, but which have only created the context for future wars.

So, if you regard, as I do, the root cause of this conflict not as an unending fanaticism of Arabs to destroy Israel, but rather the Israeli seizure of territory, the creation of settlements, and simply, in short, the occupation and repression of the Palestinians, it was perfectly predictable that, sooner or later, it was going to break out in a major conflict. And of course, there have been major conflicts in the past, but they all have the same root cause.

Robinson

In fact, towards the end of the book, in your summary and conclusion sections, you have a number of quite extraordinary quotes of warnings from former IDF chiefs of staff and former Mossad directors and generals, often quite hawkish people who said they prioritized Israel’s national security [and were critical of Israel’s policy toward Palestinians].

There’s an incredible quote you have from an admiral saying, “It will be a catastrophe if we win.” That’s an interesting thing to say. Why would it be a “catastrophe if we win”?

Slater

If “we win,” it means that we’ve just created more resentment and hatred, and it’s going to come back against us in the future. I’ll read you a few of the quotes. There are a number of high officials who said specifically that we can and should negotiate with Hamas. Now you have this incredible fanaticism, and we’ll get to that later on. But earlier, there were Hamas leaders who were in some cases hinting—in some cases more than just hinting—that they recognized that they were not going to be able to defeat Israel, they’re not going to be able to achieve their maximum goal, and then they reluctantly but nonetheless came to the conclusion that they needed a settlement. And there were Israeli top security officials—heads of Mossad or Shin Bet—who said, this is almost too good to be true, we must act on this and start negotiations with Hamas.

But the all Israeli prime ministers absolutely ignored and shut down a number of efforts that were being made, including by journalists and others, to start a dialogue between Hamas and Israel. So, even in the case of Hamas, let alone in the largest sense of achieving a two-state solution, you have a phenomenon of top leaders making these kinds of arguments.

Robinson

Your book is, in many ways, the story of a lot of frustrating, tragic missed opportunities. The phrase of “missed opportunities” is kind of infamous in the context of this conflict. Because [Israeli diplomat] Abba Eban said that “[The Arabs] never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity.” But in fact, what your book does, in many ways, is highlight opportunities that Israel had if just a few key concessions has been made to the Palestinians, and you enumerate them.

What are the concessions that you think successive Israeli governments refused to make, that if they had been made could have massively increased the chances that there would have been a lasting peace and avoided the current catastrophe?

Slater

The main one is withdrawing from all the territory they conquered in 1967 and allowing the Palestinians to exercise sovereignty over that, primarily the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Since the 1967 war, the main problem has been Israeli refusal to withdraw. It withdrew from some of the territories, from Sinai in the context of the peace agreement with Egypt 15 years after the end of the 1967 war, but they refused to withdraw from the West Bank. Gaza is a little more complicated. They had settlements in Gaza, and Ariel Sharon, Israel’s leading military hawk, decided when he became prime minister that the cost of hanging on to a few settlements mostly manned by Israeli fanatics was too high. So, they withdrew from Gaza, in the sense of there’s no longer any settlements on the ground in Gaza. But they control access to Gaza; they control water, electricity, and the airways. And they’ve used this control on a number of occasions, not just now, to punish Palestinian acts of terrorism. And of course, what we’re going to see now is the most devastating use of Israeli control and power over Gaza.

In the negotiations over two-state settlements, some of which appear to have come pretty close, there were other issues which had to be dealt with. Exactly what would happen to the Israeli settlers, who were already in the West Bank and in East Jerusalem? How would their water resources be divided? If Israel said, we must keep at least some of the settlements which are right on the border between Israel and the West Bank, then the Palestinians would get equivalent territory in the Negev, so on and so forth.

And of course, another big issue was that the Palestinian leaders demanded that all the refugees, down through the present who are refugees from the 1948 war, must be allowed to return to Israel. Well, by most reckonings that meant 750,000—in the 1960s, about 750,000 Palestinians would be returned to their homes in Israel. It was an impossible demand for all kinds of reasons. Their homes didn’t exist anymore, and there was no possibility that Israel, which was determined to ensure a large Jewish majority, was going to accept that. So, we know that in practice the main Palestinian leaders, particularly Arafat and the current leader Mohammad Abbas, made it clear to Israel, in some cases more than just Israel (the New York Times would have stories on it), they were prepared to accept far fewer, maybe 10-15,000 refugees. It was the principle that it bore responsibility or a large share of responsibility for the creation of the refugees in the first place.

So if Israel found some words it could live with, the numbers that would be admitted would not change the character of the Jewish state, but Israel would not consider that.

Robinson

What you’re saying, as I understand it, is that what may have looked like, and certainly was portrayed as, Palestinian intransigence and insistence upon an unrealistic demand—the full implementation of the Right of Return—was instead a situation where Palestinian leaders were more flexible than that narrative would suggest. And so that wouldn’t necessarily have been an obstacle to reaching an agreement.

Slater

That’s exactly right. You might say there were two true obstacles. Jerusalem has always been a major issue, and 10 or 15 years ago, when Ehud Olmert was prime minister, he went very far to agreeing to what would be the consensus of outsiders on how you would deal with the explosive issue of Jerusalem, which is basically to divide it into West Jerusalem, which was primarily Jewish, and East Jerusalem, which was primarily Palestinian, and also allow the Palestinians to have their capital in East Jerusalem.

The two issues that were considered to be the dealbreakers were Jerusalem and the refugees. But we know that by 10 or 15 years ago, these were no longer obstacles. Israel, or at least Ehud Olmert, was prepared to accept the division of Jerusalem, and the Palestinian negotiators were down to saying, can we have 15,000 people returned, or could it be 50,000? And Olmert himself says if we had continued to negotiations, we would have reached a compromise on that.

The real issue is that the rest of the West Bank has been increasingly occupied by Israeli settlers, most of them fanatics, who will not accept Palestinian rule and are prepared to be violent in order to prevent it. So, the real issue has been, since the outset, the occupation of Arab territory by Israel, its refusal to withdraw and allow the Palestinians to have a state.

I would highlight that: Israel will not allow the Palestinians to have a state, no matter how weak and demilitarized it would be. And in the negotiations that seem to come closer to reaching agreement, the Palestinians accepted that there would be only allowed minimal armaments sufficient to preserve internal order, but in no way powerful enough to threaten Israeli security. Security for Israel is not really the issue; it is control of the areas that they conquered in 1967.

Robinson

It certainly seems today that if security was the issue, you would not try to maintain the occupation at all costs, because as you pointed out, it actually endangers Israel’s security.

Slater

Yes. What could be more obvious than this Hamas attack, which stems from the continued Israeli de facto occupation? I agree with what you said, that occupation and repression leads to uprisings and revolutions, not just in Israel, and not just in the Middle East. It’s important to say again that this has been predicted repeatedly by high Israeli officials, including leader after leader of the two major intelligence organizations, Shin Bet and Mossad, saying not only will occupation and repression lead to an uprising, but it’s disgraceful morally.

Robinson

Yes, we haven’t even gotten to [the moral aspect.]

Slater

They say this after they’re out of power. And of course, you will find the same analyses among Israeli historians, journalists, and so on.

Robinson

I want to just read a short passage from your summary and conclusion section, which highlights what sort of tragedy this is when we think of this as an intractable conflict:

“Since 1947, Israel has fought eight to 10 wars against the Arab states and the Palestinians. None of them, probably not even the 1948 War, was unavoidable. Israel’s independence and security could have been protected had it accepted reasonable compromises on the four crucial issues: partition of the historic land of Palestine; Palestinian independence and sovereignty and the land allotted to them in the 1947 UN Partition Plan, including Arab East Jerusalem; the return of most of the territory captured in the Arab states in the various wars; and a small scale symbolic return to Israel of some 10,000 to 20,000 Palestinian refugees, or their descendants from the 1948 war. Throughout most of the conflict, all the key Arab states and the most important Palestinian leaders were or soon became willing to reach peace with Israel if it accepted these compromises. Had it done so, there would have been few if any wars, justice would have prevailed, and Israel’s independence and security would have been greatly enhanced.”

That is a history of 70 years of just an avoidable tragedy.

Slater

I stand by that. I have nothing to add to that. And, unfortunately, as we see now, I think the accuracy of that statement, I stand by it.

Robinson

I wanted to read it because you did say this a few years ago. Your book centers on mythologies. You start by saying that every nation has a narrative or stories about its history that are instilled into its citizens. You devote most of the book to examining mythologies, and you argue at various points that until mythologies are understood for what they are, it’s going to be very hard to reach a resolution to this conflict. Could you talk about what you mean by these destructive mythologies?

Slater

Certainly. The main mythology is rooted in Zionism, the argument that the Biblical God promised Palestine to the Jews and only to the Jews, and that’s based on religion. We know that for at least 2,000 years, beginning with the expulsion of the Jews by the Romans 2,000 years ago, that Palestine has been occupied by—I don’t know if the word “occupied” is too strong, but has been the home of—a variety of people, a tiny handful of them being Jewish, most of them not. And by the way, that whole biblical story is questioned in various ways by Israeli anthropologists who find very little evidence for a big kingdom of King David, et cetera.

Even if it were the case that there was Jewish control of most of Palestine 2,000 years ago, from which they were driven out, that doesn’t mean that they can go back again. If that were a general principle, it would have to apply globally, that all people who at one time or another controlled territory must have it given it back. So, we would have to give back most of the United States to begin with, and so on. It’s hard to be exact about this, but after some reasonable period of time, a new reality—a moral and political reality—emerges. Of course, land and territory in this world, unfortunately, is constantly changing hands by violence. After a while, there’s a new status quo.

So, the Israelis have never been willing to agree to that; they refuse to even recognize that the Palestinians have a right to a state of their own. [Israeli prime minister] Golda Meir used to say there’s no such thing as Palestinians, and so on.

Robinson

I think you go through all the different arguments for Zionism, and you say that all the Zionist arguments for a creation of a Jewish state in Palestine, and only in Palestine, were unconvincing, save the argument of existential necessity. That is to say, you couldn’t really argue that there was a right to establish a Jewish state and expel all the Palestinians, but you might be able to argue that in the aftermath of the Holocaust there was a just claim to establish Israel, and in fact, you say that might make the case strong. But you point out that, “a grave injustice to the Palestinians was unavoidable.” Is that to say that, from the outset, the implementation of Zionism, the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine, necessarily involved a terrible injustice to the people who already lived there?

Slater

Actually, I don’t think so. Firstly, let me say this: I think that, although there are many arguments for Zionism based on alleged biblical history—based on non-biblical history—and on the idea that the Jews and only the Jews must always rule Palestine, all of those arguments are entirely unconvincing.

There’s only one argument that’s convincing: it’s both necessary and sufficient that the Jews needed the state of their own. The history of murderous antisemitism which preceded the Holocaust, but certainly in the wake of it, made the need for a Jewish state imperative and morally right. And not only that, I would say that I still believe that the Jews need a state of our own because you can never be sure when murderous antisemitism is going to reappear.

However, if you go back to the United Nations creation of Israel, Israel was given some part of ancient Palestine and the Arab states—unspecified who they would be—would be given the rest of historic Palestine. In my view, the Israelis should have accepted that. And had they accepted that and stopped expanding, there might well have been a permanent peace imposed by the United Nations. But Israel immediately set out to conquer large parts of Palestine, which had been allocated to the Arabs. The first expansion took place almost immediately. But then you have the 1956 and 1967 wars where Israel captured large parts of Syrian, Jordanian, and Egyptian territory, most of which they refused to give back. So, you have a steady expansion of Israeli control over areas and a refusal to withdraw from at least some part of it so that there could be a viable Palestinian state.

Robinson

Many people may have heard it the opposite way to the way that you just described. One of the mythologies that you’re dealing with in the book is the idea that it was the Arabs who refused to accept the UN Partition Plan and immediately went to war against Israel, and refused to accept the creation of a Jewish state from the outset. So, why is that slightly backwards?

Slater

It’s slightly backwards because the myth is that the Arabs refused to accept the partition, but the Jews did, and therefore, everything that happened afterward was supposedly ours. Even if that were true, it wouldn’t mean that 75 years later it’s only the Arabs who are an obstacle to peace. But at the time—this is well documented, it’s not open to question—David Ben-Gurion, the unquestioned leader of the Zionists and early Israelis, said explicitly that we have to accept a small slice of Palestine because we have no choice, we’re not strong enough at this point to do anything about it. So, let’s go ahead and agree to the UN partition, and in time, we will regain the rest of Palestine. Our armaments will be built up—he just used that language. If we can do it politically, fine, but if necessary, we’ll do it by force.

So, it was an “acceptance”, in quotes, with their fingers crossed behind their backs, that they wouldn’t live with a smaller Israel. I can’t go into detail here, but what was interesting to me was Ben-Gurion’s argument, among other things, was that while a small state was indefensible, and that if you’re going to have a Jewish state—he just picked this number—we can live with 20% of Arabs in a Jewish state, but we need 80% control. Therefore, we have to conquer the rest of this territory so that we can increase the percentage of Jews. But what I show, I think successfully in the book, is that if the Jews had genuinely accepted the 1948 partition and compromise, the birth rates and immigration would have led there to be an 80% majority within about four or five years. So, they didn’t need to conquer other areas where there were Jewish settlements to reach that that figure. I haven’t seen anybody else make that argument. On the other hand, I haven’t seen anybody challenge my assessment.

Robinson

I want to turn to contemporary mythologies. We have recently seen this devastating and brutal Hamas attack on Israeli targets, including many civilians, and now we are seeing a massive Israeli reprisal in Gaza. Now, some people might say, and I’m sure do say, that Hamas’s recent attack is confirmation of one of the stories that you regard as “mythology,” that is to say that Hamas is bent on the destruction of Israel, won’t stop until it destroys Israel, and there is no possibility of negotiating with people who are motivated by pure hatred and a desire to end Israel and wipe it off the map. How would you respond to someone who says that the recent events actually confirm what you regard as mythology?

Slater

I’m going to answer that in two parts. In the first part, I go into great detail in my book of a number of efforts by Hamas to initiate negotiations with Israel. Basically, by the 1980s or so, both Hamas and Arafat with the PLO had accepted that they could not destroy Israel, that the best they could do would be to get a Palestinian state on territory, particularly in the West Bank and in Gaza. There were many efforts by Hamas leaders to enter into negotiations to have a 20-year truce, so on and so forth, and Israel refused to talk to them. I have a few good quotes which I think will put this to rest. I write—this is on page 288—that: “Although there was some ambivalence about Hamas, they say one thing that seemed to be peaceful one day, and then they would say something militant another day.” So, there are inconsistencies and so on. But this is how I conclude: “Yet the overall evolution of Hamas’s policies was unmistakable.” And I go into what was said by leading Israelis at the time about the changes in Hamas.

Among other things, they officially eliminated their charter which is highly antisemitic, and replaced it with one which was anti-Zionist, and in various ways was much more moderate and still quite religious and so on. So, the charter and the policies changed. In late 2006, Yossi Alpher, a former deputy head of the Mossad, wrote: Hamas’s conditions are almost too good to be true. Refugees and the Right of Return to Jerusalem can wait for some other process, Hamas will suffice with the 1967 borders, more or less, and in return will guarantee peace and quiet for 10, 25, or 30 years of good neighborly relations. Similarly, in 2009, Efraim Halevy, the former head of the Mossad, and then the national security adviser to Ariel Sharon of all people, wrote that “Hamas militants have recognized their ideological goal is not attainable and will not be in the foreseeable future. Instead, they are ready and willing to see the establishment of a Palestinian state in the temporary borders of 1967.” However, he concluded dryly that “Israel, for reasons of its own, did not want to turn the ceasefire into the start of a diplomatic process with Hamas.” Last thing: Ami Ayalon, former head of the Shin Bet, concurred that Hamas’s policy was significantly changing. He said, “The resolution of an existential conflict, like the conflict between us and the Palestine, occurs when the dream is separated from the diplomatic plan.”

So, you have a long history that, moreover, in the last 10 years until this recent attack, Israel has concurred—and not only concurred but helped—with continued Hamas rule over Gaza. The Israelis want to separate Gaza from the West Bank, making a two-state settlement even more impossible than it already is. An agreement had been reached—I’m sure it’s more than a tacit agreement, there had to have been conversations off the record—that Hamas will end attacks on Israel, and moreover, will control and prevent attacks on Israel from more radical groups within Gaza, like Islamic Jihad, in return for Israel allowing it to continue to rule over Gaza. And Arab states began providing money, with Israelis permission in the last couple of years, to shore up Hamas rule.

So, until this latest horrendous attack by Hamas, there was a de facto agreement that seemed to stabilize the situation. Nobody predicted that it would lead to this kind of conflict. And partly the reason no one predicted it is the Hamas leaders seemed to be reasonably moderate, and all of a sudden, you have these suicidal maniacs who attacked Israel. I don’t understand how that could have happened. I suppose what happened is that the fanatics within Hamas gained control over Hamas. You can make a general assessment that conditions are such that sooner or later, there’s going to be an attack, but nobody predicted this kind of attack. And nobody predicted because it was basically unpredictable. It’s inconsistent with what Hamas has been for the last 20 or 30 years.

Robinson

You’re suggesting that the moderating tendencies, or the appearance of moderating tendencies, within Hamas that was noted in the quotes that you have between 2006 and 2010 was quite real. But because that opportunity was not taken to deal with these people, they may have empowered the fanatics who said, essentially, we have nothing to lose here. We’re never going to get a Palestinian state, settlements are going to continue to expand in the West Bank, Gaza looks like it will remain under de facto Israeli control indefinitely. As we looked out into the future before these attacks, it seems like, as you pointed out in the book, Israel’s policy was essentially to maintain the status quo, and the status quo was going to be deeply unjust to Palestinians.

Slater

Yes, but the more important point is Hamas, by its agreements to end terrorist attacks in Israel and prevent others from engaging in terrorist attacks, they accepted, in practice, if not rhetorically, if you let us rule over Gaza, we won’t attack Israel. They also want to rule over the West Bank. There certainly could have been a conflict between the Palestinians in the West Bank, or the Palestinian leadership in the West Bank, and Hamas, eventually. So it wasn’t only Israel, it was also Hamas, which accepted that there was not going to be a Palestinian state. And of course, the judgment Hamas leaders were making—not the terrorists now, but the leaders were making—was that if we attack Israel, we’re going to be bombarded and repressed, and there will be huge casualties. And that happened—it’s happened three or four times; this is not the first time that Israel has bombed Gaza. And if they go in, it won’t be the first time they sent troops in there. After three or four of these things, Hamas apparently, seemingly, came to the conclusion that there was no point, that there was everything to lose and nothing to gain by continuing quixotic attacks on Israel.

All of that now has been blown up by these attacks by these Hamas fanatics. How this is to be explained in light of what Hamas has apparently been willing to accept, we don’t know. And possibly, that simply there’s a group of fanatics who were not under the control of the Hamas leaders would be very hard for me to believe and very hard to understand. If the Hamas political leadership said, yes, let’s support this attack—that if there was this kind of attack, the worst terrorist attack on Israel with these murderous fanatics slaughtering innocent people—they knew they had to know with 100% certainty that there’s going to be a massive Israeli response. So, why did it occur? We don’t know the answer to that.

Robinson

It does look suicidal. It’s bizarre, it in a certain way.

Slater

It’s literally suicidal because the 1,500 Hamas fighters that went into Israel had to know they were not going to get out of Israel, that they’re going to be hunted down and killed. So, they were suicidal. It’s fanatical, suicidal terrorism at its worst. And they also had to know that the killing of the terrorists was going to be only the first step for a massive Israeli response, which we are already seeing in Gaza. Israel is not only bombing, but they’ve cut off electricity, water, and food, and they control the entry of all of those things. What did Hamas think? What did these people, if they had any leaders, think was going to be the case? What Israel is doing in Gaza is unprecedented only in its extent. There were other massive attacks on Gaza, and in some cases, the West Bank, after a particularly egregious terrorist attack on Israel. But these other attacks on Israel, which have led to massive Israeli responses, would be maybe the bombing of a restaurant and 25 people are killed. That’s bad enough, but it doesn’t compare with what the fanatics did this time.

Robinson

Would you say that this is the bleakest moment for the Israel-Palestine conflict, maybe since the start? Certainly, it’s a moment where it seems like the prospect of a Palestinian state has entirely collapsed, and had collapsed already before this recent attack—as you point out in the book, Israeli public opinion had turned against it. There really seemed like there was no chance in the near future for a just settlement to the crisis. Are we in the most dire moment that we’ve been in?

Slater

Yes, I think so. And I also think that prospects for any kind of political settlement are zero. They weren’t much more than zero before this, but they certainly are zero now. I absolutely cannot see how anything good can come out of this. Now, I agree with the Israelis that they now have to destroy Hamas, but it’s an impossible moral dilemma. The only way of destroying Hamas is to go into Gaza, and that has already led to thousands of casualties. And each day that goes by with more bombing—with no or very little food, water, and electricity, and so on—there’s going to be enormous civilian casualties.

So, it’s an impossible situation. I can’t see anything but more tragedy coming out of this. I hate to say that, but that’s my view. And even before this attack, I thought the chances of a political settlement were hopeless, not because of Hamas, but because Israel simply was not going to remove its settlers from the West Bank, and do just the opposite: it was going to expand it. So, Israeli control is going to continue. Who knows what they’ll do in Gaza, whether they will try to occupy it, or more or less level it and then leave. I don’t know, but whatever they do will be bad. Even though it is necessary to destroy Hamas, that’s the dilemma. It’s just simply horrible.

Robinson

You discuss extensively in the book the role of the United States, and you do argue that the US’s failure to put sufficient pressure on Israel to abandon some of these refusals to make reasonable concessions has been part of why the opportunities were missed to resolve the conflict. In this present moment, what do you think the United States government ought to be doing to minimize the tragedy unfolding?

Slater

What it ought to do is to stop placing the entire responsibility on the Palestinians and even on Hamas. I don’t think it can do this, but I think in principle, they should be taking whatever steps they can to stop Israel from continuing to attack the civilian population in Palestine. The Biden administration is not happy that Israel is doing this, but they don’t feel that they can, or successfully be able, to exert pressure.

Right now, it’s hard to know what the United States can do. I don’t like Biden’s rhetoric, which places the entire responsibility for the overall conflict on [Palestine]—he shouldn’t be saying that. He should be saying something along the lines of, this is a tragedy in which both sides have played a role, it’s time to end that, and so on. And further, I make this argument in the book, even if you have a change of rhetorical policy on the part of the United States—or even going beyond that, if the United States threatened to cut off military assistance to Israel unless it did A, B, and C—there’d be a very good chance that the Israelis would say, go to hell, we’re not going to do it. They’ve got enough arms of their own.

But the rhetoric is bad. Blinken, Sullivan, and Biden, of course, should, at least rhetorically, recognize the complexity of the situation. They can say Hamas has to go, and I agree with that, but Israel has to be prepared to reach a political settlement with the Palestinians—something along those lines. But they’re not going to say that, both because they probably don’t understand the extent to which Israel has been the obstacle to this, and also for the obvious political reasons.

Robinson

And it would also be helpful if Israel were told that compliance with international law is not optional.

Slater

Yes, absolutely. Those are the kinds of things which should be being said, and are not, and almost certainly will not. I think that there will be pressure from the United States. I’m not sure whether the pressure would be anything more than behind the scenes rhetoric—I read today the Israelis are telling the residents of Gaza to get up and move to the south—that as this continues to go on, the American government will probably be hoping that Israel’s will stop. I think you’ll see rhetoric or stories that, behind the scenes, the United States is trying to exercise that pressure and influence to prevent that. But Israel in the past has ignored those kinds of pressures, or the kind of hopeful rhetoric, and so on. It’s hard to see how this is going to end.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.