How Feminism Shaped the Carceral State

Law professor Aya Gruber argues that feminists should rethink carceral notions of gender justice.

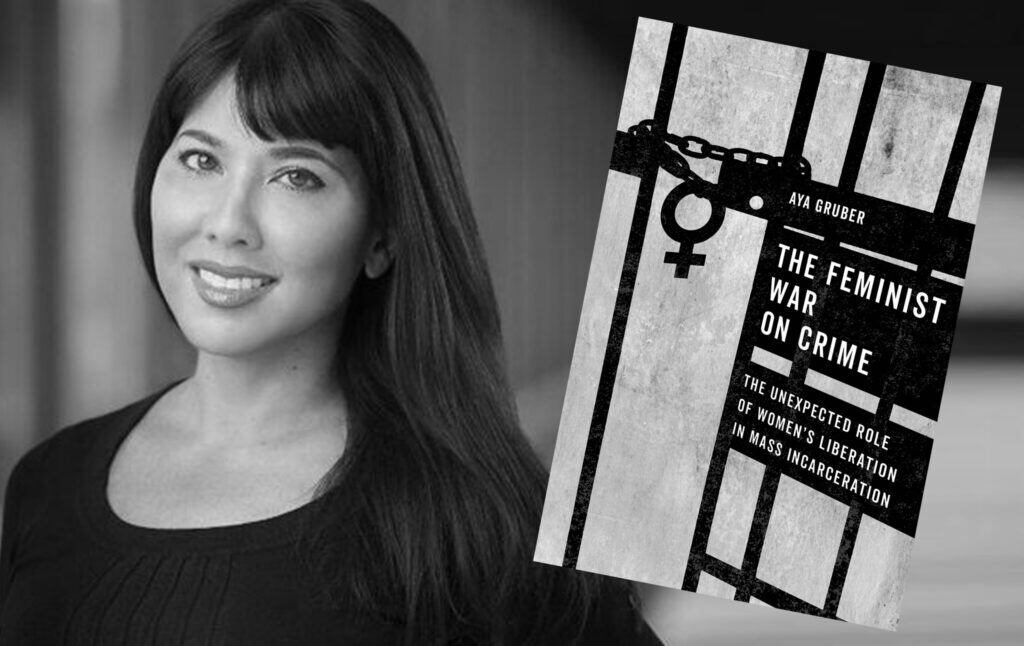

Professor Aya Gruber, of the University of Colorado Law School, is the author of the book The Feminist War on Crime: The Unexpected Role of Women’s Liberation in Mass Incarceration, available from the University of California Press. She recently discussed her book on the Current Affairs podcast with editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson. This interview has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

Okay, so this book is bold and provocative. You challenge a number of mainstream beliefs held among many contemporary feminists. I think that a lot of what you say here is quite controversial. I would like to hear your defense of some of the positions in this book. Let’s begin here. One of the things that your book does is to challenge what is often known as “carceral feminism”—that is, the strain of feminist thought, of pro-women’s-rights thought, that ends up veering towards criminalization and the use of criminal law as a tool for advancing women’s rights or combating patriarchy.

I think one of the places to begin to understand the nuance that drives many feminists like yourself to the critique of this “carceral feminist” set of ideas is at the public defender’s office. You’ve worked as a public defender. I’ve worked in a public defender’s office before. Certainly what one sees firsthand are the various ways in which a system set up to prosecute sex crimes, to prosecute domestic violence, and to prosecute rape doesn’t necessarily end up serving the interests of anyone. And so perhaps we could start with what you observed and what people need to understand about the real world of sex crime prosecution that can begin to open them up to the fact that there are a lot of difficulties and complexities in what may seem initially like something quite simple: the idea that, well, sex crimes aren’t prosecuted sufficiently, so we need to prosecute them more and more punitively.

Gruber

I’m going to begin with the end of your question. And then I’ll move back to the more generative question of how I formed my thoughts on feminism and incarceration. But just to start with the end: it’s very interesting to look at the media coverage of sexual assault, or the mainstream liberal discourse on sexual assault. It’s always the idea that it’s not prosecuted enough. The idea that what we need more of is people being prosecuted for sex crimes as if that’s an end in itself, as if prosecution is the gold ring and the ultimate goal. But what we need is less violence; we need these gender-based crimes not to happen in the first place. And that may or may not happen because of prosecution. So even the framing of the discussion just shows how deeply the prosecutorial instinct has influenced the way we think about violence against women and gender equality. So I just wanted to point that out.

But where this started for me is that I’ve been a feminist as long as I can remember from junior high school onward. And at the same time, I’ve been skeptical of incarceration. I grew up with stories of my mother being in a Japanese internment camp. So I had two sides. One side is very much like, we need to use all means available to achieve gender equality. And the other side was, well, prisons are not so great. So I always thought of it as this dilemma, and I was mired in this dilemma in law school. Do I pick my feminist side, or do I pick my anti-carceral side?

I felt this dilemma so strongly that when I was about to become a public defender, I actually did worry more about representing a man charged with misdemeanor domestic violence than representing someone charged with murder. I had this concern about crimes against women. But then I started practicing, and I just started wondering why I thought this was a dilemma, instead of a misplaced emphasis on incarceration. I did work in a specialized domestic violence court, and it was designed and built by feminists. But what I saw was more of the same. It was a revolving door of poverty, collateral consequences, and jail, mostly for poor people of color. There were a lot of women who called the police because they needed immediate help. They wanted violence interruption, but they didn’t necessarily want this huge penal machine that could even make them ineligible for public housing. Immigrant women didn’t necessarily want their spouses deported. So what I saw, at least in the domestic violence realm, was this system that did help some women. But it came at these enormous costs, and it actually harmed many women. So there’s always this emphasis on more prosecution as if that’s the solution. But in rape cases, it’s a little different than domestic violence, because the victim and the person accused aren’t as intertwined in their lives. They could be strangers in the case of rape. Women find that this promise of healing and deterrence in the criminal machine is always less than they had hoped. And so this book is my attempt to untether the important feminist goal of eradicating gender violence from this system that has its own embedded structures and pathology.

Robinson

I think one of the important points that people might not quite grasp is that prosecutors are ostensibly on the side of people who are the victims of crimes. But in practice, oftentimes people who file a complaint and who do enter into the system hoping it will bring them justice, find that there are independent interests that prosecutors have that often trample on what the people who are making the accusation actually want, or actually would see as justice. Someone who is going in expecting or wanting a restorative justice process won’t get that. There are even cases, of course, where the person who was harmed ends up being compelled to testify or ends up not wanting to testify, and then the case goes forward without them against their wishes. The wishes or demands or needs of the victim are not prioritized by the criminal punishment system.

Gruber

That’s totally correct. Consider the victims’ rights movement. I discuss it quite exhaustively in the book: how they were politically positioned, how they really did start out protecting victims against prosecutors, and then how they came to position victims as a tool of prosecution in the state. But I’ve always been really intrigued by the fact that the victims’ rights movement touted the criminal process as one big process of healing. Those of us who’ve worked in the system know it’s anything but healing. If the victim wants the perpetrator put in jail, that’s what you get. But in order for the state to be able to deprive someone of liberty and cage them, there needs to be a process, right? There needs to be proof. In a rape case, the main proof is the testimony of the woman. So anybody who’s ever been subjected to cross-examination knows this is exhausting, depressing, hard stuff. You have a person, a trained lawyer, basically trying to show a group of people that you are a liar, that you don’t remember, that you aren’t credible. To me, that is the antithesis of what somebody needs to heal. But that’s also the best system we have, the only system we have to protect defendants against just willy-nilly being jailed by the government. So the thought that this process could be a win-win situation for victims was always fraught, but that’s how it’s been sold. If something happens to you, here’s what you need: you need this really exhausting, long-drawn-out process where you are interfacing a lot with men, right? Male police officers who may or may not believe you, who may be patronizing to you, or they may or may not treat you in the same way. There are overworked prosecutors. Maybe you’ll have a victim advocate on your side. But this is going to be exhausting. People are going to put you under a microscope. And at the end of it, what you might get is somebody else having their liberty deprived. And that’s what we’re promising you as healing. That always seemed a little bit odd to me.

Robinson

I think a lot of people probably find that it doesn’t bring them much satisfaction to watch. It’s not just that you have your liberty deprived, which is almost the softest way we could put it. The reality of the American prison system is that you are watching someone be thrust into a place where they themselves could be subjected to horrific sexual violence. You talk about sex offender registries in the book. When criminal punishment in the United States is brutal, it’s really truly brutal. So you’re telling someone that they have to accept that brutality is going to be inflicted on the person—which may be in some cases what they feel like would be justice—but in a lot of cases probably isn’t going to feel like justice when it’s carried out.

Gruber

Right. Don’t get me wrong. There will always be people who are subject to criminal behavior by other individuals, whether it be a sexual assault, or a burglary or a theft. Some people get really upset that something was stolen from them, and they really want to see that person in jail. And that probably has to do with their priors about what they think are just deserts or about how many people should be in jail and who is a good and bad person. But I worry about women who are subjected to gender violence. A lot of them may be very progressive on criminal justice issues, especially if they’re feminists. They may not have those vindictive, “let them rot in hell” priors. Yet they may still have bought into this idea that because rape and domestic violence have traditionally been under-punished, that punishment, in and of itself, constitutes gender justice. So it’s like the “gold standard” of feminism. And that’s what I’m trying to interrupt a little bit. If you’re a person who buys into the idea that our criminal system—which is a mass incarceration system that is harsh and that is an outlier in the world, if you’ve ever looked at the conditions, they are just torturous conditions, concentrated sites of sexual violence, and places of extreme racial prejudice—if you still think that there’s justice within that system, fine, you could be a victim of any kind of crime, and you will feel good about somebody going to jail. I just have a sneaking suspicion that many contemporary women are very aware of the problem of sexual violence, or see a future where we can change sexual norms regarding consent, and regarding relationships, and really do want gender justice, but just don’t have any way to see it, outside of this system. I think when they go out and protest in the George Floyd protests they otherwise see something that needs to be reformed or even torn down and built up again from the ground.

Robinson

Just to go back to what you were saying about how it involves being cross-examined in a proceeding that is painful and often embarrassing—it’s excruciating. When I was briefly an intern in a public defender’s office, there was something that really discomforted me about having to work on cases where it was a necessary part of our job to try and discredit someone who had gone through a horrible trauma. It did seem a moral conflict. It seems immoral to have as part of your job description the task of trying to prove someone a liar, even if you know that they’re not. Your job is often to raise a reasonable doubt about what they’re saying, and seize upon things that are weaknesses in their testimony. But that is structurally built into dealing with this kind of social harm through an institution that sets up an antagonistic procedure between two parties, prosecution and defense. And the issue is, will this person lose their liberty or not? And I appreciate that you draw attention to the fact that it puts people in this position of having to do things that nobody really thinks constitutes justice, or that nobody really wants to do. No public defender wants to have to discredit someone who’s been through a horrible trauma.

Gruber

Absolutely. I have myself been cross-examined quite a few times. It’s not pleasant to have a very smart person looking at everything you say, and trying to catch you in a contradiction, and then bringing up your past and saying that you don’t know or you don’t remember, that you did this, or you did that. These are well-founded critiques of the adversarial process, well-founded critiques of the effect that cross-examination can have on witnesses who are cross-examined. And the fact of the matter is, most people who get up on the stand and swear to tell the truth, are telling the truth. Now, there are always people who don’t remember or who are fudging some things, but to get witnesses who come up and just lie under oath is rare. But it happens, and it’s the job of the defense attorney to figure that out. So this is all a really good critique of cross-examination. But it’s one that happens to be directed mostly against defenders, and curiously directed by progressive feminists against defenders, when it’s equally true of prosecutors, prosecutors who aren’t protecting people from the power of the state. So many times, we had defense witnesses, and the prosecutor hammered on how this person—say, a random witness—is a sex worker, and how she’s on crack, and how she was playing her trade, right? And how she couldn’t possibly know anything, because she has this long record of prostitution offenses. And can you imagine being that woman on the stand having her life brought to bear just because she happened to be in a place to witness something? And every day, prosecutors cross-examine the most marginalized among us, emphasizing how horrible they are as people, how horrible their records are, and how they can’t be trusted because they’ve taken drugs. We do this in order to put them in jail or put other people in jail. And yet, it’s the defenders who are trying to keep people, including women, out of a system that can be deadly. Look at how many people who haven’t even been convicted of anything yet are dying by the droves in places like Rikers Island. Even if you survive the jail conflicts, you have civic death. If you’ve ever known somebody on a sex offender registry, it’s almost impossible to have what we would consider a semblance of a civic life. It’s always the defenders that are seen as the evil cross-examiners by other progressives, which is a little curious to me.

Robinson

We know for a fact that the justice system tends to be more unjust toward poor people and people of color. You worked at D.C. Public Defender’s, right? They are excellent. But around the country, oftentimes people don’t in fact receive quality representation if they are poor. So when police and prisons and courts resolve social harms in poor communities, this is a blunt mechanism that we know from all of the progressive critiques of the criminal punishment system often hurts more than it helps. Often it is incredibly likely to ensnare innocent people and to disproportionately and unfairly punish typically Black men.

Gruber

We have to figure out what it is that we as feminists—and I consider myself a feminist—want to do here. I think what feminists want to do in the criminal law space is reduce gender violence, sexual violence, and just violence in general. And so when you look at the whole institution of policing, prosecution, and punishment, it is an institution of violence. Police go out on the street, and they mostly aren’t sleuths who are solving cold cases. They’re mostly people who are intercepting poor people, mostly poor men of color who are going about their daily business. Sometimes they’re engaged in criminal activity, and sometimes they’re not, and these encounters are extremely violent. And what this leads to is entry into a system that—especially when it comes to misdemeanors—is this revolving door system that is meant to process volumes of arrests, and lead to either probationary or jail sentences. And then the person goes to jail, where they’re subjected to incredible amounts of violence, including sexual violence. And this is what that system does. Now, there could be things adjacent to that system, where we have outreach, where we have victim services, where we have healing, where we have restitution, but all those can be done without the violence of the system. So I would think if we’re feminists and we want to reduce violence, we would be sharp critics of the system, which most feminists are. They really do go to protests such as Black Lives Matter protests. They do say that mass incarceration is a real problem. They say prison conditions are horrible. But yet, there’s this idea that feminism can do these insurgencies within this built up system—that was built upon violence, and built upon racism and classism—and that we can nonetheless go into this system and produce a good and feminist outcome. This is where my book comes in. I’m saying, well, look, there’s this system. And there’s this whole history of why feminists have by happenstance or design or co-optation become part of this system. Here’s a feminist agenda that doesn’t buy into the logic that this is the best we’ve got, that reform is the only thing we’ve got as feminists.

Robinson

Let me present to you what someone who is not a prison abolitionist would say to you, which is: We can critique the prison system. I believe in prison reform. I believe in trying to make it more humane. I believe in strong standards of evidence. But the fact is that in the contemporary United States, certain kinds of violent crimes are gotten away with by very powerful people. If you look at the career of someone like Harvey Weinstein, if you look at someone like Bill Cosby, powerful men who commit sex crimes do so with impunity and nothing happens to them. They commit violent acts regularly, and they know that they’re going to get away with it and not be punished. We want a more egalitarian system, but we need to make sure that those people who commit violent acts receive some kind of punishment. And the big problem right now is that they tend to get away with it.

Gruber

There’s a lot to unpack in that statement. If you look at powerful men like Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby, yes, they are elderly men who will probably die in jail. So there is that sense of punishment and accountability for them. Now, why are we concerned about these powerful men? Because of the idea that for every Bill Cosby, there’s a Donald Trump just getting away with sexual and all other kinds of offenses because they are immune from the operation of law. And this is a problem, right? And so when you look back at Harvey Weinstein, there were a couple reasons why he engaged in this behavior and why it went on for so long. First of all, he didn’t think what he did was a crime. He was positioned in a market with a massive imbalance of power in the hands of corporate executives who make movies and are highly paid; and the actors have precarious employment. If you get the part, you win the jackpot. And they are taking advantage of these actors on every level within this unequal market, to the point where they’re raping them. And the victims think, this is just part of the game. Now, once other people started to say, well, actually, no, Harvey, this isn’t just life, this is a crime, then rich and powerful people have the money and the resources to investigate people to protect themselves. The problem with these powerful men isn’t a failure of our criminal system not being tough enough. The system is plenty tough. It’s plenty tough on the regular suspects. Even if it was built for powerful white men, which it wasn’t, it was never built to punish powerful white men. But even if it was, it is a state run, under-resourced system that doesn’t have the power to go after people who are beloved or politically connected. So I get it, the idea that powerful people are immune from the rule of law is disgusting. It is a real reflection of how we allow certain people and certain men to accrue power in this country. But it’s not going to be remedied through just making everything a life offense and dialing down the proof in cases, because that criminal system will not distribute to those people. It will distribute to the least well-off. So the evidentiary rules that allow a defendant’s prior bad acts to come in—not even in just sex crime cases, but in any cases—they basically revised the rule on prior bad acts in order to have the parade of witnesses in uncharged crimes testify against Cosby. Well, that rule now applies to your next shoplifting case, where I can bring in 20 shopliftings for that person. So we’re making rules to get at people who are immune from the rules. And the effect of that will be to just make it even easier, make sentences even longer, broaden crimes even more for the policed segment of society.

Robinson

I interpret part of what you’re saying as: if these crimes occur because people have disproportionate amounts of power and wealth, and if people are victimized in part because they don’t have power and wealth, one of the things we need to be doing is thinking about, well, what are the changes in the structure of power and wealth that would prevent these kinds of things from happening in the first place? So a workplace in which there is one guy at the top and everyone around him is a sycophant, and he can do whatever he likes, versus perhaps a unionized workplace, right, where complaints are taken seriously, and someone at the top knows that they couldn’t get away with something because there are accountability mechanisms within the institution that they’re in. The crime doesn’t arise in the first place. Or situations where people have to stay in abusive situations because they’re poor, the abuse can be prevented if you are able to go somewhere else, because you’re not desperate, you’re not poor. So thinking about the things that enable abuse to occur with impunity is just as important as looking after the fact at, well, given that we think they do occur because of these huge imbalances of wealth and power, how can we use this blunt instrument of the criminal legal system to create something that is never going to be justice, but is like the best thing that we could possibly think of?

Gruber

I’m all for the structural focus, the ex ante focus rather than the ex post of, well, a crime has occurred, now what can we do to pick up the pieces? Because I know in the ex ante world, what we’ve been sold and given and told so many times is that we’ve got the criminal system. So I really do like the focus that you’re suggesting on the ex ante. One of the things I say in my book is that we should look more to these antecedents of sexual and gendered harm. My book is actually not a prison abolitionist book. I argue that we should really think about putting some effort toward prison reform and abolition instead of constantly strengthening little pockets of it because we think that’s going to get at gendered crime. But mainly, my book is about the division of feminist capital into intellectual, political, academic, economic, and social capital spheres. A lot of energy has gone into justifying and expanding the criminal legal system and the American penal state, and I just think some of that energy can go elsewhere. So I don’t think it’s a Herculean task to go in there and say, Okay, who are the women most vulnerable to gender-based violence? And why are they vulnerable? So precarious workers are completely vulnerable to sexual harassment and even empowered corporate women are vulnerable to sexual harassment, because they rely on their job. So when you have a harassing boss, you’re not empowered to tell him to stop and then report it. So then we have to have all these rules about keeping identities secret, and how this is going to go into making sure it doesn’t affect your next job. If we didn’t have such an imbalance of power, or precarity, if we had strong unions, if we had the ability of workers to be on lockstep salary and advance in salary in some fair and meaningful way, instead of cronyism, a lot of this would stop. But if we really want to get a bang for our buck in combating sexual violence, we’d probably look to sex workers, and especially trans sex workers of color. They are the people who experience sexual violence at enormously high rates. They’re never the poster children for victimhood. That’s always more of a middle-class—often white—woman, maybe somebody in college, and then it has to do with matters of consent and not the forcible violence that is exacted on these marginalized people on a daily basis, sometimes multiple times a day. We need to look to that community and ask these women who are really placed in vulnerability, what do you need and what can we do for you? What will improve your circumstances? I think that would get us really a long way in making a dent in gender-based violence. But I think the whole narrative has grown up around ideal victims who tend not to be marginalized people or victims who happen to have engaged in criminal activity. And criminalized activity is often necessary for marginalized people to survive. So I even questioned the construction of who is and isn’t a criminal in that respect. But we tend to look at white middle-class women who went on a date with a powerful person who violently raped them, and then the police didn’t take them seriously. That is all very important to look at. But the framing is carceral from the beginning. It’s not like, how could we have prevented this from happening? The idea is well, this happened totally randomly, who would know that you would go out on a date and get raped by this powerful guy? And then the whole thing becomes carceral. How could the police have done better? How could the prosecution have done better, and how could he have gotten a sentence? But if you look at the most vulnerable women, the sites of vulnerability, you have a different narrative altogether, which can lead you to concentrate on these ex ante preventions. But we’re mired in these one-off stories of unpreventable and horrific crime for which the criminal legal system is the only option. And I think we really just need to shift that frame as feminists and look on more promising and less costly areas of reform.

Robinson

Now, you say that your book is not necessarily a prison abolitionist book. You do say that you are asking feminists to adopt an unconditional stance against criminalization no matter the issue. That seems a very strong statement. And I wonder if you could explain what you mean by an “unconditional stance against criminalization.” Are you saying that when a violent sex crime occurs, there should be no prosecution, there should be no police involvement? What do you mean by that?

Gruber

Feminists have been engaged in a century-long (or longer) project of at once trying to gain equality and reduce violence against women, and looking at issues that arise because of gender that keep women subordinated. But at the same time, they’ve also engaged in a very robust project of expanding and strengthening the criminal apparatus in this country. So feminism has contributed to vice and anti-prostitution crusades and expanding surveillance, policing, and incarceration in the U.S. up until this day. When you look at the consensus, it’s that we shouldn’t have more mandatory minimum sentences, right? Even the Koch brothers—even the right–agrees that mandatory minimum sentences aren’t a good idea. In the last five years, when states have created new mandatory minimums, it’s around violence against women. This involves mandatory minimums for rape crimes, mandatory minimums for domestic violence. Where we’ve seen expanded criminal law definitions, it’s around violence against women; and where you see the concessions were in the First Step Act for bringing back a more robust parole system that was completely eviscerated in the 80’s, it was making parole harder for crimes of domestic violence. What we’ve seen is this investment in criminalization. The reform is around criminalization. What I’m saying to feminists is, where there’s a real problem where this certain segment of men is gleefully getting away with and bragging about, say, non consensual condom removal. Or problems with sex workers who are being subjected to intimate partner and exploiter violence. When you look at those, don’t jump to, we should send more police in there, we should make this a new crime, we should have prosecutors. So, no criminalization. Let’s look at everything we can do. There are many ways to approach these issues. Let’s slice the pizza every way we can before we go to criminalization. In the preceding chapters, I show that criminalization is just so fraught, it’s so costly, and it has backfired so many times that we can learn the lessons of the past and try other things before we as feminists adopt the carceral stance. That’s not to say that other people aren’t right. There are going to be victims groups, tough on crime groups, or others like politicians who, when it comes to sex offenders, they are going to say, okay, this is the worst thing ever, and they can adopt the carceral stance. I don’t think feminists should. Now, should we tear down all prisons tomorrow and just hold hands and sing Kumbaya? I mean, that’s for another book. As feminists, we’re not nearly there yet. I mean, most mainstream feminists really do have this impulse to say that gender justice will be putting somebody in jail for x crime. And that’s the impulse I’m trying to interrupt.

Robinson

I should mention to our listeners that your book is, in fact, largely historical. You track the development of feminism over time and the way that feminist ideas have been used to build the carceral state. I’ve been asking you a lot about the contemporary situation and about the theory of punishment, and if people want the history, they should really dive into your book. I wanted to finish up by asking you about one of the cases that I think really illustrates some of the tensions at work that you are trying to bring out here, which is the notorious Brock Turner case from a couple of years ago. As a Stanford University student, he was convicted of, well I can’t remember the exact charge. But the judge was perceived to have given him too lenient a sentence of something like six months in county jail. There were very serious consequences for the judge, who was removed from office. There was a massive petition to recall the judge who was perceived as going excessively easy on him. And, in fact, I think the judge lost a job later on. Anyway, it was an interesting case because you had a clash between the #MeToo movement and public defenders, or a lot of public defenders who were opposing the recall of this judge and saying, actually, it’s very important that judges not be punished for leniency. There was a change in the California law to increase punishment after this. So yeah, this case really does illustrate some of these difficulties. I take it that you believe that it was wrong to go after the judge in that case, and that some of the consequences of that case illustrate the direction in feminism that you are worried about?

Gruber

Yeah. I think this was a very particular branch of feminism. And don’t get me wrong when I say we’re a long way from abolition. I should mention that we’re getting closer to a time where feminists are really looking outside of the carceral space, and also looking within our mass incarceration system to see the ways in which it itself inflicts violence upon women. So I’m thinking about INCITE, which has been around forever. Black and Pink. Survived and Punished. Many of the prison abolitionist feminist groups, often held by women of color who are thinking differently. This is not to say that there is just one feminism. There are feminisms. But in mainstream feminism, we had this idea that in the Brock Turner case, because he was privileged, he was going to be immune from the law. In the minds of many people who’ve never set foot in a jail—who’ve never known somebody who’s had lifetime sex offender registration and 15 years of probation—you might imagine that that’s quite a slap on the wrist as a lot of feminists see it. If you’ve never been around the horrors of the criminal legal system, and you’re just looking from afar, you think, Oh, just six months out of your life, that’s nothing. You know, it’s not nothing. And I think it does kind of a disservice to anti-carceral efforts more generally, the way that Brock Turner’s sentence was framed at the outset. But that being said, I think we expect that a lot of mainstream feminists would see six months as an overly light sentence, and, therefore, to be a failure of gender justice, because once again, they’re seeing gender justice in the situation as jail sentencing and people going to jail. So you know, seeing that this quote unquote powerful kid who was white and went to Stanford and somehow got a light sentence was very similar to Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby, although I think there are very large factual differences in the cases. And so they asked for, again, this internal structural criminal legal change that they hoped would get at the powerful guys. And one of these changes was to let judges know that if they’re too lenient in sexual assault cases, we will get you fired, we will get you recalled. Or to have three-year mandatory minimums, where if judges want to be lenient, they can’t. So we’re going to get the Brock Turners of the world with this. That was a very common way of thinking. But it flies in the face of why these crimes are occurring. And that is just the carceral solution. And people were very worried at the messages being sent by this recall, because we’ve seen it so many times before. If a judge releases a misdemeanant and that person happens to commit a terrible crime, the judge goes in the newspaper, and they’re never going to release a misdemeanant again. The focus is on leniency, and so judges fear leniency. So this was self-proclaimed feminists doubling down on making judges deathly afraid of leniency. Now, the way the woman who spearheaded the campaign explained it is, well, we’re not going after Judge Aaron Persky because of his leniency, we’re going after him because he’s a white male racist, who happened to like Turner, a white male, and he wouldn’t have treated Black men this way. It was an odd kind of argument, the idea that he ought to treat white men and Black men really harshly. But when you look at his record, he went with the six-month sentence because the female probation officer recommended it. And most people don’t know about the pre-sentence report system. But most judges, because there are so many sentencing factors—there’s legislation guiding it, and they don’t have time to do the factual inquiries—they leave it to the probation department to prepare a detailed pre-sentence report adding up all the factors and doing a calculation to come up with the sentence. Because Brock Turner was a first-time offender, the sentence was on the low end of the range of their sentencing regime. And so he followed probation, which was his trend to follow probation. So all these ideas—that they took him down for something other than being lenient or giving a rape defendant due process, things that garnered the country’s imagination—were simply not true. There’s recently been a Twitter controversy where the person who organized the recall has for other reasons called public defenders arrogant and stupid. It was kind of an “emperor has no clothes” moment, because I think this reveals the prosecutorial ideas of many feminists that people charged with sex crimes against women should not get the same benefits of the doubt of the system as other people charged with crimes, even though their consequences are so much more severe. After their carceral terms, they go into the civic death situation. And just an interesting footnote: that job that Persky couldn’t get was as a coach of a kids—I think a girls’—tennis team. And the reason why is the stench of sexual offense extended to him. He became an enabler of sexual offense—and therefore possibly a sexual deviant himself—by his connection to this case. So this is how broad the ripples can go. And I just don’t see them as very progressive.

Robinson

I was reading some of the interviews with the woman, Chanel Miller, who was assaulted by Brock Turner. She came out publicly with a book and her victim impact statement went viral. And there are a couple of interesting things. One interesting thing was that some of what she said kind of confirmed what we’ve been talking about. It talked about the trial as a highly imperfect or even unfair institution through which to deal with these kinds of harms. She said that having to testify felt like getting assaulted again, that having pictures of her genitals displayed to the jury was disturbing, and we can see how that would indeed be the case. So the whole trial process did not feel like justice. I’m wondering if you could respond to something she says. I think it is very difficult to respond when someone says this. She said, When Brock Turner’s sentence was handed down, I was in shock. I put aside a year and a half of my life through the proceedings, so that he could go to county jail for three months. She said that there are young men, particularly young men of color, serving longer sentences for nonviolent crimes—she was concerned about the carceral state—for having a bit tiny bit of marijuana in their pockets, and he’s just been convicted of three felonies, and he’s going to serve one month for each felony. How can you explain that to me? And then she talks about how afterwards, there was the recall and the increase in mandatory minimums, and she said that the increase in mandatory minimums felt like knowing that this sentencing would not be repeated, so she began to believe again in justice. So how would you respond to something like that?

Gruber

I think we’ve talked about this a lot. And if that is justice for Chanel Miller after this highly publicized case of a sexual wrongdoing that was a serious sexual assault, I’m glad. I’m glad that that benefit came out of this three year mandatory minimum, which now attaches to any person who can reasonably believe that the person they’re having sexual intercourse with, or some level of fondling sexual penetration, they now go to jail for three years, whether they’re an 18-year-old Black teen who says that he didn’t think that the person he was having sexual relations with was incapacitated enough not to consent, or let’s say it’s a Black teen with a white teen. And the jury says, Well, you know what, I don’t think he was reasonable in his assessment of her level of intoxication. Well, that guy gets to go to jail for three years, too. Everybody’s gonna go to jail for three years for a range of behavior that may be more or less like what Brock Turner did, maybe more severe, maybe less severe. So that’s the consequence of that mandatory minimum change. And if that made Chanel Miller heal, that is a good thing that came out of the consequence. But there are many bad things that will come out of the consequence, not the least of which is to justify three months for marijuana carriers. Not to get too in the weeds here, but penetration is defined more broadly than what most lay people think. So certain sexual touchings of the genitals with a person that a jury decides was reasonably too drunk to consent—if that’s a three year crime, it doesn’t seem unreasonable that marijuana is a three month crime. So when we pump up all this stuff, it’s not just in that victim, who gets the publicity’s case that these things flow, right? They flow in a world of racialized mass incarceration. And they justify that world. That doesn’t mean that Chanel Miller is wrong to feel healing from that. She’s absolutely right. And that is absolutely a benefit of all these pro-carceral moves, that there is a not insignificant—maybe majority—group of victims who do get some psychic benefit out of long sentences, out of mandatory minimums. And that can’t be ignored. I think they’ve been situated through years of dialogue and instinct on the part of women and feminists to see criminal justice as a gender justice end in itself, but I’m not going to say they suffer from so-called false consciousness. They feel how they feel. On the other hand, it doesn’t have to be this way. For example, Chanel Miller could have benefited from the lawyers around her explaining to her that contrary to what she’s heard, this is not an easy process. This is one in which because there was a question of penetration, the question of genitals and how the penetration occurred becomes an issue at trial. Because it’s intoxication, the level of intoxication becomes an issue at trial. If somebody told her that it would be hell to go through this, but it is what you need to go through when you’re cross-examined, right? So this idea that a rape complainant can come in and say, I was raped, and he did it, and there’s gonna be no process of testing the evidence, that we’re just gonna get to a conviction—I really think that’s what a lot of feminists want. But what are you doing to the barrier to imprisonment? Again, we’ve agreed that what we have is this horrific system. And you have to have some sort of process between the government sending someone to jail. This is a hard process, and I think the best we can do for victims who want that process is explain it to them. Maybe at the end of that process, the person will get 15 years in jail. And if that’s what they want, that’s going to turn out good for them. But there are a lot of victims who don’t necessarily want that. Speaking as a person who has experienced sexual assault and being a professor for 20 years in this field with many, many people and students coming to me and talking about their experiences, yes, some of them say, I want to go to the police. And I say, okay, great. That is what you want, here is what you can expect, and try to be as realistic with them as possible. And some of them will say, I’m so glad you told me that. I’m ready for it. Let’s go. But many say, look, I don’t know anything other than going to the police. I feel obligated to go to the police. Because if I don’t go to the police, I’m a bad feminist, and I’m a bad woman. Right? And I don’t think that being victimized puts any obligations on you. I definitely think women in this scenario need to do what’s best for them. And the thought that we all have to go to the police, or we’re part of the problem and not the solution, is part of a constructed narrative that I think is totally unfair to women who are subjected to sexual assault and who don’t buy into this kind of a system.

Robinson

About Miller’s statement: one of the reasons that she was disappointed that Brock Turner received such a short sentence was because the trial process took over a year of her life and was so horrible for her and it didn’t feel like something that gave her justice. That was why she felt like Brock Turner deserved more time. That speaks to the very failures of the criminal punishment process—the unsatisfactory criminal punishment process was at the root of her outrage at the short sentence. It did seem kind of tragic that we don’t have anything to offer her other than this deeply flawed process. Well, Professor Gruber, thank you so much for talking to me about this book, The Feminist War on Crime: The Unexpected Role of Women’s Liberation in Mass Incarceration, available from the University of California Press. I think you make a very serious contribution to some of the really difficult questions around criminal punishment and feminism that I think are quite unresolved. I’ve really enjoyed our conversation. Thank you so much.

Robinson

Well, thank you so much for having me. I enjoyed the conversation, too.