Against Managerialism

How management education promised a better workplace—and why it delivered nothing but more creative ways of exploiting people.

It was another one of those windy, subzero Chicago winter mornings as I trudged two blocks through the slush and snow to the hourly employee entrance of the Pullman Standard plant. A supervisor in a white hard-hat, all warm and cozy in a 1972 Buick Riviera, smugly waved as he drove by me to get to his reserved parking space. I was viscerally reminded every day that managers, wielding all the power and authority, enjoyed special privileges while looking down on us lowly hourly workers as if we were stupid and lazy. This was the 1970s, a time of widespread labor unrest and worker discontent that the media dubbed the “blue-collar blues”—seen most notably in the infamous ’72 General Motors Lordstown automobile workers wildcat strike.

I was then an 18-year-old unionized industrial electrician, and what may seem to be a trivial encounter with that supervisor left an emotional mark that has haunted me for the rest of my adult career. At the time, I felt animosity towards management. With hindsight, I now understand that my resentment wasn’t just personal; it was related to my class upbringing. I grew up in a lower-middle class family on the southside of Chicago near the (now defunct) steel mills. Both my father and maternal grandfather were die-hard union railroad men, and I was the first in my family to go to college. Even though I wasn’t aware of it back then, the time clock that I punched each work day at the Pullman plant had a nefarious lineage, one in which the ugly face of raw managerial power was camouflaged with a costume of benevolence.

This history begins at one of the first company towns, built under the direction of George M. Pullman, founder of the Pullman Palace Car Company, which mass produced railroad cars. Completed in 1884, the Town of Pullman was a 4,000-acre model industrial community designed according to Pullman’s vision of total managerial control over workers. The company town included housing rental units, good sanitation, an arcade of shops, schools, an 800-pew Christian church, libraries, theaters, a hotel, a bank, recreational facilities, stables—and even an underground tunnel system from workers’ homes to the plant where the luxury railroad cars were made. Taverns and saloons were conspicuously absent, as Pullman wanted to “exclude all baneful influences” from his community. Pullman wagered that his paternalistic experiment would attract the best class of skilled workers, and he hoped to circumvent the increasingly violent conflicts seen at the time between companies and their workers.

Heralded in magazines and the press, the “Town of Pullman” was a living and shining example of managerially imposed order, efficiency, and control. That glory, however, was very short-lived. In 1893, during a severe economic depression, George Pullman laid off thousands of workers and lowered wages by 25 percent, while monthly rental payments and store prices remained the same. The next year, nearly 4,000 Pullman factory workers walked off the job in a wildcat strike, resulting in one of the most bloody labor conflicts in U.S. history. National guardsmen fired into mobs of striking workers, leaving 30 people dead.

While working-class people and those who study labor history are well aware of the violence frequently inflicted upon workers by bosses and corporations in their pursuit of profit, such history is curiously absent from introductory college textbooks on management. In these books, one will not find any mention of the Pullman strike, the labor movement, or any reference to such terms as the “working class,” “class conflict” or “class consciousness.” The consolation prize is often a perfunctory mention of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 and a portrayal of unions as an anachronism and an occasional nuisance that business majors are unlikely to encounter in their future roles as managers. And, of course, the fact that corporate management—at companies such as Amazon, Starbucks, and others—has a checkered history of spending millions of dollars for anti-union campaigns and engaging in unfair labor practices is also conveniently omitted.

But a short shrift to unions in management textbooks shouldn’t come as a surprise. There is an ideology of managerialism which is propagated through the deliberate exclusion of this labor history. Managerialism, an ideology so pervasive as to seem benign, is about the glorification of an elite group of people—managers—who are said to be uniquely qualified to have power over workers and companies. On the receiving end of management—whether one is a delivery worker forced to pee in a bottle, a white-collar worker in a cutthroat industry, or in some situation in between—most workers understand that the worker-boss or worker-management relationship is fraught with conflict. Managerialism cloaks the sources of this conflict—the workplace’s undemocratic, hierarchical, and asymmetric power structures—in humanistic and benevolent terms. For example, you may have heard of the idea that “strong corporate cultures” offer workers bottom-up voice and power. What this really amounts to is a nascent totalitarianism, a means of keeping workers in line by telling them they’re autonomous and part of a “tight-knit family” but immediately instilling feelings of shame and guilt for any transgressions from the norm. So long as you’re loyal to the corporate family and comply with its “values,” you’re supposedly “empowered.” A strong corporate culture is where “slavery is freedom” and “strength is ignorance.” It’s part of what my friend Hugh Willmott, a professor of management and organization studies, calls a “double-think world.”

Take it from me. As a management professor, I’m familiar with all these psychological tricks—and the disturbing history of how we got to a point where management gurus have refashioned the manager as a coach, counselor, and visionary leader instead of the power-hungry exploiter and emotional manipulator that he or she often is. It’s a story of poorly executed research, medical quackery, public manipulation, and overrated business schools. Understanding the history of managerialism is critical because this ideology dangerously reinforces the capitalist mandate of endless economic growth and profit, which is currently driving us toward climate collapse.

Management vs. Worker Power

For the last 35 years I have taught undergraduate and graduate-level classes in management and organizational behavior, both in a private and public university (the latter, in a College of Business). While my formal title is Professor of Management, I have always struggled to identify with the field. I suspect my unease with my profession is partly attributable to my blue-collar roots. Becoming a professor was my ticket to gain self-respect. As Richard Sennett and Jonathan Cobb explain in their book, The Hidden Injuries of Class, freedom and dignity are won by acquiring “badges of ability.” But the psychic injury of class is a wound that never really heals. Trading my blue denim overalls for a blue blazer came at the cost of chronic feelings of professional estrangement and survivor guilt. (Of course, I stopped wearing the blazer once I began to teach online.)

I didn’t, however, aspire or set out to be a professor of management at a business school. That happened rather serendipitously. While I was an undergraduate student in the humanistic psychology program at Sonoma State University (the first and only academic program of its kind), I had already started drinking the California-style human potential movement Kool-Aid. It so happened that I enrolled in a course, “The Psychology of Work,” which delved deeply into the “Quality of Working Life” (QWL) and Quality Circles movements which were very popular in the 1980s. Emerging after the rising labor militancy of the 1970s and the competitive threat of Japanese manufacturing, the QWL movement involved trade union leaders and company management collaborating in experiments to redesign fractionated assembly lines. The experiments were supposed to counter the problem of worker alienation and stultifying jobs, with the aim of improving quality and productivity. QWL experiments typically included redesigning work through job rotation and multi-skilling and the formation of “autonomous work groups” that shifted decision-making authority and quality control away from supervisors to shop-floor workers.

Hungry to learn more, I discovered there was a unique doctoral graduate program in Organizational Behavior at Case Western Reserve University that had the Who’s Who of professors in the field of organization development. While in graduate school, I was thoroughly seduced by the messianic zeal of management theorists preaching a new gospel of management redemption. I came to believe that, given the right “behavioral science” interventions, management could be redeemed and corporations could be transformed into more humane, democratic, and sustainable organizations. Converted, I became a missionary whose goal was to set management on the right course.

In addition to full-time teaching, I had a side hustle consulting to numerous Fortune 100 companies. My first consulting gig was at the General Electric Lighting division’s posh Nela Park headquarters (the historic property was sold off in 2022). Working with their organization development staff, I was charged with assisting in developing and implementing “self-managing teams” in a GE manufacturing plant. Both shop floor workers and supervisors participated directly in the redesign of the work system, eliminating highly fractionated and monotonous jobs by creating multi-skilled teams, increasing their autonomy and responsibility for decision-making. Even though this program was economically successful—it improved productivity and reduced absenteeism and operating costs—corporate senior managers resisted and withdrew their support. At first, this puzzled me. Why would managers pull the plug on experiments that were improving the bottom line? The answer was simple: power. Shifting actual power, authority, and decision-making down to workers was just too much of a threat to traditional managerial authority.

Similar efforts had been thwarted by management before. Just a decade earlier, a Gaines dog-food plant (owned by General Foods) in Topeka, Kansas had been designed from the ground up with self-managing teams at its core. Under the “Topeka system,” team members were even making hiring decisions (normally the purview of the personnel department). The plant saw initial successes: a 10-40 percent reduction in operating costs; reductions in turnover (to less than 1 percent) and absenteeism (to less than 2 percent); high levels of job satisfaction; and “exemplary” safety. Yet the program was seen as an existential threat to senior managers and corporate staff, who rationalized it as a fluke, an idiosyncrasy of Topeka which would never work at other plants. As one reader of the socialist publication Monthly Review noted in a correspondence in early 1978, Business Week ran a March 28, 1977, article entitled “Stonewalling Plant Democracy,” which described management resistance to the Topeka system: “The problem has not been so much that the workers could not manage their own affairs as that some management and staff saw their own positions threatened because the workers performed almost too well.” Another insult to management was that, wishing to share in the company’s financial success, the employees proposed voting on their own pay raises and demanded bonuses. Clearly, the Topeka experiment had gone too far for management. A line in the sand had to be drawn: increasing employee involvement and participation was one thing, but the ceding of power and authority was quite another. As one Topeka plant worker put it, “There were pressures almost from the inception, and not because the system didn’t work. The basic reason was power.”

Masking Managerial Power

Managerial power is seductive. Studies have found that subjects under the influence of power become more impulsive, less empathetic and able to put themselves in someone else’s shoes, and less risk-aware. The intoxication of power is so pronounced that it resembles the effects of a traumatic brain injury, as reported in The Atlantic article “Power Causes Brain Damage.” We probably all know someone who is a decent and affable person outside of work, but put them in a position of power, and all bets are off. The same goes for coworkers or peers who are suddenly promoted; put on their manager hats, and their inner tyrant is unleashed.

Tracing the etymology of the word “manage” reveals an asymmetry of power. In French, the word manage is derived from manège, the handling and training of horses, and manier, to handle. And in Italian, mano, means hand, and maneggiare means the handling of a tool or training of a horse. To manage means having power over. Managing an unruly horse requires exercising the use of physical power over the animal, not unlike the violent use of militaristic force over striking Pullman workers.

Since the era of mass production began, managerial power has found more sophisticated ways of optimizing employee commitment and productivity. The ultimate aim has never changed—that of maintaining power and control over employees. What has changed is the way managerial power is masked through political persuasion and double-talk. Much of the triumph of managerialism is due to persuading workers of the idea that they—not managers—have the power to get the job done. Managers don’t wield power, they lead, facilitate and coach.

In his book, False Prophets: The Gurus Who Created Modern Management and Why Their Ideas Are Bad for Business Today, historian James Hoopes clarifies this sleight-of-hand deception:

The idea of bottom-up employee power … has a cultural function in a democratic society at large, which explains why management ideologues greatly overstate it. On the face of it, bottom-up power seems democratic and consistent with America’s historic political culture. When employees bring their democratic values to work, managers assuage their feelings of lost freedom and dignity with the idea that the corporation is a bottom-up organization, not the top-down hierarchy that in reality it is.1

The GE manufacturing and Topeka plant cases not only provided workers the bottom-up power to do their jobs but increased their autonomy and control over decision-making to such an extent that they wanted to grab the reins of power over the workplace. But management did not sign up for a program in workplace democracy; that would threaten their hierarchical power and control, along with the right to hire and fire—the very foundation of the corporate capitalist system.

So how did management create the illusion of bottom-up worker power and convince workers (and the general public) of their benevolence? Enter one of the biggest con jobs in management history: the famous Hawthorne studies and the Human Relations movement they spawned. These studies began in the late 1920s at the Western Electric Hawthorne Works plant, a subsidiary of AT&T located west of Chicago which employed 29,000 workers for the manufacture and assembly of telephone equipment. The story usually begins with the factory Illumination Studies. Hawthorne’s industrial engineers experimented by increasing and decreasing the lighting on the shop floor to determine the effects of illumination levels on productivity. The engineers were surprised by the fact that productivity increased whether the illumination was increased or decreased.

Determined to find the answers to what accounted for the productivity improvements, managers at Western Electric sanctioned what was known as the Relay Assembly Test Room experiments. On the main floor of the plant, several hundred workers produced over 6,500 different relays, with a total annual production of 7 million relays (a key switching device in analogue telephone systems). The assembly of relays consisted of mounting some 35 different parts and was highly repetitive and labor-intensive work requiring manual dexterity.

A special experimental test room separate from the main assembly floor was where six women were put to work. They were in their teens and 20’s and of Norwegian, Polish, and Czech descent. Their productivity, social interactions, and attitudes were closely observed by a piece-rate analyst from Hawthorne’s personnel department. For five years, various experimental conditions were introduced, with varying lengths of rest periods, coffee breaks, and shorter work hours. Productivity increased by 46 percent over the entire five-year period. During one of the later test periods, the women worked as they normally had before the experiment began—without rest periods and midmorning coffee breaks—and returned to their regular hours. In this period, the women broke all previous productivity records on a daily and weekly basis without any drop in output for 12 straight weeks.

Western Electric researchers concluded that no single experimental factor could explain or be correlated directly to the increases in productivity except for one constant: the presence of the piece-rate analyst who observed and recorded the women’s activities. Hawthorne managers hired Elton Mayo, a professor at the Harvard Business School, along with several of his colleagues, as consultants to the project. Writing over a decade after the experiment, Mayo explained the productivity increases as an inadvertent result of the relaxation of managerial control:

The girls claimed that they felt less fatigued, felt that they were not making any special effort. Whether these claims were accurate or no[t], they at least indicated increased contentment with the general situation in the test room by comparison with the department outside. At every point in the program, the workers had been consulted with respect to proposed changes; they had arrived at the point of free expression of ideas and feelings to management…. What actually happened was that six individuals became a team and the team gave itself wholeheartedly and spontaneously to cooperation in the experiment. The consequence was that they felt themselves to be participating freely and without afterthought, and were happy in the knowledge that they were working without coercion from above or limitations from below.

Mayo attributed the supposed lovefest in the test room to the unexpected influence of the piece-rate analyst, whose mere attention to the women, he surmised, caused them to become better workers. Mayo made a concerted public relations campaign, giving talks at gatherings of economists and neurologists, publishing his interpretation in newspapers and journals as well as writing books, and giving radio interviews in which he declared that his groundbreaking scientific discoveries would once and for all solve the labor problem. His story became so popular that in the late 1950s, social scientists dubbed it the “Hawthorne Effect.” But the so-called “Hawthorne effect,” the mere act of paying attention to workers, was not what Mayo was most excited about. Rather, his most cherished revelation was that the researchers had supposedly created a “new industrial milieu,” the recreation of a seemingly Medieval, conflict-free atmosphere where the women’s “social-wellbeing ranked first and the work was incidental.” In other words, the women had come to know their place in the industrial-feudal hierarchy and performed their work without complaint.

A Textbook Case of Misrepresentation

For nearly a century, management and organizational behavior textbooks used in business schools, as well as popular management trade books, have parroted Mayo’s popular account of the Hawthorne studies. Contemporary Management, a widely adopted introductory undergraduate textbook, is faithful to this orthodoxy:

The researchers found these results [the “Hawthorne effect”] puzzling and invited noted Harvard psychologist, Elton Mayo, to help them.… Gradually, the researchers discovered, to some degree, the results they were obtaining were influenced by the fact that the researchers themselves had become part of the experiment. In other words, the presence of the researchers was affecting the results because the workers enjoyed receiving attention and being the subject of study and were willing to cooperate with the researchers to produce the results they believed the researchers desired.

Textbook explanations, such as the one above, would like us to believe that a benevolent and utopian-like work atmosphere had been created in the Relay Test Room. However, absent an actual control group that would have removed the researchers from the test room, it’s remarkable that the so-called “Hawthorne effect” is still considered scientifically credible at all. As Matthew Stewart writes in his book The Management Myth: Debunking Modern Business Philosophy:

Not until independent researchers took a fresh look at the evidence did the extent of Mayo’s fraud become apparent. His posthumous critics eventually described the Hawthorne works as “worthless scientifically” and “scientifically illiterate.”

Even as early as 1949, the United Auto Workers’ monthly magazine, Ammunition, called Mayo and his pro-management colleagues “cow sociologists.” This alludes to the way that contented cows provide more milk, implying that “happy” employees are more productive.

The textbook conclusion seems to not only conveniently ignore this shoddy experimental research methodology, but the depiction that the Hawthorne effect was “discovered” fails to account for the fact that “researcher presence” (code for gentle, relaxed, and humane supervision) leading to happier and more productive workers is a socially constructed myth, an interpretation and claim that Mayo imposed on the data to further his own ideological agenda. (In this way, meaning was not discovered but imposed, as is often the case in the social sciences.)

Mayo was, in fact, a conservative and a demagogue whose beliefs played to the times as an influx of European immigrants working in American factories inspired a fear of a working-class revolution, the “Red Scare.” Just a sample of Mayo’s earlier writings prior to his involvement in Hawthorne include: rants against democracy, socialism, and collective bargaining; quacky notions that the “agitation” of the working-class was due to high blood pressure, neuroses, and irrational unconscious forces; and grandiose promises that only a new industrial psychology could save Western civilization from decay. Given such ideas, one can hardly expect such a right-wing ideologue to have come up with a research conclusion other than the one he did.

Management textbook authors have not only ignored scholarly criticisms of the Hawthorne studies but have conveniently omitted relevant facts and important details about the Relay Test Room experiments that cast serious doubts on the findings and conclusions. Richard Gillepsie’s book, Manufacturing Knowledge: A History of the Hawthorne Experiments, provides a meticulous and rich narrative that is based on original experimental and archival data—and his historical account tells quite a different story from that of the popular version.

Gillespie’s historical reconstruction of the Hawthorne studies shows that it was a highly controlled and invasive experiment that has little resemblance to the stories told by Elton Mayo and his Harvard acolytes. Far from having autonomy over their work, the women in the relay assembly test room were under constant surveillance. The pace and productivity of each assembler was recorded in a logbook every 15 minutes by an observer that sat directly opposite the workbench where the women were seated. (One of the women requested that a screen be placed in front of her workbench to provide privacy from the male experimenter’s gaze.) The observer also methodically filled out a daily history sheet, noting any changes in social interactions or attitudes of the women. The women were informed each day of their output and were threatened with reprimands if their output fell below expected levels. Western Electric researchers also questioned the women about their home lives, families, and social activities, requiring the women to have monthly medical checkups by the company’s physicians. Even the timing of the women’s menstrual periods were known and recorded by the researchers.

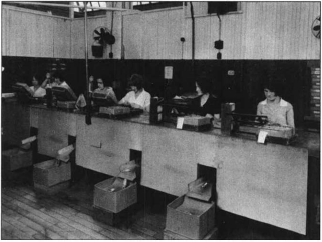

Above: Women in the Relay Assembly Test Room at the Hawthorne Western Electric Plant

Never mentioned are the special economic incentives that were introduced to the six women: they were rewarded for their group output. Prior to the experiment, the women were on a similar group incentive plan except that their earnings were averaged across the main department of some 200-plus assemblers. Under their new piece-rate wage system, any extra effort on the part of the six women would easily increase the amount of money they could earn. Far from being compliant and submissive, some of the women threatened to go on strike when they learned, on one occasion, that there had been a miscalculation of their wages. Even Hawthorne’s test room observer noted in an internal report that “the women had a keen interest in their daily percentages and a much clearer understanding of the piecework system than other workers.”

The women in the relay assembly test room were initially allowed to talk and enjoyed doing so while working, but incessant talking often led to slowdowns in production. The researchers warned the women that disruptive talking had to cease, but two of the women ignored the warnings and were removed from the test room just one year into the experiment, replaced by two new women who had reputations for being fast assemblers—another detail that is glossed over in textbooks, popular books, and internet retellings of this story. And such an incident certainly contradicts Mayo’s assurance that, “At no time in the five-year period did the girls feel that they were working under pressure.”

The Hawthorne experiments, then, have become a kind of mythology that supposedly proves the inherent beneficence of management while ignoring the actual variables at play that influenced the women’s behavior. The women were given more attention alright, but it was in the form of closer supervision and constant surveillance, and, of course, they liked the extra money.

And what about Elton Mayo? Was he really a savior who supplanted the slave-driving mechanization of factory work that took place in the early 20th century (the legacy of Frederick Taylor’s “Scientific Management”) with the communal harmony of good human relations? Mayo, an Australian, has been portrayed as one of the most influential social scientists of the 20th century. But he was a fraud. He misrepresented his credentials under the pretense that he was a psychoanalyst and a medical doctor. A little known fact is that “Dr. Mayo,” as he liked to be called, flunked out of medical school three times, and his terminal degree was a bachelor’s in philosophy. He was even known to fake a British accent to gain favor in social circles and fudged his curriculum vitae in his application to Harvard.

Prior to weaseling his way into Harvard, Mayo held a research associate position at Wharton’s Department of Industrial Research, funded by John D. Rockefeller Jr. himself, whose largess and industrial empire had been built upon a dismal track record of labor relations, most notably the strikes at the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company which led to the infamous Ludlow Massacre, when the National Guard opened fire on striking miners in their tent colony, killing 25 people. Even prior to coming to the United States, Mayo’s skepticism towards democracy and politics had already taken shape, as he looked to big business—monopolistic corporations and a new “administrative elite”—as the linchpins for restoring social order and communal harmony. “Democracy, as at present constituted,” Mayo wrote, “exaggerates the irrational in man and is therefore an anti-social and decivilizing force.” Fervently anti-union, Mayo argued that labor and industrial unrest was due to a “working-class psychopathology,” that workers suffered from neurotic “reveries” and obsessive fantasies because they lost their sense of meaning (resulting in anomie, or a breakdown of social stability) in industrial society. As Gillepsie observed, there is “a persistent tendency in Mayo’s work to transform any challenge by workers [to] managerial control into evidence of psychiatric disturbance.” Interpreting employee defiance in this warped way is reminiscent of the treatment of dissidents in the former Soviet Union who were exiled to psychiatric hospitals for their protests against the Communist regime. Mayo’s quackery went so far as to claim that “industrial unrest” and political revolutions were caused by populations with blood pressure derangements and concomitant “fatigue.” For Mayo, group contagion fueled by irrational behaviors is what led to strikes and class conflicts. Salvation from this rabble lay in training managers to use sympathetic human relations techniques as a psychiatric cure. Who would bring this psychiatric cure? Management.

A sophisticated charm school, human relations has now been rebranded as “leadership training,” a master class in the etiquette of soft power. Managers-cum-leaders practice a dramaturgical performance art, learning to present themselves as an empathic coach, friendly counselor, and a source of moral authority. Just as knights and nobles had to learn courtly social graces if they were to successfully maneuver within the royal court, aspiring managers are exhorted to acquire “soft” skills so they can become enlightened corporate mandarins, emotionally intelligent leaders who have learned the subtle art of employee manipulation.

The Making of the Managerial Caste

Human relations was the wolf in sheep’s clothing that allowed managerialism to spread into every sphere of society. Writing during the Second World War, James Burnham, in his book The Managerial Revolution, foresaw the future as neither capitalist or socialist, but oligarchic—ruled by a professional class of managers. (Concerned with Burnham’s dire predictions, George Orwell wrote a review shortly prior to the publication of Animal Farm.) According to Robert Locke and J.C. Spender, managerialism took shape in the economic boom years of the 20th century in parallel with the growth of business schools. In their book, Confronting Managerialism: How the Business Elite and Their Schools Threw Our Lives Out of Balance, they describe managerialism as:

what occurs when a special group, called management, ensconces itself systemically in an organization and deprives owners and employees of their decision-making power (including the distribution of emoluments)—and justifies that takeover on the grounds of the managing group’s education and exclusive possession of the codified bodies of knowledge and know-how necessary to the efficient running of the organization.

As critical management studies scholar Martin Parker argues in his take-no-prisoners book, Shut Down the Business School, management is “a claim of specialist mastery which implicitly denies that others have that capacity, and is justified with reference to embossed certificates from business schools.” The entire edifice of management rests on the pernicious assumption that only managers have the special sauce, expertise, and know-how for managing; the rest of us minions are deemed incapable of doing so.

Locke and Spender go on to argue that managers have come to see themselves as a professional caste differentiated by their wealth, privilege, and superior educational status. Orwell’s Animal Farm was indeed prophetic of an anti-democratic management caste and their predilection for self-serving double-talk. Noting this, Locke and Spender write:

The management caste, the pigs, have changed the slogan of liberty from “all animals are equal,” to “all animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others”—at least in the workplace, where democracy is meaningful only to the rich and powerful.

This caste mentality is institutionalized in management and organizational behavior courses that are taught to every undergraduate business student worldwide. For example, the textbook Contemporary Management presents managerial power as simply the natural order of things:

They (managers) are the people responsible for supervising and making the most of an organization’s human and other resources to achieve its goals. Management … is the planning, organizing, leading and controlling of human and other resources to achieve organizational goals efficiently and effectively.

This is a conception of management that claims a monopoly on organizations, legitimizing a belief that managers are an absolute necessity and exclusive stewards, not just for corporations but for all areas of society. Managerialism knows no bounds. Whether it be in universities, healthcare facilities (where growth in management jobs is unusually high), NGOs, or sports teams (get a degree in sports management!), managers are seen as indispensable. (According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics, growth in management employment over the next decade is expected to be faster compared to the average growth in all other occupations.) Even Christian megachurches (and their disciples) need to be corporatized and better managed if they are to bring in the cash; luckily the Harvard Business School has a case study (Willow Creek Community Church) for doing just that.

This indoctrination is seductive. Managers are romanticized as a professional class that speak a different language, wear expensive business suits (or T-shirts in Silicon Valley) and sit behind big desks in corner offices, enjoy luxurious expense accounts, and, of course, command much higher salaries. This may be the destiny of students who can afford to attend an Ivy League school. But it’s disingenuous and deceptive marketing when such a proverbial cultural carrot is dangled to incentivize students in state colleges and public universities to pursue a degree in business management when the possibility of garnering such elite privilege is quite remote. (Still, management jobs generally pay well. Labor statistics show that the median annual wage in management was over $107,000 in 2022, which was more than twice the median annual wage for all occupations of $46,310).

An introductory management textbook doesn’t convey the perks that many managers acquire, but that’s where the iconic Harvard Business School (HBS) case studies come in. Shortly after being appointed dean at the HBS in 1919, Wallace Donham, who had trained in the case method at Harvard’s law school, championed the case study method as a way of professionalizing the business curriculum. The Harvard case study was marketed as a “problem-centered” pedagogy, superior to rote textbook learning and abstract theory. “Real world” business problems and challenging scenarios from actual companies were presented in published cases, requiring interactive class discussions and analysis of facts. To this day, HBS case studies are still considered the pedagogical gold standard in business school curricula. In 2022, Harvard Business School Publishing sold over 16 million cases, accounting for 80 percent of cases used at business schools worldwide.

A typical management case study is a 10-20 page pamphlet that tells a story about a heroic CEO, (aka) a “transformational leader” of a Fortune 100 company who successfully changed the corporate culture, or some Wall Street darling turn-around artist who “strategically” downsized a firm. Students are cajoled to imagine themselves as the protagonist in the case, playing a make-believe game of “what would you as the CEO do in this situation?” One of the popular cases I had to use when I taught the case studies (which I detested having to do) was that of the late Jack Welch, CEO of General Electric, once known in the press as “neutron Jack” for his mass firings and plant closures. I felt a debilitating cognitive dissonance. Here I was, teaching about The Glorious (Asshole) Jack—to mostly first-generation college students who were probably, at best, likely to rise to the ranks of middle management or end up working in some back-office cubicle at an insurance company.

The lionizing of American CEOs in HBS cases reads like hagiographies of Christian saints. CEOs are trotted out as “leadership” role models students should emulate. And the case studies also promote the idea that, because these leaders have entitled and elevated positions in the corporate hierarchy, they should be paid more—indeed, a lot more. According to the Economic Policy Institute, as of 2022, CEOs were paid 344 times as much as the average worker. Unsurprisingly, a search of the HBS’s extensive catalog results in only one case, from 2019, “Income Inequality and the CEO Pay Ratio at TJX Cos,” that acknowledges “concerns” regarding income inequality. In this case, it’s a CEO-to-worker pay ratio to the tune of 1,596-to-1 and CEO Ernie Herrman’s $19 million salary. (Herrman is credited with steering “the company through the tumultuous retail environment.”)

The HBS case studies probably ought to be thought of as a form of propaganda. In 2016, management professor Todd Bridgman of Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand and colleagues published a “counterhistory” of the case method, looking deeper into the ideas of Wallace Donham. Some years after introducing the case studies, according to one summary of the paper in Quartz by Lila MacLellan, Donham actually “sincerely believed [the case studies were …] too indifferent to larger societal ills, too insensitive to the labor market, and thus to economic prosperity and equality among workers.” MacLellan notes further that the case method has been “knocked for several serious moral failures,” including mythical portrayals of CEOs and senior management and the exclusion of the voices of women, the poor, and laborers. Bridgman believes the method has “tainted business education, leading people to believe […] that business schools exist simply to ‘reproduce capitalists.’” Case closed!

Office Feud(alism)

There are more than 16,000 business schools worldwide, and business is one of the most popular undergraduate majors in the U.S. It’s no surprise that we have become an over-managed society where a professionally-trained managerial class has taken on a life of its own. Management has spread like a malignant cancer, proliferating through middle-level layers, making Kafkaesque organizations and justifying the call for more managers with spurious titles. This oversupply of managers requires the creation of work to keep them busy, which is one reason there are so many soulless, torturous, and frivolous meetings. Managers infected with the power bug crave a captive audience where they can strut their authoritarian feathers to remind us just how busy they are.

But that’s not all. David Graeber argued that corporations (and increasingly bloated university administrations) operate more as feudal estates than “lean and mean” profit machines. Feudalistic managers keep their minions busy by generating a barrage of often unnecessary busywork—filling out bureaucratic forms, circulating memoranda and needless emails, wasting valuable time on wordsmithery in crafting meaningless mission and values statements, demanding useless reports, tedious assessments, and audits, mandating mind-numbing training courses, and then cajoling everyone to be a “team player.” The presence of managers who revel in dishing out these mindless tasks—who Graeber called Taskmasters or Box Tickers—is a definite sign of what he would call a “bullshit job” kind of situation, one in which managers or their subordinates might consider their duties more pernicious than useful to society, or just plain useless. But many managers would probably never admit this.

One critical aspect of what Graeber called managerial feudalism is keeping the worker tethered to their desk. The modern corporate-feudal estate pays for a full-time, 9-to-5 employee whose physical presence at the office is not only supposedly essential for operations (or “spontaneous collaboration”!) but whose fealty is expected at all times. The Covid pandemic wreaked havoc on this arrangement. The pandemic created a large, sudden experiment for many companies, especially those in the financial, scientific, and IT industries, whose employees (sometimes nearly all of them) were suddenly working from home. Yet work was getting done without compromising quality or productivity, often in less than eight hours, and in between dog walks, childcare, and baking bread, even with some employees starting side hustles. And yet, according to the Society for Human Resource Management, and as reported in the BBC article, “What Bosses Really Think About Remote Work,” “a whopping 72 percent of managers currently supervising remote workers would prefer all their subordinates to be in the office.” No surprise, then, that many companies—including the big tech hipster firms Google, Meta (formerly Facebook), Apple, and Amazon, the early pandemic adopters of remote work—started demanding employees come back to the office. Even managers at Zoom, the remote video conferencing company which facilitated remote meetings for over 300 million people a day during the pandemic, have demanded their local Bay Area employees return to the office, citing a need for a “structured hybrid approach” that keeps “teams connected and working efficiently.”

This corporate flip-flop probably has something to do with a managerial lust for corporeal power. (Can you imagine the tutelary and quintessential corporate manager Don Draper of Mad Men getting his power fix over Zoom?) With remote work, managers lose the potency of their status differentials and all the informal cues that signal their rank, like telling a subordinate who sits in a cramped and noisy open-plan office or dehumanizing cubicle to drop by for a “chat” in the boss’s plush corner office.

It took a severe economic depression to expose George Pullman’s true colors, showing that his Pullman Town had nothing to do with industrial betterment but with ownership and control of his employees. It’s not all that different from Google’s corporate headquarters—the 2 million square feet “GooglePlex” in Mountain View, California, which was designed to feel like a university campus catering to an employee’s every need. It has organic vegetable gardens, dozens of high-end eateries with a variety of ethnic cuisines, free cooking classes and laundry rooms, numerous gyms, swimming pools, and other recreational facilities, mindfulness and yoga classes, massage therapists, free bus shuttles, and Talks at Google featuring influential thinkers. Google also offers a $99 company hotel room on-site as a perk to help employees transition to a hybrid work schedule. Why should an employee ever go home? This total captivity reminds me of the ad tagline for the Roach Motel: “roaches check in…but they don’t check out!”

The business school is a powerful global institution that deserves much of the blame for producing a power hungry, professionally-trained managerial class. Business schools are also responsible for perpetuating the ideology of what is called managerial capitalism. Managerialism’s prime concern, as Thomas Klikauer explains in his book, Managerialism: A Critique of an Ideology, is that “both [capitalism and society should] mirror the way corporations are managed.” In a society organized according to corporate logic, groups and institutions will essentially function to achieve endless growth and profitability—the mandates of all corporations. As economic anthropologist Jason Hickel has explained, “under capitalism, ‘growth’ is not about increasing production to meet human needs. It is about increasing production in order to extract and accumulate profit. That is the overriding objective.” Such profit, he explains, only comes about through human exploitation and massive natural resource extraction—which is simply not sustainable ecologically.

Because managerialism has spread so thoroughly into society, its effect has been to anesthetize everyday life to the point that many people cannot envision an alternative way to organize themselves. “Any serious opposition to managerialism” has been “annihilated,” writes Klikauer, who poses an uncomfortably poignant question: without alternatives to managerialism, will “global warming, climate change, corporate environmental vandalism, resource depletion, and the passing of peak oil [production …] wipe out the human race?”

The servitude to managerialism shapes the hidden curriculum across all B-school disciplines—whether it be finance, economics, management, marketing, international business, and the decision and information systems sciences. So long as the codependent relationship between business schools and the corporations and elites who have a vested interest in maintaining a society that operates according to “market” logic remains intact, the business school will, as Martin Parker has warned, remain a “dangerous institution.” It’s especially dangerous because its primary mission is to maintain the status quo, perpetuating the belief that there is no alternative to managerial capitalism, which is why the business “academy” is nearly void of any critical scholarship and independent thinking. Until this take-for-granted ideology is seriously challenged, business schools will remain the temples of capitalism, indoctrinating students into the liturgy of corporate managerialism so that they, the ordained dutiful servants of power, remain faithfully committed to maintaining the status quo.

Shut it Down

Uncoupling the business school from the tight grip of capitalism seems like a Quixote-like challenge, but there are ways forward. For these points, I have drawn liberally from Martin Parker’s Shut Down the Business School, as well as my interview with him, for inspiration.

First, business schools need to relinquish their cultish loyalty to the idea that corporate managerialism is the only viable way of organizing human beings. I don’t mean we ought to continue the many failed attempts to “reform” business schools. Rather than trying to put lipstick on an elite pig, we need to do a complete overhaul and reinvention, cutting the umbilical cord to managerialism. This means educating organizers, not managers—creating, as Parker calls for, new “schools for organizing.” The broader purpose of such a progressive education would be to engage students in the struggle to organize a democratic society, offering a vigorous critical pedagogy that doesn’t pander to market logic. Certainly there are plenty of ways of organizing people in ways that are more fair, equitable, and humane than the corporate way. A broad education would expose students to alternative forms of organizing, such as worker-owned cooperatives, mutual aid organizations, local and decentralized economies that do not exceed the ecological carrying capacities of their bioregion, trade unions, gift economies, tribal direct democracies, commoning, anarchist communes, self-organizing and emergent organizations during natural disasters—not to mention what could be learned from history and anthropology.

Second, business schools need to stop perpetuating the myth of the “student as customer.” In the case of education, the customers aren’t “always right.” Indeed, they are often ignorant of what they need to know. Why pursue a degree if you already presume to know the subject matter? Moreover, the “student as customer” is an insidious and misguided adage that frames undergraduate education as a utilitarian and marketable commodity. This tail wagging the dog, sheep-like mentality has led to an overly narrow focus on teaching “skills” and “competencies” that students need as their ticket to a job. In this sense, business and management education is nothing more than a vocational feeder school for entry-level corporate jobs. (For all the big talk of the “student as customer,” business schools seem to be tone deaf when it comes to the fact that the majority of Gen Zers distrust capitalism, with 54 percent harboring a negative view in 2021.) This kind of business education produces, as Max Weber wrote in his famous lament, “specialists without spirit, sensualists without heart.”

Is it any wonder, then, that business undergraduates and MBA students are the biggest cheaters in the university? Monkey see, monkey do. Business schools transmit an ideological commitment to the “bottom line,” and some students may learn that success means doing whatever it takes to get the job done—even if that means cheating. And the growing push among business school professors to simply count the number of publications in peer-reviewed journals as a metric to earn accreditation or simply for reputation-building creates incentives for publishing fraudulent research. It’s beyond ironic that behavioral economics professor Dan Ariely of the Duke Fuqua School of Business and Harvard Business School professor Francesca Gino, both of whom are well-known academic superstars for their research on honesty and cheating, were accused of fabricating research data.

Finally, business schools need to honestly acknowledge that they have become willing handmaidens in the destruction of our planet—even as they claim to be working to address the problem of climate change. Efforts to make business studies reflect “sustainability” never lose sight of, as Andrew Hoffman, a professor of sustainable enterprise, writes in the Financial Times, “the bottom-line,” “the business case” or the opportunities of gaining “market advantage when addressing climate change.” And while 800 business schools have jumped on the sustainability and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) bandwagon, these programs are, at best, impotent Band-Aids, and at worst mere window-dressing and fashionable marketing ploys for recruiting prospective students. Humanity faces impending climate collapse; massive inequality; the weakening of democracies and the growth of ideological extremism; food, water, and energy shortages; civil strife and unrest; forced mass migrations; and financial instability—all of which contribute to people’s deteriorating mental health and well-being. “Sustainability certificates” and other tweaks to existing curricula hardly measure up to these challenges.

Business school professors need to stop fooling themselves and wake up to the stark truth that their profession is part of the problem. As Hannah Arendt wrote, “the sad truth of the matter is most evil is done by people who never made up their minds to be or do either evil or good.” Absorbed in the ideology of managerial capitalism, far too many business professors are, to use Arendt’s expression, “terrifyingly normal,” career complacent and self-satisfied, deluded into believing that by publishing obfuscatory, theoretical, and abstract twaddle in pseudoscientific peer-reviewed journals (that only a handful of other academics read) from their lofty perches they are making a real-world “impact.” Most business academics that I know have buried their heads in the sand, cordoning off their personal values, moral conscience, and ethical concerns. This strategy of avoidance, of course, only exacerbates faculty stress and alienation. (I know, because I have been one of them.) Those professors who wish to defect need to do an about-face and become engaged public intellectuals, refashioning themselves as voices of resistance.

Schools of organizing may sound utopian, but this is actually a good thing. “Oppositional utopianism” as critical education scholar Henry Giroux advocates, is the antidote to managerial capitalism. But it’s highly unlikely that business schools in the U.S., given how entrenched they are in corporate stewardship, will lead the way. It’s much more likely that schools of organizing will take root in social democratic countries which have already laid the foundation for such change. They’ve learned from the industrial democracy movement in Western Europe, which sanctioned the legal rights of employees to participate in decision-making and corporate policy-making affecting their employment, income, and quality-of-work life, along with the power to give or refuse their consent on workplace changes—what was often known as “co-determination.”

What, then, can U.S. business professors suffering from Stockholm syndrome do? They might start by taking a good hard look at their diploma—a Doctorate in Philosophy. That’s philosophy, not ideology. Yes, philo-sophia, which, for the ancient Greeks, is the love of wisdom. Philosophy differs from ideology as it’s concerned with the formation of character, engaging in the discipline of inquiry, posing critical questions, and interrogating history—rather than merely informing or indoctrinating. It’s rare to find this sort of philosophical professing in the business classroom. Are business students exposed to the history of labor movements or how American capitalism was built on the backs of enslaved workers on the plantations? Do accounting majors learn that Excel spreadsheets have their roots in American slave-labor camps? What about finance majors? Do they get to debate the merits of economic rationality, the dominant, “value-free” and morally bankrupt economic theory which contends that actors behave in rational and efficient ways by maximizing their own interests, even if it means lying, cheating, or stealing in order to accumulate wealth? Are students challenged to pose critical questions about managerial power and the legitimacy of oligarchic corporations? Of course they aren’t. “Managerialism as an ideology,” Klikauer laments, “does not serve truth but invents knowledge in the service of power.” And as Loren Baritz concluded at the end of his timeless 1960 book, The Servants of Power, the willingness of business professors “to serve power instead of mind” makes them “a case study in manipulation by consent.” So the question remains. Which master will business professors continue to serve, managerialism as ideology or the philosophy of organizing? For the sake of the human species and the planet, let’s hope it’s not the former for much longer.

-

Explaining workplace democracy, or “industrial liberty,” James Green, author of The Devil of Here in These Hills, a book about labor conflict in coal mining, notes: “The great social dilemma, as Louis Brandeis, the great people’s lawyer, said […] was the question of industrial liberty. American workers left the Constitution behind when they went to work in a steel mill or a coal mine. They couldn’t stand up and give a speech against the boss. Was this an American way? Or should workers be allowed to bring the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, into the workplace? And Brandeis, of course, felt that they should, and that there should be something called industrial democracy or industrial liberty. And that sort of highlighted the fundamental clash of the era.” Marvin R. Weisbord, in Productive Workplaces, asks: “Does it startle you that workers have low commitment to workplaces where they have little to say about their jobs? […] [W]ere we socialized to [expectations of worker productivity] from kindergarten on, studying the exploits of America’s founders? Is it surprising that the central issue of productivity has often been framed as the tension between authoritarian and participative leadership? That’s how American revolutionaries defined their conflict with crazy King George III. The fact [is] that free expression, mutual responsibility, self-control, and employee involvement in work design are associated with higher output, lower stress, and more viable businesses….” ↩