What The World Looks Like to the Super-Wealthy

Michael Mechanic, who has studied the lives of the super-rich, talks about strange bubble inhabited by the 1%.

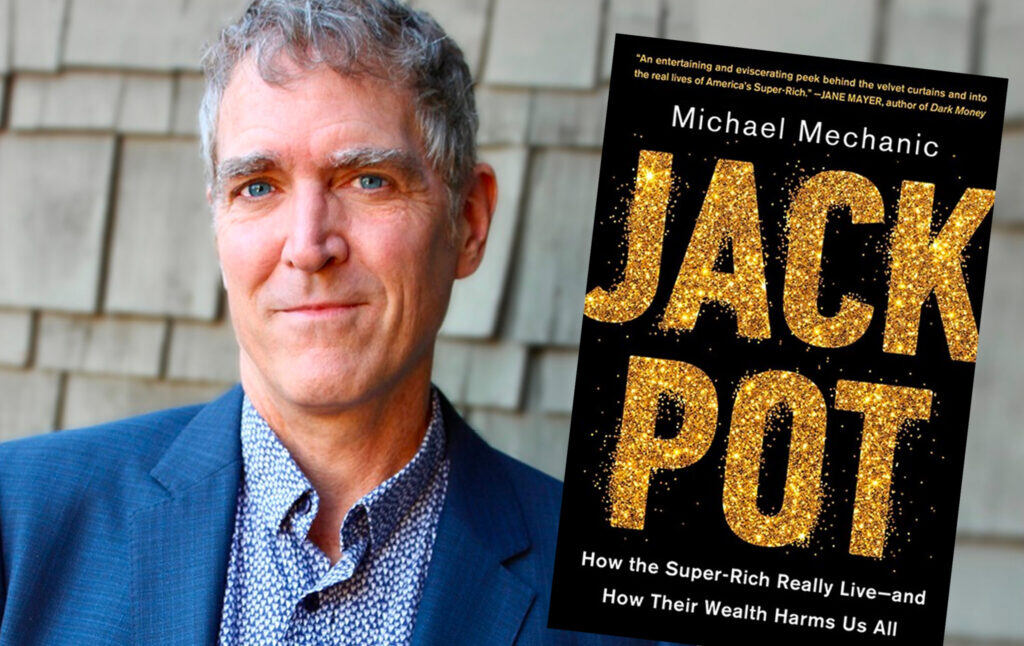

Michael Mechanic is a senior editor at Mother Jones and the author of Jackpot: How the Super-Rich Really Live—and How Their Wealth Harms Us All. Michael’s book goes beyond quantitative statistics about inequality to take a close-up look at the actual lives of the American oligarchs. He joined Current Affairs editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson to discuss life inside “the bubble” that the super-wealthy inhabit—why they ceaselessly pursue endless accumulation, how they rationalize their privileges, and how they rig the system to make sure they never lose any of their dubiously-acquired gains.

Nathan J. Robinson

Your book takes us inside a world that most of us will never get to see the inside of, that is to say, the world of the super or uber wealthy. So, tell us, how did you pry open the door? What did you do to try and get an inside look at the world that is often discussed, but rarely seen, this world of the super wealthy?

Michael Mechanic

I pried into it painstakingly. Not being from that world, one cannot just cold call billionaires and say, talk to me about your money. Nobody likes to discuss their personal finances. It’s taboo in our society. So, it requires a lot of legwork, working from the outside, talking to people who are in the circles of very wealthy people. And in fact, there’s a lot of stuff that you just have to glean from those interactions because there are some people, of course, who won’t let you get anywhere near. I wrote in the book about the frequency of rejection. You have to go into with a list of targets, so to speak.

I had a big Google doc full of targets, and like I said, you can’t cold call them. So you have to find somebody who knows them, and then get an introduction. And even then, you will often have to go through different layers of the entourage that very wealthy people have around them, whether it be financial or public relations, or through a company or whatever. And it’s very hard to penetrate. You can penetrate it when you want to discuss their business acumen, or how great their philanthropy is. But when you want to ask hard questions that get very personal, about their wealth and their interactions with the world, it’s rare that you can find people willing to reveal their feelings. They feel very vulnerable.

Robinson

When people hear, “Would you be willing to talk to a journalist from left-leaning muckraking Mother Jones magazine for his book on how the super wealthy’s wealth harms us all?” I imagine many people shut down. But yes, there’s this uneasiness or anxiety. You talk to people in the book who feel kind of guilty about their wealth sometimes. Tell us about the unease that comes with the possession of vast wealth.

Mechanic

There are plenty of anxieties related to wealth because we think about the way the world perceives us. As you move up and become more of a public figure, in a way, you’re more visible to people when you have a lot of wealth. There’s this perception that this person isn’t authentic, they’re not down to earth, or they don’t experience the world the way we do. And actually, there’s a lot of truth to that. Unless you somehow can hide your wealth and live in a normal mixed wealth, middle class community, most very wealthy people want to enjoy their wealth in some regard. And often they want more space. It’s the usual reason people flee cities for the suburbs. They want more space, they want better schools, like the white flight thing, but there’s a wealth flight as well. And as you know, they’re partially the same because most very wealthy people are white, but there is a fleeing of mixed wealth areas for wealth havens.

So, you get areas where people are geographically separate from the rabble, and on the other hand, you have very concentrated areas of poverty and mixed wealth areas shrink. And so, you have this great distance between the rich and the poor. You see the same thing with CEOs and workers over the decades: the distance between them financially has gotten so extraordinary that you would never find them living in the same neighborhood ever.

Robinson

That’s interesting because it helps to explain something that seems at first to be a little bit of a paradox, which is that a number of the super wealthy seem not to desire fame, in that they want to lie low. This Harlan Crow guy, the friend of Clarence Thomas, was horrified to be dragged into the public eye. Because everyone recognizes that the pitchforks might come for them—if only on Twitter—if they become a public figure. You can be resented and despised. But at the same time, I say there’s a paradox because you also write about conspicuous consumption and the way in which status is expressed through the possession of things that are displayed to others. You quote Karl Marx talking about when the palace arises next to the little house, the little house turns into a hut. It’s the idea that one’s status is in part determined by how one looks standing next to other people, but at the same time, you don’t want to be too public, or else you might attract undue attention. Can you talk about that mixture of the desire to be seen and not seen?

Mechanic

We all compare ourselves to our peers: people in our professions, people close to us, people at our churches—the people in our circles. There was another quote that says the beggar doesn’t envy the billionaire, they envy the beggar with the better panhandling area or whatever. So what happens is even when people do segregate themselves by wealth, there’s still this competition—the fancy Joneses, so to speak.

There have been studies about this. If you’re living in a wealthy area, and you’re in the top 10% of the house distribution, essentially the high-end houses within an area, as the house sizes get bigger, you become less satisfied with your lot. So there really is a lot of social comparison, when you move into what I call the bubble. You go to the party, and this guy is talking about his private equity deal, and this guy’s talking about his private jet, and this guy about his new Bugatti and his house in Aspen. People socialize, and it’s not always that blatant.

But the way we talk to each other, it’s like, “Where do your kids go to school? Mine go to Yale and Harvard,” as opposed to the University of Florida. These things come out in social situations, and the more you’re segregated into a bubble of wealth, it normalizes these things that are actually very weird. And the idea that you are on a private jet, it’s kind of crazy. And it’s terrible for the planet, by the way.

Robinson

Yes, I wanted to ask you about the weirdness of this world. I’m sure you discovered during your research things within this world that you didn’t realize existed, or that makes sense for people to buy when they have a lot of money. For me, when reading your book, you write about concierge doctors, and about how there are doctors where you don’t sign in and don’t wait.

Mechanic

They don’t see any other patients. You walk in, get your cucumber water, and they say, “Hi, Jim. How’s your kids?” They know you and know what you do, and they ask you about your business. They time it so you actually never see another patient, because who wants to mix with other people?

Robinson

Yes. Were there other things that you found where you thought “I have not heard of that”?

Mechanic

Well, a lot, in fact. It’s not just stuff but services. You hear more about these every day. I was just reading Timothy Noah at the New Republic. Timothy Noah has done a lot of work on inequality, and he was just reporting on something called a top hat pension, which is a way of giving incredibly large retirement savings to CEOs. This is money that comes directly out of the big companies’ pool that could be lifting the lower workers’ salaries or giving them better retirement benefits. It’s about the deterioration of a company pension. And now it’s like 401Ks. So, maybe if you’re lucky, they’ll give some kind of match, but most companies don’t. Meanwhile, for their executives, they have this high-tier retirement savings. Retirement savings is something I didn’t write about in the book, but I’ve since done a lot of research on, and it’s very heavily federally subsidized. It’s very skewed toward the wealthiest. It’s quite incredible how much it costs. We’re talking about, over five years, almost 2 trillion in tax breaks. That’s enough to fund Biden’s Build Back Better package that got rejected. We think about the welfare state, and we think about poor people, but it’s actually wealthy people who are getting most of the benefits flowing from the federal government.

Robinson

What do you think are some of the more unfair or unjustifiable legal structures or pieces of policy that really maintain extreme inequality?

Mechanic

One thing you see is, you can debate the role of estate taxes—they were first enacted to pay for wars back in the day, and then they would be repealed. But ultimately, when you think about the goal of the founders of America, we were not to be an aristocracy. We were trying to escape this whole feudal state where the rich people controlled everything. It was supposed to be a republic, controlled by the people, to some degree.

Obviously, it’s a mixed bag the way they set it up. I write about this debate between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, and Thomas Jefferson was arguing that the aristocracy was going to go away in the new republic, because of the availability of land, and we’re getting rid of all those hereditary laws in England that gave the property to the firstborn son, and all these types of things. He said, this will be this beautiful equal opportunity place. But over the years, the way our tax code has been sculpted, it allows money to accumulate in families and continue to accumulate and accumulate.

There are all these legalized trust structures that have come about, and these are things you would never hear about, unless either you are really interested in digging and read about it, or you have the money such that you would actually consider them. If you look at the current lifetime exemption from gift or estate taxes, meaning the amount of money you can give your kids tomorrow without paying any taxes on it, it’s about $26 million—a couple could give their kids that much money without paying a dime. Then beyond that, there are a million little ways to move money around, put it in different types of trust structures, to essentially over the generations create dynasties, and we’ve had a growing number of these in the United States. Dynastic wealth was never an American ideal, but it’s become an American reality.

These dynasties have incredible political power. They’re trying to repeal the estate tax, they’re funding anti-minimum wage, all this stuff. So you can always talk about how their wealth harms us all. Dynastic wealth is used to generate more wealth. It’s funny because people always bring up Warren Buffett. He’s a good guy, humble, and modest. Well, he partakes in all of these advantages, even though he says, “tax me more.” I guess that’s understandable. These guys say, I think the rules are unfair, but I’m going to play by the rules that we have because why should I not? I’m not just going to hand money to the government that I don’t have to, but you should change the rules.

But then, behind the scenes, these very wealthy folks hire all these money managers, Wall Street banks, and so forth. Those guys are doing the lobbying behind the scenes to keep all the perks. So it’s really hard to go out there and be the good rich guy and say, tax me more, when you know that the people who are managing your wealth, are lobbying—

Robinson

Making sure you don’t have to be taxed more.

Mechanic

I’m not saying they don’t have good intent. They might really believe that. But the fact is, unless you have an independent wealth manager doing everything to your liking, and maybe not taking advantage of every last possible way to get around taxes…. One thing I talk about is how the wealth is overwhelming. It’s like trying to manage it yourself, forget it. You have other things you want to do in life than sit around and deal with the mind-numbing arcana of trusts and estate law, so you hire people, and the default in the industry is to maximize wealth and minimize taxes.

Robinson

You’ve just touched there on the ways in which the super rich actually affect policy. You have this quite striking question that you ask in the book, which is whether you can get your congressman or a senator on the phone, whether you’ve interacted with them or can interact with them personally. And the reader might think, “Of course I can’t.” But you point out that the answer to that question is entirely dependent on how much wealth you have, because it is the case that there are plenty of people who can actually talk to their elected representatives.

Mechanic

Right, and who maybe help them become elected representatives. People of the Harlan Crow ilk have enough money that they can actually have a big impact on who gets elected. With Harlan Crow and Clarence Thomas, they say, Crow hasn’t had any cases before the court. But the thing is, Harlan Crow is a huge Republican donor; he is in the business of political influence, essentially. And Clarence Thomas has not recused himself from any of these cases that would allow Harland Crow, for instance, to make massive political donations and keep them anonymous, like Citizens United and various other things that open the floodgates to money coming in from the rich and corporations.

I talked to a guy recently, a psychologist at Berkeley, who wants to write a book and wanted to talk to me about it. He was making the point that the founders came up with all these checks and balances so that one part of the government didn’t get too out of control. There was always a way to rein them in, he said. But what they didn’t take into account was the accumulation of wealth and how that was going to affect the whole government system. So essentially, this is a fifth tier. You’ve got your branches, then you got journalism trying to keep things in check. And then you have this gigantic pile of money over here that’s going to have its way and there’s nothing to keep a check on that.

Robinson

The Crow thing has been quite fascinating as a kind of peek inside how power really operates and who has it. All the arguments that are made in Thomas’s defense are in the cases he didn’t change any votes. But gosh, I wish I could just call up a Supreme Court Justice and tell them what I think about things. I think you just have to get a yacht and a nice plane and offer to take them someplace.

Mechanic

Also, Clarence Thomas—I think that famous painting might have been at Bohemian Grove. I know a Supreme Court Justice will go to Bohemian Grove, which is this haven of the rich and powerful here in California. It’s an exclusive club, both in San Francisco, and then they have this place out in the Redwoods, which is very hard to get into, kind of like Burning Man for the extraordinarily rich, where people have their encampments, sort of. And I think even probably within Bohemian Grove, you have to know the right people to get invited to the right parties with it, but there’s a lot of mixing.

That’s another thing about the bubble I talked about, the wealth bubble also crosses over to influence. When I talked about geographical segregation of rich and poor, one thing that the concentration does is it propagates both advantage and disadvantage. So if you are living in a community of very wealthy people, and those are the people you interact with socially, you’re just going to have a lot more opportunities for cross pollination. If you have a business venture, you’ll find people to partner with and to put money into your business venture. If you need connections so you can raise money to start a company, you know this guy who’s part of this venture fund. These sorts of connections, when you have mixing of wealth, actually has been shown to provide a lot more opportunity for people for social mobility. You don’t get that when you have the segregation.

Robinson

Tell us a little bit more about what you discovered about how money works in politics. You talk to a congressman in the book about how lobbying actually works. What did you discover about how the sausage is actually made? You’ve talked about how there’s all these interests in keeping the tax code favorable and keeping policy structured in a way that perpetuates dynasties. But what is it that money does to ensure the correct political outcomes?

Mechanic

Both ensures that people can get reelected. Members of Congress serve very short terms, and they’re always fundraising all the time. There’s no end to it. The maximum that you can give to a given person, I think for couples, is $5,800 now. That’s the maximum that they can technically ask for, and you can give unlimited money to a political party. And so, there is a temptation for members of Congress to also raise money on behalf of their party because that gives them power within the party.

I talked to Russ Feingold, who was part of the McCain-Feingold finance reform. He’s no longer in office, but he had a lot to say. He’s very frustrated to see his signature achievement be torn down. He says it’s worse than ever, worse than it ever was now with the Supreme Court, bit by bit, chipping away at everything he had achieved as far as campaign finance reform. So he was pissed off.

I talked to Tom Malinowski, who was a New Jersey congressman, and he actually just recently lost his seat because they redistricted. He got a raw deal. He used to be a lobbyist for Human Rights Watch, and so he says, “I don’t have any problem with lobbyists, I used to be one. We have a right to go in there and try to affect policy. It could be for good, it could be for ill.” And he says, “So I let lobbyists come to my office and talk to me. Sure, no problem.” There is that access thing, once you’re in the door, that’s when these things start happening.

But the problem is, when you mix lobbying with fundraising, there’s almost never directly a quid pro quo. But there’s always sort of an understanding. It’s like, you hear my point of view, we’re going to give this money, and keep it in mind when you’re voting. It’s very rare that you can catch somebody in the act of, I’m going to give you this money for this vote—it just doesn’t happen anymore. At least, that we know of.

Robinson

But everyone knows that if they started to act differently and sound more like Bernie Sanders, the checks can stop coming very fast.

Mechanic

I think about Senator Manchin and Senator Sinema. Kyrsten Sinema, in particular, kind of got in bed with these private equity people, and she would not vote to get rid of carried interest, which is an absurd thing. Private equity people are paid enormously well as it is. They raised hundreds of millions of dollars from institutional investors and take a big annual fee. They make these sorts of years-long investments in whatever it happens to be that they specialize in, and the way it works is called 80/20. So they promise that if the thing succeeds, the investors get at least a base return of 8% or whatever, and then anything above and beyond that is split: 80% for the investors, 20% for the fund managers. So in addition to the fees they charge, they’re getting a huge payback. When things go well, which they often do in these cases, private equity is very lucrative. Sometimes in real estate, they’ll pull out all this money from loans, they’ll put the thing in debt, take out all the money up front, pay everybody off, and then it’s nothing but upside for them.

So the question is, how do you tax that money? Well, they’ve managed to convince the government to tax it as capital gains at 20% as opposed to wages at 37%. That’s a ridiculous tax break. In fact, one thing I just don’t understand—I’ve never heard a good rationale for it—is if you tax investment gains at the same rate, why don’t you tax investment gains at the same rate as wages?

So if I’m a rich guy, and I have $50 million free cash, and I put it in the stock market, the stock market goes up, and I sell that stock. I’ve done nothing, except had a bunch of money. And my tax rate for that money is much lower than if I had worked for that money. I think that rubs a lot of people the wrong way. I ask people, so what’s your rationale for that? They say, you got to incentivize people to invest and whatever. Come on, man. Are you going to put the money under your mattress? You have to put it somewhere. Are you going to put it in the bank at 2% interest? No. They don’t want to sit and watch their money incrementally grow, they want to get another big payback. They have hit the jackpot once, and they want to hit it again.

Robinson

Sinema is a very clear example of the direct policy consequence of an interest group that wants to preserve a policy that makes absolutely no sense, except on the justification that this particular group would like to stay very wealthy.

Mechanic

Yes, they really schmoozed with her. Maybe they showered love and affection. Everybody wants to be recognized and loved, and it’s the same with rich people and politicians. And I think a little love goes a long way. In writing about the anxieties of the super rich, there’s actually a lot of loneliness because there’s so much social isolation from being wealthy. People do it deliberately because they live in some big house that’s far from the other houses, and they limit their social pool because they don’t trust people as much. There’s definitely a lack of trust. It’s like, if somebody comes to me, is it in friendship because they like me, or do they see that I’m wealthy and want a piece?

Robinson

You can’t trust anyone anymore because everyone wants your money.

Mechanic

It’s a really unfortunate position to be in, especially if you’re a billionaire. Everybody who comes at you wants something—everybody. Even just to be in their circles. I talked to a guy who made his first smaller jackpot working at Microsoft. He was like an early employee, and he later became the president of a dot com era company, and that went crazy in the stock market, and he made another big fortune.

He talked about the friends of Bill Gates, the people who had access to Gates’s inner circle. There was a social cachet to being friends of Bill, just to be in the inner circle of the super wealthy, that has a value of its own, even just for people’s egos. There’s a guy I talked about in the book named Richard Watts, and he actually literally calls himself a consigliere for these very wealthy families. He’s a lawyer. No matter what you need done, he’ll get it done. It’s crazy stuff, like Crazy Rich Asians. He has clients, and their kids want to get married—their rich daughter wants to marry a middle class guy. And they’re like, who is this guy? Check them out, go check them out. So he’ll hire this private detective to go check out everything about this guy’s past. Does he have a baby mama somewhere? Is he lying about anything? Does he have any hidden criminal record? There’s not as much trust there, especially with the parents because your children are out there in the world.

And a lot of times, children of wealthy families feel like they’re under this umbrella—they’re smothered. They’re too close to the mothership. The money binds them tightly to it. It’s like a tractor beam. You get these very wealthy families, and usually, it’s the patriarch. So you got the patriarch, and for generations, the family stays close because they’re all trying to stay close to that money. That’s great for the patriarch because he can have the family reunions, everybody comes, and they toast him, but it can be stifling for young people. They can’t fully launch because they don’t want to be written out of the trust. If you watch Succession, they always talk about the trust. What’s the deal with the trust?

Robinson

I wanted to ask you more about the sociological piece of your book, understanding what it is like for these people and what these people are like. I assume that one of the questions you have probably had to answer about this book is that people want to know, from someone who knows, whether money can buy happiness. My takeaway from your book is not really, but it can help with a lot of things.

Mechanic

First of all, to be poor is to be miserable, and to be really poor is to be really miserable. It’s horrible. There are studies that are done on money and happiness, and I just actually wrote about for this for The Atlantic on how we put too much stake in these studies because actually, the effect is pretty small. But for people at very low incomes, there’s a direct linear relationship between the logarithm of the income and self-reported measures of happiness. And that makes sense because it’s really not happiness you’re measuring, it’s the lifting of misery at the lower levels. Because if you make $30,000 a year, you can barely pay your rent and housing—it just sucks up most of your income—you have to scrimp and save, and run up credit card bills. It’s an existence that is not fun.

As you go higher up, researchers have found a leveling off of that effect at fairly low amounts. Until fairly recently, a study came out that claimed it keeps going up well above $200,000, but then there are caveats in that paper. When the media reports of these things, they say money does buy happiness. But when you look at the fine print, it’s actually a really small effect, and there are all kinds of other effects.

For example, if you have children or if you’re a caregiver, your happiness goes down. And you think, but no, children bring you joy. They bring you joy, but they also bring you misery because you’re only as happy as your least happy child at any given time.

I just want to talk about children and wealth. Children who know they’re going to inherit a lot of wealth, especially through the family trusts, it’s never really yours—it’s sort of this mass of wealth floating around that you have to stay connected to. I think of Elizabeth—not her real name, but someone I talked to in the book—and she talked about her inheritor friends, including one was one of the Rothschild heirs and so forth. She said there’s a vagueness about these people, a sort of meandering through life. It’s like there’s a low stakes to things: you take a job, and if you don’t like it, just quit because you don’t need to be there. Money is such a motivating factor in the way we define ourselves.

It’s not so much that I need money to think well of myself. It’s more that we measure success by money, which is a bad thing to do, by the way. But if money is not a motivating factor, then what is your motivating factor? And society also perceives money as a measure of success. So let’s say I don’t need money, but I am doing a career that has very low pay while still not getting the respect. Our relationship with money is really complicated, and it can cause a lot of just strange pathologies.

Robinson

That very much comes through in the book. It’s just funny what you said about money as a motivator. Because I write a lot, I’ve published a lot. And people often say, how do you write so much? And I say, “if I don’t write, I don’t eat.” I write more because I have to be paid. If I don’t churn out constant writing for the magazine, subscriptions don’t come in and the magazine dies. It’s a fantastic motivator, and it’s made me a really good writer.

Mechanic

Write more, eat more, you get dessert.

Robinson

But if you’re guaranteed to eat no matter what, why should you write?

Mechanic

Right. And also, why should you do anything in particular? Honestly, my dad was a college professor, and my mom was a very early doctor. She was like one of the very few women in her graduating class in medical school, and she’d go into the doctor’s office to care for a patient, and they’d say, when’s the doctor going to come in? That kind of thing. And she was paid much less than the male doctors, and so forth.

Anyway, it was a comfortable, probably upper middle class childhood for me, and I went to a public university which didn’t cost very much even, but I didn’t have to pay for college. So even for me, there was a vagueness, but it’s not the vagueness like the person who stands to inherit millions and millions of dollars and knows it, and then just sort of dabbles. You look at people go into philosophy because they can. We’re seeing everybody wants to go into STEM because that’s where practical careers and money are, whereas the humanities are kind of shrinking because it’s seen as sort of the vanity things.

When I was going to school, you could do the humanities and then go into wherever—you had a good broad education. But now you got to go and make the money. It’s really that way in computer science. I was talking to Clive Thompson, who wrote a book called Coders. He was talking to a computer science professor, and he said, in the early days, the people who came into this field were just the geeks, the nerds—they just loved the code. Now, the kids come in to this field because they want the money. What used to be the mills to shuttle people towards Wall Street now shuttle to Silicon Valley.

Robinson

Probably not good for ingenuity, actually.

Mechanic

You go to Wall Street because there is only one reason to go, and that is to make a ton of money. That’s the only reason. It’s a soulless place. But in Silicon Valley, you can go and still make a lot of money and convince yourself that you’re making the world a better place. It’s the cliché.

Robinson

I was thinking, as I was reading your book, which of our stereotypes about the rich you had confirmed and which you challenge in the book. I think there’s a bit of both. I sometimes think when I’m reading your book, I think the “more money, more problems” thing becomes evident, and the idea that it’s probably not good for many people to have a lot of concentrated wealth. It’s not good for them or for anybody else.

Mechanic

If wealth just drops into your lap, the proverbial jackpot moment—in fact, part of the book was the idea that we have this fantasy in our society: we love the strike it rich thing. When I was a kid, I never cared that much about money, but I did love the idea of treasure and finding treasure. I used to go to the park behind my house and the old men with the metal detectors would walk around looking for stuff. I would follow them around. It’s like when you go up to a fisherman and say, what did you catch? It’s the same kind of thing. What did you find? Because the idea of finding something like a trove of gold doubloons or whatever, I love that. And I read Richie Rich—I went back and looked at it recently. It’s a weird comic. Anyway, that’s another story.

When we actually get the jackpot, it’s like, okay, now what? Because the fantasy is you’re going to be Thurston Howell III, and you will live in luxury and sit by the pool. Actually, I talked to the same woman in my book, Elizabeth, and she said, I know these guys made a friggin’ fortune in Silicon Valley, and then they retired at 45 and are spending their time golfing with 70-year-olds. And after a while, it’s like, this is just so boring. The hell am I doing? Another guy I talked to in the book who was a lawyer, his wife’s father died, and then both of his parents died, all in a very short period.

And all of a sudden, they had this ridiculous inheritance that they hadn’t expected. He thought, I don’t really like my job, I’m just going to not work anymore. And he could. So he started joining the boards of progressive nonprofit organizations and so forth, but he said, it was really uncomfortable because so much of us define ourselves by our work and what we do, and all of a sudden, I had all this money. I wake up in the morning, not knowing what I had to do today. And then he’d be places, and of course, the question is, what do you do? It’s hard to answer that question without telling them, actually, you don’t need any money because you inherited all this money. So, it’s really different, depending on how it comes. Inheriting a jackpot is a different thing than a jackpot that you scraped away for years and years and years: you worked to build a company over 30 years, sold it, and all of a sudden, you got $500 million. You have nothing to do, but you are incredibly rich. What then?

I wrote about in the book how I went to this charity poker tournament hosted by Tiger Woods in Vegas. Russell Westbrook and all these company founders were there, and they’re playing with a $10,000 buy in—it was all for Tiger’s foundation. I met this guy who is in his 30s, and he was with this cannabis company and sold it for a billion dollars. He was a super nice guy. He had this vape pen, but it was bespoke, it was bejeweled. Someone told me what it cost him: about 100 grand, and he had it specialty made. His fiancée was there. She was super nice, and was all like Gucci-ed out. I also heard he had just come back from London, where he had bought a hotel and didn’t even tell his wife about it. She was like, what?!

Robinson

Like you were buying a pastry.

Mechanic

Exactly. Do you want the croissant or the hotel? That’s the crazy thing, at these levels. I have a couple of friends who have sailboats, a 25 or 30 foot boat or whatever. And so, we went out on the San Francisco Bay last weekend, and it was really rough. It was actually kind of miserable, but at first was really cool. It’s great to have a friend with the boat, but I don’t own one because it’s a huge hassle. And then if you own it, and you don’t go out all the time, you feel like it’s just this albatross. Then you got these guys who are buying yachts bigger than a football field, literally 400 meters or whatever. Jeff Bezos’s yacht apparently has another yacht just to service it, just to bring it stuff. It’s like the side yacht.

And how often do you think he’s on that? A couple of weeks a year. I also wonder how much of it could be written off as a business expense because it’s used for entertaining clients and business partners. We’re probably subsidizing that lifestyle, not to mention when we order stuff on Amazon Prime.

Robinson

When Bezos went to space, he said, “thank you to our customers and to our employees because you made this.”

Mechanic

They literally made that, but until recently, they weren’t even paid minimum wage. Well, they were paid 15 bucks an hour until just a couple of years ago.

Robinson

“This was made possible with the money I didn’t pay you.”

Mechanic

Here’s what I don’t understand. So, in Washington, there was a state ballot proposal to raise taxes on the super wealthy to help fund middle class initiatives. And Bezos and Steve Ballmer from Microsoft, they spent hundreds of thousands of dollars of their own cash to shoot down this thing. I just think, why? What is this to you, pal? You have more money than could be spent in 20 lifetimes, and you’re going out here and spending money to shoot down this thing that’s going to tax you more. Come on.

Robinson

It will make zero difference to your lifestyle.

Mechanic

Zero. You could cut their money well in half or by a quarter, and it would still make probably zero difference. So that gets us to the Bill Gates giving pledge. People say, but the wealthy do such great things with their charitable initiatives. Not if you look at the stats. Firstly, the pledge is to give away half of your wealth. It used to be during your lifetime, but they scrapped that. So they say a majority of your wealth, which is half plus a penny. That’s the majority. And it’s not binding. You sign up for this, you can get all the acclaim and just not do it.

Robinson

They all seem to be still pretty rich.

Mechanic

That’s the thing. One guy I talked to had written a book on philanthropy, and told me that the people currently on the list, except for one or two, are all richer than when they signed the pledge. How are you giving away half your wealth, and you’re richer now than 20 years ago? Very few people are giving their money away at a sizable enough clip.

Now, MacKenzie Scott is a good a shining example of how to do it. She’s just shoveling it out as fast as she can. Instead of creating some foundation and in perpetuity, she is just got a bunch of smart people around to help her vet whom to get this money to make a more equitable future for the rest, and then also figure out how much money they can handle. Because you can’t just dump $100 million on a small nonprofit. It’ll destroy them just as it would destroy a person.

Robinson

Sure. I’ll believe the giving pledge when one of them is actually poor. And you mentioned in the book this diminishing utility thing that’s really important. For example, if I give you a burrito, that’s very nice. If I give you a second burrito, that’s less enjoyable than the first burrito, and then your 47th burrito is just totally unnecessary.

Mechanic

Oh, and I will hate you.

Robinson

They’re willing to give out wealth, but they never give up any utility. Because their lifestyles never ever change.

Mechanic

Right. And for a lot of them, philanthropy is a strategy. It’s part of a whole mix of things like reputation and burnishing tax breaks. How can we give away the right amount of money so it will make us look good, but we don’t really have to give up anything substantial? In Silicon Valley, the big thing is the donor advised funds. It’s like a tiny foundation that is just like a parking place for charitable money, which you put in this account when it’s convenient for you.

When you need to take a big tax break, you put a chunk in this account, and the federal government has no requirements that you have to pay it out at any particular time. Foundations right now only have to pay out 5% of their total assets per year, and that includes overhead. Overhead would include sending your board of directors to Ibiza for a week-long board meeting at a fancy hotel.

So, you could have a foundation that is accumulating money because it’s all invested anyway. It’s just piling on more and more money, and you can keep expanding it and buying new buildings for it. And you could have members of your own family working there at pretty high salaries. What wealthy people get away with are just legion. I know some of them are totally on the up and up and this is a charitable foundation, we want to do good, we’re going to spend it down in 50 years, and that’s great. Congress really blew it when it came to setting up the rules around foundations. As I talked about in the book, John D. Rockefeller first went to Congress trying to get a charter for the first general purpose charitable foundation. Congress was like, forget you, dude. This is back when there was a lot more hostility towards these super wealthy people. Teddy Roosevelt was ripping on him, and people testified that this was just incredibly undemocratic. And it is undemocratic.

So if, let’s say, your marginal top tax rate is 37% on your income, and you give away $100 million, that means 37% of that 100 million is covered by the US taxpayers. If you’re not spending that money on things in the public interest, basically you’re just having taxpayers subsidize whatever your priorities are. And that is another form of flexing power. It’s the opposite of democratic. People will say that the government is a lousy charity and it’s inefficient. That’s true. But the government is not a charity. That’s not its role and not what it is supposed to be doing, and there’s no doubt there are things that private interests can do better and more efficiently, but they can do that without government help.

Robinson

I read the Wall Street Journal‘s “Mansion” section every Friday, and I’m continuously appalled by excess upon excess. There was a feature in the Times the other day about the increasing cost of high-end toddler birthday parties that can run $75,000 or more now, and they’re getting increasingly complicated. You saw a lot of the really absurd and of how wealth is deployed by people who don’t even know how to spend their money. Could you give us a little insight into the mindset of someone who has spent $75,000 on a child’s birthday party?

Mechanic

The mindset is that it’s play money and is meaningless to you. That $75,000 could do a wealth of good for some poor families. But instead, we’ll just throw it away here. I think there’s this attitude of “I earned this, and I can use it however I want,” and if it’s frivolous, it’s frivolous. Screw you if you’re going to criticize me because I can do it. You can get whatever you want.

There was a part where I was talking about the Centurion Card, the Black Card, and someone who had one. It’s an American Express card that’s only given by invitation to very wealthy people, or people who spent at least $350,000 a year or something on their credit card. They wanted the actual horse that Kevin Costner rode in Dances with Wolves. And so, they asked the concierge to find it for them. So the Black Card concierge goes and tracks down the horse in Mexico, buys it and delivers it to the guy. Another Black Card holder wanted some sand from the Dead Sea for his child to use in a school project in London. And so, they sent a courier to the Dead Sea, got some actual sand, and had it shipped to London.

These things are just silly. They’re silly, and they’re excessive, but they’re also just a slap in the face of people to people who are hurting and struggling. That’s the other side of it. You can say, this is harmless, it’s their money. But to watch people almost literally burn their money for stupid things and things that people would ridicule them for. Kim Kardashian, in the middle of the pandemic, was Instagramming about how she took all these friends of hers to this island for this getaway so they could pretend things were normal. She’s bragging about this, and everybody else is locked in their houses, out of work and out of school, and people are really suffering. That’s the bubble. That’s pretty distasteful. I would think, even in the bubble, it’s distasteful. It was a clueless move.

Robinson

And you think about what all that wealth could do if deployed to different ends. Many lives could be better.

Mechanic

It could be. But, you could also just tax these people more because they’re clearly not spending their money for you.

Robinson

I did come away reaffirmed in my conviction that they should be taxed more.

Mechanic

People say the government sucks and they build nuclear weapons. They do all this. The government does many questionable things, and it’s incredibly inefficient. But there’s also an argument that people should be taxed more, just because. Not so the government has more money, but to rein in some of the wealth inequality because it’s really damaging to society. It gets rid of the middle class, and if you lose your middle class, you lose a lot of the stability in society. You look at these really unstable countries, and they have extreme wealth inequality, and we’re becoming that way. Look at how unstable our society has become. We’re teetering on the brink of democracy imploding.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.