How the US Fueled the Spread of Islamophobia Around the World

Khaled Beydoun explains how Islamophobia in many parts of the world was worsened by the U.S. “war on terror.”

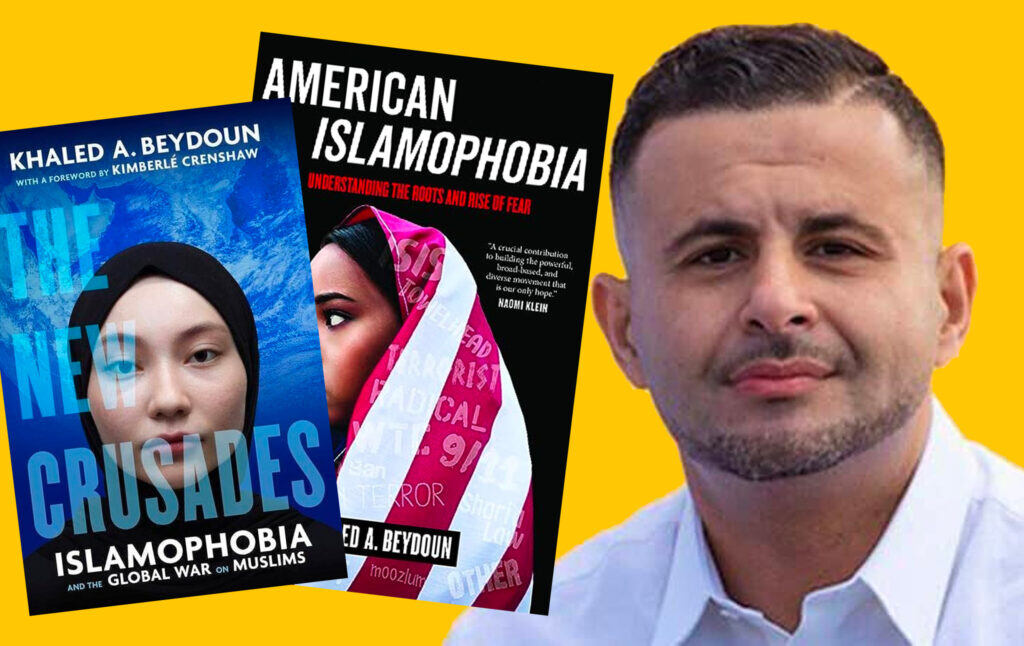

Khaled Beydoun is a professor of law at Wayne State and the author of two books, American Islamophobia: Understanding the Roots and Rise of Fear and The New Crusades: Islamophobia and the Global War on Muslims. American Islamophobia is a definitive analysis of the roots and spread of anti-Muslim animus in the United States, but The New Crusades expands the analysis to look at how the same bigotry manifests around the world, from France to India to China to New Zealand. The new book also shows how the “Global War on Terror” launched by the U.S. after 9/11 helped to fuel anti-Muslim bigotry elsewhere—for instance, China’s persecution of Uyghurs deploys justifications and rhetoric lifted straight from the Bush administration. He joined Current Affairs editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson on the Current Affairs podcast to discuss the books.

Nathan J. Robinson

I was thinking about where we could begin, and it strikes me that your new book is an extension of what you wrote about in your first book. Your first book focused on the United States; your second book expands to a global focus. But both books have, at their core, the American global War on Terror that began after September 11, which I know was formative for you. So I think a logical place to begin the conversation might be to take us back a little bit to what happened after September 11, 2001, with the climate and the experiences of American Muslims then. Because one of the things that you do so well in these books is take us beneath media narratives to focus on the people whose lives are actually affected by the things that states do in the name of combating terrorism and “radicalization.” We could start with the beginning of this thing called the “global War on Terror,” the reverberations of which are the subject of both books.

I want to go through the global Islamophobia that you discuss in the new book, but let’s stay for a moment on the United States. Perhaps you could tell us a bit about the environment after 9/11 for American Muslims. This was your kind of coming of age. I sort of remember this. I was in seventh grade at the time. You definitely remember this, but we live in the United States of Amnesia, and we forget the explosion of bigotry, hostility, nationalism, and militarism that happened instantaneously. It didn’t begin then, as you point out. You discuss in American Islamophobia the long roots of Islamophobia in America, but it was a terrifying moment I imagine for every American Muslim.

Khaled Beydoun

Yes, I think that’s a good sort of summation of the thread between the two books, as you had this formative transformative moment, the 9/11 terror attacks, which gave rise to the War on Terror. And again, it was a global War on Terror. It wasn’t intended to be confined to American boundaries and the American experience, which was the focus of the first book. But when writing the first book, and then talking to people about the book and touring, I realized that I was basically doing a disservice to the broader enterprise of this new global War on Terror by not fully addressing what was taking place in places beyond the United States in Europe, the Middle East, South Asia, East Asia, and so forth. When speaking to people who had experienced the War on Terror in dramatically different ways, being somebody who was very keen on using my academic platform to be a public commentator on these issues, I wanted to give voice and amplify the experiences of people in places like India, China, France, and Sweden, and that’s the spirit of this new book.

I was a young man making my way through school at that point. And, in a matter of a day’s time, the entire feel, and sort of tenor, of the country had changed dramatically in the direction of demonizing people who looked like me and believed like me as the new enemy, the primary enemy. When you saw that being manifested in the rise of hate crimes and incidents, our mosque was vandalized in our community. Muslim women who wear the hijab were being attacked and accosted by hatemongers very prolifically. The best way to characterize it is this was a moment of not only state-sponsored response to what had taken place in New York and Washington with the terror attacks, but this was societal vengeance where people—lay people on the ground, Average Joes and Janes—were identifying and attacking anybody who looked Muslim or what they imagined Muslims would look like. So, it was this new moment where people like me became the new political and geopolitical enemy of the United States, the strongest country in the world. It was very frightening and unsettling, especially being a Muslim American myself. How do you reconcile these two identities, which after 9/11 were set to be at civilizational odds and war?

Robinson

As I said previously, this has long roots. The United States had its Muslim boogeymen Saddam Hussein and the Ayatollah beforehand. Of course, Edward Said had written Orientalism long before, about the way that the kind of clash of civilization lens was present throughout Western media, but it was on steroids after 9/11, where Samuel Huntington went from being rejected for being a little bit fringe to the dominant analysis of the way the world looked.

Beydoun

Definitely true. The neoconservative government which presided over the Bush administration had catapulted the likes of Samuel Huntington and Bernard Lewis. The best way to think about them is these are Neo-Orientalists who believe that the West is sort of this monolithic, aligned, geographic/civilizational entity, and as a consequence of 9/11—even before 9/11, like you’ve stated— was on this predictable path towards perpetual war with the Muslim world. 9/11 legitimized that for the government. And it catapulted the likes of Samuel Huntington to be the mouthpieces of the day. But you’re right: I think there were always Muslim boogeymen before 9/11. You mentioned some of them: Muammar Gaddafi of Libya; Ayatollah Khomeini with the Iran hostage crisis, which really penetrated the American imagination in 1979; Saddam Hussein throughout the 1980s and 1990s. But at that juncture, these were secondary villains in the American sort of geopolitical Rolodex. The Soviet Union was always the primary villain, and when the Soviet Union declined, there was a vacuum, a void, and 9/11 had elevated this motley crew of Muslim villains. The primary villains were Al-Qaeda and the Taliban, these transnational terror networks, which committed the 9/11 terror attacks and the range of other terror attacks that took place during that time. They occupied public enemy number one after the Soviet Union created that void, and the 9/11 terror attacks opened the door for this full-scale crusade against Muslims and Islam on a global level.

Robinson

It’s shocking, in retrospect, almost to realize the size of the gap between the number of people who perpetrated 9/11 and the number of people upon whom vengeance for 9/11 was exacted. Even the Taliban were not responsible for 9/11. It was a tiny group of people. And then the Bush administration’s rhetoric, the global War on Terror, expanded to country after country. I think Brown University’s Cost of War Project estimated the number of refugees and people killed as a result of the post-9/11 wars, and it’s millions upon millions.

Beydoun

Yes, what’s really troubling about the response with the War on Terror is that it conflated an entire faith group or an entire global population of 1.7 billion people with the very horrific and atrocious act of a handful of people. Even when you look at the demographic origins of the culprits of the 9/11 terror attacks, these were generally Saudi men. They originated from Saudi Arabia and adhered to this very fringe, overzealous iteration of Sunni Islam called Wahhabism, that, again, has roots in Saudi Arabia, but none of that was identified really closely by the Bush administration because that careful narrow framing of whom the terrorists were would have disrupted the economic and political alliance of the United States with Saudi Arabia. So, they didn’t want to do that, obviously, because we have exclusive rights to oil in that nation. And like you said, there was no direct sort of nexus between Al-Qaeda and the Taliban. The Taliban were a ragtag political movement in Afghanistan who might have given safe haven to Al-Qaeda terrorists—I think that was the link. But the Bush administration swiftly commenced war in Afghanistan in the days after, but it didn’t matter. These sorts of careful, meticulous connections didn’t matter in the imagination of the American government, and definitely not the people because they just wanted some sort of vengeance. I think what is distinct about American culture and American society at large is that it has a hyper violent trajectory, and a lot of that is rooted in American history where mobilizing the thirst for violence on the part of the American people is not hard to do, especially in the wake of massive tragedy like the 9/11 terror attacks. And one quick note to make mention of is, it’s important to think about the global War on Terror as a politically and economically expeditious instrument that the US government used to expand its interests, not only in the Middle East, but globally. So, it was an imperial and rational tool that enabled the expansion of the American Empire.

Robinson

It’s so interesting, and so important, what do you say about the American capacity for violence in that way. It made me think of the response to Pearl Harbor, actually, which was very similar towards Japanese people. When you go back and look at the US propaganda after Pearl Harbor about exterminating all the Japanese and that there are no civilians in Japan—where the massive fire bombings of Japanese cities happened because it was assumed all Japanese people perpetrated Pearl Harbor—that same kind of thirst for vengeance after being attacked results in the conflation of many different people, who are entirely different from one another, into one group upon whom it’s legitimate to punish for the act of a small few.

Beydoun

Definitely. If you look at the mass internment of Japanese, the majority of them Japanese citizens—120,000, I believe it was, Japanese residents of the West Coast—were rounded up and placed in internment camps in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attacks in 1941. The parallels there are so stark, that race and religion can both be used to easily other a people, demonize them, and then justify very strident and Draconian policies that blame an entire group only by the way they look and how they believe, even though there’s no direct connection. In the Japanese case, they were thought to be spies engaged in subversive treasonous activity, passing intelligence back to the Japanese Empire. There was no evidence of that, but they still sort of justified the mass internment of the people. A similar thing took place in the post-9/11 context, with this new architecture of policies that are being put in place to police Muslims, not only here in the States, but globally.

Robinson

I think the United States definitely hasn’t reckoned with the amount of destruction that was wrought in the wars that we waged post-9/11. I mentioned some of the tallying of the number of refugees that have been generated that has been done recently, the utter wrecking of Afghanistan and Iraq, and not just starting there. It’s just an extraordinary level of brutality that this country is directly responsible for.

Beydoun

Yes, brutal in a range of ways. I think that the Iraq war is even more nefarious and illegal than the war in Afghanistan. The number of killed in Iraq is anywhere from half a million to a million of innocent civilians in a war that had no justifiable legal basis. But it was also brutal on the American end. In this new book, I speak to a gentleman who lives 10 miles away from me in a largely white working class community, who, because of no other economic options at that time, chose to enlist in the Iraq War, and it really destroyed him. I met with this guy, sat with him for coffee. He suffered from a range of diseases and mental health issues. It destroyed his family life. He came back and is essentially jobless now and has no one tending to him. So, it was brutal on a range of levels. It was brutal to the people who were targeted as prospective terrorists in places like Iraq, but it deployed masses and masses of young American men to fight and essentially sacrifice their lives and futures for a war that was entirely baseless, unjustifiable, and illegal.

Robinson

Coming back to what you say about this capacity for violence, you have this quote from him where he’s describing why he joined up. He said, basically, the only thing he knew was that we had been attacked, and he wanted to defend us. It makes you understand that if that is the limit of the information that someone is given, someone from perfectly decent motives can end up being enlisted to take part in just horrific atrocities. Of course, the same thing that is being told to Russian soldiers now in their illegal war is they have to defend the homeland. And so, all these terrible things can be done by people who are just given this very small amount of information: this group of people did this thing to us, now we have to go and defend ourselves.

Beydoun

Yes, it’s really frightening how very good men, like the man I spoke to in the book, can be made into monsters with a scintilla of propaganda. When I sat across this guy, he and I could be friends. We liked the same things. We live 10 miles away from one another. He was sort of an alpha male, and I say that in a benign way, where his objective was to just take care of his family and his community, and he had a love for his country. Those are beautiful things to be commended. But the way in which the media was disseminating this violent, vile information about Muslims—people like me, somebody who sat across him at the table—mobilized him to want to enlist in a war in a place that he had no knowledge of. He just knew that he wanted to defend his country and wanted vengeance, and that these Muslims, these Arabs, who were a world away, were the culprits of the 9/11 terror attacks. So, he was ready to volunteer his body. This guy didn’t go to college—he’s not an educated guy—and when he came back from the war, he had nothing to come back to. When I met with him, you could tell that he felt deceived by this country because the tone of his allegiance to the country had changed dramatically. He was skeptical and suspicious, and he didn’t have the same love for country that he did before he left for that war because he realized how the war had broken people like him, and how it told lies about people like me. He’s grown to be someone I call a friend and somebody that I still speak to today.

Robinson

What’s interesting, listening to what you say there, is that you could be quoting directly from someone I interviewed a couple of months ago who was a Vietnam veteran, who described almost the same experience. He grew up in the 1950s on American World War II films where we were the heroes, and signed up to join the Marines in high school and went to Vietnam. He found himself killing Vietnamese peasants, supposedly to stop communism, and came back just thinking this country had lied—a totally broken person. This is a very common experience of these myths, this other-ization process that can just shatter someone upon realizing that human beings are on the other side of this.

Beydoun

Yes, I think it was Albert Camus [Editor’s Note 10/3/23: It was Jean-Paul Sartre] who once wrote that it’s rich men who send poor men to fight their wars, and you see this with the Vietnam War and contemporary wars like in Afghanistan and Iraq, where these are poor people on either side killing each other to advance the interests of wealthy men who would never dare to expose themselves, or their sons or their loved ones, to the specter of war.

Robinson

You mentioned earlier there are media messages that a guy like John, that veteran you talked to, would be fed, and I think one thing that would be good to discuss is the way in which Islamophobia and Orientalism is implicit in Hollywood and the press, from American Sniper to Call of Duty. The assassination of the Iranian general, Qasem Soleimani, was reenacted in the latest Call of Duty game. It’s all through various pieces of American media.

Beydoun

Definitely. So when you meet somebody like John or when I go to college campuses, and I meet young, white, non-Muslim men and women who adhere so strongly to Islamophobic views. I can’t blame them. It’s a natural sort of perspective for them to have because every channel and medium of importance in the United States, whether it be television or Hollywood, whether it be conservative, centrist, and even sometimes liberal news, is peddling this image that any mention of Muslim identity is somehow connected to this specter of terrorism. Terrorism and Muslim identity in the contemporary political, popular, and entertainment parlance are virtually synonymous. Whether you’re watching Fox News, or Homeland on Showtime. So you can’t blame young people for making that correlation. You can’t blame any well-intentioned individual who doesn’t have direct access to Muslim communities, or knows anything about the Islamic religion or the broader Middle East region, for believing that these Muslim folks are inclined toward terrorism. I’m not somebody who approaches individuals who have negative or even malicious views of my faith as evil, wrongdoing, flat-headed people. Because part of being American in the last 20 years since this War on Terror has been launched, is to be Islamophobic, in the same way that being American in Jim Crow America, when segregation was the law of the land, was to be anti-Black. More than just culture and policy, I think it’s even deeper than that. These sorts of definitive arrows or moments recreate what it means to be American. It’s baked into the very existential matter of what identity means, because of media, culture, and law. I talk about this dialectic of Islamophobia in my work, and how that reshapes American identity in the mirror opposite direction of this reconstructed Muslim villain who was the very opposite of who we want to be and who we are as American people.

Robinson

I see. So that opposition is central, you’re saying, to our self definition?

Beydoun

Very much. Yes. Another way to look at it is like how Edward Said frames and theorizes Orientalism, that the identity and sort of character of the West or the Occident is shaped and curated in opposition to how we reshape the Orient. And that’s also true for American Orientalism or American identity regarding Islamophobia.

Robinson

So the definition of the West includes the West is not them. And as Americans, we’re defined by not being other people.

Beydoun

Yes. You may remember the anti-Sharia movement. There were laws being enacted, in states across the country a couple of years back before these anti-critical race theory bans, where states were looking to ban Islamic law. The very language of this legislation, which would say exactly what you just said. “We’re not them.” “Our values are different.” “They’re trying to take us over.” There’s a civilizational binary that now is being echoed across Europe, in places like Sweden with the rise of the Sweden Democrats, in France, which has long been a hotbed of Islamophobia in that continent, and in Germany and the UK to an extent. You see this dialectic being replicated in countries across the world.

Robinson

This is what I want to get to because this is the core of your new book. In the United States, we might think that some of the worst and explicit post-9/11 Islamophobia has been dialed down a little bit in the mainstream press, as we have found some new villains of the day in the form of China, Russia, critical race theory, transgender people, and whatever it is. You say that essentially the US War on Terror planted this seed of Islamophobia that has now spread across the world, from China’s prosecution of the Uyghurs, to India, to France. So, perhaps you could talk about how the US global War on Terror has now contributed to this massive global problem?

Beydoun

Obviously, we all know that the United States is the primary global superpower and the American War on Terror was meant to be a global crusade where then-President Bush used that word “crusade” and specifically posed to nations across the world “you’re either with us or against us”, leveraging American might against smaller countries who want to align with the United States for a range of economic and political reasons. So, there was this sort of flexing of American might to force countries across the world to flank alongside the United States in this search of these Muslim boogeymen in their midst. As a consequence of that sort of geopolitical framing, the global War on Terror provided countries across the world with a new language for how to frame and profile their Muslim populations—new policies and programming, an entire sort of lexicon and architecture to police, persecute, and punish Muslim populations. So, you saw as a consequence of this direct ultimatum and this new sort of language and policing framework in countries across the world. China, for example, which had always had issue with its Uighur Muslim population—essentially a struggle over land before 9/11—was profiling and characterizing the Uighur Muslims as this sort of savage and unruly band of subversive criminals who would not bend or capitulate to the broader Han supremacist Chinese communist project. After 9/11, and after Bush visited China in October, you see in acute marked shift of the regime doing away with that language in fully adopting the American language of counterterrorism and counter-radicalization. “The Uighur Muslims have a direct link with ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and these transnational terror networks”, which enabled and provided them with carte blanche to persecute and crack down on these Uighur Muslim populations in ways that were unprecedented, and in ways that aligned with the greatest superpower in the world that was democratic in nature. So you could do what you want to do but escalate it under the auspices of the War on Terror. The same thing happened in India: a Hindu supremacist government came into being in 2014, staunchly anti-Muslim, and adopted an American style lexicon and strategy towards persecuting Muslims. The same thing, sadly, happened in some Middle Eastern countries, where Muslim organizations are being framed as terrorists across Europe. So, in summary of the American War on Terror, it basically extended almost carte blanche to governments to crack down on their Muslim populations in ways that were unimaginable before, and that were extended by a country that is globally regarded as being not only the world’s most important democracy, but the protector of civil liberties and civil rights.

Robinson

There’s all this opportunistic and hypocritical American outrage about China’s hideous prosecution of the Uyghurs. And then, as you say, when you read the Chinese government’s justifications, they sound like the Bush administration. It’s incredible. They say, we’re undergoing deradicalization projects because of the serious threat of radical fundamentalist Islamic terrorism.

Beydoun

Very much so. There was a program coming out of China in 2016, called Destroy All Terrorism in the Xinjiang Region, something very nefarious like that. And once you read the fine print of the policy, it sounds a lot like the counter-radicalization policy being used by the Obama administration. Even before that, Prevent, which was a similar policing program used in the UK, the language—the framing of prospective terror threat, the process in which somebody Muslim becomes a radical—is almost adopted wholesale by the Chinese government from American and British origins.

Robinson

You mentioned Obama there, and I think one of the important points is that the United States government policies are not just pernicious under our overtly Islamophobic presidents.

Beydoun

One thing I try and do with my work is to demystify this idea that Islamophobia is only a culture, perspective, or legal system coming from conservative or right-wing elements. It might be more explicit when it’s coming from the Republican Party, but Democrats and liberals have been just as wed to Islamophobic currents and attitudes as the right has been. President Obama spearheaded and implemented this counter-radicalization program which had a destructive impact on Muslim communities like the one I live in here in Detroit, and in places like Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Boston, that pierced into the heart of Muslim geographies in ways that were even more destructive than FISA surveillance and the Patriot Act—programs being implemented by Republican leadership. And in my opinion, I think counter-radicalization still stands as the most pernicious structural Islamophobic program ever instituted by an American president, and it was brought forward by President Obama, who was widely regarded as being one of our more progressive presidents. So that tells you a lot about how Islamophobia, from a systemic standpoint, can very much be ushered in and amplified by progressives or liberals.

Robinson

Can you say more about this? Because I think when people hear counter radicalization, some of them who have not been on the receiving end of it might think, but what’s wrong with that? Surely, radicalization is the one thing that we want to prevent.

Beydoun

Yes, of all sorts. But I’ll break it down. Radicalization is only a concern that is made synonymous with Muslim sort of practices. It has a direct effect of eroding core constitutional rights, like the free exercise of religion and free speech. So, I’ll give you an example. I’m a law professor. If I start growing a beard or going to a specific mosque, or fasting on Ramadan, stuff that is entirely protected by the First Amendment—I have the right to freely exercise my religion as I see fit without governmental encroachment. However, these behaviors that I just mentioned, that are protected by the First Amendment, from a counter-radicalization standpoint, would be viewed by the FBI in their local informants as activities that might give rise to me becoming a terrorist— entirely benign, innocuous religious activity. In addition, let’s say somebody like me, who is critical of the War on Terror, puts up a tweet or a post saying I think that the war in Iraq is entirely illegal or unjust, or that the Swedish government looking to shut down mosques in the center of Stockholm or the French policy of banning the headscarf is an entirely racist and xenophobic measure. That kind of free speech, which is protected by the First Amendment, might be read by an FBI officer or informant as a symptom of me radicalizing. So, that’s the danger of counter-radicalization policies that’s essentially punishing activity that is entirely protected by the First Amendment and other constitutional safeguards.

Robinson

And you say it is structurally Islamophobic, in part, because it is associating one’s level of devotion to one’s religious faith with radical Islam. The more serious and committed a follower of Islam you are, the more you are suspected as a “radical”.

Beydoun

Of course, that’s exactly it. It has a direct correlation with piety. So, the more pious and more outwardly expressive with their faith one is, the more inclined the FBI and their proxies are to police them.

Robinson

I think it’s worth mentioning that even in countries that pride themselves on their liberalism and tolerance, you find the same kinds of risks of Islamophobic violence. You talk about New Zealand, a country that I would classify as priding itself on its tolerance, and, of course, that’s a site of one of the most hideous acts of Islamophobic violence in recent history.

Beydoun

Yes. I think that in largely liberal democratic states, like New Zealand, Sweden, Australia, and France, you have very concerning strains of Islamophobia that rise from these vacillating movements of populism, where politicians or pundits in these places use Islamophobia as a strategy to galvanize and mobilize followers, and to justify things like economic decline, rise in immigration, declines in the population of whites living in that country, “white anxiety”, things of that nature, to spur this frightening rise of vigilante violence. I think what happened in New Zealand is a very stark example of that, with what was happening in Australia. The killer came from Australia, which has really concerning currents of anti-Arab and anti-Muslim politicking and white supremacist factions that rise from that. That really motivated this guy to hop on a flight and kill about 50 people in two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand. And lesser things have taken place in recent time. In places like Sweden, I think it was two weeks ago, this staunch and ardent Islamophobe Rasmus Paludan from Denmark, engages in similar violent Islamophobic theater by burning Qur’ans in public squares. That kind of activity has been encouraged, and in some respects incentivized, by the rise of Islamophobic populist like the Sweden Democrats in that country. It’s critical to understand that there are liberal democratic roots that can give rise to concerning fronts of Islamophobia because they open the door for populists to become very politically influential, and potentially overtake political power. That’s the story of Donald Trump here in the United States, too.

Robinson

And the level of dehumanization can reach just such terrifying extremes. The Christchurch shooter livestreamed it like he was playing a video game, just not viewing people as people at all. And we might say, that man is such a hideous sociopath, such an extremist. But then truly when you look at United States formal policy, with the use of drone strikes on weddings, you could look at the Christchurch massacre and say, how could someone kill people like they were ants or like they were video game characters? But, the Obama administration’s actions in the War on Terror, when you look at some of the drone strikes that were carried out, I would say are morally are an inch away, or not even that.

Beydoun

You said something earlier which was really prescient and lined in with the conversation we’re having now. Younger generations are being socialized to engage in a form of impersonal violence that has become really concerning. With video game culture, for instance, all these young people play these video games like Call of Duty, where the villains are Muslim and non-white. Killing is baked into their daily existence by playing these video games, watching these movies, and interacting with social media where they’re interacting not with real people, but with avatars that they can freely curse out and threaten in a very non-intimate way. The conventions of war today sort of follow that same construct, where you’re not seeing your rival anymore. There’s no boots on the ground anymore. You’re pushing a button or launching a drone a world away that’s destroying entire villages or bombing weddings. So it’s only logical that this a natural progression birthing a new age of killers who engage in that very same activity of not viewing their targets as fully formed human beings, but as non-beings that can easily be killed and mowed down en masse because that’s how we’ve been socialized to behave. It’s easier to do so when the people don’t look like you. And it’s not only a Muslim problem. You might recall this mass shooting in Buffalo, where a young white man drives up to a largely Black grocery store and does the same thing as the killer in New Zealand. He livestreams and kills tons of Black folks in similar fashion.

Robinson

Also, with the El Paso killer, who said there was a Latino invasion of Texas. One thing you talked about in your conclusion is the standards of the varying levels of humanity that are applied to different people. You discuss the war in Ukraine, and obviously, you’re very upfront about the fact that the war in Ukraine is an illegal act of aggression. It’s a hideous atrocity. But you draw our attention to the fact that Ukrainian victims are viewed differently. They are given in the US press and by the US government an elevated status.

Beydoun

Definitely. I appreciate you prefacing the fact that I view the war as being illegal because I get a lot of slack for drawing these comparisons. It’s not a comparison to slight or critique Ukrainian struggle or people in any way. It’s just a meta narrative that highlights the double standards drawn along lines of race and religion where the American public at large, and American news outlets of importance, in the newspapers of record, elevate the human value of the Ukrainian people and Ukrainian victimhood far beyond the kind of attention and value that’s attributed to individuals in places like Palestine, Kashmir, or Yemen, and now the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria, which aren’t a war, but a human crisis nonetheless, in ways not entirely drawn to race—I think whiteness has a big part to do with the story. Some of it is American interests in Ukraine, obviously, and the alignment of NATO, but race and religion have a big part to do with it. And I think even the psychological affinity that we know most Americans see when they see a Ukrainian war victim or displaced individual: they look like them and their children. They’re able to physically map that person in ways that are far more intimate than somebody who was classified as a villain and as the other. And that’s why you see Ukrainian flags being waved on the homes of Americans and in ways that Palestinians, Iraqis, or Kashmiris can only hope or dream could be the case for them.

Robinson

Early in the war, there were some loose-lipped anchors in the news media who would say things like this is happening in a European city where you just don’t expect it—this implicit assumption that some populations almost make natural refugees, or it’s like their destiny to have their cities destroyed. Like that’s a normal or natural thing that they should be used to. This was true in Vietnam too, where there was this idea that Asian people don’t mourn their children in the same way, like life is cheap. There were all these myths that they’re not affected the same way that we are by the loss of life.

Beydoun

I didn’t know that. I didn’t know that was said about Vietnamese people. Oh, wow.

Robinson

There was, again, the idea that in East Asia, life is cheap. “They have a Buddhist tradition”—all this stupid stuff about how when their children die, it’s not as bad as when our children die.

Beydoun

I think the Ukrainian issue is very complicated for me because drawing these comparisons might render the message that I’m devaluing their struggle or devaluing the experiences of Ukrainian refugees scattered across Europe and the world at large. But the policy even reflects that. There was a recent policy out of Germany, and I think Denmark, if I’m not mistaken, where they were absorbing new Ukrainian refugees and simultaneously looking to send home Afghan refugees. And I think there were even some politicians—they might have been right-wing politicians—who echoed that same idea that we should absorb Ukrainian refugees because they’re of the same civilization as us. It’s implied in the media, but also explicated in the political discourse.

Robinson

We have a vastly greater moral responsibility to absorb Afghan refugees in the United States because we’re part of the reason that the country is starving to death. Maybe take care of the victims of your own crimes first.

Beydoun

I think that’s a responsible way to look at the way you go about your refugee and immigration policy. If your policies have been destructive to a nation and created refugees, then that might create a greater priority or responsibility on your behalf to attend to the refugee crisis that you’ve created. We didn’t go to war with Ukraine, so you could make a distinct case for absorbing Ukrainian refugees.

Robinson

I want to conclude here with the way that you counter the dehumanization that you document by telling people’s stories and going around the world and humanizing people, forcing us to look directly at and hear about the lives of those who are left out of mainstream account. Could you tell us whose stories you would like to be told and are telling in this book?

Beydoun

I think for me, that’s the greatest thread or dimension of this book. It’s a memorialization of stories that would otherwise not be heard if a book like this didn’t exist. It’s humbling to have the reach or platform that I have to be able to give voice to Uighur Muslim refugees living in Turkey, Syrian refugees living in the United States, displaced Rohingya mothers who have lost their children, and working class and indigent French Algerians living in the ghettos of Paris. Not only telling their individual stories of struggle against Islamophobic policy, but entwining all of these distinct narratives into a cogent tapestry that provides a real portrait of what global Islamophobia looks like. And it’s not all bleak, it’s not all negative. One thing I hope people who read the book walk away with is the idea that these are real stories about resilience, about people who have really clenched on to their spirituality and the strength they draw from it in ways to endure after experiencing considerable tragedy. One story that really stuck with me that I’ll share is the woman on the cover of the book. She’s 17 years old, and her name is Muslimah. She’s a young Uighur Muslim girl living in Istanbul, and she lost her father. She’s not sure if her father was killed or still locked away in a concentration camp. Just hearing stories like that, especially from young people trying to make sense of their lives, far away from home and from loved ones, for me entrenches this obligation to tell their stories in ways that I’m best able to.

Robinson

You have this great epigraph at the beginning that says, “This book is about people, not myths.” I like the way that sums it up because once you’ve destroyed the myths at the foundation of Islamophobia, you start to see the actual people in their full humanity. You say there that it’s not entirely a pessimistic or negative book. I think that’s very true. Because once you can let go of the simplistic fear-based worldview of Islamophobia, and you start to see people in all of their diversity and richness. Once those spectacles of ideology are taken off and you see the human beings, the world becomes a much better and less terrifying place. You’re not afraid of terror all the time. You get to be friends with your neighbor and make the world better. We could get along a little more.

Beydoun

Yes, definitely. And I think that another sort of objective of mine was to sort of do away with this idea that Muslims are all the Arabs and Middle Eastern people and deconstruct this racial caricature of what Muslims are. That’s why I intentionally chose to place a Uighur Muslim woman on the cover of the book. It’s not somebody who you imagine would fit how you think about Muslim women.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.