Why We Need Limits on Extreme Wealth

An introduction to limitarianism, and why there should be an upper limit on how much money people can accumulate.

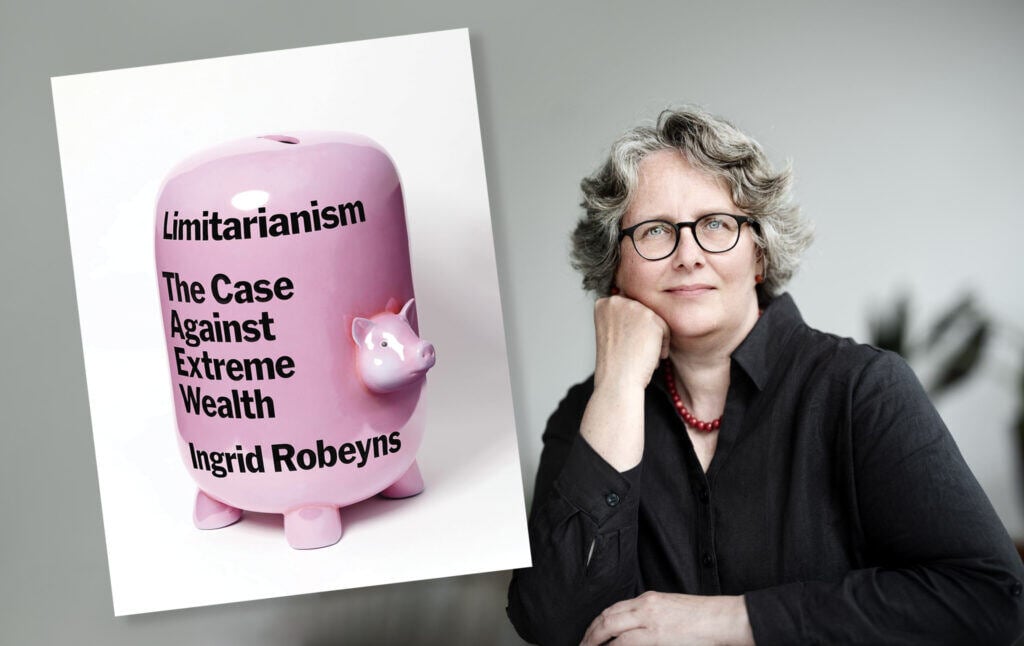

Ingrid Robeyns is a professor at Utrecht University, where she specializes in political philosophy and ethics. She’s the author of Limitarianism: The Case Against Extreme Wealth, a new book which argues for rational limits on how much money a single person can amass. Robeyns explains how the superrich keep everyone else poor, how large concentrations of wealth damage democracy and the environment, and how “limitarian” public policies can become a reality.

Nathan J. Robinson

Let’s start with a common viewpoint here in the United States: poverty is a problem, it’s very sad, we don’t like it when people are poor and suffer, but inequality is not a problem. It doesn’t matter how much people at the top have; it matters how much people at the bottom have. There should be no upper limit to wealth as long as the economic pie is growing and the poor are getting some of it. It doesn’t matter if the rich are getting much richer—they create wealth. Why should we care about the top, the upper limit, that you discuss in your book?

Ingrid Robeyns

There’s a lot of research that has shown that inequality in itself actually has negative effects on society. Unequal societies are more unhealthy than equal societies. My book, and my argument, focuses specifically on the wealth concentration at the top because that causes particular problems. Basically, concentration of wealth means concentration of power and the ability to pollute the environment. There are all these harms and damages that wealth concentration can do.

Robinson

The line I’ve heard before is: the poor are not poor because the rich are rich, meaning that the rich could gain a lot more wealth, and the poor could gain a lot more wealth at the same time. Do you think it is true that the poor are not poor because the rich are rich? Or are the poor poor because the rich are rich?

Robeyns

The research I’ve put together in the book does support the point of view that the poor remain relatively poor, also, because the rich just take a very big slice of the pie. So, it is possible, in theory, that the rich will become rich and the poor would also get out of poverty and the middle classes would rise, too. If you look at this globally, but also within countries whose economies have grown tremendously over the last decades, the rich have taken the lion’s share of what we collectively produce.

Particularly relevant for the U.S., there’s a book by Princeton sociologist Matthew Desmond, and the title of the book is revealing. The title is Poverty, by America. In the book, he attributes the persistence of poverty in the U.S. to policy choices. One of the arguments he makes is that anything that has to do with material policy—housing, fiscal policies, and so on—is a zero-sum game. So, if you give tax deductions to the richest, it means lack of tax revenue for public housing policies or any other policies that benefit the poor.

Robinson

You said “zero-sum” there, and I want to dwell on that for a little bit. I read a book a few years back by a couple of followers of Ayn Rand called Equal is Unfair, and one of the things they said is that wealth is not zero-sum. It’s not like a pie. They call it the “pie fallacy,” the idea that wealth is like a pie: if I get a little bit more, you necessarily get a little bit less. They say it’s not like that because everyone’s amount of pie can grow. But you say that wealth is zero-sum in that there are choices that we have to make about alternate uses. If you’re not spending money on one thing, you’re spending it on another.

Robeyns

Yes. It is true that in economic policies, we have both zero-sum policies or choices, and we also have positive-sum situations. What we’ve seen is that globally, and within the economies of countries that have grown, the pie has become bigger. But then how is that divided? In the book I show that we’ve given crumbs to the poorest.

Robinson

They’re not getting a slice of pie.

Robeyns

No. We’ve been able to lift some of the absolutely poor out of poverty. Because that poverty line is so low, it’s actually not that difficult to pull them out. But the 1 percent has massively increased their wealth. The pie gets bigger, but how is it divided? What are other ways to divide it than the way we currently do?

Robinson

You have gone into the data. There’s this popular website called Our World in Data. Steven Pinker has presented a lot of this data as well. One of the most discussed findings is the number of people over the course of the past decades that have been supposedly lifted out of extreme poverty. This is often the defense given for inequality: yes, we live in a very unequal world, but there are all these people who would once have been very poor, and now they’re not. You point out that in some ways, that comes from just setting an extremely low line so that it’s really easy to push people over it. And in some ways, it’s almost like a magic trick, or it’s almost like it’s not as much of a gain as it’s being presented as.

Robeyns

In all fairness, it is true that the number of people living in absolute poverty has decreased massively. I think that is what the data shows. But there are two big disclaimers to that claim. One is that the poverty line is very, very low. It’s around $2 a day. It’s what economists call “purchasing power parity.” Most development economists say that you should put that line at $11. And then, of course, the number of people who are still living in extreme poverty is much, much higher. So, that is one problem with the optimistic interpretation of the data.

The other one is, what were the possible scenarios we could have? It’s clear that we have a scenario that, for the absolute poor, at least on a global level, is better than it was some decades ago. There were alternative scenarios, where if the 1 percent, and even the 10 percent, would not have pursued endless accumulation of their wealth, we would have had a much bigger reduction in not just extreme poverty, but also just poverty in general. So inequality and poverty are intrinsically related. And that’s logical. They’re both aspects of the distribution of money.

Robinson

So we have a story that says, look at all these people who have been drawn out of extreme poverty. They used to make less than $2 a day, and now they make more than $2 a day—maybe they make $3 a day—and we look at this as a great victory. But what you’re saying there is, there was another alternate world where they didn’t go from $1 a day to $3 a day—again, as you said, in United States dollars. So, what if we didn’t have this kind of wealth concentration, and they had gotten to a much more reasonable amount like $15 or $20 a day?

Robeyns

That’s exactly what it is. These particular data are from Jason Hickel, the economic anthropologist, and the analysis is also from him. One of the narratives that we were presented with is that the increase in income for different income groups has been the biggest for, you could say, the middle classes on a global scale. But he pointed out that this is when you look at percentage increases. If you have almost nothing, and you have $2 a day and go to $4, it’s a doubling of your income. But if you have an income of $50 million a year, and you grow to $55 million a year, it’s not such a big percentage increase. But still, you earned another $5 million. And he then calculated what the absolute increases were. It shows that the richest have benefited most from the increasing “pie.”

Many of our folk wisdom approaches to economics are very individualistic, but we produce the pie together. We should go back to the founder of economics, Adam Smith, who showed that we, in the end, produce these things together. It’s a question of distribution.

Robinson

You pointed out that when additional wealth goes to the top, it’s doing less work than if it goes to those at the bottom. In a crude utilitarian analysis, how much use can any given person get out of additional wealth? If you’re a billionaire, each additional dollar is virtually meaningless, whereas if you are a person who is earning $2 a day, each additional dollar is really important to you. So, as wealth is created, that should make us lean towards favoring it going to the people with the least.

Robeyns

Yes. There’s an old finding from both economics and political philosophy. It’s called the declining marginal utility or value of money, which means that the more you have, each additional dollar is contributing less to your well-being, happiness, and flourishing. And of course, one could ask, then why do the superrich keep wanting to accumulate money? One of the findings from the ethnographic and sociological research is that among the superrich, there’s a small group that is really deliberately giving away their money. But the largest group is really focused on accumulation. The available psychological research seems to suggest two mechanisms: one is comparison—it’s a status issue where you compare yourself with the next person on the Forbes list, and you just want to have more than your millionaire or billionaire neighbor. The other one is that it’s like an addiction—you just seem to always want more, and there’s a shifting of the goalposts. And there is a very interesting bestselling book called The Psychology of Money that documents this: if you keep shifting the goalposts, you will also sometimes do stupid things, or sometimes even evil things, to get to the next goalpost. One of my arguments is to question why you should want to shift the goalposts; you already have everything you could reasonably want for a really good life. This is not a popular claim. Our culture says, literally, the sky’s the limit. The approach I’m trying to defend, which goes back all the way to Aristotle, is that no, the sky shouldn’t be the limit. There’s a limit to how much we should want because a good life is also a life lived within boundaries.

Robinson

An interesting argument that you make in the book is that this ceaseless pursuit of accumulation, where nothing is ever enough, ultimately harms the superrich themselves. You cite the wonderful book Generation Wealth by Lauren Greenfield, who studied the lives of the rich and their children. Oftentimes, being a child with extreme wealth has damaging effects. This idea that meaning in life comes from improving your bank account is not good for people.

Robeyns

That’s true. For my book, I interviewed multimillionaires. And, of course, I must make the disclaimer that the multimillionaires I interviewed are not representative of all millionaires and billionaires. But they actually confirm the point that if you grow up very rich, you might not know whether what you accomplish is really your own since everything has been set up for you to succeed. If you are just living an ordinary middle-class life, or even living in poverty, any success you achieve will require you to really put in a big effort.

Robinson

We often hear incentives invoked as an argument for allowing the accumulation of large-scale wealth: if you tax away people’s money, they won’t want to work hard. But it’s also true that if you inherit a pile of money, that creates pretty bad incentives, too. Why should you do any work?

Robeyns

That’s true. I’ve also done research on the ethics of inheritance. In this respect, both economists and political philosophers agree that inheritance taxation is one of the most rational taxations we can have precisely because of what you say. There are no incentive effects—actually, no, there is an incentive effect in the bad sense. You will basically say, I get that big amount of money, and I’ll just stop working. But also if you tax it, it doesn’t really make a big difference to how much people will save. And then there is a fundamental philosophical argument that you don’t deserve inheritance because you did nothing to get it. But the funny thing is that in the case of inheritance taxation, the feelings that people have are very oppositive. I think the reason why we have these strong emotions against inheritance taxation has to do with family ties. And some people may also have these strong emotions because they think that the government is evil and so they are against any type of taxation. But I think most people seem not to realize that the vast majority of people actually don’t get an inheritance. So, the problem is not so much with inheritance per se. The problem is that some inherit nothing, and others inherit millions, and then you get unequal opportunities from the start.

Robinson

Once, I looked up what Ayn Rand said about inheritance. I’m always curious about how you can justify something that seems pretty impossible to say that you earned or deserved. And essentially, if I recall her argument correctly, she said something like, yes, it’s completely arbitrary, and there’s no fairness to it. But, she said, why does the state have the right to take it away? So, it’s an interference in private arrangements within families. Inheritance might not be fair, but there’s no reason that society should put that wealth to alternate uses. How do you respond to that?

Robeyns

I can see that reasoning. We shouldn’t be naive about the state and the government because actually, many countries have governments that are imperfect and, to put it mildly, sometimes are pretty disastrous. So, what I propose in my book, and also in my scholarly work, is that we limit the amount you can inherit, and all funds from inheritance taxation go a hundred percent back to the citizens. It doesn’t go to the state; it goes to those who would not inherit anything otherwise. That means that we will provide for all people. I would give it to young people because they need it most to get a kickstart in life, either for the beginning of a mortgage, to set up a small business, or something like that. It will give all of them a foundation to build their lives. So, you can think about designs that keep the state out, and that might be an answer to the libertarians.

In political philosophy, we have what we call the right-wing libertarians and the left-wing libertarians, and the left-wing libertarians actually favor full abolishment of inheritance. So, in my proposal, I want to accommodate to some extent the fact that there is this relationship between parents and children, or an adult and a significant other person. I do want to accommodate the fact that money is not just purely transactional but part of relationships. But I just think we should limit it because inequalities in inheritance create problems and also undermine equality of opportunity. I think everybody favors equality of opportunity.

Robinson

Yes. You hear that from right to left. People often use that as a piece of rhetoric without thinking about what it would really mean to have equality of opportunity, which will require quite a radical restructuring of economic distribution.

Robeyns

Also, I argue in the book that having a limit to how much wealth you could have—on the assumption that what would be collected would be used in a way that increases the opportunity of the worst off—would increase the total opportunities of people. It would also bring us much closer to this ideal of equality of opportunity. And equality of opportunity is really, as you rightly say, a principle or a goal that everybody seems to support. We just haven’t thought through what this requires from us.

Robinson

I keep thinking back to what you’ve said about how inequality squanders possibilities. We’re hurting ourselves, ultimately. If the people who don’t inherit anything did get some amount of money, they could use it to start an enterprise, for a down payment on a house, and they could make their children better off and give them a richer life—maybe one of them could quit work, and they could be a better parent because they’re not working all the time. There are all kinds of social benefits that arise when we give money to people who don’t have it.

Robeyns

Again, this follows from the declining marginal utility of money. That is an important premise under my argument. At some point, if you already have a lot of money, more money only adds to the status and psychology of the person. It doesn’t really make a difference materially.

Robinson

I think it’s such an important concept, this declining marginal utility of money. People might think of it as a technical economics term, but let’s understand it in plain language. Wealth given to people who are living on the streets means so much more to them than, say, the millions that Elon Musk has made in the time we’ve been speaking.

Robeyns

Yes. When I was a student, I started out with no money, and now I’m a professor and have a very decent salary. When you don’t have much and then earn enough money to be comfortable, you can really do a lot with it. What you see prudent people do is to start saving. Of course, that’s logical. You want to have a cushion for when something happens. In most countries, you have to save for your pension. But that’s the middle classes. If we’re talking about the rich, suppose you have covered your pension needs and your healthcare needs, and then you have a million, another million, and another. What do you do? It’s just a number in your investment account.

Robinson

We’re talking about how, at a certain point, this additional wealth becomes meaningless and could be put to other better uses. But in the book, you also discuss how extreme wealth confers a lot of political power. This concentration of power through concentration of wealth is very damaging and dangerous. You discuss the fact that it’s not just that a rich person gets a lot of numbers on a spreadsheet. It’s also a bad idea to allow people to have that much power.

Robeyns

Absolutely. Political scientists have done very important research by comparing different countries and the way that the superrich basically undermine the principle of political equality. So basically, one person, one vote is equal political influence. I quote in the book something Donald Trump said before he was in politics himself. He used to give money to both the Republicans and the Democrats. The journalist asked him, Why do you do this? And he said, Because no matter who is in power, I will have somebody to call up, and they will do what I ask of them. Of course, this is rational. It’s rational to assume that if people give large amounts of money, they get favors back. That’s one mechanism.

The other mechanism is lobbying, and it’s a very important one. If you have money, you can buy a lobbyist, and they will try to get the policies or the changes that you need. And in the U.S. in particular, we’ve seen that the changes in the fiscal system over the last decades have been to the benefit of the richest. There is a book written by the U.S. activist group Patriotic Millionaires called Tax the Rich! They document how the richest in the U.S. lobbied for changes in the fiscal legislation that basically make it so that the richest pay fewer taxes than the next deciles. This has to do with the differences in how much Americans pay in taxes on income from labor versus capital gains or profits. And so, that’s another way in which if you have money, you can use it to undermine democracy.

Robinson

Another thing is that you can essentially buy your way into a country and across the international borders.

Robeyns

Yes. There’s this phenomenon called golden passports. If you have enough money, you can just buy a passport, and the world opens up to you. The passports in demand are European Union passports. If you have a passport, for example, from Malta, you can live and work in any EU country. There’s the case of Peter Thiel, who is German in origin and also American. He acquired New Zealand’s citizenship, and the reason is that he wanted to buy a plot of land so that in case of catastrophe, he could take his private jet and fly to New Zealand, and he could be in his own bubble next to unspoiled lands and water and survive the apocalypse. But the problem is that in New Zealand, to buy land, you have to be a citizen. It’s very hard for anybody to get land there. But he managed. He was in New Zealand for 12 days before he acquired citizenship. So, political groups then started to complain, and they found out that the reason he was granted citizenship was because of his “service to the economy” of New Zealand.

Robinson

In other words, being rich. And this is especially tragic and cruel when you see the number of people without any money who are fleeing violence and poverty and trying to get into the United States on the southern border. All they want is to come and work and live a peaceful life, and they can’t get across the border. But the moment you flash the wallet, and you’re Peter Thiel, they say, sir, what country would you like to live in?

Robeyns

It’s really true that we have different rules for poor people and for the superrich.

Robinson

And our grotesque distribution of wealth is now causing a planetary catastrophe.

Robeyns

Yes. In theory, it is possible to be superrich and not to use that money to damage the environment and the planet. But that’s a theoretical possibility. What we see is that the superrich pollute vastly more than other groups with things such as private yachts, mansions, and multiple homes. And in the case of private jets, perhaps we should just abolish them. As long as we don’t have a carbon-neutral way to fly privately, I don’t see how they can justify it.

Robinson

Right. It hurts the rest of us. You could justify banning private jets even on a free market theory, which is that you’re allowed to regulate markets when there are these externalities, these harms and costs that your activity within the market imposes on others, which obviously private jets do.

Robeyns

What standard economic theory says is that if you internalize the negative externalities into the price, which we could do by having a carbon tax, then the problem might be solved. But actually, that particular theory was built on the assumption that inequality was not as significant. Once you have significant inequality, you might actually have to go to models of rationing rather than including the effect of the price. So, this is also something like this idea of internalizing the externality in the price, which I’m all in favor of. But with somebody like Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk, suppose we say that they should pay $100 per every 1,000 miles they fly. They will just laugh at us and throw some money.

Robinson

They’re not going to change their behavior. They’re just going to pay the fee because it’s meaningless to them. So, the idea here is, we will discourage them by forcing them to pay the costs of the harm they’re doing. But if you can just pay for harm, then….

Robeyns

It’s what economists would call the income effect. They have so much income, and in their case, also wealth, that it’s not going to affect them. It’s going to affect the middle classes, who will no longer be able to fly, and I think we should all think twice—or three times—before flying. In the case of politics, you have another measure that you could advocate, which is to try, with regulation, to make sure that money from the privileged position in the economic sphere harms your privileged position in the political sphere. One way to do this is by having campaign legislation. My own country, the Netherlands, recently introduced a law that each person can maximally give 100,000 euros per year to political parties. I think if you were to apply this to the U.S., there would be plenty of people in trouble. But they’d try to find ways around it. They’d start a foundation, and all these entrepreneurs would give a million to it—a not-for-profit outfit or something like that, similar to the super PACs in the U.S. As long as some people have such a disproportionate amount of money and power, they are going to try to evade and change these regulations.

Robinson

Ultimately, you come to the conclusion that there has to be an upper limit on the amount of wealth that can be possessed.

Robeyns

That’s my argument. There are important values like the survival of the human species on Earth. So, it’s logical that sustainability, political equality, democracy, and having our basic needs met are just so much more important than the addictions of the superrich. I do think we should take incentive seriously, in a sense that, yes, people who work harder should be able to earn more and so forth. But the incentive argument is also not to do so endlessly. We can also find ways to reward people and to show our respect for what people have done in other ways instead of only letting them accumulate more money. The whole system of giving prizes in academia, of giving honorary degrees, for example, is to show respect, admiration, and acknowledgment for the work that people have put in.

Robinson

Most people who innovate would say that they don’t do it for the money, anyway.

Robeyns

Yes. But then it’s in tension with the argument that we shouldn’t tax too much.

Robinson

If you tax me too much, I won’t do it. But also, I don’t do it for the money. To conclude here, you talk in the book about how when you start to talk about limits, people often mischaracterize you and say, this is communism. But what you’ve been saying is that, even if we accept the idea of a limit, the limit can still be set quite high. You can still live very comfortably within the limit that we’re talking about. It is possible to have a range of incomes. It’s still possible to have some level of inequality. Where do you think the limit ought to be?

Robeyns

This is in part based on empirical research I did with colleagues, where we did a survey among a representative sample of the Dutch population. We basically gave them descriptions of material lifestyles, where each case was in increasing amounts of wealth. We asked them to decide when somebody has too much. People do draw that line at different points, but almost all of them do draw the line somewhere, which means that the conceptual idea of having too much makes sense. It’s not just an academic idea. So, based on that research, I argue that for the Dutch context, one doesn’t need more than one million per person to lead a really good life. But I say it’s for the Dutch context, and we have two types of security that I do not think all Americans have. We have a regulated healthcare system. It’s not like the British NHS. It has private providers, but it’s highly regulated and also subsidized by the government. And we also have, importantly, a collective pension system. And these two things, of course, take away two really big sources of anxiety and worry among the citizens. So, I can see that in the American context, you may have to put a higher limit.

Robinson

Unless we get universal healthcare.

Robeyns

Yes. I think it’s much more rational to have universal healthcare and to also think about having a pension system at the poverty line, where people can still save for top-ups.

Robinson

People here do feel that they have to accumulate because, in part, they feel precarious. They feel like it could go away tomorrow, and they could end up on the streets.

Robeyns

In the Netherlands, we pay a monthly fee for healthcare. It’s fixed. And so if I were to have a very serious disease—cancer or something like that—it would not affect me in financial terms. I would not have to pay extra, and that just gives me peace of mind. It’s actually rational to pool the risks of bad luck. That is a finding from economics. If you have certain risks that are spread over the population, it’s much more rational to pool those risks. And I think we should do that both with healthcare costs and pensions. How can you know how much you will have to pay for your pension? Because you may actually die at 67, but you may live until you’re 99. It’s much more rational to have those systems in a traditional welfare state.

What I’ve said so far is what I think you need for a flourishing, good life. And then there is the question of political limits and how we should organize economic systems so that we try to make sure we end inequality. This is difficult for me to guess because I don’t have solid research here. But in the book, I’ve proposed 10 million. That gives you the scope for the incentives for people to innovate, to work hard, to take risks, and so on. People may argue that 10 million is too low.

Robinson

But it’s a lot of money.

Robeyns

But it’s not one billion. So there are people, including Bernie Sanders, who say we shouldn’t have billionaires. I think that statement is not ambitious enough. It’s not just that we shouldn’t have billionaires. We shouldn’t have decamillionaires or semimillionaires. It’s really not necessary to have so much money.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.