Manifest Destiny in Space

“Astrotopia” author Mary-Jane Rubenstein discusses the dangerous colonial myths about the necessity of conquest and expansion, and how they show up in billionaires’ rhetoric today.

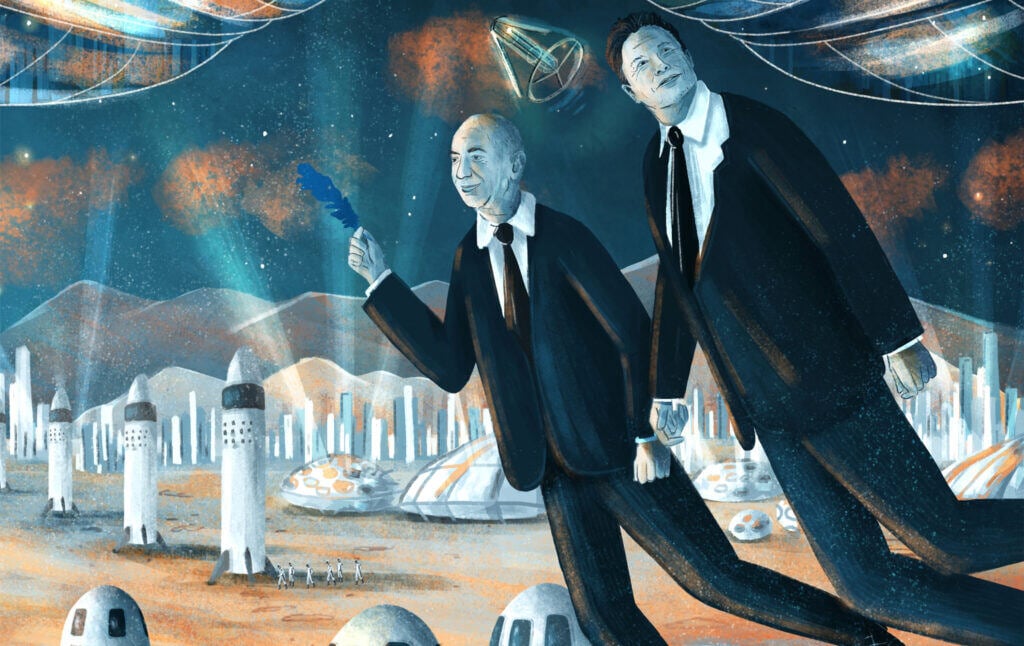

Mary-Jane Rubenstein is a scholar of religion, but her latest book is about Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and the “corporate space race.” For Rubenstein, the promises that these men offer of a human future in vast colonies on Mars or the moon have much in common with religious myths of a “promised land.” And like these other myths, the ideology underlying Silicon Valley’s space colonization missions can be used to defend unjust acts in the here and now to serve the glorious long-term destiny of the species. Rubenstein’s new book, Astrotopia: The Dangerous Religion of the Corporate Space Race, looks at the ways in which stories about great destinies have been used to rationalize conquest and exploitation. Rubenstein worries that just as “Manifest Destiny” was used as an excuse for genocide in the United States, plans to “expand into space” will be used to justify trashing Earth and ignoring the most pressing issues of inequality in our near-term future.

Rubenstein is not against utopianism, but she argues that Silicon Valley techno-utopianism is fraudulent, using the rhetoric of science and reason to disguise the fact that its promises are actually unscientific and unrealistic. Instead, she advocates that we get our ideas for a beautiful human future from a diverse array of other sources, from feminist science fiction to indigenous thinkers. Rubenstein offers us a starting point for thinking about how we might forge a path for our species that is egalitarian and humane. In this conversation with Current Affairs editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson, Rubenstein discusses the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015, utilitarianism, the Land of Canaan, privatization, longtermism, Ursula Le Guin, and much more.

Nathan J. Robinson

What is a scholar of religion doing writing about the corporate space race, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, SpaceX, and the privatization of space? What does any of this have to do with religion?

Mary-Jane Rubenstein

This is a great question. By the corporate space race, what I mean is that it’s important to say that corporations have always been involved in some way with space exploration since the beginning. Boeing and Lockheed Martin, for example, have helped advance U.S. missions in outer space. In the last seven to twelve years, however, increasingly, the U.S. space sector in particular has been turned over to private interests, with legislation that has increasingly given stipends and government contracts to companies that are willing to do much of the heavy lifting for us.

This is an era in which enormous corporations are not only competing for government contracts, but increasingly setting the vision of what life in outer space is going to look like. So, they’re not just running pizza up to the International Space Station for us. They’re giving us a sense of what we ought to be doing in space, and why. And what we ought to be doing in space, according to these actors, is to start a new economy in space. As you probably know, the Earth is a finite thing—there are finite resources, space, and land on Earth. If profits are going to keep increasing, we need more stuff. So, the argument goes, we’re going to have to go beyond the Earth and start a new economy out there and find more resources. We need more metals, energy, and so forth. This is primarily an economic project of having more land and resources, just like earthly colonialism was.

When Europe needed more stuff to industrialize itself, it started taking over other people’s lands. Well, now everybody else’s lands are already taken on Earth, so we need more elsewhere. Economic projects that involve taking over new stuff require—especially if they’re going to be as extraordinarily difficult as, say, this one or the transatlantic journey—a big story to get people invested ideologically. And increasingly, what we’re getting from guys like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are these grand stories of coming salvation and upcoming disaster: we’re using too much energy, the planet is going to die, and then a promise of salvation somewhere else. It’s a big story of humanity about to be destroyed on the one hand, and going to another land where things will be fantastic on the other. It gives the whole thing a religious patina that I think is important to understand.

Robinson

Yes. When you start to look into the statements that people like Bezos and Musk have made, Bezos has this insane-sounding plan—he’s a little quiet about it—but when he talks about what he’s actually planning or hoping for what he sees the future as, he talks about having trillions of human beings in space. There will be thousands of Einsteins, and we’re going to move some portion of the population off of Earth to preserve it as a wildlife park, probably for the rich, with the rest of us working at Amazon warehouses in space. And Musk’s vision, as you point out, is a little different. He explicitly says, “Fuck the Earth, we’re going to Mars—Mars is where it’s at. We don’t need Earth.” Could you tell us more about the stories that are being told by the people who are leading the new space race?

Rubenstein

Yes. I’ll focus on Musk and Bezos because they’re the characters I tend to think of as prophetic or messianic in some sort of way, these self-appointed folks who chastise us for what we’re up to and tell us there’s a different way forward that involves moving to a new land. I think Musk’s vision is most familiar, so I’ll start there. The Earth is eventually going to become completely inhospitable to human life, whether because an asteroid might hit and wipe out humans like what happened with the dinosaurs, AI robots go wild and destroy the human species and decide the Earth is theirs, or nuclear war will abolish us all. Something is going to wipe out humanity. So, unless we have a little reserve of humans somewhere else, this massive disaster on earth will wipe out not only all of humanity, but all records of humanity. The idea is to get a backup community somewhere off the planet. For Elon Musk, that backup community is going to be on Mars.

Why Mars? It has more elements and gravity than the moon and is better than any other planet out there. Venus is 900 degrees Fahrenheit. You’re not going to put anybody on Venus. Mars is cold, but not as cold as Venus is hot. So, we’re going to go to Mars, and we’re going to bound around in one-third gravity, and, yes, you can’t breathe and your blood will boil, but we’ll figure that stuff out and get it right and have a backup colony for the time when humanity is destroyed on Earth.

Bezos has a totally different vision. He also believes that there’s a disaster coming, but a different kind. Specifically, he’s worried that we’re using too much energy, and if we want to keep living the way that we’re living—which is to say with high-tech devices, first-rate hospitals, fantastic universities that leave the light on all the time, everyone has one or two cars and three refrigerators—there isn’t enough energy. All the solar panels in the world are not going to give us enough energy, and, of course, we don’t have enough oil in the ground or gas in the mountains. Therefore, Bezos says, we do have to go to space.

But Mars is terrible. It’s too far away—it takes three months on a good day, five or six months on a bad day, to get to Mars—and inhospitable. How are you going to warm that planet up? You can’t breathe the air, so what should we do instead? Well, we’ll build little space pods close to Earth, like where the International Space Station is, or a little farther out, so you can get there pretty easily. There will be gigantic shopping malls, totally climate controlled. You can import anything you want and mine asteroids or the moon to get some water. Everything’s going to be 72 degrees Fahrenheit all the time—completely perfect. There we will be, living in our perfect space colonies. And as you’ve said, in the meantime, says Bezos, with heavy industry and most of the human species relocated to the space pods, Earth can have a chance to heal and regrow to become a gargantuan cosmic park equivalent to a national, or cosmic, park—a protected area. That’s his idea.

Robinson

It’s worth noting that these two men consider themselves to be devotees of science and reason. The stories that you’re describing are justified through, as you mentioned earlier, an economic argument. This is an argument that the resources are finite, so we have to do this and it makes logical sense. When we examine these stories against factual reality, we know Elon Musk is notorious for making grandiose promises that are not well grounded in actual science despite using the rhetoric of reason and rationalism, whether it’s promising to build a submarine so small it can rescue children from a cave or to build tunnels under various cities. There was an exposé in the Wall Street Journal recently indicating that Musk’s Boring company has born nothing, despite promises. Is it true that we have good reason to believe that these grandiose stories grounded in the rhetoric of science and reason are closer to being giant myths than they are real promises of things that are on the cusp of happening?

Rubenstein

Yes, I think this is true. And yet, the grandiosity of the vision and the self-righteous humanitarian claim of “trying to save all of humanity,” as Musk will say, are very difficult to criticize. The ideas can do lots of damage in the meantime. Because then, if you buy into the vision and presumption that the Earth is done and toast, and we need to start putting our resources into the next place, you can complete the trashing of Earth in the process of trying to enact this extraordinary vision—whether it ever actually comes true. So, whether it’s going to happen, the vision is dangerous.

Robinson

It also rationalizes inequality. Didn’t Musk talk about only trying to amass resources so he can expand the light of humanity to all the distant stars?

Rubenstein

Yes, that’s what he says: I am amassing resources to ensure the immortality of the human species and to make sure that we get to the stars. There are many things one could spend obscene resources on, including providing clean water in most parts of the Earth. And yet, both Musk and Bezos have said they can’t think of anything to do with their extraordinary fortunes other than to move us into outer space.

Robinson

Yes. But Bezos said he literally can’t think of any way to deploy his winnings. And then when he came back from space, he thanked all the Amazon workers and customers for paying for this through what they weren’t being paid. So if you tax them, the argument is that you are actually behaving immorally by undermining the prospects for the glorious human future.

Rubenstein

That’s exactly right. Again, it’s a vision that always has the ideological upper hand, because anything you do to stand in its way seems to set you against the massive abstraction of the future of all of humanity.

Robinson

Yes. Who wants that? You talk about the ideology of longtermism that has become popular among Musk, the Effective Altruism community, and in Silicon Valley. It’s supposedly grounded in rational utilitarian morality that almost comes to the conclusion that caring about what we might consider our most pressing problems is immoral compared to building the glorious future Astrotopia.

Rubenstein

Yes. I’ll just put my cards on the table here and say it’s a terrible position to believe that it is more important to secure the survival of a trillion hypothetical beings in the future than a few billion actual beings now. Therefore, rather than putting your money into development in developing countries, or into access to clean water, healthcare, or universal basic income for people who are here, you should really give the money to the entrepreneurs who are looking toward the future of, again, some major abstracted version of humanity.

Robinson

It’s easy to critique this kind of utilitarianism as building a dystopia under the guise of building a utopia. But, one of the values of your book in particular is that you contextualize this argument by looking at the history of the rhetoric of promised lands, such as Manifest Destiny. The idea is that we have some kind of either God-given destiny or racial superiority that justifies the devaluing of the present, or of certain lives, in the service of some grand thing.

Rubenstein

Right. To go back to your first question about why somebody who studies religion is writing a book about this space race: it was just so clear, the minute I started paying attention, that these are the same rhetorical and ideological moves that justified the conquest of the New World (initially by Spain and then other European powers), the expansion of white-descended people across the American continent, and now the expansion of humanity into space. In those terrestrial stories, the story of the discovery of the so-called New World and the westward expansion, you can see very clearly that any reservations that ordinary people might have had about taking new land are explicitly precluded or shot down by endorsements from the Church.

It is Pope Alexander VI who gives the so-called New World to Spain. He just gives it to them—”It is yours.” And so the shifty or questionable business of taking other peoples’ lands, and displacing and even murdering or enslaving them, is swept under the rug of conversion and “saving souls.” Right now, we’re saving their souls eternally—that’s longtermism. You want to think about the original longtermism: it doesn’t matter what happens to your body here on Earth, because we’re saving you. So, it’s okay if you’re enslaved, because your soul will be saved. We could call it the Christian version of longtermism. That is what justified the European conquest of the globe.

Robinson

Could you talk about the biblical promise of the land of Canaan? You said it almost became the title of the book until you realized that nobody remembers what the land of Canaan was about.

Rubenstein

The story of the land of Canaan is a story of God having chosen, totally arbitrarily, a human being named Abram, and saying to him, “Your people are going to be my people, and I’m going to bless your descendants. You will have many children, and I’m going to give you this land.” The first couple of books of the Hebrew Bible are a chronicle of the descendants of Abraham [formerly Abram], then on their torturous way into the Promised Land, first under Moses, and finally, under Joshua. And, of course, when they get to the promised land, the Israelites are told, “When you’re heading in there, you’re going to find this land is yours, but it’s not totally empty. It’s the land of the Canaanites, Amorites, Jebusites, Hittites, etc.” And God says, “When you get in there, make sure that you kill them all. Destroy their temples and everything else, otherwise, you might fall into idolatry.”

It’s important to say that it seems like this didn’t happen. It seems like there was no conquering of Canaan, that when the Israelites moved into the land, they settled the way that anybody else does when they’re not looking to take over. But it becomes a biblical story to justify the special position that Israel and the people of Israel have as God’s people. The problem is not so much what happened to Canaan, because what happened to Canaan, again, doesn’t seem to have happened. The problem was what this story does in the early modern period. This Jewish inheritance is, in part, picked up by Christians, and then, in particular, by imperial Christianity. In the hands of nominally Christian leaders, the story of the conquest of Canaan becomes a blueprint for the conquest of the so-called New World. America is God’s New Jerusalem: this is now the land that God has given you, and just as you were supposed to destroy the peoples of Canaan, you should also, as we can see in early sermons, eliminate the Native inhabitants of this land, lest we fall down on the task God has given us to make this a godly Christian nation.

Robinson

I imagine there might be Palestinians who would say that it’s not so much a matter of whether it happened but when it happened and who it happened to.

Rubenstein

Right. When I say that it didn’t happen, I mean in biblical history.

Robinson

One of the things that comes across very strongly in your book is why the narratives of Manifest Destiny are so compelling. They are deeply grounded in morality and inevitability. It has to happen; it must happen; it’s good that it’s going to happen. The people being driven away or killed either deserve it or it’s actually good for them, and we’re creating something that is more beautiful than anything that exists or that we could even conceive of.

Rubenstein

Which, again, is the center of longtermism’s promise: whatever we’re building is worth the perhaps unsavory means that we’re using to get there.

Robinson

Some people, I suppose, will put Stalinism in the same category?

Rubenstein

Absolutely. It doesn’t bode well for our astro-preneurs.

Robinson

You’re very good at laying out how these ideologies are being pushed by people who have self-interested reasons to push them, and why we might critique these things. Is there an alternate vision for the future in space? These things, as I’ve just said, are very beautiful and compelling, so where do we begin to construct something else?

Rubenstein

First, it’s important to get clear about what the problem is with carrying this model into outer space. It’s tricky, because on the one hand, the story is the same. It’s the same alliance between private interests and large nation-states, covered over with a religious candy coating, sending us out to conquer a new land. On the other hand, of course, what you’re going to hear from “conquest enthusiasts” is that it’s a completely different situation: there are no Indigenous people in space. It’s actually empty. We can take whatever we want, and we’re licensed to use it however we would like because it doesn’t clearly belong to anybody else. Our exploits in earthly colonialism were wrong, but we can do whatever we’d like in outer space because, again, there’s nobody there.

There are a couple ways to respond to this. We know, at the very least, that the method of extracting as many resources as possible in order to maximize profit has not been good for the land on Earth. It has encouraged mining, which has the worst labor practices imaginable. If you want basic job security, worker’s compensation, and a safe and healthful workplace, you don’t work in a mine. So, what is that going to look like out in the wider solar system where workers will have no access to air, water, and basic survival independently of their employers? Are these really the labor practices that we want to export into the cosmos? Are these really the practices of maximum profiteering that we want to export to other planetary bodies? Having ransacked one planetary body, do we really want to do it everywhere else? Is that a great idea?

So rather than saying there are no Indigenous people out there, why not talk to Indigenous people who have found ways, historically, of living on the land without ravaging it? There are numerous peoples across the globe who found ways to live on land without ravaging it. Why not learn how to do that, instead of taking this model of maximum profiteering out into the universe and thinking that just because it’s the fastest way to do it, it’s somehow the best way to do it?

The first step is listening to the examples of people who know how to live with and on the land. Of course, these are not just Indigenous folks. I know an abbey of cloistered nuns about an hour away from me who know how to live on their land and tend and care for it respectfully without ransacking it. We could talk to those nuns and ask them, “How do we do outer space better than we’ve done it?” There are all sorts of people we can talk to, but I don’t think that the billionaires are the right ones.

Robinson

I worry about humanity meeting aliens before we leave capitalism behind. But there are people here that these men intend to export to their outer space Amazon warehouses, which will be governed privately. I think Elon Musk has already said that he doesn’t intend for any earthly government to have its damned labor laws enforced on Mars. And of course, there are the people on Earth whose planet, as you mentioned, is being destroyed. It doesn’t matter if there were people living on the land where they built the pyramids if it required a large number of lives to build them.

Rubenstein

Right. This is the issue. Also, for what it’s worth, it is not a universally acknowledged truth that there are no beings in outer space. You can ask an astrobiologist, and for them, it’s going to be likely that there’s life out there somewhere. But even in our immediate cosmic neighborhood, according to some communities, there are actually people on the moon, and the reason you can’t see them is that they are spirits. There are people in the Milky Way and ancestors on planetary bodies and in the space between planetary bodies, and our increasingly disrespectful behavior of trashing low Earth orbit—dumping tons of rocket fuel into our near neighborhood—is not only deeply disrespectful but actually harmful to the ancestors who live there.

Robinson

But even if you didn’t hold the position that there were people there, you could have a different set of values that simply value the moon. You talk about how, if we think there are things that are sacred and beautiful—for example, a mountain—then mountaintop removal is barbaric, even if we don’t have a conception of the mountain as alive, which some people might. Jeff Bezos might dismiss what he calls “the rights of rocks,” but some of us care about the world we’ve been given.

Rubenstein

Yes. You don’t have to believe a mountain is somehow alive or personified in order to respect it as beautiful and as having some kind of import in its own right. But again, some people do. It would also not be unthinkable to say, I owe this mountain respect insofar as my neighbors think that mountain is sacred, even if I don’t think so. If my neighbors who have some kind of relationship to this mountain think it’s sacred, then I won’t frack it, either. It’s just a basic respect for the values of other people.

Robinson

Or I won’t carve the heads of presidents into this mountain. Could you talk about what we can learn from the writings of science fiction and fantasy authors? You cite Octavia Butler, N. K. Jemisin, and Ursula Le Guin and a number of their stories which you feel illuminate and make very strong critiques of the corporate space race, but that also show us the values that we ought to embrace instead.

Rubenstein

When I teach this material, I will often get to a point with my students toward the end of the semester where I will ask them, “If you had the choice either to live in an extraterrestrial shopping mall under the dominion of Jeff Bezos and have as many devices and as much power as you’d like, or to stay on Earth and use less stuff and very little modern technology, which would you choose?” They will, almost all, reluctantly—but clearly—say, “I’m going to go with Bezos.” And when I ask them, they say, “Look, I’m not proud of this decision.”

Robinson

That’s what they say?! I did not think that was going to be the answer.

Rubenstein

Absolutely. Even forest bathing students who are environmental studies majors will say, “Yes, I think I’m on the space pod.” But when I ask them why, they say they don’t think it’s possible to live with less stuff. You can’t convince people to give up their stuff. And it’s at this point that I remind them what Fredric Jameson said: “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism.” It is easier to imagine living without the Earth, our entire means of subsistence, than it is to imagine living without an iPhone or something like that. How does that become possible?

What it amounts to, I think, is a failure of imagination. What we need to do is to imagine better, because we know it’s been possible. People have lived for tens of thousands of years without the crap that we have. We know what’s possible, so what we need are people who can retrain our imagination to allow us to see, think, and eventually live in ways that are different and orthogonal to the ways that we think are possible right now.

This is all a very long way of saying that the reason I reach for science fiction and speculative fiction—particularly the work of feminist authors, authors of color, and queer authors—is that these authors are not constrained by the possible, the actual, or what seems possible. They are set free to imagine what’s genuinely possible, which is to say, with the stuff that seems impossible from wherever we are. They don’t have any commitments to maximizing profits or to the laws of gravity—they can decide what they have and don’t have commitments to. And then, starting not from scratch, but from their values, what kind of society do we want to build?

N. K. Jemisin can start from her values and say, “What would it look like to build a city in which citizens care for one another?” Let’s start from that value of mutual care and build a city. It can be anywhere, and I don’t have to make sure that it’s maximizing profits. So, I think that fiction gives us the wherewithal to realize that we can actually do a lot more than we think we can, and the field of what’s possible is much wider than we worry that it might be.

Robinson

From your title Astrotopia, people might assume you’re critiquing these utopian ideologies of a great promised land as a general critique of utopianism. But I think it comes across in the book that there is great value to dreaming dreams that we might think of as impossible or radically transformative.

Rubenstein

Absolutely. We need to get clear about the values driving our utopian visions. We have to have ideals and to decide that it’s possible to build a more just community than any community that we currently have and to work for it. What I’m worried about is utopianism that’s not actually utopianism, a kind of utopian flavor coating the same old stuff. What Bezos and Musk are selling us is the same old system of dominion, of rich white guys getting richer and whiter, especially because they won’t have access to the sun. It’s just the same thing burnished with a promise of salvation and thrown out into the stratosphere. Go for it, build a utopia, but get clear about what your values are. Don’t just sell me the same thing in the sky.

Robinson

There’s a fraudulence to it where it involves presenting all the upsides and ignoring all the people who are going to experience the downsides. I wanted to conclude by talking about some of the contemporary events that you draw attention to that could shape the human future in space. You bring up a piece of legislation that I don’t think anyone even noticed the existence of: the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act. You bring up the privatization of the space program and the direction that the future could, and is starting to, take. Could you talk about things that are happening that we ought to pay attention to that will determine our long-term destiny?

Rubenstein

So, the things that are happening: the first was Obama’s 2011 canceling of the Space Shuttle Program. It was at this point that he said we’re basically going to have to turn over the space sector to the private sector in the same way that private companies operate airplanes, buses, and, for the most part, trains—private companies are going to have to start operating spaceships. That was a major decision. In 2015, we got the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act: it ensures that anybody who “recovers” a “resource” from an extraterrestrial body—like the moon, an asteroid, or Mars—has the right to keep, sell, and transfer that resource. This was a response to some worry, in relation to the privatization of space, by entrepreneurs that an international treaty called the Outer Space Treaty dictates that no nation can claim any planetary body—like the moon, Mars, an asteroid, or even a part of an asteroid. The entrepreneurs were saying in the early 2000s, “If we’re not allowed to claim part of an extraterrestrial body, then are we allowed to claim the helium or water that we find there?” The Act says you can’t claim the land, but you can claim the stuff in the land.

Again, we have an international treaty that says you can’t claim the land, and then an American piece of legislation that says you can take the stuff within the land. A number of members of the international community describe it as absurd: how do you claim within the land without claiming the land? If you’re going to sink a mine on the moon, you’re going to have to protect that mine and surround it with space force guardians. You’ve effectively claimed it—even if you say you’re just using it—because you’re not going to let China into that space. You’ve effectively claimed it. The U.S. says, Nope, we are totally in agreement with the treaty.

The problem is, nobody can hold the U.S., China, or Russia to laws they make locally that get them out of international agreements. When the nation of Botswana says they disagree, the U.N. says, “Okay, we are going to record the disagreement of the nation of Botswana.” There’s nothing to hold them to. What’s going on in space now is that in order to demonstrate the validity of the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, NASA has paid a private company to recover some lunar regolith, which is to say rocky stuff, and transport it from one place on the moon to another. It paid the company $1 to do that, and what it’s effectively doing is establishing international precedent and the legality of extracting, paying for, and delivering space resources. We’re looking at the opening of a new economy on the moon, and eventually in the asteroid belt and perhaps on Mars. The gold rush has moved up and out beyond Earth.

Robinson

In the book, you draw attention to something that I had never really thought about before. When we got to the moon, we immediately planted the American flag on it, and you mentioned that it was not actually a foregone conclusion. There was a discussion about planting the United Nations flag to suggest that the moon was the common property of all. There’s something very symbolic about the fact that, instead, we claimed it for America. I don’t know if that’s where things took a wrong turn in the journey to outer space, but certainly that is the direction that things continue to go in, with great power competition, militarization, and privatization of space.

Rubenstein

Right. But in the ‘60s, the rhetoric was that Neil Armstrong was walking, and Americans planting, the flag for all mankind. This was the JFK logic of America beating Russia to the moon on behalf of all humanity—that if humanity was to survive, America had to be first. If it wasn’t, the Soviets would be first and make everybody communists and everyone would die. Therefore, America has to be first for the sake of humanity. This is the same rhetoric that we’re getting right now. The billionaires have to be set free to do whatever they want and to pursue their own untrammeled profit for the sake of humanity. We still need that ideological patina on top of it.

Robinson

Yes. Just as colonialism has to happen for the sake of the colonized, as well as the colonizers.

Rubenstein

That’s exactly right. For the sake of their eternal souls. We’re still worried about the eternal souls of humanity.

Robinson

We do it all because we care so much. We wish we didn’t have to care so much, but we do.

Rubenstein

This is the burden of the extraordinarily wealthy!

Hear the conversation on the Current Affairs podcast. Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.