The Libertarian Case for Abortion

As a libertarian, you should cheer when federal protections expand your rights and choices, and be concerned when they limit them. The latest Supreme Court decision over abortion decreases freedom and choice.

It’s confusing to me that principled conservatives can defend this recent Supreme Court decision. Federal laws are there to protect basic fundamental values while allowing latitude to states to provide more, not less. The founding fathers wanted a federal system to avoid tyranny—not to create carve-outs where tyranny is acceptable on the local level, whether it’s slavery or banning abortions or banning guns. The point was to use the states as laboratories for new ideas and programs—not to inflict old ideas on families who should be entitled to make their own choices.

Leave it to the States?

Conservatives often say we should kick the issues to the states. Let the states decide. But why stop at the state level? If allowing choice on a more individualized level is a good thing, why not let families decide? Individuals decide? Why advocate for policing of intimate behavior at the state level if tyranny is the fear?

Now, some conservatives will say that protecting unborn babies is a legitimate state interest that must also be protected. On its face, this is suspicious. If you think abortion is murder, why would you leave it to the states? You would be pushing for a federal ban on abortion—something that’s is being discussed among social conservatives like Ben Shapiro, who seems eager to impose his own depressing, dry, marital practices on others.

As I also discussed on the show, my only real concern is that the women involved — who apparently require a "bucket and a mop" — get the medical care they require. My doctor wife's differential diagnosis: bacterial vaginosis, yeast infection, or trichomonis.

— Ben Shapiro (@benshapiro) August 10, 2020

The “leave it to states” argument is inconsistent with the moral argument against “baby killing,” and the “federal ban” argument is inconsistent with a libertarian belief in individual freedoms.

Moreover, there are no “babies” in question here. Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the case that followed Roe and the one that is really at issue, protects the absolute right to have an abortion only prior to a fetus’s ability to survive outside of the womb. States can, and have regulated abortions after the point of viability—when a fetus might more accurately be described as something we think of as a “baby.” But despite fearmongering about late-term abortions, this new opinion is about making it possible for states to ban abortion altogether, even early in gestation. It is not, like Roe and Casey, an opinion about protecting a range of choices that individuals in the states can avail themselves of. It is, instead, like Dred Scott, a case that limits liberty rights, and instead allows states to enact tyranny on a state-by-state basis. In Dred Scott, the court protected the state’s right to enslave human beings. In Dobbs, the court is protecting the state’s right to force a woman to give birth even if it kills her.

A Question of Freedom

It’s time, as a country, that we really nail down the difference between positive freedoms and negative freedoms. Freedom to versus freedom from. Freedom from state action? That’s what I want. And what you should be fighting to protect—the right to make medical decisions without the police banging down your door to arrest you, your wife, your daughter, or your physician.

Now, many people have been making comparisons between Dred Scott, Plessy v. Ferguson, and Roe, some in good faith, some bad. Senator John Cornyn went viral in a bad way, with a tweet that some people argued recommended a return to segregation as it compared Dobbs to Brown v. Board.

Now do Plessy vs Ferguson/Brown vs Board of Education. https://t.co/hrUYCcIq8Y

— Senator John Cornyn (@JohnCornyn) June 25, 2022

Now, it’s clear to me that Cornyn was not arguing that Brown v. Board, which overruled Plessy v. Ferguson—and thus outlawed segregation—was bad law. His point was the opposite: that sometimes overruling precedent is a good thing. Indeed, he’s right. So how can you tell the difference, as a freedom-loving libertarian? Well, as a libertarian, you should cheer when federal protections expand your rights and choices, and be concerned when they limit them. Desegregation ended artificial limits on free association, and created more freedom for more people. Those who didn’t want to associate with Black people could make, and continue to make, that choice.

Similarly, Roe meant more freedom of choice for more people. Women who did not want to seek abortions, or who find the practice immoral for religious reasons, could decline abortions after Roe. Roe wasn’t a law forcing any kind of behavior, like Dred Scott was. After those cases were decided, Americans could make their own choices: freedom of association. Medical freedom. This is what is at stake. But conservative politicians have often shown a great deal of inconsistency on that score. Just look at how conservatives have repeatedly intervened when states have decided to allow physician assisted suicide.

That’s because none of this is about states’ rights. It brings me no pleasure to point out that this is about a religious minority’s desire to control the behavior of those who do not subscribe to their spiritual belief. Six of the six justices in the Dobbs majority are Catholic, and though these opinions are scrubbed of doctrine, it’s no accident that they keep deciding cases in a way that’s in line with their own religious beliefs—not the law. And if there’s one thing that is quite clear in the Constitution, it’s that no religion should be established above others.

Now, pointing out a politician’s hypocrisy can be boring and redundant. They’re all hypocrites, Republicans and Democrats alike. But it’s important sometimes to unpack hypocrisy to clearly see what the true motivations are here, and evaluate what side you really want to be on.

The Constitution and Unenumerated Rights

Let’s look at federal level protections.

First, guns. The right to own a gun should not be punted to the states. Why not? Because it is a federally protected constitutional right. No matter what the legislature in any given state believes, the Second Amendment is clear that the right to bear arms is not up to the states. Now, no right is absolute. States may constrain certain rights to protect competing rights and liberty interests, but to do so, they typically must prove the government’s interests are narrowly tailored and that any law that would abridge protected rights achieves a compelling governmental interest. This is the basic framework of constitutional law.

The right to free speech is guaranteed by the First Amendment. So no matter what any particular state legislature might think, no state can abridge speech rights unless, again, there is a compelling government interest in, say, preventing incitements to violence, and the law must be narrowly tailored to meet said interest. There are different tests for commercial speech versus inflammatory speech, but on the whole, even though the Supreme Court has upheld certain time, place, and manner restrictions on protest and the like, the fundamental right is protected.

The rationale for constitutional rights is this: some things are considered to be so important, so fundamental, that the federal government will protect you against intrusion by the state. This is true, in some cases, even if those rights aren’t specifically enumerated in the Constitution. On multiple occasions, the Supreme Court has extended federal protection to rights by reading those rights into the text of existing constitutional amendments.

Now, this is, of course, a fiction of sorts. The Constitution doesn’t mention, and couldn’t begin to conceptualize, many contemporary rights or the world that gave birth to them. Thomas Jefferson couldn’t fathom the “internet” or the various speech concerns that arise therefrom. The founding fathers, writing the Constitution in the late 18th century, could not have considered weapons as powerful as machine guns. They only had musket technology back them. Bullets as we know them weren’t even invented until 1832. But given the difficulty in amending the Constitution, people on both sides of the aisle have accepted the necessity of reading certain rights into the Constitution lest we be governed by the dead hand of founding fathers who, though wise in some respects, lacked the understanding necessary to protect all the interests that exist in today’s world.

Notably, the Constitution did not protect the rights of women or minorities. When Abigail Adams asked John Adams to “remember the Ladies” in drafting the laws, he replied “I cannot help but laugh. … We know better than to repeal our Masculine Systems.” And when the Supreme Court upheld a state law requiring a fugitive enslaved man, Dred Scott, to be returned to his enslaver for a life of bondage, it’s not surprising that there was nothing explicit in the written text of the Constitution to save him. In fact, the only constitutional text that explicitly mentioned Black people “treat[ed] them as persons whom it was morally lawful to deal in as articles of property and to hold as slaves.” And so, in the Dred Scott case, the Supreme Court held that, “Any person descended from Africans, whether slave or free, is not a citizen of the United States, according to the U.S. Constitution,” and thus could claim no freedom.

As you remember from history class, or perhaps you were never taught, this decision escalated tensions between the slave-holding south and the north, because some people believed that despite the text of the Constitution, human beings, even Black ones, have rights that should be protected by the federal government.

In 1863, about six years after the Dred Scott case, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation—an act that was not constitutional and which went directly against the holding of the Supreme Court. It changed the legal status of enslaved Black people from slave to free.

Now, again, the constitution did not explicitly grant rights to Black people, and in fact referenced them only as fractions of human beings for census purposes (we probably wouldn’t even have gotten that much notice if southern states didn’t need to gin up their population numbers to secure more representation in the house. After all, in 1960, Mississippi was 55 percent Black). And yet, despite there being no textual support for it, in the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln claimed constitutional authority:

“I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free…. And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God….”

The Emancipation Proclamation was never challenged in court. We had a war instead. The north won. And the issue of whether it was technically constitutional was sublimated to the moral question of whether it’s right to keep another human being as chattel. And most of us think that’s a good thing.

The right to be free from slavery is probably the most extreme example of a fundamental right not explicit in the Constitution being read into it, but it isn’t the only one.

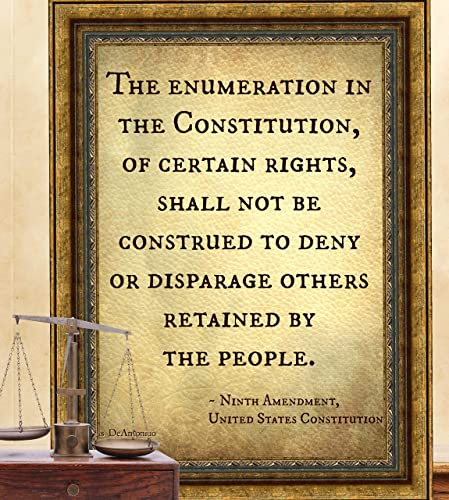

Because the Constitution left so many people out, and because the Founding Fathers failed to predict penicillin, or cars, or bullets, or women’s equality, the Supreme Court has been flexible in using the founding fathers’ words as a guiding principle, but not a strict limit. In fact, the founding fathers anticipated this. They were clear that the Bill of Rights did not constitute a full list of all those rights that were constitutionally protected. The Ninth Amendment makes clear that “the enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” In other words, the bill of rights is a partial list.

In some ways, the Ninth amendment may be the most important. Imagine if the only constitutional rights were those rights that are explicitly enumerated in the Constitution. The state would have an extraordinary amount of authority to regulate your most intimate conduct—well beyond the bounds of what we consider to be freedom.

Consistent with the Ninth amendment, the Supreme Court has found that the right to travel, the right to vote, and the right to keep personal matters private are all constitutionally protected and cannot be abridged by the states—even though they were not specifically enumerated.

The Right to Privacy

Now, in overturning Roe, conservative justices have questioned the right to privacy on which the right to choose was founded. This implicates not just a woman’s right to make medical decisions with her doctor, but also your right to marry who you want regardless of their race or gender. It protects your right to engage in consensual sex acts in your home. It’s the right to be left alone. It is a fundamentally libertarian right that resists intrusions by the government into your home, into your family life, or into your bedroom.

The Supreme Court first established the right to privacy in Griswold v. Connecticut. That case protected the right of married couples to buy contraceptives. Now, to be clear, there’s nothing in the Constitution that prevents states from interfering in a married couple’s ability to do their own family planning. (Based on the text, if California wanted to, say, pass an “anal only” statute, they could.) Citing the Ninth Amendment, which, again, references unenumerated rights, the court defended what most of us understand should be a freedom protected at the national level.

Think about what it would mean if we didn’t have those privacy rights. In Griswold, Connecticut tried to shut down a Planned Parenthood in the state using a 19th century law banning the dissemination of contraceptives. The state arrested Griswold and a medical doctor at the clinic; they were tried in a one day bench trial, and fined. They were literally locked up for handing out condoms.

This is a shocking incursion into private affairs that no state should be entitled to commit. And the Supreme Court agreed, holding that they were dealing with

“a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights—older than our political parties, older than our school system. Marriage is a coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring, and intimate to the degree of being sacred. It is an association that promotes a way of life, not causes; a harmony in living, not political faiths; a bilateral loyalty, not commercial or social projects. Yet it is an association for as noble a purpose as any involved in our prior decisions.”

The choice to get an abortion is a similarly private and sacred association between a doctor and a patient—as is the choice to marry someone of the same sex or of a different race, as Clarence Thomas presumably understands.

And yet in his concurrence, he opens the door to revisiting all the privacy cases except the one that affects his own mixed-race union. But here’s a reminder: the court in Loving v. Virginia protected Thomas’ right to marry his white wife, in part, because it was horrified by the idea that the state should be intruding into bedrooms to uphold anti-miscegenation laws—just as the court in Griswold was horrified at the idea that the state would enter into the marital bedroom to enforce rules around the sexual behavior of husband and wife.

I want to make one more thing clear: I personally don’t think the founding fathers should be followed blindly. They were flawed human beings who did not consider me to be a person with rights under the Constitution—either as a woman or a descendant of slavery. So, I take them and their proclamations with a grain of salt. But that doesn’t mean that certain Enlightenment principles, like non establishment of religion, shouldn’t be deeply treasured. Or, that unenumerated rights should be dismissed just because men of 200 years ago didn’t write them down.

.png?width=352&name=r-cohen%20(1).png)