Alex S. Vitale on Rethinking Policing in The Wake of Uvalde

Revisiting the critique of policing that argues that the police are not equipped to solve social problems or address school shootings. To address harm, we must build supportive institutions.

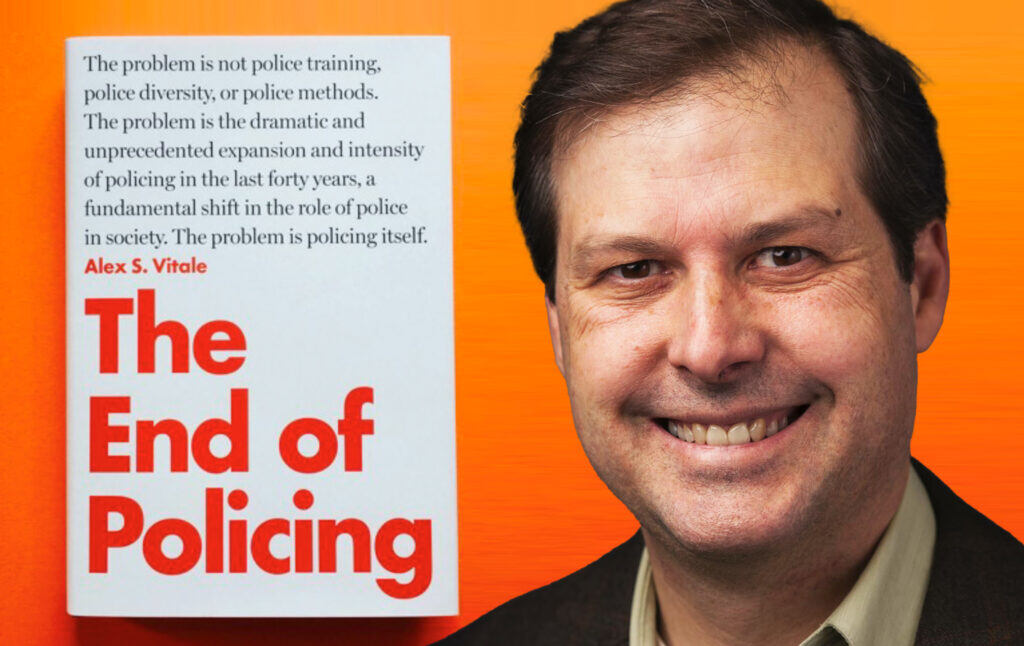

Alex S. Vitale is a professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center, where he coordinates the Policing and Social Justice Project. His book The End of Policing is a comprehensive critique of U.S. police and argues that nearly everything useful done by police can be done better by other institutions. (The book was published in 2017 but recently got an unexpected boost from U.S. senator Ted Cruz.) Prof. Vitale joined editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson on the podcast to discuss how the recent shooting in Uvalde (and the disastrous police response) and the successful recall of San Francisco’s “progressive prosecutor,” Chesa Boudin, should inform our thinking about police and punishment. This interview has been edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

Yes, one of those wonderful things, the anti-endorsement. Senator Ted Cruz held up The End of Policing as one of his examples of the pernicious critical race theory that is infecting our schools.

Vitale

Exactly. He tried to use it as a bludgeon against the Supreme Court nominee at the time.

Robinson

There’s this wonderful photo of him waving the book in the air. Surely it did wonders for sales.

Vitale

I’m sure it did. It totally caught me by surprise. But, more importantly, it gave me a chance to push back against the horrible way that race is framed and has become dominant within the Republican Party. There’s this idea that anyone who complains about racism is a race essentialist, someone who’s just reinforcing the idea of biologically-based race difference. And I took the opportunity in an article in The Nation to point out that, no, racism is a social fact, and it’s a political project of labeling people along race lines for the purposes of political and economic exploitation, essentially. And so to complain about those projects of racial discrimination is not to then necessarily embrace the idea that these are real biological categories.

Robinson

Yes. It’s very bizarre, actually, because they’ve got it entirely backwards, perhaps because they haven’t read any critical race theory or bothered to try to understand it.

It’s also rather interesting to classify The End of Policing as critical race theory. And it says something about the fact that every work that in any way challenges the racial status quo or calls out racism is then lumped into the category of critical race theory. One might very well be surprised to see your academic discussion of policing in America put into the category.

Vitale

It’s kind of a dead giveaway. If you’re critiquing the broken windows theory, for instance, as I do in the book, that somehow that makes you a critical race theorist. And that makes clear their understanding that the project of criminalizing poverty is, in fact, rooted in a racial project.

Robinson

It’s rather an admission. Now, The End of Policing came out in 2017. But, of course, every week in the news, we have something fresh to apply it to. Recently, we had two incidents I want to discuss. The first is the failure of police in the Uvalde school shooting in Texas. We’ve had probably more widespread bipartisan criticism of the police in the last month because of the police’s failure in Uvalde than we have had, perhaps, since the George Floyd protests. And then I also wanted to talk to you about what happened in San Francisco with the recall of progressive prosecutor Chesa Boudin.

First, Uvalde. We had a school shooting, and police have been criticized for basically standing around for an hour before going in to rescue the children. A lot of people expressed surprise that the police would do this. The conversation afterwards was, Well, the police violated their training. These police failed to act according to the standards that we would expect of police. We need more police. We need better police. We need to think about how to improve police responses in school shootings. What does the Uvalde incident tell us about policing?

Vitale

Well, I’m from Texas. I have family not that far from Uvalde. I’ve been to Uvalde. I have school-aged children here in New York. This is really a terrible situation. And there’s no learning happening. This keeps happening over and over again. And we keep being told that the solution is more school policing, more guns in schools, more target hardening. And the lesson, I think, to be learned from Uvalde is that it doesn’t work. Here’s a city that spends 40 percent of its municipal budget on policing. It’s a tiny city with a SWAT team and a school police force. In addition, they had armed guards at the schools. They have a massive Border Patrol substation there with its own SWAT team. They had all the training. Texas has a very highly developed active shooter training protocol, and the officers in Uvalde, including the school police, had taken that training. And there’s so much emphasis on it in Texas because shootings keep happening there. There are so many guns, and they don’t want to discuss gun control. So they keep beefing up policing as the solution, which, of course, just means putting more guns in play.

So then we’re told that we need more training and more guns. It’s like, you’ve done it, it doesn’t work. There were armed school police at Columbine High School in 1999. There were armed police at Parkland High School in Florida when that shooting happened. People have seen too many movies. They think the presence of an armed police officer means that the situation will just be taken care of, that police are perfect shots and perfect decision makers and have superhuman abilities to resist someone shooting at them. And this is all nonsense. This is fantasy and is completely disconnected from the realities of policing, which is that police miss all the time. They shoot innocent bystanders all the time. They are afraid of getting shot, quite reasonably. When confronted with an active shooter, it is terrifying. And it is not clear what to do no matter how much training you’ve had.

Robinson

Now, some of your critics would treat your work as anti-police. But, in fact, one of the things that comes out of what you’re saying here is that the criticism of police in Uvalde is almost unfair to the police because it expects more of them than a police force in a small town would ever be capable of. They would have to become Navy SEALs within five minutes and be ready at any moment in time to swoop in with no mistakes and no confusion. The school district police chief finally started talking to the press and he started justifying what he did. You could say it’s an excuse. But all of his explanations—why they couldn’t get the armor and why they couldn’t get into the door—are very human, even if they sound like disastrous mistakes. The human element is going to be very, very difficult to fix. So if you’re relying on police, you’re relying on human beings. The institution of policing might not be up to the task.

Vitale

Well, let’s not overstate the effectiveness of Navy SEALs. They make a lot of mistakes, too, and are not some perfect tool for solving our foreign diplomacy problems. I’m glad you pointed out, though, the larger truth, which I think is reflected in the book, which is that this is not an attack on individual police officers. I have worked with police all over the world for decades. I have many friendships with police around the world. This is not about attacking their individual motives or making it out to be just about really bad people. No. This is about a set of political institutional mistakes, of thinking that police are the solution to school shootings, to mass homelessness, to our nation’s awful drug problems, and to childhood poverty. It’s just a political mistake.

The police didn’t create the war on drugs. The police did not systematically defund mental health services. The police did not under fund schools. They have been tasked with trying to pick up the pieces of a set of political decisions that have been deeply harmful to American society. And so, my goal is to go over the head of the police and to move from police accountability to political accountability, if you will.

Robinson

I’m certain that the police who responded in Texas are going to live forever with the feeling of guilt that they didn’t save those children. And a lot of people are going to blame them for the deaths of those children. We had Rosa Brooks on the program; she has written a book about her time as a police officer in Washington, D.C. She’s probably more sympathetic to the police than I am. But she says something that I think that you say, as well, which is that police are asked to solve problems that they cannot solve. And the training gives them the tool of arrest. And that is the tool that they can use to deal with all of the reasons that people use 911. They are being asked to do something they are not capable of doing and that they have not been trained to do. And the results are kind of disastrous.

Vitale

This is actually a good transition to talking about the Chesa Boudin. So let me just say that we just had a research article come out that was profiled in Scientific American and several other places about the STAR program in Denver. Now this is a program that was developed before the George Floyd uprising, but has only been implemented in the last year or so. And it’s a non-police crisis response team that responds to 911 calls around a mental health crisis, such as a homeless person in distress or someone having a challenge related to drug use possibly. And what they’re finding from these programs is, not only is it a better way of dealing with someone in crisis, so that it reduces the likelihood of violence and arrest, but what they found in Denver is that it’s reducing crime broadly. Because what happens is that someone who’s having a mental health crisis is also maybe engaged over time in some shoplifting or disorderly behavior, some low-level assaults or threatening behavior. And by sending someone other than police and utilizing a tool other than arrest, they’re actually helping to resolve these people’s problems and preventing a whole set of future illegal harmful behavior.

And the reason this connects with the Chesa Boudin situation is that the right-wing narrative that helped unseat him says that, Well, there’s crime and disorder in San Francisco and the solution is to be more aggressive about locking people up. But when we look carefully, what we see is that these people have been locked up many times, and then released and then locked up and released for very minor offenses. For the most part, these are not serial killers; these are homeless people with mental health and substance abuse problems. And that system of locking them up, arresting and policing them, does nothing to fix their situation. But here’s the tricky part, here’s the converse of it, which is that decarceration alone is not really a solution either. And this is the limit to a kind of progressive prosecution strategy in my mind. This has always been a limit of it that I’ve tried to point out, which is that it’s not enough to just keep these people out of jail, however just that is.

We have got to create community-based infrastructures that allow people to live independently without imposing all kinds of harm on communities. And so while Chesa was incredibly successful at reducing the number of people being jailed and imprisoned, which I support, he, in his job, is not in a position to create these new community infrastructures. Larry Krasner, in Philadelphia, faces the same challenge. But he’s been using his bully pulpit, if you will, to try to pressure the Philadelphia city government to create more of those infrastructures so that there is a choice other than jail or nothing. And I think that’s really essential here.

Robinson

The narrative around the successful recall of Chesa Boudin in San Francisco is that he was soft on crime and the voters of San Francisco were frustrated with his sympathy for criminals and therefore threw him out of office.

Krasner is a very interesting comparative study. He was reelected rather than thrown out of office. There’s an article in Slate by John Pfaff recently, pointing out that Krasner’s base of support is, in fact, in the neighborhoods with the highest violence, such as in communities of color. And that, in fact, the progressive prosecution model has often been most favored in the places that are most victimized by violent crime. But as you point out, that is, in part, because it has to be coupled with a vision not just for scaling back the carceral state but reinvestment as well. One of the complaints of places that are subject to the greatest violence—such as communities of color—is that they are simultaneously over policed and under policed or that they have too much aggressive policing and are also neglected. They have a simultaneous authoritarianism and austerity at the same time.

Vitale

That’s really the way to frame it. The under policing/over policing framing is really problematic because it implies that if the police just targeted the right offenses in the right way, then we would have better outcomes. But there’s actually not really much evidence to suggest that this is the case. Logically speaking, it doesn’t work. Let’s say a community is experiencing an uptick in street violence—as opposed to domestic violence or armed robberies of businesses or something. The way the police handle those is not through complex forensic investigations like what you see on television. What they do is they go out and they make lots of low level arrests. And they use that to try to pressure people to give up information. Who’s got the guns? Who was behind that shooting? Which gang is angry at this gang? Who’s got the beef, right? And they do low level gun interdiction, which is essentially stop and frisk. They just stop every person targeted in a certain demographic in a community in hopes of getting some guns off the street. Well, none of that works. And it is exactly an example of the over policing that people are complaining about.

So this idea that, Well, if they just focused on homicides and got their clearance rates up, that this would be what protects the community. But the way policing tries to get the clearance rates up is through huge numbers of stop-and-frisk stops, and lots of low level arrests, so that you can’t use policing to get out of this under policing/over policing. So framing it as both austerity and intensive/aggressive policing, I think, is exactly the right way to frame it. These communities have been defunded by both the private sector and the public sector. And—surprise, surprise—that produces criminal behavior, it produces black market activity, it produces interpersonal beefs that escalate. It encourages gun carrying for defensive purposes. And then this is met with intensive criminalization, which doesn’t actually fix the problem.

So we have to decenter this idea that policing and incarceration are the only possible tools available to deal with the problems these communities face. And I think that idea is actually getting through. I think, increasingly, what we’re hearing in high crime and disorder communities, is that they want something other than policing to fix their problems. They want community-based anti-violence programs, they want non-police, mental health crisis teams, they want drug treatment on demand, they want harm reduction services, and they want jobs for their young people. And so if we can reach a point where the choice is no longer between police and corrections or nothing, where the choice is between police and opening up a new youth recreation center with trauma counseling and job preparation, then all of a sudden, we have a whole different set of political choices available.

Robinson

The critics of policing and prisons have not managed to successfully get past the criticism or perception that what we are offering as an alternative to policing is nothing. The idea is that you’re going to defund police but not fund anything else. That’s the way it’s framed, right? So the focus is on the defunding and not on the other thing that you’re going to do instead. In advance of this interview, I was reading a critique of your book by Matthew Yglesias in Vox. And one of the things he says is that there’s a correlation between more policing and less crime. And if you take away the police, you get more crime. And if you add police, you get less crime. But that way of thinking suggests that we have one dial and that dial is cops. We could turn up the cops dial, and we can turn down the cops dial, and we can see what that does. The assumption is that we don’t have any other dials. So we are offering people either the police or nothing. And the argument is that if you take away the police, you will get anarchy. So perhaps you could respond to that.

Vitale

Well, in your own publication, Alec Karakatsanis, in 2018, wrote a wonderful retort to the Yglesias review of the book. People should read it. There are a couple of fundamental flaws in the Yglesias article and a kind of willful misreading of my book. Actually, there’s a lot of really interesting stuff that I agree with. And then he spends 90 percent of the review critiquing something that isn’t even in the book and that is not a representation of what’s actually in the book, but a sort of indirect critique of the whole movement. So here’s the situation. The studies that he’s talking about don’t really say what he says they say, and the evidence behind them is very thin. And the vast majority of studies don’t show this. So he’s cherry picked a few really weak studies to make very strong claims in a way that’s intellectually dishonest. And Alec and others like Naomi Murakawa have pointed this out to him, and he refuses to address it. Second, what these studies fail to do and what people like Yglesias and Thomas Abt and other defenders of policing fail to do is to measure costs.

So they assume, as you pointed out, that there’s one tool available policing, and we can dial it up or dial it back. And if policing saves one life, then we’ve proven that it works. And we should just do as much of it as we can. But what if in the process of allegedly saving one life, police kill three people or destroy a community? They make tens of thousands of people unemployable? They enact terror on whole neighborhoods? And they bankrupt city governments so that there’s no money available to provide basic educational services, mental health, drug treatment, jobs supports, family supports? So they will sometimes do this really superficial cost analysis. What they do is say, well, 50 police officers cost this amount of money. And then they’ll say it showed that they saved three lives. And then they have an insurance adjuster claim that each life is worth $5 million. And so, therefore, the policing intervention costs $6 million, but the saved lives were worth $10 million, and therefore it’s cost effective. But, of course, the $10 million is a completely made up number. It doesn’t feed into anything. It’s just made up. But the real cost in terms of lost lives and destroyed communities never gets factored into these discussions, nor does the fact that there are other interventions available that cost less and that also have proven effectiveness, and that would save many more lives.

Robinson

Let’s think about an example of the logic that you’re using here. In the case of school shootings, there is one way of looking at the Uvalde school today that says, Well, the police went in and saved x number of lives, which is the number of children who successfully were saved from the classroom and from the school. Therefore, we can see that the police saved lives. But what we are not doing here is thinking about the alternatives and the costs. How much did the police cost? Or, were there other ways to achieve far more saved lives? So the police will take credit for every child that was saved in that school and say, Well, look, if we have not been there, in the absence of us, the shooter never would have been stopped. And that might in fact be true. But what we are not thinking about is the question of whether beefing up police at every school is the most cost effective thing. And is it, in fact, the way to maximize the number of lives we are saving? And when we actually look at what happened in that situation and we think about what the alternatives might be, we actually see that we’re deploying an incredibly unreasonable and cost ineffective way to maximize the number of children’s lives saved.

Vitale

Yes. As horrible as they are, school shootings are fairly rare occurrences, and the risk of a child being killed at school is much less than the risk of being killed at home, actually. But the Right uses the school shootings as a justification for building an entire infrastructure of school policing that 99.9 percent of the time is not used for that purpose. It’s mostly used for searching kids for drugs and harassing them with metal detectors and arresting them for being disruptive in class, and so forth, with huge impacts on student well-being and huge negative impacts. The research is completely unambiguous here. School policing is a horrible idea that does not keep kids safe. And it was created mostly to instill a kind of loyalty to policing and ‘law and order’ politics and to teach kids respect for authority (this has been the real motive) and as coverup for austerity and so forth. So, in addition, for the claim that school policing is effective at protecting kids from school shootings, the evidence is just not there. It’s not effective. And then, as you point out, where’s the real measurement of costs, the real cost of school policing—on children and on communities—and then where’s the discussion of alternatives?

And, of course, the whole conversation has been perverted by the gun lobby because it’s essential that we not talk about prevention because prevention would inevitably lead to a discussion about the availability of guns, which, of course, is completely politically off limits for them. I would be happy to have all kinds of gun control measures pursued, such as assault weapons bans and raising the age of purchase and limits on high-volume magazines. I’m in favor of all that. But I think we can’t limit the conversation to that. We’ve got some difficult political hurdles to overcome in that arena. And also, those gun control measures are not the full solution. We’ve got to understand what’s driving this desire to lash out in this most harmful way. And the FBI did a systematic study of school shootings. And they found that in 90 percent of cases, there were people who knew ahead of time and they either did nothing, because they do not want to turn someone into police on a suspicion—who wants to be the kid in high school who turns some kid into the police? No one wants to do that. And in some cases, the police were notified. But the police are like, Well, no one’s been shot yet. So there’s nothing we can do.

So we need early intervention systems that aren’t rooted in the criminal legal system and that are tied to school counselors and that are tied to mental health facilities and that actually help young people. We need to address the culture of bullying and violence that is widespread in schools in America. Racial discrimination, discrimination of LGBTQ kids and non gender-conforming kids—we see that this is what drives a lot of this horrible lashing out. The shooter in Uvalde was experiencing intensive bullying over a long period of time where nothing was done. And people knew the kid was involved in self-harming behavior and glorifying guns. Kids were afraid of him. Kids knew this was in the works. But they didn’t know what to do about it.

Robinson

That’s really interesting and highlights the brutality of police and the failure of policing as an institution to be able to deal with people like that. But it’s your only option. When you said that no one wants to call the police, it’s true because you know what police do. When you call the police, often with someone who’s just kind of menacing and scary, they’ll tell you, Well, there’s nothing we can do about this because this person has not committed a crime, which is true, because there is nothing they can do about it. It’s not how the institution is designed. And then, secondly, there is the fact that throwing someone into the criminal punishment system is a horrible thing to do to them if they haven’t actually hurt anyone yet. And if that is your only option, then you really have no options beyond something that is clearly an overreaction. That doesn’t help.

Vitale

Yes. A lot of schools have created these zero tolerance programs where if a 12-year-old is doodling a little war scene with guns in their notebook, that’s considered an example of gun violence, and then they get suspended. So there’s this overarching idea of a punitive social control system that is completely misunderstanding the minds of children and is not catching the real problem because it’s all focused on control and these outward signs. And the other thing I want to say is that creating real infrastructures of counseling support and mental health services would not only help prevent school shootings, it would help prevent the more pervasive problems of youth suicide and youth overdoses—both of which we do very little about and which take many more lives than school shootings do.

Robinson

The Right loves to talk about cost-benefit analysis. It’s their favorite way of analyzing what to do about anything. But what you pointed out is that when it comes to police, we really don’t actually conduct a cost-benefit analysis. We really don’t think, What are the costs of approaching any given social problem through policing? We only look at the good side of what police do, which is marginally bumping down the crime wave, supposedly. And we don’t think about what the other paths to achieving this outcome are.

Vitale

In the current world that we live in, the existence of a policing infrastructure provides some broad protective benefits to society. Obviously, if all police disappeared tomorrow, there would be hugely negative consequences from that. But, of course, that’s not what anyone who’s really involved in organizing around these issues is calling for. First of all, it’s ridiculous. There’s no magic switch that we could just turn to make the police disappear. There’s no city that’s going to eliminate its police force because we had a protest outside. What people are calling for is interrogating specific decisions being made right now, influenced by an analysis that says, you know, policing doesn’t work as well as we think it does. It comes with huge costs, we have better alternatives, and we should guide our decisions based on that analysis.

So in the wake of Uvalde, should we be spending more money on more school police? Or should we begin to hire counselors to create mental health services? The answer seems pretty obvious to me, especially when we use that analysis. Should we be spending more money on gun interdiction units that are notoriously corrupt and brutal and ineffective? Or should we be investing in community based anti-violence initiatives that are showing tremendously positive results without throwing people’s lives away or criminalizing whole communities?

Robinson

For those of us who are critical of policing and of mass incarceration, I wish we could be more successful at conveying the message that we, in fact, are stronger opponents of violent crime in that we want to see fewer people being victimized in murders and robberies and rapes. But we are trying to adopt a sensible approach to making sure that those things do not happen in the first place by thinking about why they happen. And there is this very, very successful attempt to portray progressives and portray critics of police as not caring about those things, when in fact, the opposite is true. We want to create a society in which people are safe, and we are horrified by this disastrously inefficient and cruel punishment system that has arisen as a pseudo solution to these problems.

Vitale

Yes. I think anyone who questions that should start by reading Derecka Purnell’s book Becoming Abolitionists. She’s someone who grew up experiencing crime and violence and victimization and for whom police just weren’t the solution. Look at Beth Richie’s work about the failures of policing to keep Black women safe, whether it’s domestic violence or in the community. We need to hear the voices of folks in these communities who experience violence, both from people they know and from the police, who are increasingly clear about the need for strategies other than policing to keep them safe.

Robinson

Let’s go back to San Francisco. What does worry me is this narrative about the lawlessness enabled by reformers and the fact that it succeeded in ousting Chesa Boudin. He was, in some ways, a little bit doomed by the fact that he had a limited number of tools available to him. And without progressive governance in the rest of the city, you can’t really fit what you’re doing as a prosecutor into the wider reform model. What would you do if you had to talk to one of these San Francisco voters who was worried about violence and had voted for the recall? What would you say to them to try to change their perspective or get them to think a little bit differently about the issues here?

Vitale

I lived in San Francisco for a number of years in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. I worked at the San Francisco Coalition on Homelessness, and I wrote a dissertation that was in part about the rise of quality of life politics in San Francisco in the ‘80s and ‘90s. San Francisco, in response to the first wave of criminalizing homelessness, elected the chief of police mayor on a ‘round up the homeless people’ platform. So this is nothing new.

While San Francisco is reliably democratic in national elections, at the local level, they’re deeply committed to a kind of global cities model of economic development, which means neoliberal subsidies to high finance to big downtown real estate deals to the high tech sectors, and abandonment of the poor. A lot of lip service, a few targeted social services programs, but 75 percent of the homeless population in San Francisco today was born in San Francisco. These are not people from other places. This is a myth. But San Francisco has no plan to do anything about it.

They do not have any plan to invest in the kind of social housing with support services that would be necessary to address homelessness. And the voters who voted out Boudin were not voting because they were personally afraid of violent victimization in their everyday life, because the folks in those communities voted for Boudin. Just like that same dynamic you mentioned with Krasner in Philadelphia. It was wealthier, whiter communities in the outer parts of the city who don’t like the disorder. And that’s different.

They don’t like the fact that there are homeless people living in the center parts of the city and increasingly in the outer neighborhoods. They don’t like the disorder of the Tenderloin and Market Street when they have to go shopping or access government services. They find it unsightly and unsettling. And they also don’t want to do anything about it that would impact their real estate values, their livelihood, their tax rates, and so forth. And so this is a fundamental contradiction with this kind of Democratic neoliberal politics of austerity, which is that they want liberal tolerance in theory, as long as it doesn’t affect their pocketbook or quality of life. And when it does, they will vote for repression.

Robinson

When they see homeless people, then they call the cops?

Vitale

Yes, they are Karens.

Robinson

It’s a real type of person.

Vitale

And it’s not because I think we should have homeless people sleeping on every street corner. I mean, I have spent my career trying to get cities to invest in supportive housing. I’ve written parts of two books about this. I’ve spent part of my career actively saying, No, the solution is to actually invest in social housing. But this is so contrary to the dominant neoliberal framework that is at the heart of Democratic Party politics that they have no intention of doing that. So they need policing to come in and fix a problem for them.

Robinson

You have no magic solution. You either have to house people or you have to accept that you are going to have a lot of homelessness on your street or you are going to have to have a dystopia of aggressive policing in which homeless people are hauled away to jail. They said these are three options.

Vitale

Exactly.