The Holocaust and Cary Grant

On the pain and horror concealed beneath cheerful images.

Content warning: violence, abuse, ethnic slurs

For many years, the United States had no museum focused on slavery. The one major effort to create an official national slavery museum “collapsed amid a welter of debt and recriminations.” Finally, in 2014, a former plantation in Louisiana—the Whitney—was opened to the public as a museum and memorial focused on slavery. This largely occurred because a single wealthy lawyer made it his personal mission to remodel the site and present the ugly facts of slavery directly. Other plantations have buried their history; the houses are the sites of weddings and parties, and at many there is little indication that a colossal crime against humanity took place there. The slave cabins are long gone and the main house is presented only as a unique exemplar of antebellum luxury. Louisiana’s Greenwood Plantation, for instance, touts itself as a “truly magical and majestic place” that is “the perfect location for events and meetings,” promising “majestic oak trees framing your [wedding] ceremony.” Unmentioned in the promotional literature is the fact that for the first part of its life this magical home was the center of 12,000 acres of sugarcane production worked by several hundred enslaved human beings.

The Whitney Plantation’s approach makes for a very different experience. It is not magical to visit. It is traumatic and sad and painful. It also demonstrates the ways in which important historical truths have been obscured. On my visit, I was struck by the fact that the main house only looked like a sumptuous wedding cake from the front, the public-facing side visible from the Mississippi River. At the back, it looked like what it was: a forced-labor camp. It was spartan and ugly. The house’s facade was just that, a decorative cover. When restored accurately, the house was very obviously the headquarters of a sugarcane operation farmed by the enslaved, rather than a place of peace beneath the oaks. The original “magical” Greenwood plantation, on the other hand, burned to the ground in 1960, and was reconstructed in the romantic image of what the owner thought the Old South must have been like. (Its website explains that it has since become a “favorite of Hollywood” and featured in such films as GI Joe II and Jeepers Creepers III.)

It is an easy thing to cover up a historical atrocity. After all, every new generation has to be educated anew; nobody is born with a knowledge of what came before. At the Whitney, there’s a map showing all of the sites in downtown New Orleans that once contained the offices of slave traders. There were at least a dozen along the short route I take from my home to the office. I had had no idea there were so many. And if that one lawyer hadn’t decided to spend his wealth building a slavery museum, I probably would never have known just how ubiquitous these dealers in human beings had been in my own neighborhood.

I think a lot about images and realities, how things look from one perspective versus how they really are. An actor or politician who seems affable and self-deprecating in interviews, and has a winning public persona, can be a total monster to their subordinates when the cameras are off. The look of a delicious bacon strip helps us forget that a sentient creature suffered horribly so that we could eat it. A country can appear free when you walk down the street, but have millions of people locked away in jails and prisons which are kept far out of view. Nations think other nations are mysterious, sinister Others when in reality, human lives are extremely similar across the globe. Many people in the United States sincerely believed their country was nobly fighting to help the people of Vietnam and Iraq, while the reality was death and mayhem in the service of nothing except U.S. power.

And of course, there’s Cary Grant.

“Do you know what’s wrong with you?… Nothing.” — Audrey Hepburn to Cary Grant in Charade (1963)

There was no such person as Cary Grant. That’s not my opinion, that’s Cary Grant’s opinion. Grant began life as Archie Leach, born to a poor family in Britain, and in his own view, Archie Leach was what he remained. Grant said that if someone shouted “Cary” in the street, he wouldn’t notice, but if they said “Archie” he looked around. Cary Grant, the definition of the debonair romantic lead during Hollywood’s Golden Age, thought of “Cary Grant” only as a persona:

“He’s a completely made-up character and I’m playing a part. It’s a part I’ve been playing a long time, but no way am I really Cary Grant. A friend told me once, ‘I always wanted to be Cary Grant.’ And I said, ‘So did I.’ In my mind’s eye, I’m just a vaudevillian named Archie Leach… Cary Grant has done wonders for my life and I always want to give him his due.”

Eventually, after therapeutically taking LSD a hundred times—an experience he found life-changing—Grant would feel that Archie and Cary had finally been united into one man, in whose skin he could feel comfortable. But that came after decades of anxiety over who he “really” was and how it related to the pictures of him on screen.

Knowing Cary Grant only through his screen appearances, it is difficult to imagine this. During his years as Hollywood’s leading leading man, the typical Cary Grant character was a gentleman of style, wit, and poise. There is, as Hepburn’s character said in Charade, nothing wrong with him. Perhaps he sometimes seems a trifle arrogant, and in Suspicion (1941) his wife thinks he might be trying to poison her—but it turns out to be just an unfortunate misunderstanding. Perfectly attired, perfectly charming—and yet the real Grant was an anxiety-ridden acid head who destroyed marriage after marriage (four in total). The truth is difficult to visualize because the illusion was so practiced. (The best biography of Grant is called A Brilliant Disguise, and it was.)

It is so easy to be fooled into thinking things are other than they actually are, because each individual person has access to only a tiny sliver of information about the world. Everything I know about China, for instance, has been mediated, because it comes to me through media (I have never been there). At best, this means seeing something through a glass, darkly and with a smudge. At worst, when some interested party controls access to the informational slivers we receive, our perception can depart entirely from the reality. This is why public figures can very effectively trick us into thinking they’re nice people when they’re not: they determine which parts of themselves they show and which parts they conceal, and we can only guess what they’re like by extrapolating from the parts we are shown. Harvey Weinstein was a different person to different audiences. To Hillary Clinton, he was a perfect gentleman. To women he had power over, he was hideously abusive. Plenty who knew him said they never had any idea how bad his conduct was, and it’s not surprising. The worst people carefully manipulate the perceptions of others.

Serial killer Ted Bundy, one of the most depraved people to ever live, projected the image of a promising All-American young gentleman while secretly engaged in murder and necrophilia. True crime writer Ann Rule, in a fascinating book called The Stranger Beside Me, writes of her own interactions with Bundy and the difficulty she had in grasping the gap between the person she knew and the person who murdered 30 women. Before his convictions, Rule had worked next to Bundy at—of all things—a suicide hotline, and found him to be “kind, solicitous, and empathetic.” It took Rule years to accept that her friendly colleague Ted was actually a monster. He had carefully selected what parts of him Rule would see, and the image seemed so real that it took a mountain of evidence to grasp that it wasn’t.

I have in my office a fascinating old magazine, a copy of Fortune from July 1934. It’s a special edition devoted to profiling Mussolini’s Italy, and the editors of Fortune liked what they saw. Every page is full of tributes to the effectiveness of fascism at building roads and fostering a sense of national solidarity:

It is perhaps Mussolini’s greatest triumph that he has made the Italians realize that if they are to get anywhere among the really Great Powers… their only chance to do so is through the sacrifice of a great disciplined effort. And not only made them realize it but made them act on it to the extent of making, more or less willingly, daily sacrifices to the State. That stern spirit is the spirit of Fascism, and it may well cause the observer to remove from the Italian people the degrading label of ‘wop’ and substitute instead the accolade of ‘Roman.’ Civis Romanus sum!

Fortune’s appalling assessment of Fascism was that “the wops are unwopping themselves.” It even praised Mussolini’s railroad management: “Signor Mussolini did make the trains run on time. He is making them run faster. Much more successfully than the French, he keeps them on the rails… the unwopped trains are now drawn by modern, efficient and most unwoppish electric locomotives.” While Fortune insisted that as journalists they were “by definition non-Fascist,” nevertheless “the good journalist must recognize in Fascism certain ancient virtues of the race.”

Awkwardly, shortly after the special Fortune issue came out, the Italian regime began “burn[ing], slaughter[ing], dismember[ing], gass[ing], and put[ting] in concentration camps large numbers of Ethiopians as part of its occupation of that country. There is evidence that the deaths were in the millions. One-tenth of the population of Libya would die during Italy’s occupation of it, and “from May 1930 to September 1930 more than 80,000 Libyans were forced to leave their land and live in concentration camps.”

Americans in the mid-1930s would not have any idea of the true nature of Italian fascism. The information coming to them from their press simply excluded the regime’s crimes. Even Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to Mussolini as “that admirable Italian gentleman.” My 1934 copy of Fortune is a giant lie, but an effective one. It’s gorgeously produced, and if it was literally all you knew of fascist Italy, it would be hard not to come away sympathetic.

It’s unsurprising that businessmen who read Fortune might be inclined toward fascism, though it’s striking to see the editors so openly warm towards it. But there’s something disturbing even about the innocent and delightful films of the Golden Age Of Hollywood. They present a grand illusion of normalcy in a way that is disturbing and perverse. The more time I have devoted to studying and trying to understand the Holocaust, the more eerie I have found the films of Cary Grant. When The Philadelphia Story was released in 1941, the crematoria of Auschwitz were at full capacity, and the greatest crime in modern history was unfolding on the other side of the ocean. The films of the time are part of the general climate of denial and distraction, Hollywood presenting audiences with a kind of strange alternate world for them to mentally inhabit, one where stories make sense and nothing too terrible ever happens. While Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn were bantering on screen, fascists in Europe were committing acts so vile and twisted that just to think about them for too long, or too vividly, can disturb you for days.

It’s very difficult to confront or even convey the truth about the worst things in the world. Hiroshima, atrocity, death, mayhem, brutality, carnage—these are not only words, but they are soft words. They do not touch the dark thing that is the truth, because nobody wants to go near that. An actual atrocity is so much worse to witness or experience than the words used to describe it can ever convey. And if we did try to convey it with words, we might turn people off—our words might be called too “graphic” or “morbid” or “gruesome” or “lurid.” Thus those of us who want to try to prevent suffering are stuck, since it is impossible to actually describe or depict the worst kinds of human suffering in ways that come close to capturing its nature without making someone so queasy that they don’t want to hear another word.

Get too close to empathizing fully with suffering, and you may find yourself in terrible agony. The closer I get to understanding the truth of what the Holocaust was for the people who lived it, or what war is for those who see it up close, the more I have to back away and run, for the good of my own peace of mind. Occasionally in reading about war, I will run across some particularly horrible crime mentioned briefly in a list—bayoneting children, for instance. And I will have to not think about what those words really mean. Because if I look at an actual child, and think about what a child is like, and what a parent feels for a child, and the pain of the child and the trauma of witnesses—if I start to penetrate the words to get to the truth—I will hurt myself. I cannot bear it. The nearer you get to seeing what dark things humanity is capable of, and understanding them as real-world happenings rather than words in a newspaper, the more you empathize, the closer you are getting to feeling the worst feelings that can ever be felt, feelings that may make it hard to keep living or to come back to happiness.

I once wrote an article about nuclear weapons, and it was intended to convince people of just how horrific nuclear weapons are. I tried to get people to think of what it meant for an entire city to be destroyed instantly. But I didn’t really try to get them to think about it. I left out the parts that would make them throw up. I took them to the very outermost edge of the darkness, and I tried to have them touch it, enough perhaps to where they would talk a bit more about nuclear arms control. But you cannot go too near the darkness, or it will swallow you whole. Even with such a toned-down article, I got an email from a distressed reader who had been having nightmares about nuclear catastrophe since reading it. I took them too near, and it induced terror and paralysis. They thought too hard. You can’t think too hard. It will destroy you. It is a black hole, and if you cross the event horizon, you will never escape.

“Think that’s about the Holocaust? That was about success, wasn’t it? The Holocaust is about 6 million people who get killed. Schindler’s List is about 600 who don’t.” — Stanley Kubrick on Schindler’s List

Kubrick was noting make a Hollywood movie “about the Holocaust,” but you cannot make one that is actually about the Holocaust, because in the real-world event, the kinds of stories of triumph and survival that make for compelling films were the exception rather than the rule. At the end of Roman Polanski’s The Pianist, nominated for seven Oscars (and winning three), the main character, Władysław Szpilman, having survived the Warsaw Ghetto and narrowly avoided extermination at Treblinka, plays Chopin’s “Grand Polonaise brillante” for an audience after the war. It’s a true story, but one with a comparatively positive ending, just as with Schindler’s List and Life Is Beautiful. To show the true events would be impossible, because it would consist of hours upon hours of people being killed pointlessly in horrible ways. You would show a life, get to know a person, and then see that life snuffed out. And all the lives around it. Over and over again millions of times. Hollywood requires moderated tragedy rather than meaningless misery and trauma.

I am telling you this because you should know that, as a writer, I am unable to completely tell you the truth about things. Whether writing about factory farming or war, I have to use the terms that convey just as much information as will hopefully stir you without giving you the full picture. I cannot take you across the event horizon, because I need you to have hope and energy to go out and do good in the world, rather than just be despondent and disturbed. But I need you to know and remember that there is much more we are not confronting. When CNN reports that several people have been killed in an airstrike, and shows a woman crying over the loss of her child, they are showing you only the information that will not disturb you. They are not showing you what a child looks like after being killed in an airstrike, and they cannot take you inside the pain of a mother who sees it. If you saw it and felt it, perhaps you would hate your government more, and be less likely to accept “bombing the Middle East” as something U.S. presidents do as a matter of course. Or perhaps to keep from being sucked into the black hole of despair, everyone would quickly become desensitized. I do not know. All I know is that there is far more, and far worse, than is seen on the surface, and that it matters. As I write, Boris Johnson is planning to significantly expand the U.K.’s nuclear arsenal. Nuclear arsenal. Just words. But if that arsenal is ever used, the consequences… well, all I can give you are more words. Unthinkable. Indescribable. Catastrophic. These, however, do not touch the reality of how bad it would be.

I do not mean to be depressing. I really don’t. Yet if we are to mobilize people to stop suffering, perhaps we must take ourselves ever so slightly closer to the edge of the black hole to remember what it is we’re talking about stopping. Personally, I have found that reading first-person testimonies from the Holocaust fuels my determination to do my part to make sure nothing like it ever happens again. It’s concerning to see that younger generations have a very limited knowledge of the Holocaust, struggling just to remember the basic historical facts, let alone to appreciate what it actually meant for both those who died and those who survived. We must understand what happened so that we know why it was so atrocious that the New York Times buried Holocaust stories in the back of the paper, and why it is so atrocious that crimes against humanity (there, another term that doesn’t even begin to convey its meaning) can still occur, all the time, without anybody caring.

It’s not that Cary Grant shouldn’t have made movies while the Holocaust was happening. Everyone needs relief during the worst times. But we must confront the way that the United States was indifferent to the suffering of a population—European Jews—whose lives simply did not mean anything to most Americans. The country’s population was encouraged to dwell in a fantasy America of the mind.

We still are. If you visit the national World War II Museum in New Orleans, you’ll see what I mean. The museum is big and beautiful—and has almost nothing to do with World War II. Visitors get to see original planes and tanks, and walk through a replica of a German forest, and look at the equipment soldiers carried. They get to watch a “4D” film about the war narrated by Tom Hanks—4D because props pop out of the floor. Afterwards, you can visit a replica of a 1940s ice cream parlor to have a milkshake as “In The Mood” by Glenn Miller plays. Then you can pick up souvenirs in the gift shop.

The museum doesn’t take people close to the darkness that is the real-world experience of war. It doesn’t want to ruin people’s vacations with, you know, the actual things that happened. You leave the museum with a slight melancholy, if that. If you like, you can just look at the big planes and stuff.

The Whitney plantation did something different to me. It was purged of idiotic nostalgia. It does not try to make you feel okay. It takes you closer to the darkness than you wanted to go (but still not too far). The tour guide had us touch the sugar cane, and I realized I’d never touched sugar cane before. I couldn’t believe how rough it was: it felt like the leaves were covered in tiny razors. I began to think about what it must have felt like for enslaved people to have to work with this stuff in the scorching Louisiana heat. An abstract “crime against humanity” felt ever so slightly more real. The Whitney plantation experience, and experiences like it, should be mandatory.

When I look at Cary Grant, I see the Holocaust. Not always. Sometimes I just see His Girl Friday and I enjoy it. But I am aware that what I am watching was created within a context of a crime. The “dream factory” of Hollywood kept people indifferent to the worst things imaginable. Not every film was set in an alternate universe where the war was not occurring—there are movies like Casablanca in which the threat of being sent to a concentration camp is quite real. But even in these films, the pure evil of Nazism was never on display in its entirety, and Humphrey Bogart was never going to be executed pointlessly in the first five minutes, as may have happened to Rick Blaine’s real-world counterpart.

The world has beautiful things in it. Some things are so beautiful that you can’t even believe they exist—leaves, stars, babies, etc. I am constantly amazed by humanity’s positive achievements, by giant cathedrals and Skype and live recordings of Prince. It can be difficult to reconcile just how good the good things are with just how bad the bad things are. How can nuclear weapons coexist with flowers or sex or North by Northwest?

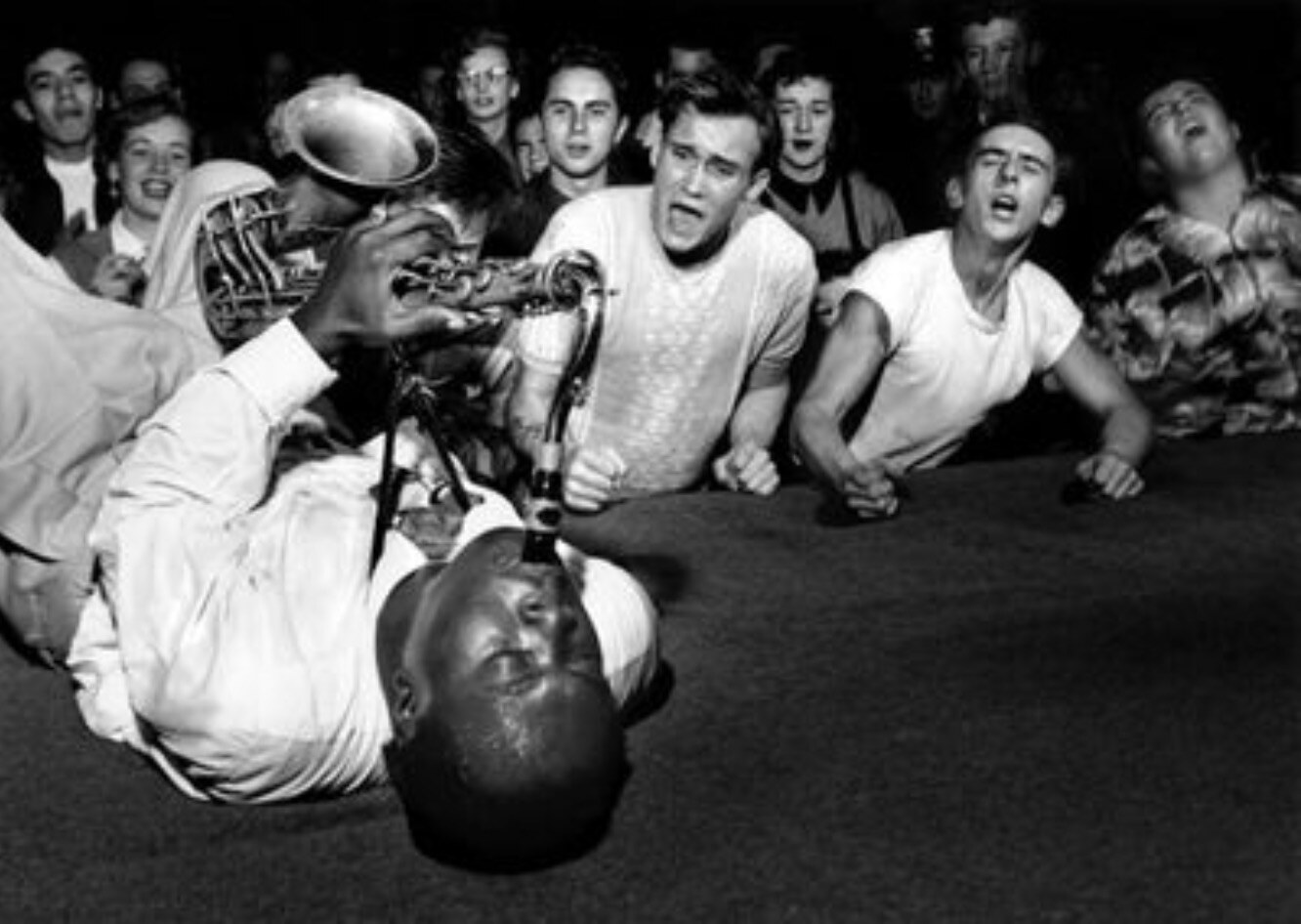

Below is one of my favorite pictures of all time:

The photo, from around 1951, depicts jazz saxophonist Big Jay McNeely in the middle of one of his legendary “honking” stage shows. McNeely’s music is outrageously energetic and fun (see his song “Nervous Man Nervous” or his album Honkin’ and Jivin’ at the Palomino for examples). This is a depiction of a moment of pure human joy, of jazz in ecstasy as McNeely lies on the stage wailing. It would have been incredible to be there at the second this photo was taken.

And yet: a snapshot is a fragment of the whole, and while I love the way this photo shows the communion of musician and audience, it does not escape my attention that the audience is mostly white. McNeely would almost certainly have been returning to a segregated hotel after the concert (yes, even outside the South), and I am not oblivious to the way that the Black-white wealth gap meant that Black musicians depended financially on the patronage of white audiences. The men in the front row may have visited McNeely’s concerts, but they probably went home to all-white neighborhoods and would send their children to all-white schools.

The coexistence of extreme pleasure and extreme pain is a strange thing. The way to deal with the contradiction is not to simply blot out the darkness, but neither is it to get sucked into the black hole, and be paralyzed. The illusions must be shattered, but understanding that there is quiet misery concealed beneath smiling faces does not mean accepting misery as inevitable. It means living authentically, dealing with what your country is doing and what people are really like, and acknowledging the darkness so we can end it.