Raúl Carrillo on MMT’s Connection to Student Debt

Millions of Americans urgently need student debt relief. Modern monetary theory might offer a solution.

Student debt is a huge burden for millions of Americans—around 14 percent of adults are saddled with student loans, with an average balance of over $37,000. A number of solutions have been suggested, from Democratic senator Chuck Schumer’s semi-decent proposal to eliminate $50,000 of each borrower’s debt to President Joe Biden’s pathetic offer to knock $10,000 off that total.

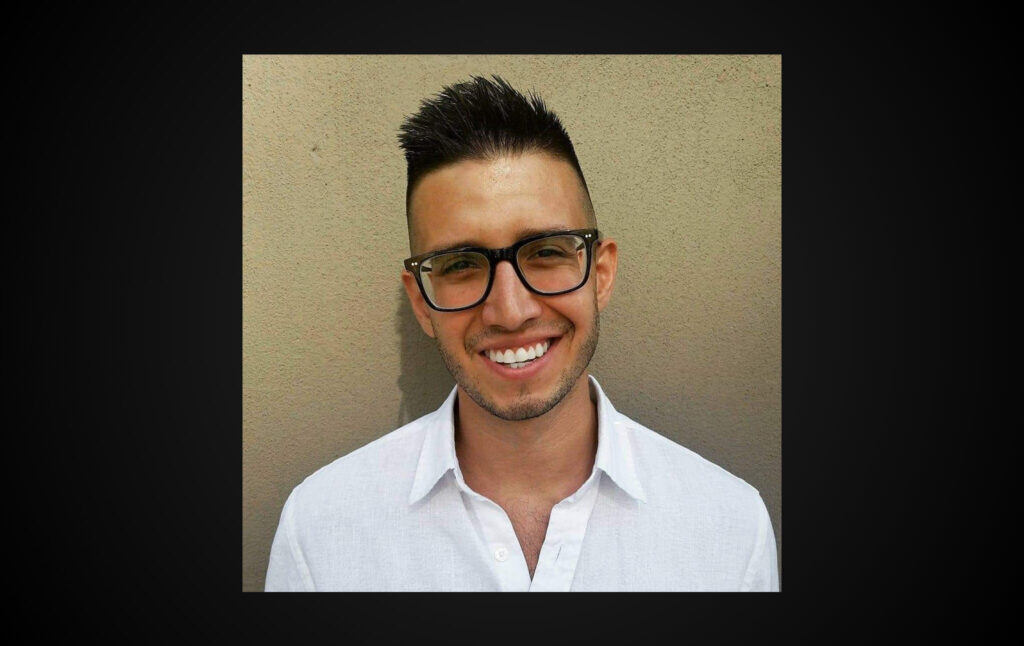

However, might there be a better answer to this rapidly worsening problem? According to Raúl Carrillo, modern monetary theory (MMT) fits the bill. He was gracious enough to join Current Affairs finance editor Sparky Abraham to explain how. Their expansive, surprisingly playful interview on the Current Affairs podcast was never released due to audio quality issues, but now you can take profit of their ideas in written form.

The following transcript of their conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Sparky Abraham

Hello and welcome, Current Affairs Bird Feed, to another super-special extra secret bonus episode of the Current Affairs podcast. This is something of a crossover with the “Is MMT Real?” series, but instead of doing our three main “is MMT real?” questions, we’re going to focus on one issue in particular: student debt. I’m here today with Raúl Carillo. Hey, Raúl, good morning.

Raúl Carillo

Good morning, Sparky. Pleasure to be with the Current Affairs team as always.

SA

Nice to see you again, it’s been a while. Raúl, you now are the Director of Public Money Action and you’re also an associate research scholar at Yale Law School. Before our conversation I didn’t know much about Public Money Action. What is that?

RC

That’s fair. It’s a relatively new enterprise. The MMT community has now expanded and deepened far enough that we need a sort of constant presence on the hill and around legislation and regulation. So we recently incorporated a new 501(c)(4) called Public Money Action which will conduct different activities from those conducted by the Modern Money Network and other organs within the ecosystem.

Thus far we’ve worked on three bills with the Squad. The first is the ABC Act, which provides immediate and constant relief to U.S. households in a private fashion during the pandemic depression. We’ve also worked on the Public Banking Act, which helps incubate state and local banks to accomplish a variety of democratic functions. And then most recently this past Friday Representative Tlaib introduced the STABLE Act, which attempts to bring some stable coin issuance in the crypto space—so an additional currency space, within the ambits of safe and sound banking regulation.

SA

Okay, so you’re a lobbyist. Are you a lobbyist?

RC

[Laughs] That’s a lobbyist laugh, right? I just laugh, I don’t say anything else.

SA

Yeah, exactly, that’s right. That’s actually very cool. Pete and I touched on this a little bit in our MMT series but, you know, the right for a long time has had these specific advocacy structures focused around particular economic theories, for lack of a better characterization. And it seems like it’s been something that’s been mostly missing on the left, so it seems like an interesting strategy that you guys are taking that maybe is underplayed at this point.

RC

Yeah, I mean, I don’t think we’re under any illusion that the balance of power skews left where now it’s very important to shift the Overton window to sort of stake out different places and terrain, and I think to try to gin up energy around some things that actually do have a chance of really passing and making a good effect here. For instance, that last piece of legislation has some bipartisan attraction because people don’t want, like, Facebook to be a private money system, etc.

SA

Mm-hmm, mm-hmm. They don’t?

RC

But yeah, I think in general, “lobbying power” is sort of lacking on the left, and now that we have representatives with roses next to their name on the hill, that apparatus needs to exist.

SA

Yes, look, I didn’t mean to, like, malign you or something as a lobbyist. I actually do a fair bit of lobbying for my day job and I think that it’s an under-recognized aspect of all this work. I think that people who do a lot of local advocacy from a more left perspective recognize the value in it a lot more clearly, right?

RC

Yeah.

SA

You’ve got to be in the room. Like, you’ve got to be in the room all the time. The banks are always there.

Well, I didn’t actually ask you here to talk about Public Money Action, though I’m glad we did, or lobbying. What I really wanted to talk to you about might be sort of a personal saga for me. I’ve written a few articles about student debt for Current Affairs. Student debt cancellation is back in the discourse, although as of this recording it kind of peaked maybe a week or two ago. It’s kind of died down a little bit again now.

But my journey in writing and thinking about student debt started from a place where I was accepting a lot of premises about what exactly it means for the government to give out loans, collect loan payments, how to talk about what it would cost for the government to do X, Y, and Z, what the tradeoffs are. To be frank, I think that in writing about student debt cancellation, I was operating from a premise of believing that if you cancel student debt, you’re going to cost the government money that it can’t put elsewhere. And so a few of my earlier arguments about student debt were basically arguing along the lines of: “That’s okay and it’s worth it.”

But as I have listened and read—and primarily, listened to and read work that you’ve done about Modern Monetary Theory—I think that my conception of what it means for the government to spend money and collect money has evolved and changed. I would probably characterize that stuff differently if I could go back and redo it. And now that the discourse is back, I see these same points being made.

I don’t think that I’m at a point now where I’m comfortable and confident enough in what might be a more accurate way of portraying these things that I could explain it myself, but I was hoping that you could come through and help me out. Since this isn’t necessarily just an MMT series podcast episode, maybe you could just start with a broad overview of what exactly Modern Monetary Theory, MMT, is, and then talk a little bit about what you have seen from your perspective about what this way of thinking can bring to the student debt cancellation discourse.

RC

Absolutely. I very much appreciate that introduction, Sparky. I think you framed things really well and to answer your last question first, you know, most people know MMT—Modern Monetary Theory, or Neo-Chartalism as it’s known in academic circles—as a sort of counter-paradigm to the bundle of assumptions that you just laid out.

People, I think, are very familiar with MMTers, specifically Dr. Stephanie Kelton, saying that the United States government does not face a solvency constraint, it faces a price stability constraint. It should be spending money with concern primarily for price stability rather than in broader macroeconomic effects. Rather than merely, you know, money in, money out.

But that is a thesis, right? That flows from a way of looking at things, and fundamentally I would say that Modern Monetary Theory, even though it’s mostly known as a body of macroeconomic thought, is an interdisciplinary project that draws on quite a few strands, including the law, and this is a helpful way for me to approach it as a lawyer. But I think it’s also a helpful entry point for people who think about it just as a participant in the economy—as a student debtor, for instance.

So the way that I approach the core tenets of MMT, is that it’s not, again, about the specific programmatic theses. It’s about recognizing that money is a creature fundamentally of public law and governance. And this is a position that’s shared not just by MMTers but by plenty of legal scholars—for instance, Christine Desan at Harvard Law and a lot of folks who have dug into the imperial way in which monetary systems expand across the globe, whether they’re controlled by governments or corporations or multilateral institutions, etc. But recognizing that money—thus the monetary system, and thus the public finance system—are just as much legal-social-political constructions as markets, is, I think, the big MMT core insight. When you bring that to debates about policy—for instance, the student debt cancellation debate—you zoom out a bit and you look at the system differently.

As a student debtor, I was inclined to believe that I have to cough up so much money for the program to work for all of us student debtors as a whole. And I’m set comparing myself against other debtors, against other constraints and metrics. It’s in a different context, but when we’re talking about the government’s financial approach to something as fundamental to reproducing society as education, we really have to zoom out and think about, again, first premises.

Why is the system set up this way? What sort of relationships attend a system within which the government lends money rather than spends money or even invests money in the U.S. public and in students? There’s a lot tied up from step one, and so going back there I think is first of all critical to the debate, and that’s what MMT helps with.

SA

So let me give you a very crude argument, as I’ve heard it, about student debt cancellation, okay? And maybe you can help me identify all of the ways in which this is wrong. I think if it was just me I could probably identify a few of them, but you might be able to identify a few more.

I think a very crude argument goes something like this: There’s about $1.7 trillion of outstanding student debt. That debt is held, kind of definitionally, by people who have gone to some college (although I’ll note that it also includes a lot of loans to parents too, but definitionally it is related to people who have gone to some college). Some research out there says that the higher debt amounts individually are held by people with relatively higher incomes.

So why on Earth would the government give up $1.7 trillion of revenue in order to help these people? Why wouldn’t the government just use that $1.7 trillion to help people based on their income or based on their wealth or something like that?

RC

Yeah, I hear this question come up quite a bit as well. This is, of course, what happens when we’re taught to think that the government takes in money from us and then it redistributes it and there’s nothing more sophisticated going on. But we’re really talking about what I would argue is the most complex financial entity in human history, the U.S. federal government.

The power is monstrous, and it’s funny to me that people who are willing to make so many American exceptionalist arguments about the general power of the American government feel that it can’t manage to forgive student debt in a way that keeps the system stable when it runs the rest of the entire global economy, right? I’m not trying to lean into its power here or say it’s a good thing necessarily, but it almost beggars belief that the United States—which is engaged in things like swap lines with the major central banks in the middle of the night across the globe in a criss-crossing pattern that determines all of our futures, like whether famines happen in the global south or not—that the United States cannot figure out how to deal with the U.S. Department of Education’s accounting trick here.

Fundamentally MMT says that you have to think of terms in sectoral balances. The government creates money and, from a legal perspective, that is part of what it means to be a government. The government doesn’t have to ask to create property, it doesn’t have to ask to create the contract, it doesn’t ask to create corporations. It just does these things. The formation, the creativity, is a power that is attendant to being a government in the first place. Of course that’s wrapped up with issues of private control, and wrapped up with geopolitical constraints, etc. But fundamentally what we’re talking about is a United States government that sends money on purpose into the economy as a tool that it controls in order to have an economy in the first place.

And the Supreme Court has made it very clear the government can issue as much money as it wants, whether lending or spending. Of course there are economic considerations, but legally there’s nothing questionable here. So the question then becomes: if it’s not going to have shitty macroeconomic effects, why are people paying for higher education in the first place rather than the government simply paying for it?

As your work has shown, this is the approach in many places in the world. This was the approach in New York for a while and California for a little while even though you face different constraints at the state level than at the national level. But in order to attack higher education as a pillar of democracy, what we saw Ronald Reagan do in California, for instance, is start to say that education is a privilege. And this leads to saying that what we need to happen is for the U.S. public to pay the U.S. government for a service it’s providing when it provides education. As if the US didn’t create the public education system. As if it doesn’t play all these money games all the time, right? And the U.S. Department of Education does do some of its own accounting, but that’s within broader Treasury and Federal Reserve accounting.

I think that scholars and activists in this space have been very clear that we want the directionality to change. We believe, as you’ve written, that higher education is something that is just as critical as K-12 education. And this is especially true if we want a racially just society, it’s especially true if we want to start attacking questions of power on gender lines, and not just be concerned with these sort of paper spreadsheet effects of moving numbers one way or another. Who cares if the government is going in the red? If it’s something as critical as this. We don’t ask how much money it costs to do some of the most fundamental things in society, good and bad, right? Like blowing shit up. We don’t audit the Pentagon. We have no idea how much money the government spends defending and massaging and maneuvering the property claims of rich people, and yet when we get to student debt it’s suddenly the only relevant question.

SA

Right, right. What you just said brings up a lot of questions, and I think there are a number of different directions to go. When I was thinking about student debt very early on, one of the crude concepts that came to me was, “Well, this just kind of looks like a tax.” If I have to pay money to the government because I couldn’t afford college, that seems like a tax on people who can’t afford college.

But then I kind of talked myself out of that for a while. I started thinking, “Well, maybe this is a little bit different, maybe it’s not quite a tax, maybe it’s something else.” And now I feel like I’m coming full circle, and coming back to seeing student debt payments as more similar to taxes. You can tell me if this is a totally wrong understanding of MMT, but I think one of the bigger picture points that I’ve taken away from it is basically that you can zoom way out. And when you zoom way out, one heuristic for thinking about government collection of money and spending of money is something like: whenever the government collects money it’s basically equivalent to destroying it, and whenever the government spends money it’s basically equivalent to creating it.

So the question is just whose money are we going to destroy, and whose money are we going to create in order to maintain whatever balance we’re trying to maintain.

If what we’re trying to accomplish is broad societal goals, why would we choose the group of people who wanted a higher education and couldn’t pay for it at the time to burden with whatever accounting we need to do to accomplish those goals? I wonder what you think about that.

RC

So I fundamentally agree with you, Sparky, that framing things in terms of taxes and repaying the government is helpful, even if there’s a lot of nuance to be discussed there. People understand taxes, right? People seem to be pretty clear about when the government is taking money from them on their paycheck. Because that’s the media narrative. And white middle class folks, for the most part, are inclined to think of payroll taxes and income taxes as taxes— but not student loan interest, not fines and fees for things like driving while Black, not having your car impounded. Not all the bullshit that piles up on top of child protective services and just all kinds of nickel and diming that happens for poor and working people.

I think conceiving of student loan interest and student loan payments in general as a tax is actually quite helpful. Because the student loan system is saying, “You go about your business and then you owe us this money,” as if it’s something you should feel obligated to the federal government for. But this seems like a good moment to pause and think about the purpose of this system and the purpose of taxation. Do we normally use taxes to get people’s buy-in to a system, to put them on the hook financially even if it disempowers them?

The funny thing is that a lot of economists will tell you that a key purpose of taxation is to discourage the activity that’s being undertaken. So what the federal government is essentially saying is, “We’re going to establish higher education, mostly at the state level, where they’re not able to fund it appropriately, then our answer is going to be that you have to go in debt to pay for your education,” and only certain people are going to be able to do this and certain people are going to take on more burdens doing this.

And the government demands revenue while at the same time fundamentally disincentivizing people from getting higher education. That combines with the failure to regulate well and over time people, I think, are starting to say, “What the fuck is even the point of this?”

SA

And you see this explicitly in some of the takes, right? Particularly the conservative takes. They’ll be like, “Well, if you didn’t want to be in debt you shouldn’t have gone to college.”

RC

Right.

SA

Or and you start to see the stuff where it’s like, “Well, you know, college isn’t for everyone.” And yeah, of course that’s the direction that you end up going when you have this system. One of my main points is if you think that these are bad takes you should be against college financing, period.

RC

Maybe even K-12 financing.

SA

Well, absolutely K through—everything. This is a whole other point, right? I feel like it’s almost a dangerous point to make because there are people who would feel this, but I have yet to hear a good argument from folks who think that financing from college is good, or at least okay, as to why financing for high school wouldn’t be good or okay.

RC

Yeah, I’d love to hear [neoliberal economist] Jason Furman on this point.

SA

Actually, maybe we should try to get him.

RC

Go on Current Affairs, Jason.

SA

Yeah, exactly. I’m really glad that you described all of these other payments to the government that people don’t think of as taxes. You also said something in there which is that it’s about what people feel obligated to do—which I think you can kind of import to these other things, too, right?

There’s a very different moral dimension between, say, how people feel about income tax versus how they feel about student debt versus how they feel about court fines and fees. I think when you talk to a lot of people, there’s some notion that taxes are deeply social. Like if they’re kind of on the more “progressive” side it might sound like, “This is an overall civil social project and so we want to contribute to the taxes to make it work.” And if they’re on the conservative side then it’s more, “This is something the government’s forcing me to do at gunpoint, to contribute to these taxes.” But it’s not about me. In neither case is it about me, the taxpayer.

But when you talk about student debt, when you talk about child support, when you talk about court fines and fees, there it is a personal, moral obligation that I think people identify. They say, “You agreed to this,” or, “You did something that resulted in this.” It becomes about the person who is obligated in a moral sense, both internally and from other people’s points of view. To me that just seems like an unhelpful way to think about what exactly we’re trying to accomplish with these systems.

Doing that is muddying our goals. If we’re trying to encourage people to go to college, it’s just not that helpful to say, “Well, yes, sure, maybe taxes disincentivize education, or maybe the student loan system disincentivizes education or yes, okay, we can concede some of these points, but people agreed to it and therefore there’s a moral obligation.” What is that obligation achieving?

This also relates to something that you wrote about in your MMT piece for Current Affairs, which is this idea of the upstanding taxpayer. The idea that if you pay your taxes, you are a socially responsible person, and how that filters down to then cut people out of the kind of social and civic society by morphing into, “If you don’t pay taxes—and a large portion of the United States is essentially too poor to pay taxes—then you get relegated to a lesser status.”

This is an impossibly big question, but what’s the right way to think about how morality and desert should fit into our ideas of who should pay what when it comes to paying into the government, letting the government destroy your money as opposed to somebody else’s?

RC

Yeah, the big question, right? I’ll do my best here. Fundamentally I think it’s helpful to just name that a lot of wonks in the space have no idea who student debtors are, and this goes to the point about, you know, who do we imagine is an upstanding taxpayer? Who do we imagine is an upstanding student debtor?

I remember the first time that I read about student debt while I was a law student. Kevin Williamson at the National Review wrote that we were trying to subsidize, I believe the quote was, underwater basket weaving for moonshine at, like, Smith or something like that.

SA

Oh, they love underwater basket weaving. Jesus Christ.

RC

Right.

SA

That never goes away.

RC

Right, right. It was just immediate misogyny and it was awful. But I think that’s a core issue. Most people do not realize that most folks working minimum wage jobs have some kind of post-secondary education,

SA

Yes.

RC

Most people do not realize that folks who are exploited and oppressed for a variety of reasons find themselves facing a fundamentally shitty choice between a shitty job and shitty student loans. So if you want to talk about meritocracy, you need to talk about labor and household debt and everything in a broader frame. I get that people jump to individual morality immediately and with debt how could you not?

That’s how capitalism operates, and I think it’s very important to consider how we relate to each other within it. I have to consider where I am. I have law school debt that is a number figure that is certainly, like, qualitatively higher than a lot of people who have debt that is a lower number figure, but their lower numbers are often more difficult to deal with, right?

That’s all extremely important and has to be prominent. That being said, we are already losing the game when we are trapped here looking at each other saying, “How much do we pay?” Because what happens to this money when it’s paid back?

SA

What does happen to it, Raúl? What happens to it?

RC

Well, it’s on the Department of Education’s balance sheet as, like, black ink, which is great.

SA

Okay.

RC

Now the Department of Education, of course, if you take a consolidated balance sheet perspective, is not losing any money. And for many years, in fact, [law professor] Frank Pasquale and a lot of other people wrote about how, for instance, income-based repayment [IBR] was creating a financial return.

So one of the student loan perennial claims is returning money to the government is important, but to what end? The government gains no power to better distribute jack shit because of your and my student loan payments. And let’s also not pretend that the numbers are real. There’s no reason the total value of student loans on the Department of Ed’s books is relevant.

SA

Right.

RC

Like, that $1.7 trillion figure is not what’s going to be paid. It’s going to be filtered through IBR and these other programs, it’s going to be subject to broader macroeconomic conditions, it’s no more relevant than the capitalized value of future tax revenues for the entire government.

We fundamentally do not know what that number is, and as [economist] Jamie Galbraith has said, the entire federal budgeting process creates an illusion of control when we freeze all the important variables. Like, what’s going to happen with people’s incomes across the stretch of the pandemic? That number is nonsense. So I think that folks like Jason Furman, a lot of the other centrists, are making sort of silly numbers as to how much money is going to be accrued by the government, how much money is going to be lost, what the multiplier effect is, etc.

But fundamentally it does not matter.

SA

Doesn’t matter.

RC

It doesn’t matter. It matters in the sense that it reflects, as we’ve been discussing, a certain set of moral and social obligations in the way that we’ve chosen to run this system. But it doesn’t make it systemically more difficult for the Department of Education to provide, or for Congress to provide free higher education, for instance. This is either debt that people have or it’s a ridiculously manipulated asset on the federal government balance sheet.

SA

Right, and just to make the point more clear, in some sense before it gets to the Department of Education… this money has to pass through student loan servicers, each of whom gets a cut. These are federal contractors whose sole purpose is to collect the money and then pass it to the government.

They get paid quite a lot of money in order to do that, just a super unnecessary role, and in the meantime they lie to people in order to make more money for themselves. The government even has ongoing contracts with companies that it is simultaneously suing for lying to people under those contracts.

RC

Absolutely. And I’d be happy to just pause for a moment and talk about the private actors in this space, because they’re the ones really pushing a lot of these narratives. I mean, I know a lot of folks who I agree with about a great deal who still think that we should just cancel low balances for racial justice reasons. And I can have constructive arguments, or conversations, I should say, with those folks.

But when that comes out of the mouths of Navient, or fucking SoFi, you really need to question what you’re saying. Whose interests are you arguing for?

SA

Yeah. So you know a lot about this. I actually want to get into this for a second. Let’s talk about all of the different industries and industry actors that are putting forward arguments, because a lot of people miss how these arguments are in those companies’ financial best interests. So from my perspective the most obvious ones are the companies that service federal student loans.

This is Navient, Great Lakes, FedLoans and Nelnet, I think, are all still servicing federal direct student loans. They all get paid by the Department of Education to collect student loan payments, and so if student debt gets cancelled they will each lose their contracts, which I think are generally in the sort of hundred million dollar a year range, if I remember correctly. They might have changed, I think they’ve gone up and down, but that’s kind of the order of magnitude that they’re on. Does that sound right to you?

RC

That sounds about right, yeah, and the servicers is definitely where I’d go first.

SA

Right. This is the most obvious, most direct financial benefit, and these companies are out there making the arguments, funding the symposia, funding the think tanks, lobbying the legislators. I remember I went to a kind of panel discussion, I think it was in the Brookings Institution where every panel had either one or two people from a student loan servicing company or from the student loan servicing trade group. They had some good people too, including legal aid attorneys who help people with their student loans, but they had industry on every panel! And no one ever addressed the fact that these companies are arguing in their financial interests. It all gets this “we’re just a bunch of wonky experts doing policy” gloss.

So that’s the student loan servicers, and they’re one of the more egregious examples just because we know from, for example, the CFPB’s lawsuit against Navient, just how awful they are. One of the aspects of the CFPB’s lawsuit is that there are programs for people who can’t afford their loan payments to get into income-based repayment. And whatever you think about IBR structurally, it is extremely helpful on an individual basis. When I was working at legal aid on a fellowship I absolutely could not have afforded my student loan payments and I was on income-based repayment. I think my required payment as a result of that was like $35 or something per month whereas it would have been around $1200 a month on a normal payment plan.

Anyway, these programs exist, the servicers are supposed to put people in them when they can’t afford their payments. Yet one of the things that the CFPB alleges Navient was doing, that I think there’s good evidence for, is if you called Navient and you said, “I can’t afford my payment,” they would not put you on income-based repayment. they would put you on deferral or forbearance, which means that you’re not required to pay anything for a few months but interest keeps accruing during that time.

Those months do not count toward any forgiveness program like IBR would, it does not help your credit in the same way, and you end up owing more money. But getting people into IBR takes more time for Navient to do, so it would push people into forbearance instead to save itself money at the students’ expense.

RC

Yup. Sounds like a pretty clear Dodd-Frank unfairness violation to me, but what do I know?

SA

You would think, yeah, you would think—yet here we are many years into the lawsuit and the federal government’s still contracting with Navient.

But help me understand some of the more obscure players. Because in addition to the companies that straightforwardly service the federal debt, who would obviously lose out if the debt was cancelled, we’ve got companies like SoFi. What does SoFi do?

RC

So, Social Finance is a—they’ll still call themselves a startup—but I think they’ve been around nearly a decade now.

SA

Startup just means nothing. Is Uber a startup? I don’t know.

RC

Yeah, it means “we had a post-2003 idea.” Anyway, Social Finance is a company that came out of Silicon Valley nearly a decade ago now that called itself the Uber of student loans. The idea is to give a kinder student loan refinance. They went after high-earning, not-rich-yet borrowers—they targeted law students, medical students, professional students at specific campuses to eat up the juiciest tranches of debt and to refinance people and create more asset-backed securities.

This has been going on for a long time. We neoliberalized higher education like the end of the ’60s, ’70s with the student debt system as an alternative to just providing money for education. By the ’90s Sallie Mae was bundling and selling debt on the secondary market. [Think mortgage-backed securities but with student loans instead of mortgages.]

This moved the loans off their books, so they could continue to issue more loans, and the risk moved onto the books of private players, before 2006 at least, who now get a say over how the student financing system works. These are called student loan asset-backed securities.

SA

SLABS.

RC

SLABS. Which is, it says it all, right? But we are really being sort of bet on in the same way that mortgages were in the run-up to the great financial crisis. There are some key differences, mostly that the public/private student lending program, at least key aspects of it, were shut down by Obama in the middle of his administration. That being said, the private loan space still runs on securitization.

And especially scary are these companies like SoFi, which started by finding the high income not-rich-yet student borrowers, but are now using data mining and collection and algorithms to just find all kinds of debt all over the place and package that and sell it. So Silicon Valley is starting to get involved in the student loan system.

Perhaps their approach to it is best encapsulated by a Super Bowl commercial, and I don’t know if you remember this from a few years back. SoFi had a commercial where they followed various yuppies around what I assumed was a Manhattan street and they said, like, “Kevin is great. Lourdes, is she great? I don’t know. Kyle is great, look at Kyle.” And we follow him around and, like, “He’s got a SoFi loan. Like, Agnes, I don’t know,” and it’s this sort of ridiculous commercial that’s literally saying, like, “Give us your data, and we’ll tell you if you’re great or not. And if you will be a better indentured servant to the federal government than other people.” That’s a line that I see on the increase.

SA

Yeah, yeah. That’s totally what they’re going for. I don’t think we really need to get into the fact that SoFi is also wracked by sex scandals and stuff.

This isn’t really what I had planned for us to talk about, but I’m glad we are. You can tell the story of student debt financing and I think there’s a piece that a lot of people miss. It starts with the Higher Education Act in 1965, and it’s kind of this gradual process of student financing growing and growing and growing. But as you said, up until the Obama administration, and especially through the ’90s, most if not all of it was privately financed, federally guaranteed.

That was the structure. The federal government says “Okay, banks, if you want to go out and lend to people who want to go to college we will guarantee those loans.”

RC

How could this go poorly?

SA

Right, right, exactly. So Sallie Mae in the ’90s is a private lender out there making private loans that are guaranteed by the federal government, and it begins packaging those loans and selling them as securities at the same time that this is really coming into prominence for mortgages and other assets, anything with an income stream. If people are required to make payments on something then you can make it into a security and sell that income stream to other people.

RC

‘Merica, baby.

SA

Exactly. Greatest country on Earth. And then—I don’t think that it all happened under Obama—but there’s a process of moving away from private loans and toward federal direct loans. I don’t know offhand exactly how that happened, but increasingly you get the government lending to people directly rather than providing a guarantee for private banks to lend to people. And this culminates when Obama ended what was left of the private guarantee program, meaning that all new federally-related student loans now are federal direct student loans: loans directly from the federal government.

What happened to the private industry? You can’t securitize and sell federal loans because you don’t own them, the federal government owns them. So the industry needs a new way to get back into this space. The way that they do it, at least that SoFi does it, is they say, “People are paying relatively high interest on their federal loans.” I mean, for my law school loans, a lot of them I’m paying 7.65 percent, right? So SoFi says, “We can pick and choose the people who we think are going to pay back and offer them a lower interest rate.”

As you explained, they went first to the super prestigious schools and now they’re kind of relying on some algorithms to determine who’s going to be the ones to pay back their loans. But if SoFi can get people to agree to their lower interest rate, then they own the loans, and they can securitize them and sell them to Wall Street. So their pitch to debtors, to me, often, that I get in the mail, is, “You could save a bunch of money if you let us take over your debt, because we’ll charge you less interest than the federal government is charging,” That’s true, and there probably are people who have saved money doing this.

RC

Without a doubt.

SA

Yeah, but the other thing that happens is that you are changing the character of this debt relationship. Because if you refinance with SoFi, you are no longer obligated to the federal government. Now you have a new loan and you owe it to SoFi. I think that’s an importantly different relationship in terms of what is happening, what your student loans are. If they’re still similar to a tax, they are a tax that has been paid in a large chunk at one point in time rather than stretched out over a long period of time, right?

RC

Yes, and I think from a critical legal perspective or a legal realist perspective we would say this would amount to the government creating taxes for SoFi.

SA

Creating taxes for SoFi! Exactly!

RC

Which begets the question of, like, why are we doing this? But SoFi is popular because it’s marketed precisely at this attitude that we’ve been discussing—that you can be an honorable debtor, or one of the best debtors, right?

SA

You could be good.

RC

Right, and this is bullshit. Like, as David Graeber, rest in peace, said, like, “All honor is the extraction of surplus dignity.” And what we’re talking about here is a system whereby people have to pay the government to learn or to get a job. I’m extremely sympathetic to the argument that a lot of college or post-secondary education is not particularly helpful to people, and obviously, we know that from experience in the for-profit college space. But in general, people are trying to develop some level of stability, which is especially important for households that would have been considered to be property and people who’ve been oppressed and exploited through the very higher education system.

It still is the case today that, as soon as you step back on these basic questions, the financing system ceases to make sense unless you take into account the ideological reasons. Specifically, the fact that Reagan was saying, “You’re not going to use tax dollars to study Black Pantherism and be gay at U.C. Berkeley. And you’re not going to protest and do your commie pinko shit on the taxpayer dime.”

So that’s actually a big genesis of this entire nonsense system at the federal level, which is already on top of the deeply unjust K-12 funding system. We are so down and deep into framing that we’re looking at each other like crabs in a bucket, and I think MMT and this broader discussion that we’re having about legal design helps to reframe that.

SA

Yes. This is an important point, too, because some of the time you still get these Kevin Williamson-style underwater basket weaving bullshit framing an argument about the liberal commie college professors and whatever else, and I think that a lot of people want to handwave that away and say, “Well, you know, this is just culture bullshit that the conservatives are on, that’s not really the material stuff, we want to talk about the material stuff.”

But actually this is the link, right? The arguments about how to finance higher education rest on moral premises, but those arguments’ purpose is then to allow private companies to collect tax, from a specifically vulnerable set of people.

RC

And yet they will find common cause with means-tested racial justice arguments that come from the center of the Democratic Party,

SA

Yes. Something else that you brought it up a couple times, but I just want to note this point: you’ve mentioned for-profit colleges, you’ve mentioned how the burdens fall harder on nonwhite students in a lot of different ways.

I think that I came to this point through Marshall Steinbaum, though I’m sure other people have written about it. There is an employment discrimination-driven dynamic where people who cannot get ahead in their workplaces or cannot get into workplaces for reasons that aren’t actually related to education, feeling like they need to go out and get degrees in order to succeed at work. This then drives a lot of the student debt, and explicitly informs the marketing that the most predatory colleges do. I always think back to Heald College in the Bay Area, whose slogan was “Get in, get out, get ahead.”

RC

That’s an excellent example.

SA

I think we’ve wound our way to a somewhat different point, but I’m glad that we’ve gotten there. To go back to the broader MMT point, is there anything else that we need to think about or keep in mind? If you were to do a short explanation for someone who maybe isn’t an economist, isn’t involved in the online discourse, is a nice liberal Democrat with decent values who worries about government spending, how would you make the MMT-informed case for debt cancellation?

RC

Excellent question. It’s different strokes for different folks and depends so much on where people are. If I’m talking to a Democrat, I’m going to talk about Ronald Reagan before I mention MMT. And we first have to talk about what function higher education should serve. Fundamentally I think the key is getting people to understand that we’re not talking about flipping a switch, but integrating our thinking about money with our morality and our theory of power.

The conversations about morality can be informed by the question of what do we really want? That’s not just financial. The arguments that emanate from the center of the Democratic Party are very much paper stuff.

SA

Right.

RC

So maybe when you’re talking to the average Democrat, it’s, “OK, so there are paper effects, like who literally has more or less, i.e., nominal debts and assets on the balance sheet. Then there’s what cancellation might do to the structure of the whole endeavor. What it actually means to change spending and saving conditions for someone in a context like the pandemic. At the end we need to keep our mind on the real impact as opposed to just the spreadsheet impact of any proposal.

You can be a really smart person on the center left and say, “Look, if I only eliminate lower balances, that makes the gap between Black and white student debtors smaller.” Well, that might be true on some metrics, but that’s also an extremely narrow question that divorces the broader financial situation and social situation that people find themselves in.

SA

Right.

RC

[Sociologist] Tressie McMillan Cottom makes the excellent point that people are just going to take whatever shitty student financing deal they can get as long as they don’t have a job guaranteed. Or as long as there is not any modicum of a possibility for stable employment without it. Some people do manage to improve their station through education, and these options should be more plentiful, but we have fundamentally created a set of shitty individual options because we’re stuck in this discourse that fucking Ronald Reagan created for us.

SA

Absolutely. I know firsthand from my own journey on this stuff that there is no switch you can flip. You need to have constant repeated conversations, contextualizing, backing out, looking broader, which is why I really appreciate your work and your willingness to come back and talk about this stuff over and over again. On one of my older student debt pieces you were someone who came on Twitter and gently nudged me in the right direction. We have to keep having this dialogue and this conversation and keep making these points, because as with anything you can’t just change someone’s mind in an instant.

RC

Your work has been just as informative to this space for me as I hope mine has been for you. There’s a lot of people just doing excellent, excellent stuff out there. Danielle Douglas-Gabriel does some great coverage at the Post.

Just because I haven’t mentioned it yet, I would say that people should definitely check out Luke Herrine’s work on student debt cancellation which informs Senator Warren’s proposal. Luke’s article is in the Buffalo Law Review, called “The Law and Political Economy of Student Debt Jubilee.” His point is that the education secretary can exercise something tantamount to prosecutorial discretion to just get rid of all federal student debt. So mechanically there’s an easy way to do full cancellation.

The question then becomes, “Do you value the same sort of vision for society that you and I are discussing?”

SA

Yeah, and a huge credit to Luke in that article. I think that article really blew everything open. I am constantly impressed by the extent to which Luke Herrine has managed to shift this whole conversation in a really positive direction.

Okay. Well, thanks so much, Raúl, this has been really great. Is there anything else that you want to plug for yourself, not just in terms of this topic? Where can people find you?

RC

Sure, people can go to the Law and Political Economy Project website. I’m not here as representative of that project, but that’s where to reach me in an official capacity. Otherwise, you know, I’m around.

As a final note I’d say to everyone, myself included: keep following the activists, keep following the Debt Collective, keep following all the folks who have a very, very real interest in this and provide a different perspective from this spreadsheet-focused idea that emanates from the core of the Democratic Party.

SA

Great. All right, this has been Current Affairs, thank you. See you all later.