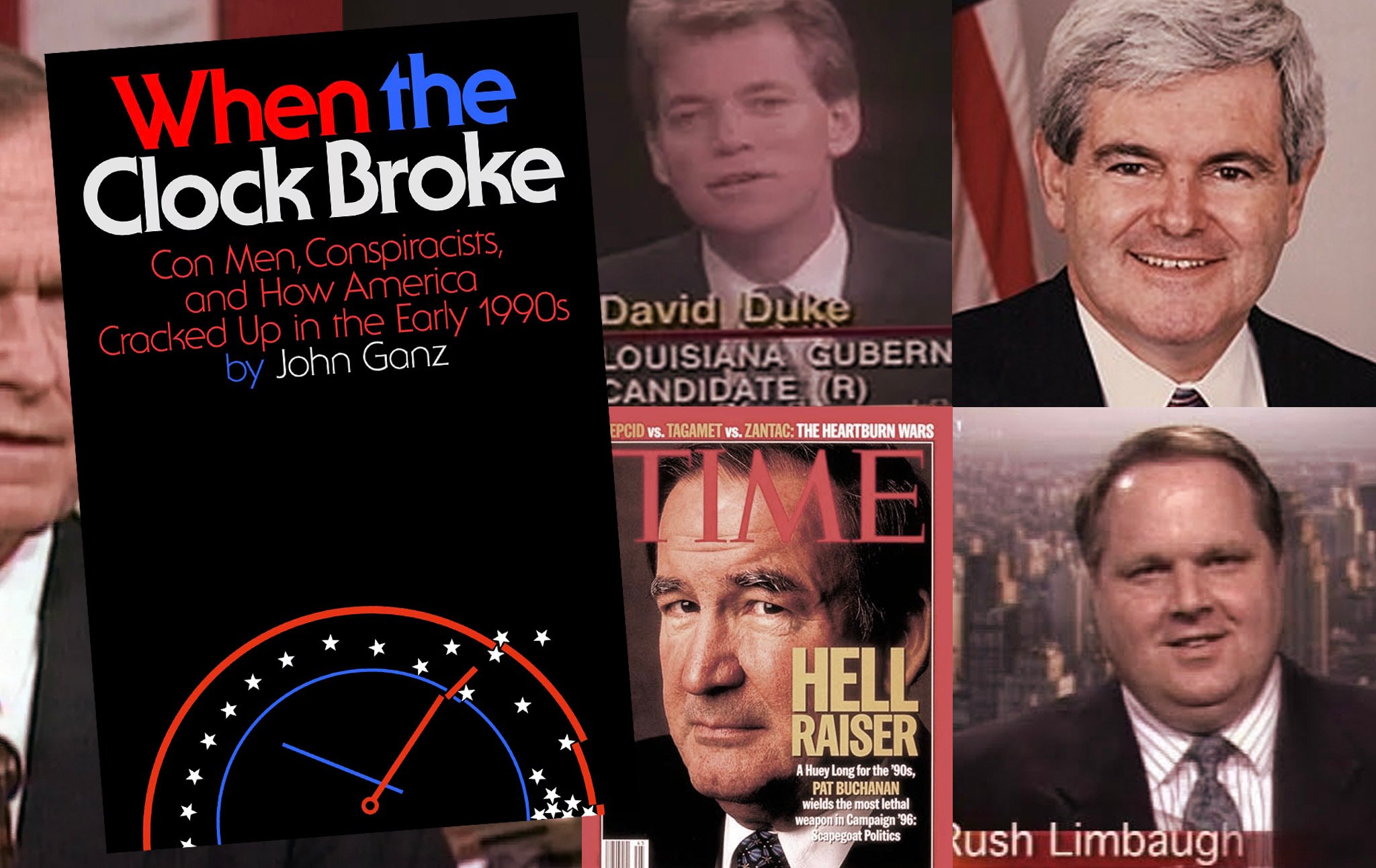

John Ganz, author of "When the Clock Broke," argues that '90s right-wingers like David Duke and Pat Buchanan forged the template for Trumpism.

Ganz

Yes, absolutely. I have to say, a part of that was a conscious, almost aesthetic decision, because I didn't want to beat the reader over the head with it. But when I wrote this book—I really got going on this book in early 2021, so Trump's political future wasn't assured yet. So I knew that this stuff was going to be important. And it was definitely about the origins of Trump, but I didn't know exactly how important Trump was going to be. The other thing that I think is really important to realize is a lot of times we think of Trump as a sui generis figure and being a real original. But then you realize, well, he was kind of soaking up a lot of these different things.

There was a great recording—I keep on finding things from the period that would have been so perfect for the end of the book. Trump's on Larry King, and he had just seen Pat Buchanan, David Duke, and their asking his opinion on things, and he said, Well, I think they're going to be very successful, because there's a lot of anger out there in the country, and they're channeling it. He puts it in his own specific way.

In a certain way, I've advanced this idea in my newsletter a few times, Trump is very stuck in this era. His fixation on tariffs and immigration, particularly tariffs, is something that was big in the minds of people like Perot and Buchanan, because this was an era where the United States felt like it was being overshadowed by the export-led economies of Japan and West Germany, or then just unified Germany, and South Korea. So the idea that the United States really had to protect industry was a huge thing that was present at this time, and many politicians talked about. Then that kind of doesn't happen, partially because the neoliberal side of the Clinton administration wins out in the policy debate, and partly because the Japan bubble bursts and the trade threat seems lesser, and the idea of a kind of guided or managed economy looks less attractive. Everyone says, Oh, well, Japan tried that, and look at them now.

So there are all these weird little moments of historical contingency too. But with Trump, you have to have a little bit of a time machine to understand what he's talking about. Also, when he talks about disorder in cities—the crime rate in the era of the book I'm talking about is really extraordinary; in the early 1990s, for a couple of years, there were around 2,000 murders in New York. That is really significantly more than what we're seeing now. Even the fixation on public disorder. This idea of troops in the cities? Well, during the LA riots, the Insurrection Act was actually invoked, and there were Marines on the streets of Los Angeles. Now, it was a true instance of public disorder. One could argue whether it was justified or not or needed. They arrived too late, really, to do much of anything except pose for the cameras. Buchanan went out and posed with them, and then his famous cultural war speech at the Republican National Convention uses imagery of true American troops on the streets of American cities "taking back the country." And these imaginary themes, these fantasies, just really animate both Trump and his whole America Firster MAGA movement.

Robinson

If Trump is a kind of anachronism in that way—a creature who belongs in the 1980s and 1990s, who is an amalgam of David Duke, Pat Buchanan, and Ross Perot—that raises the logical follow-up to what you've just said: why has he been so successful in the 2020s?

Ganz

Yes, I think that's an interesting question. I think a lot of other people are also stuck in that era. But I think a lot of the issues that he speaks to actually accelerated and got more severe. The kind of deindustrialization of the United States, which had begun in real earnest in the era of my book—it's going on, and it's severe, but it really takes off in the 2000s. Then you have the financial crisis at the end of that decade. And so you have a real change in the material basis of the lives of middle-class Americans and a real decline. You have an economy that has wage stagnation. We have a lot of cheap goods coming in, but not a lot of job security like we had in the middle of the 20th century.

So a lot of the same processes just become more severe. And there were a lot of racial anxieties, to put it mildly; those increased. And the 1980s were also a decade that saw, for the 20th century, a high amount of immigration. Since the early part of the century, it was the decade that saw the most immigration. And Reagan, in his rhetoric and behavior, was pretty welcoming. He was not an immigration hawk. He passed an amnesty, which really upset people on his right. And his final speech, the city on the hill speech, is about America as welcoming, as a beacon to the rest of the world. But the demographic changes in the country and their perceived economic effects were really a preoccupation for Reagan's right, and Reagan's right tries to assert itself after he leaves the scene because they viewed H.W. Bush as this kind of establishmentarian country club Republican liberal, almost, which, of course, is not really true. He was quite conservative, but that was their perception of him. And then you have the establishment of the Republican Party, and this is also key. The establishment of the Republican Party kind of vanquishes the forces that I outlined in this book. But by the time 2016 rolls around, the establishment Republican Party has really discredited itself with the war in Iraq and with the financial crisis. So Trump has easy pickings. He has a very disorganized and really hollowed-out GOP to fight against.

Robinson

And the Duke campaign is one example of a sort of case study on a local level of what it would look like if the establishment Republican Party was unable to keep the Nazis out anymore.

Ganz

Yes, exactly.

Robinson

You kind of shy away—and I take it it's deliberate, because you indicate in the afterword that it's deliberate—from doing causal analysis or trying to tell a big story about the historical forces at work underlying it. You stick to the stories and present this kind of kaleidoscopic picture of America during this time, from the LA riots to these sorts of white nationalists, and let the reader draw their own conclusions. And so we get this kind of picture, and we feel the ingredients of the present coming together steadily. You see a part of it here, a part of it here, and a part of it here, and you go, Oh, I see it. But do you have a kind of theory of history here in which this period relates to our present?

Ganz

Yes, for sure. So if you read the introduction, you notice that I really begin with the crisis in the U.S. economy. I talk about how the structure of unemployment and wealth in the country changed under Reagan, and I think that was really decisive. And then the next thing, in the introduction, I also talk about Antonio Gramsci and his idea of organic crisis, or crisis of hegemony, and that's when the political leadership is no longer able to lead and its story about the national direction is no longer taken seriously.

It's not exactly class struggle. It's a struggle between the represented and the representatives. And basically what we see in the book, and what we see up to the present day, is a real loss of faith in representative government and representative institutions altogether. So basically, what my book shows is the beginnings of the crisis of hegemony of the American elite and its two ruling parties in its inchoate form that really comes powerfully back later.

So I would say those are the two things. But it's interesting. There are two different kinds of criticism of my book. Some people say, "Oh, well, it's too focused on the economy," and other people are like, "It's too focused on culture." And I think if I had to fall on one side or the other, if you look at the introduction, I'm really interested in looking at the economic and material underpinnings of what was going on and the kind of fragmentations of American social classes. I would say what I really wish I had known more about when I wrote the book was, I think, actually Robert Brenner's theories about the stagnation of American capitalism and the intense kind of fratricidal competition in American capitalism—I think those kind of jibe with the story I'm telling in my book, and I've been really interested in the work he's been doing with Dylan Riley since then. So if I had to go back and write it again, I might even make it a little bit more materialist and add in some of that stuff.

Robinson

And sell way fewer copies.

Ganz

Well, that's the other thing. I didn't want to overwhelm readers with a lot of jargon.

Robinson

It's important because people might miss the sort of economic analysis and can get caught up in the very vivid stories of all these people, because you tell it through the stories of people. But it is remarkable when you go back and look at the Perot campaign. It was funny what you were saying earlier about trying to get people interested in this story, and no one's interested in hearing about the Perot campaign. But then people forget how successful he was. And then when you break down all his rhetoric about the failure of the two-party system—"we need an action, we need a businessman"—you think, actually, there's a lesson here that should have been heeded when this guy got—I forget what percentage of the vote he got.

Ganz

He almost got 20 percent. I think he gets 18.9 or 19.5 or something like that.

Robinson

He's the most successful third-party candidate, at least in the decades that I've been alive.

Ganz

He's the most successful since Teddy Roosevelt's Bull Moose run.

Robinson

Yes, worth examining.

Ganz

For sure, yes. He showed a lot of dissatisfaction with both parties. He had a bunch of pretty vague and contentless ideas about reform that were kind of partially technocratic, partially populist, and leaned very heavily on his success as a businessman, which, by the way, as I try to show, was based very much on kind of ripping off and having very close relations with the federal government and being a kind of political capitalist, if you will. So, yes, he really struck me when I wrote the book as a precursor to Trump and Trumpism. And of course, Trump tried to run on the Reform Party line when he made his first attempts and stabs in politics.

But what I didn't realize when I was writing the book is how he was a tech billionaire and how much he reminds me a lot of Elon Musk. His kind of attacks on bureaucracy and his sort of nonsense about reforming things and cutting waste and fraud, and also his demagogy and his belief—again, Perot proposes "electronic town halls," and the people would directly use this sort of applause meter to register their beliefs about a certain policy, and this would be the way things would go. And it sounds like direct democracy, but it's really kind of electronic plebiscites, and it really is reminiscent of the way that Musk has tried to use Twitter to create these artificial publics that give the impression of mass support for his ideas.

So that was kind of—I wouldn't say lucky—but a weird, fortuitous thing that developed where I was like, Musk and Perot are kind of alike. And he even said so on the Joe Rogan show. He was like, Oh yes, he was right about a lot of stuff. Now, who knows what he really remembers about him?

Robinson

Now, that's a very strong case there, I think, for studying and autopsying the Perot campaign. Why do you think it's valuable to look at these kinds of quite fringe figures like The Washington Times columnist Samuel Francis?

Ganz

Well, first of all, if you look at what the people on the right are reading and citing, Sam Francis is one of the guys, and if you look at his idea of what America should be, it's Trumpism. It's a white nationalist republic with a dictatorial chief who has an aggressive foreign policy. It has a protectionist ethos to help industry. It's got exclusion towards immigrants, and it is a real effort to kind of undo what he calls globalism, which is basically the consensus about the world since the end of the war, which was that we were better served by having multilateral institutions and having an ethic that, even though it's hypocritical, tries to resolve things and looks towards world peace as an ultimate horizon. He thinks that's all nonsense. It's cosmopolitan garbage. It needs to be replaced with assertive American nationalism. And he wants to destroy the power of the globalist class, their universities, their media empire, and so on and so forth, and use the power of the state to do that.

So you can't read his writing and not kind of have this, again, eerie feeling that he's really imagining these things beforehand. But it's much simpler than that, than just kind of a metaphysical repetition. The fact of the matter is, the people staffing Trump, the intellectuals on the right, have all read Sam Francis and are into him and will say so if you read what they write.

Robinson

This is more a comment than a question. But one of the things I noticed reading the book is that in this period of time, there is essentially no left. You note that Bush, Clinton, and Perot seem to agree on a lot of stuff. And you can search this book, which is pretty exhaustive on the political history of this moment, in vain for anything resembling a socialist or a social democrat.

Ganz

Well, maybe I gave that a little bit short shrift, because I will note that part of this populist wave that I outline did have other features. So Bernie Sanders is elected to his first statewide office, so you have little hints of it. And then just prior to this era is Jesse Jackson, which is a real multiracial social democratic campaign. You see repetitions of that in AOC, Zohran Mamdani, and Bernie Sanders. So there is a left story here. But I would say in the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union, the left is pretty quiet, and some form of liberalism, whether right or left, seems ascendant.

But the point of my book is actually that liberalism was quite fragile, and its cracks were becoming apparent even then. But I think again, my fixation, my interest in the book, was definitely on the right, and I'm sure there was an interesting story to tell about the American left in the period. And I think there's a very interesting story to tell about Jesse Jackson's campaigns as a precursor to many things that we're seeing now. So, yes, I would love to read that book. I think that the cool thing about writing about this era is it's just coming to the attention of historians.

Robinson

Right. You were able to tread new ground here. Finally, just to conclude, you and I, I'm sure, both share a deep horror at the second Trump administration and what's unfolding in front of us. Are there lessons that come from this time as to how these forces of radical reaction can be beaten back and defeated?

Ganz

That's a tough one. I'm not sure if it lends those lessons exactly. I do believe a more important lesson I hope people heed in the aftermath of this—which, by the way, I'm pretty confident at this point that many more horrible things will happen—but I think American democracy will survive this and maybe even could be stronger in the end. I do think it's important not to allow things to be forgotten.

My experience writing this book was just that these were real warning signs of something dire; something was seriously wrong in the country, and it was sort of papered over. And the kinds of policies, the kinds of real rethinking about how America's economy works, about how Americans relate to each other, and about our culture—these things were sort of ignored once we had another bubble.

So there's a possibility that good times are in our future, and we have another era of good feelings, and then a lot of the lessons of this period might be forgotten. And now you might say, Well, no, this has been so severe; how could anybody forget it? But I think the problem with America is this constant amnesia we have, and that's the struggle and hope of writing history about it. It's just to remind people that nothing comes out of nowhere, and these things need to be watched carefully and addressed. So I guess my hope is just like, look, there's a chance these things will go dormant again, but they'll come back.

Robinson

Yes, well, any of us on the left who have an interest in history are constantly thinking about the question, how do we keep fascism from coming back and winning? You were saying you feel a little hopeful, and this passage from your Substack struck me because I didn't expect it. You said,

"I have to say that the reality of the past decade or so has been much less dark than I envisioned, even as what approaches its outlines, and I think I glimpsed the abyss again."

But you say, "I did not foresee the resilience and the goodness of the American people, how they would fight hard for their freedoms and their neighbors, how they'd sacrifice their safety and comfort for those causes. I did not imagine the Americans could be so enraged by the murder of one man as to take to the streets in the millions."

That is quite encouraging, isn't it?

Ganz

Yes. Look, when this era began and I saw the kinds of political forces that were mustering on the right, your imagination always misses things, and I imagined them having no opposition or pushback, or their opposition or pushback being weak. So I just imagine the worst-case scenario instantly happening: a total disintegration of American society. But I have to say, the amount of people who are really committed to basic ideals that I think are very good in our country, although we don't live up to them, has surprised me. And I'm also disappointed, often and bitterly disappointed, that people or institutions that I thought could be expected to behave in somewhat decent ways don't. But the opposite happens too, where I'm mostly just surprised that people or institutions that I assumed were hopeless show signs of life.

So, I don't know. I think that I have imagined things being worse because I could not imagine that many, many people shared my sentiments of being horrified and disgusted by all this stuff.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.