We Need Solidarity Now More Than Ever

Leah Hunt-Hendrix on why the concept of solidarity needs a central place in political philosophy.

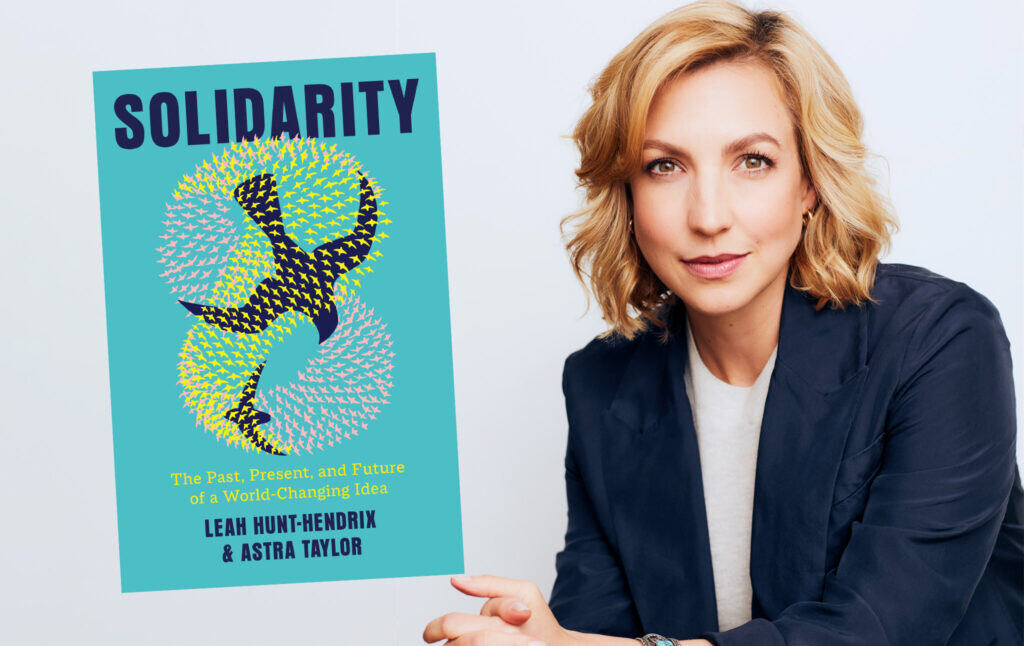

Political philosophy is full of talk about liberty and justice. But in Solidarity: The Past, Present, and Future of a World-Changing Idea, Leah Hunt-Hendrix and Astra Taylor argue that another concept is just as crucial when we consider how society ought to be ordered and what we owe one another: solidarity. A solidaristic ethic means seeing other people’s fates as intertwined with your own and being committed to fighting for the interests of those whose problems you do not necessarily share. It has underpinned the socialist project from Eugene Debs to Bernie Sanders, and as Hunt-Hendrix and Taylor show in the book, it has deep historical roots. They trace the origins of the idea of solidarity, showing how it evolved as a crucial part of left thought and practice, and argue that what we need today is a reinvigorated commitment to it. They explain what it would mean to practice it and the demands it makes of us. In this interview, Leah Hunt-Hendrix shows us the history of solidarity and what it means.

NATHAN J. ROBINSON

In this book, you point out something that I hadn’t noticed before, which is that the concepts of justice, of democracy—or fairness, equality, or liberty—have a voluminous academic literature on them. But the concept of solidarity, while equally important, is not discussed as often.

LEAH HUNT-HENDRIX

Exactly. Solidarity is always thrown around—people sign their emails “in solidarity.” I got such an email today. But in the stacks of the bookshelves in the libraries, there’s very, very little about it. And so, I started to wonder, why has this concept been neglected? The French motto of the revolution was “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity.” I found an article that traced it back to ancient Rome, where it was a concept of mutually held debts and solidarity debts. From there, it was translated when the French adopted some of Roman law through the Napoleonic codes; it got transferred into French legal thought. From there, almost by analogy, it got transferred into the political discourse that we have debts to each other. And so, we should perhaps pay taxes and have some kind of social insurance and public goods because we owe this to each other—we owe it to the future generations, and we’ve inherited so much from past generations. This notion of collective debts, and solidarity being our repayment of those debts, became actually part of the founding of the welfare state and part of the justification for that. This is such a rich history, yet it’s so under-discussed. We felt it was worth spending some time to just recover that history.

ROBINSON

It’s incredible. In the book, you write that in the 19th century, this concept really flourished. This was used by many people, to the point where—I love this quote—“The concept of solidarity became as ubiquitous as smokestacks and steamships in the 19th century.” And you quote a French writer in 1914: “Now these days, not a book, a newspaper, a meeting, a dress, or a formal speech is given in which the word solidarity is not repeated.” So, this idea, at one point, really flourished.

HUNT-HENDRIX

Yes, it did. There was even a group called the Solidarists—almost a political group—and they were part of organizing towards the welfare state. Émile Durkheim was part of that. He wrote a book on the division of labor in society in which he breaks down his concept of solidarity. The big question at the time of the Industrial Revolution, when the grip of the Church was being challenged, was, What can hold us together with the decline of God and King? Durkheim optimistically believed that maybe the division of labor, art, and the interdependence of each of us making up a different widget in the factory would somehow hold us together, or make it clear that we were interdependent and had duties to each other. And over the course of his life, he became less optimistic about that. But that was the question at the time. And solidarity was raised as a potential solution. Perhaps we needed to construct solidarity in new ways given the decline of these previous systems.

ROBINSON

Help us better understand what this idea is. You mentioned this idea of a collective debt and a kind of interdependence. As I understand from reading your book, it’s also a concept that stands in contrast to ideas that divide human beings into groups: racism, hierarchy, nationalism, individualism. Solidarity is the counterpoint to these.

HUNT-HENDRIX

Well, I think solidarity in its most basic sense is a neutral term. It’s just the way a group holds together. It can be positive or negative. There’s reactionary solidarity—based on shared race, ruling class solidarity, white supremacist solidarity—versus what we call transformative solidarity, which is trying to extend the bounds of a collective identity to be broader and more inclusive. In a historical philosophical tradition, we lay out the idea of solidarity being about creating a collectivity that has some difference within it. It’s not unity, necessarily. So yes, it’s always doing the work of creating new collectivities, but those can be more exclusionary or more inclusive.

ROBINSON

You survey the history of solidarity in practice across various movements from abolitionism to anticolonial struggles to the U.S. labor movement. But as you’ve mentioned, there is a kind of solidarity in nationalism. It’s the idea that I see my fate as bound up with those that I consider to be in my particular group. You distinguish that from the idea of transformative solidarity, which is embodied in activist movements. What are the characteristics of activist groups that give them the quality of transformative solidarity?

HUNT-HENDRIX

I probably got my real start in activism during Occupy Wall Street. That’s actually where Astra and I met as well. Occupy was this wild eruption that had a focus on class inequality. It had a really interesting framework of the 99 percent versus the 1 percent. It was a really intentional construction of collective identity, saying that 99 percent of us have something in common, and the 1 percent are those we don’t have a lot in common with. So, it invited people to come together across all sorts of different professional, racial, and national backgrounds and to see themselves as unified and part of a shared political project.

ROBINSON

This is striking when you think back to Occupy Wall Street. Obviously, they were so successful in getting that slogan, the 99 percent versus the 1 percent, into the discourse. We take it for granted. You hear something enough times, and it loses its sense of being remarkable. When you go back and draw attention to it, you think about what it means in a country where we are so politically and economically divided. To say, let’s have the largest possible group of people who have a shared interest, work together—it really is quite powerful. Your book tries to tease out what this means as an idea. But I think many people very much experience this as just a feeling that you know when you feel it, and if you really feel it, it can send chills down your spine. I felt it with Occupy Wall Street. I felt it again with Bernie. You quote Sanders saying, Fight for someone you don’t know, and fight for someone who doesn’t have the same problems that you do. You feel this powerful sense of solidarity with them.

HUNT-HENDRIX

There is something incredibly powerful about collective action. Especially in a society that’s so focused on the individual, on celebrity, or on the social media influencer or the individual entrepreneur, it’s rare that we get to really feel that effervescence of taking action together. It’s so powerful. Of course, nationalism also has that element to it. There can be that kind of nationalist, patriotic effervescence, and it can lead people to war and is often stoked by creating an “other.” Benedict Anderson, someone that we drew on also in the book, has written about nationalism. How is it that we all feel American? We don’t know each other. What do we have in common? National identity is something that’s created and sustained through different practices and rituals, things that are very mundane, like going to the DMV or getting your driver’s license, but also through media. He talks a lot about the role of the media in creating a sense of national identity. That’s one of our real challenges today. Our media landscape is so divisive as opposed to unifying. Nationalism is not the thing we’re trying to lift up here, but people do need to feel like they’re a part of some kind of collective project.

ROBINSON

This idea of seeing yourself as having a shared interest with other people, even if their struggle is not exactly your own, has been really important in some of the most powerful movements in history. You go back to abolitionism and look at people like John Brown, who was obviously not enslaved himself. You cite Friedrich Engels, who came from wealth and was the son of a factory owner. Why did he need to be involved in the struggle for socialism when it wasn’t going to benefit him financially? In fact, Engels subsidized Karl Marx. These were people who felt a strong sense of identification with others, an interdependence to where they had to act, regardless of whether it was going to bring immediate personal benefit to them.

Let’s talk about problems with philanthropy. You go through the history of Rockefeller and Carnegie and all these people who believe on some level that they want to improve the lives of others but who lack what you describe as solidarity. How is solidarity different from those other approaches that still profess to want to elevate and help people?

HUNT-HENDRIX

We call those the semblances of solidarity: things like altruism, charity, benevolence. Even the word benevolence, like goodwill, is one person’s will towards another. One very prominent movement these days is called Effective Altruism. The concept of altruism is about your moral purity, in a way, whereas solidarity is really relational; it’s about both people being active agents and protagonists, not one person being the donor and the other the recipient. So, there’s a way in which philanthropy can be dominating and can really impose the will of the philanthropist on the recipient. In my early experience in this field, I would notice funders would offer a grant to an organization on the condition that they use it for a certain project. And the organization would quietly say, that’s not really what we wanted to do, or that actually pulls us away from our core work, and it could have the power to change the mission of the organization. We are in a situation where most nonprofit organizations need funding.

ROBINSON

You’re making a distinction: what kinds of support are you giving to people, and are you approaching people as equals? That seems to be a really important part of solidarity. Do we all feel bound together with everyone contributing?

HUNT-HENDRIX

And see our fates as intertwined. The effective altruists may send malaria nets to countries in Africa, but they aren’t necessarily concerned with the dynamics that created the situation where malaria continues to exist in Africa but not here. What, potentially, was the United States’ role in that? There’s a real absence of politics, power, and history, and just a sense that I have these resources now, and I can give them away. But the recipient is not seen as an agent who has decision-making power or political agency.

ROBINSON

As I mentioned earlier, you define and theorize solidarity in the book, but it is one of those things where you know it when you see it, and it’s best understood through seeing examples of it in action. We’re recording this just a few days after the young Air Force member Aaron Bushnell self-immolated in front of the Israeli embassy to protest the Gaza genocide. Obviously, that’s an extreme step to take. As I was reading your book, I was thinking about this guy. He’s not Palestinian, and I don’t know that he has Palestinian relatives, but he is a person who saw himself, his fate, as bound up with whatever happens to Gaza. He saw himself as complicit—he said he felt complicit—and said he had a debt. It’s a rare person who feels that way, but that does seem to be the core of what solidarity is.

HUNT-HENDRDIX

Yes, exactly. I think that we are all complicit in the actions of our government, and our government is currently funding Israel’s war on Gaza. There are many, many people, Jewish Americans and Jewish Israelis, who have expressed real solidarity and are doing so much to try to bring about a ceasefire.

ROBINSON

In some ways, you are thinking of solidarity as the antithesis of self-interest and individualism. But on the other hand, there is a way in which solidarity is in our self-interest. With the Bernie Sanders campaign, with everyone coming together to work on a vision of what we could achieve together, it’s true that people were fighting for people they didn’t know—even if you don’t have student debt, you believed that student debt was an injustice. It was also true that in a country with people as lonely and atomized as this one, even if you didn’t have the particular problems that were being addressed by the public policy, being part of a solidaristic movement just totally transforms your life. You meet and get to know people, you have experiences you never would have had, and you don’t sit alone scrolling through the news.

HUNT-HENDRIX

I think there is a real aspect of self-interest to solidarity. Political philosopher Danielle Allen talks about rivalist self-interest versus equitable self-interest. Rivalist self-interest is very focused on competition and zero-sum, but equitable self-interest is the way in which we all benefit from each other benefiting. So, I’d benefit from having a community that is healthy, safe, and thriving. The idea is that we lift all boats, but you see yourself in the boat as well.

ROBINSON

We’ve talked about how activist movements succeed through transformative solidarity. But I want to talk about a couple of the implications. You do challenge readers by saying that on the Left we need to be careful about the tendency to call out, denounce, and cast people out of our movements for their transgressions. Obviously, you have to have your lines of who you will and won’t have in your movement. But an organizing and solidaristic approach requires a great deal of empathy. You challenge social justice movements and progressive activists to make sure that the idea of solidarity is real. It’s not just a word, but it’s also not necessarily easy to show solidarity.

HUNT-HENDRIX

We definitely need accountability and to have lines and to help people change when they cross those lines, but I think our movements can be quick to be exclusive. The Left can tend to self-marginalize and just feel unapproachable. Personally, I was raised Evangelical, and I recently went back to visit my parents in Dallas. We went to church, and right when we walked in the door, there were greeters just pulling you in and telling you about all the things that you could sign up for—this singles group, the men’s group, the parents group—and it was very welcoming. I don’t endorse their theology, philosophy, or politics, but I think there’s something to learn from that. Also, I think a lot of people on the Left struggle with burnout after being in the movement for a while because the standards are high and the work is long. How do we become a movement that is nourishing and healing and rejuvenating and makes people want to come back for more? That’s the challenge.

ROBINSON

I recently wrote an article about the 1930s New Masses magazine. It was incredible. They used to have things like the socialist dance nights, book clubs, and all sorts of things to bring people in.

In the book’s conclusion, you talk about the virtues that accompany solidarity. You say that solidarity should require us to look within ourselves and think about who we are and to try and embody these virtues that you list. Could you tell us a little bit more about that?

HUNT-HENDRIX

I’m sure many of your listeners and readers think about how they might become better writers, better athletes, better at whatever they want to pursue. So I think we all do understand that it takes work to cultivate different skills and sensibilities, and I think that’s also true of our moral sensibilities, about how we treat each other, and the kind of people we are in the world.

Part of what society does is to cultivate certain kinds of people. Capitalism cultivates us as consumers. We need to be aware of that and realize that we have some control over what qualities we cultivate in ourselves. Things like humility, hospitality, and courage are things we want to try to intentionally foster.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.