Steven Thrasher on Campus Protests and The Viral Underclass

The journalism professor on what he saw at Columbia and what viruses and crises illuminate about the structure of society.

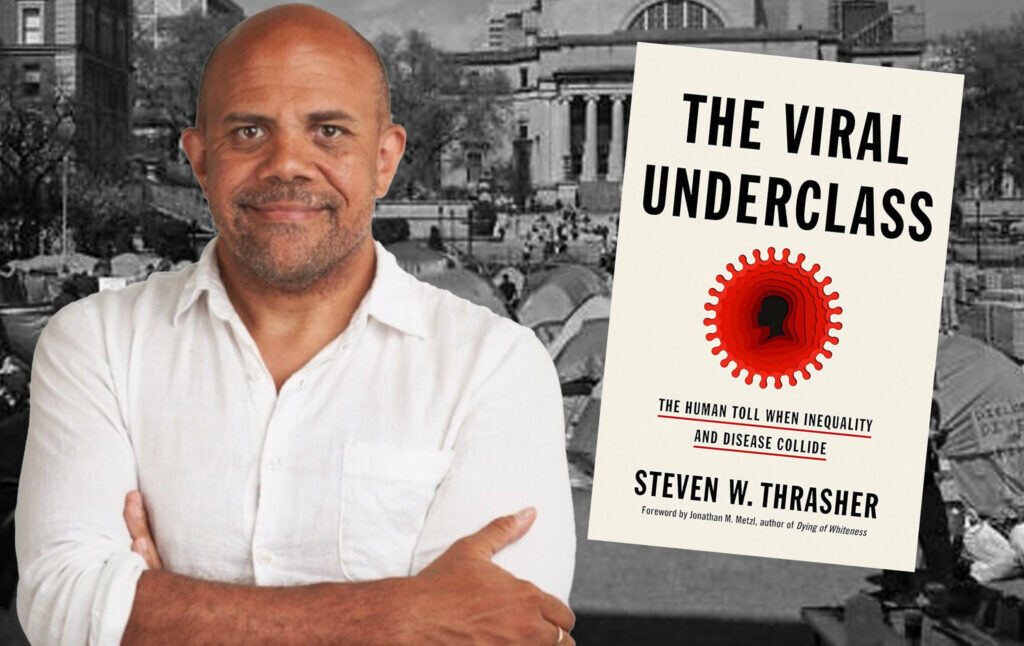

Steven Thrasher is a professor of journalism at Northwestern University and the author of The Viral Underclass: The Human Toll When Inequality and Disease Collide. He was also present at the Columbia protests over Gaza. He joined us recently on the Current Affairs podcast to discuss what he saw at the protests, before moving on to discuss his concept of the "viral underclass," tracing how inequality and disease interact, from the AIDS crisis to COVID-19. An excerpt from this interview was played in our recent audio documentary on the Gaza protests. Prof. Thrasher's LitHub essay on the protests is here.

Nathan J. Robinson

Before we get to the subject of your book, let's talk about Columbia University because you were there recently. This has been one of the biggest things going on in the country. You talked about what you saw recently on Twitter, and I really liked it because you had a totally different or challenging narrative. I think these things are often portrayed in the press as unruly and angry, but you portrayed it as beautiful and inspiring. Could you tell us about that?

Steven Thrasher

Thank you. Also, it was unusual for a journalist to actually report from the place that it was happening. I did find it really beautiful. I had gotten onto the campus—the Columbia campus is quite large, and you could avoid this entirely if you wanted to—but what I saw was really quite beautiful. The first thing that drew me into the Gaza solidarity camp was I saw a young woman really defuse the situation between a couple of Zionist students very effectively. When I was congratulating her on how deftly she had brought the temperature down on the situation, she actually invited me to come on to the lawn where it was only students, or mostly students, and people they invited on. It was really beautiful to see the way that they were experimenting with creating a different kind of society.

It's a dynamic I've seen in different kinds of protests I've covered over the years—Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter protests—where people are responding to something really horrific by trying to create the conditions of a different kind of society, by distributing food and entertaining and educating one another. As a print journalist myself, or a person with a history of print journalism, it was very touching and funny to see the Columbia Daily Spectator get passed out, almost like in a movie, with people racing to read it and sitting down to read it once they got it, and the same thing with the New York War Crimes, a parody of The New York Times, and The Indypendent that were being passed out.

And then there was this teach-in with Norman Finkelstein, which was everything that right-wing provocateurs say that they want, in some ways, in a dialogue. He does not like the phrase “from the river to the sea,” but they had this extremely productive and respectful conversation and questioning about that. There was also a really touching speech by a nurse who just returned from Gaza, bringing greetings from the people of Gaza and sharing some of the horrors he had seen, and then ended with a woman, I believe in her 70s, who had been arrested in the same spot in 1968, and wished the students well.

It was really beautiful to see how during the Muslim prayers—the Muslim students while they were praying—other students surrounded them so they could have some privacy. And then there was also a Shabbat happening with Jewish students. I was there on Friday, so it was at sundown, and I think it was a regular Friday Seder dinner. I've since read that there has also been a Passover Seder dinner that's happened in that space. It was really touching to see them working together to think differently and really create critical pedagogy, a political dialectic about the situations they were facing, and a real creativity to try to force the university to divest, but also to apply the things they're learning in class to a mini-society they were making. I found it very beautiful and not threatening at all.

Robinson

I recently interviewed Leah Hunt-Hendrix, one of the authors of a new book called Solidarity that's about the ethic and philosophy of solidarity, a notion captured in what Bernie Sanders said about "fighting for someone you don't know." And one of the interesting things the book points out about solidarity is that it involves acting on behalf of people whose immediate problems you don't necessarily share personally.

And one of the incredible things about the Palestine protests here is that they are Palestine protests. Palestinians, in the United States and the U.S. political culture, have been variously neglected, despised, and portrayed as terrorists. And you see these young people coming out—people most of whom likely will never go to Gaza or the West Bank and see these things firsthand—and they are willing to get arrested and risk their careers. Columbia students are now getting suspended, and they're doing it on behalf of people that they've never necessarily met.

Thrasher

Yes, and that was a really touching point, actually, that Finkelstein made. Many of us have connections to Gaza—I have Palestinian cousins, and many people there, I think, have Palestinian family. But one of the points Finkelstein laid out historically is that in the 1960s, there were people who did have an ethical claim about Vietnam as well, but they also had some level of self-interest for not wanting to be drafted, and that there was this very direct connection to what was happening in the United States, versus with the Gaza situation, as you said, there is no direct benefit.

In fact, most people who are protesting are putting themselves greatly in the crosshairs of huge potential professional and financial harm—all kinds of social harms and ostracization that could happen politically throughout the rest of their lives. So, it is really touching to see people stand up for the people that they don't necessarily have a direct benefit from standing up for. I also got to briefly go into the journalism school where in Pulitzer Hall, a former student from my school, Yasmeen Altaji, had set up a memorial for all the journalists who've been killed in Gaza, Israel, and in Lebanon, and it's more than 100 journalists. One-time journalists, and still sometimes journalists like myself, too, standing up for Palestinian journalists is the right thing to do. But I think in this climate, from what we've seen from a lot of mainstream journalism, is it can cause problems for you.

I am so grateful to these journalists because they have modeled a really different form of journalism that's really rooted in solidarity and communal care and understanding of one's own subjectivity, but that still means you can do valuable reporting. You see many of the journalists who are still alive—the ones who either have not fled or who have managed somehow to not be killed—doing solidarity work in terms of feeding other people, doubling as medics, and helping in emergency situations. There's a lot that I think is applicable from Palestinian journalists to those of us who are journalists, but a lot of those lessons are also being taken to heart and executed by the students at Columbia. And so, you see them creating general assemblies and creating publications, and it was really quite beautiful to see. It's so different from the handwringing that you see from people who haven't been there.

Robinson

That memorial that you posted a picture of there in Pulitzer Hall that has been assembled is really very moving, but it's very disturbing because of just how many Palestinian journalists there are on that wall. You see these journalists in the press vests, with their cameras, doing their job. But as you also pointed out in your thread, emerging young journalists at the school are going to see this and these people and realize this is what it means to be committed to the practice. It's so important to see these journalists who have been killed. You're not going to see them elsewhere because the profession has failed in many ways. You're not going to see these pictures unless someone puts them up on the wall.

Thrasher

That's unfortunately true.

Robinson

It strikes me from what you're describing of what I saw some of the Occupy encampments back in 2010-2011. It had that same thing, that feeling that it wasn't just a protest, but also the creation of something more, that's very difficult to describe. It sort of broke through the atomization, the loneliness, the depoliticization that characterizes our society, where people are often isolated—they're in their dorms, on their own, and on their social media feeds. It brings them together in a place and something incredible happens. It's a little difficult to describe if you haven't seen it firsthand.

Thrasher

I spent a lot of time in Zuccotti Park and different occupations around the country. I have more language about that now than I had at the time. There’s this phrase “third spaces” that people feel like are going away. These are spaces where you can just actually see other human beings without having to buy something. To me, it's the most akin to having grown up in church. Unfortunately, it has since burned down, but I long went to a church when I lived in New York City that did a lot of social justice work, and I thought about that as more of my social life has become mediated through social media, and also during COVID, that so many of our human relations end up having to be planned and sometimes planned with some exactitude. Especially when you live in a place like New York, where every inch feels like it's financialized.

During COVID, a lot of people became psychologically aware of having passive relationships with people and how valuable they are, whether it's a clerk that you talk to in a store, or people that you see in your gym, or someplace where you don't necessarily think they're your best friend, but once that was taken away during COVID, you realize, I really got a lot out of these interactions that didn't have to be planned, with certain moments of the day with other people through the waters of life, and people really love that.

I realized in Zuccotti Park that people love having a place where they can just show up and have conversation with other people. They like feeling that their lives have a sense of meaning. As we saw with 20-25 million people coming out in the summer of 2020 around George Floyd, people do like coming together to step up for things that they think are wrong, and having a physical place to do that. All of them have similar elements. They're all feeding people—there's always some kind of communal kitchen. I didn't see this at Columbia, but in almost every other occupation I've been to, some kind of library emerges, or some kind of free store where people can get the things that they need. People like being in community with one another, and you can really feel the forces of the ruling class trying to make that seem disgusting—

Robinson

That's why it must be destroyed.

Thrasher

Yes, that's why it has to be destroyed. People can't be feeling solidarity with one another. But at some level, I spent a lot of time at the library at Occupy Wall Street, and it was just amazing seeing how many people wanted to just come in, see books, and talk about books. The other formal version of this kind of thing is at the New York City Library, and half of its weekend hours have now been closed because they have to spend more money on police. But libraries, for the wonderful things that they do, are not usually so much about talking. People really like having a place that's not a bar, or someplace where if they buy something, they can just show up and hang out with other people. It's a beautiful thing to see. Because, as you said, it strips away many of the feelings of alienation that people have in a way that's quite beautiful to witness and be a part of.

Robinson

I liked your thread because it shows that it's about more than Palestine. It's also providing a vision of solidarity in a community. And as you mentioned, it's funny because the Right hates the radical professor undermining classical education, but Norman Finkelstein is such an interesting kind of anachronism. He's got a very old school view of education, very Socratic: we're going to go through the old texts; we're going to get out our John Stuart Mill; we're going to play devil's advocate and interrogate all of those ideas—everything they say that education should be like is what he does. But he makes you think.

Thrasher

I had this moment where I was sitting on the grass. I wasn't that far back from him, and he's standing in front of me, and behind him, it says, Cicero, Shakespeare, Socrates, and all these names of the Western Academy on this classical building. And then you have all these students, many in hijabs—many Muslim students and students of different faiths—who are listening to him. I could tell from some of the side conversations that they really didn’t agree with some of the things he was saying, but they had this very sort of old school Socratic conversation and disagreement, in the ways that you would think the people always screaming about cancel culture would be happy about, that this exchange is actually happening and exactly the way that they think it should happen. It doesn't mean they don't disagree with each other. But it was, to me, one of the most interesting pedagogical experiences I've had.

Robinson

I do want to get to the subject of your book, The Viral Underclass: The Human Toll When Inequality and Disease Collide. One of the things that your book shows us is that in moments of crisis, you really see a society's values come out, and everything gets magnified. Things that might be operating in the background that are easy to ignore become less easy to ignore. The riot police come out, and you think, that was always waiting to come out the moment this was challenged. You reposted this tweet that someone put out when Columbia had gone to remote learning, that to disrupt the protests, of course, they'll do remote learning, but for COVID, that's controversial. It shows what our values are; it shows who we care about and how much we care about them. So, I would love if you could introduce first your idea of the viral underclass that underpins everything in this book.

Thrasher

The "viral underclass" is a phrase that was coined originally by an activist named Sean Strub, and he was using it to talk about something that I had been writing about as a reporter for many years when I first connected with Sean. He was explicitly talking about the criminalization of HIV. It's been declining—it used to be about 30 states, and now it's in about 20 states in the United States—but you can be prosecuted for either transmitting HIV to another person or even engaging in activity where it literally cannot be transmitted. Some "Blue Lives Matter" laws recently have added an HIV component where they've said if you spit while you're being arrested by a police officer, you can be arrested for attempted murder of that police officer, even though HIV does not even move through saliva, but that's the way that the law operates.

And so, Sean used it to talk in a very kind of class way that originally was used to talk about infants: if an infant is born with HIV, they're going to be living under a different set of laws for their whole life than somebody who's not living with HIV. We have had laws in our country that are explicitly based on what we call immutable characteristics. There have been laws that are very explicitly about Blackness. But for the most part, the reason why critical race theory is important is that while laws may be read as colorblind, they have a particular effect on a certain population. But that's not the case with HIV laws. They explicitly say, if you're living with HIV, you're going to be under this different standard.

And so, that's how Sean used that phrase. When I was doing my reporting, I started hearing activists using it differently when they were talking about whether HIV law should be abolished, or whether they should be updated with current science. The updating would mean that you would take out laws like those Blue Lives Matter laws, or for somebody who was taking an HIV prevention medication called PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis), you wouldn't get prosecuted, or if you're HIV positive and taking your HIV medication, you also cannot transmit HIV as well. It so suppresses the virus and defangs it that it can't go from one person to another, and that's determined by something called a viral load—you have a very low viral load. People may have heard this term with COVID—high or low viral load. But they said that would create yet another viral underclass if you were applying these laws to people who did have a high or low viral load, because the people who are most likely to not have HIV medication are Black, incarcerated, or homeless people who are affected by all these different social vectors.

I kind of use viral underclass in a third way: I think of it as an analytic to look at why certain people become infected with viruses, and why they're likely to have disparate health impacts from those. They're all the structural factors that happen before somebody becomes infected with a virus and whether that virus will be something they can manage, eradicate, or are going to die from. And I started trying to use this analytic at the beginning of COVID because I could see the same maps I had been looking at HIV for many years were becoming the COVID maps. And it was, in a way, strange to me because they're very different viruses in terms of their biological characteristics. They transmit differently and have different properties, and it’s similar with Mpox (Monkeypox, or MPX) as well. HIV is a retrovirus, COVID is a respiratory virus, and MPX is an orthopoxvirus, but you can see the same maps of where there are emerging in different places. Sometimes that would make sense. For COVID or influenza—those are both respiratory viruses—it makes sense that for places with bad ventilation that you would see it.

But I theorize that a viral underclass helps us see how all these different social factors, two of the biggest in the U.S. being homelessness and incarceration, create these conditions, where not only do people become infected with viruses, but they have so many predetermined matters of their health that they're not only more likely to get the virus, but the virus is likely to do great harm in their body, and unfortunately, perhaps make them die. And that's where I think a viral underclass helps us see that it's the underclass part of it rather than the particularities of the virus itself that make these determinations.

Robinson

And so, a law can be neutrally applied, but if it is enforced in a situation with preexisting structural inequalities, the application of the law becomes unequal and punishes a particular class. The classic idea is that it's illegal for both the rich and the poor to sleep under bridges. A virus is also something that, as you noted, doesn't discriminate—viruses flourish in the human body, and it doesn't matter which human body—but everything depends on what situation the virus is being introduced into. And what we see is that same kind of thing where a "neutral" punishment becomes highly unequally distributed when you have a class system and a racial hierarchy.

Thrasher

Right now, we're in a position, as the Biden White House put it quite crudely, that the COVID tools have been moved into the marketplace—they've moved from the public sphere into a private marketplace. We're already starting to see these patterns, and I think we're going to see them continue much more so. Say there's a person who gets an annual physical, and that annual physical could include their doctor giving them a flu shot, and now also a COVID shot. And so, a pattern emerges of who's getting vaccinated regularly, and are the other people in their household more likely to be getting vaccinated or to be getting vaccinated regularly as well? We've seen for many years with influenza that there are racial and class politics around this. When people actually get it, they can sometimes fare similarly to other people, but there are other pre-determinants of health that inform that, too, even just at the level of who's getting vaccines or not.

So, if you don't have health insurance, you're less likely to be getting COVID boosters regularly. We did have this brief period of semi-socialized medicine where anyone in the United States could show up and get the medical care they needed without fear of a huge bill or having to pay at the point of service. As a matter of public health, we've known for decades around the world that the way to get people into public health campaigns is no charge at the point of service. You go to them where they are, you establish a relationship with people over time, and you don't only deal with the sort of crisis that's right in front of you—you deal with the person as a whole person who's going to have a range of health needs. And so, we had this very brief period of time when people could get their needs met around COVID. That was an infrastructure that we could have continued to build upon, but it was radically deconstructed very quickly. It was a one and done deal. And I started seeing how terrible that was when this MPX or monkeypox outbreak started to happen, primarily among men who have sex with men, in the summer of 2022. We started seeing incidents of it in Europe in the spring of that year, and knew it was going to become a problem in the United States. And unfortunately, the U.S. had just had an apparatus where we were giving out 4 million shots a day for COVID that was being dismantled.

Now, had that infrastructure been maintained in any kind of way, the U.S. could have said, we need to have some form of this infrastructure through which we can give annual flu shots, and if there's a meningitis, hepatitis, or MPX outbreak somewhere, we have this infrastructure. But it was just very quickly stripped away as if it had never existed, and had to be cobbled together through a lot of volunteer work by the communities that were affected. And so, the people who have access to the infrastructure will be more likely to have better health outcomes. HIV is a very slow-moving virus. Nobody should die from AIDS. It takes 8 to 10, maybe even 15, years from infection for someone to die. And yet, thousands of people still die from it and the United States. I've talked to plenty of clinician friends who work in places like New Orleans in ERs where someone will come in and have AIDS—not just HIV, but full-blown AIDS—and they die within a couple of weeks. At that point, there's very little they can do for them medically, but a big reason why it's gotten so bad is because the person will say they haven't seen a doctor in 10 to 15 years.

And so, the more stuff gets moved into this private marketplace, like COVID, only people who have health insurance and see a doctor once a year can get an annual checkup and get a booster. But those people who have been left out of the general marketplace, of which there are tens of millions of people, they're going to have higher rates of COVID and all these other things.

Robinson

It strikes me that this is a way in which policies can be almost eugenic in the way that they kill the weakest among us. To just briefly come back to Gaza, I saw recently there was a child with cerebral palsy who died and there have been children who have started dying of starvation, and one of the things about those children is that they've often been children with preexisting diseases. But that's the point. With these sorts of things—these crises, these calamities—the people they hit the worst first are the people least well-equipped to deal with it. And so, if you have a grotesquely unfair society with an underclass, the killing is going to fall on—in Gaza in this case—the disabled, and the disabled are the least well able to deal with it. And in the United States, as you point out, viruses hit the poor and are racialized. One of the reasons I'm so glad your book exists, and I want to keep talking about your book as we try and forget about COVID, is that it's just so grotesque when you actually draw out the implications here.

Thrasher

Yes, so much of the stuff that happens with public health is predictable, which makes it seem even more obscene. So, long before October 7, for the past 10–15 years, the highest rate of norovirus in the world for children has been in Gaza. Norovirus is a virus that particularly hits the elderly and children, gives them dysentery, and can dehydrate and kill them. So, of course, that was under the conditions before the last six or seven months, and was already a crisis for children there. There is a horrific Hepatitis A outbreak happening right now in Gaza. And again, it's all predictable. Without access to clean water and clean food, particularly vegetation, this was guaranteed to happen. Something I think about here in the United States, and as I wrote about in the new edition of the paperback, is I'm very hard on the Democrats through it. But I'll start with the red states first and then get to the Democrats. There has been a wave of anti-trans legislation around the country, and that very purposely, I think, creates a viral underclass in a very explicit way.

I write about trans health, and I know many trans people. I'm talking to you right now from the institute at Northwestern University where we do LGBTQ health, and trans people have a pathway to good health. We understand how to support them psychologically, and medically, many people choose to get hormones. Like any other medication, there are very sterile, safe ways for people to get the medications that they need under the supervision of medical supervisors in sterile conditions. When you take away people's hormones and tell them that they're going to be arrested, or their children will be arrested, or parents will be charged with child abuse if they try to help their children get the medication that they need, and they're pushed into a black market, their bodies are being effectively opened up to more viruses because they will be using syringes that we can't source and don't necessarily know are sterile, and that opens up the more likelihood of HIV and hepatitis. When people deal with all the social stigmas and the bad health outcomes of transphobia and various kinds of bigotry, they're going to be less likely to get good jobs that have healthcare, and they will be more likely to end up in the informal economy living without health insurance.

That all but guarantees that they will end up in a viral underclass. And since he's the president right now, and waging a genocide in another country, I have a lot of ire for people like Joe Biden, who helped shepherd through two of, I think, the worst structural acts for public health for Black Americans in the country: the 1994 and 1996 so-called crime and welfare bills. The crime bill made it so that once people had been even just arrested, in some cases for drug related crimes, they were not allowed to live in public housing. Many of them lived in public housing, and they couldn't live with people who are getting public benefits. So, if their family members have public benefits and have this record, they couldn’t live with them. That was one of the driving forces for why homelessness really started to skyrocket for Black Americans starting in the 1990s.

And then, of course, locking people up: not only does putting them in jails make them more likely to become infected with any number of infectious diseases, but once they're in the criminal justice system it makes it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to get a job with health insurance and stable housing. Incarceration and homelessness really started to fuel each other in this horrific cycle, and you can see it when you look at the graphs.

When the CDC started looking at racial disparities between Black and white Americans in 1986, I think, there was about a three-to-one disparity: Black people proportionately were three times more likely than white people to acquire AIDS, not just become HIV positive. By the mid-1990s, when there was an available medication, that disparity went to about six-to-one—it actually grew. When I was writing my dissertation in the first draft of this book, the disparity was about nine-to-one. Black people, 20 years after there was medication available, had higher rates of HIV in the mid-2010s than white people did before there was any medication at all. And so, you can see how it's not actually a matter of who has more sexual partners or what drugs they do, but all of these structural things make it so that the viruses are finding their ways into bodies. It's like a flood: the water will go to the place where it can get in the easiest, and the same thing happens with viruses. We expect the GOP to be homophobic and racist, but the Democrats structurally open up many bodies to viruses in ways that create great harm.

Robinson

Yes, and then that way laws that don't look like they are public health policy choices are still public health policy choices. A crime bill is also a public health policy choice.

Thrasher

Exactly. In the first year of COVID, in 2020, the US had about 4 percent of the world's population. In that first year of COVID, we had 25 percent of COVID cases and 25 percent of COVID deaths, and we also had 25 percent of the world's incarcerated population. These things are not separate from one another; they're very tied to one another. We have an outsize representation of people who are incarcerated, being deported, and are uninsured, and this fuels massive problems with public health, despite the great wealth of this nation.

Robinson

We ran in 2021 an article by Cassandra Greer-Lee, whose husband Nickolas Lee was incarcerated in Cook County Jail in Chicago. She was trying to get in touch with every politician she could and pleading to get them to release her husband, thinking he was going to get COVID in jail. He got COVID in jail, and he died. It's a pretty simple thing: if you keep people in this facility where the virus spreads, they're going to get the virus. A lot of them will die, and a lot of them did. And again, one of the reasons I wanted to talk to you about this book is that I really do think there's this effort to throw COVID in the memory hole, this horrible injustice of people who are essentially murdered by policies—policies made by people. There has been no accountability.

Thrasher

I agree, we are in this very dangerous period of attempted forced amnesia, and you see it all over the place. The gentleman whose name is slipping my mind right now—he lived in an iron lung his whole life, and there was a big feature about him in 2020 or '21 in The Guardian about how afraid people were around him that he would get COVID. He'd been in the iron lung for 70 years, and he eventually died of COVID earlier this year, but The Guardian didn’t even mention it in their story. There are all these ways that we're being keyed to forget about this really horrific thing that happened. The understandable impetus is that it's very painful to think about. But there are all these legacies that could have been quite beautiful from what happened with COVID. We had the opportunity at a new floor. At the level of electoral politics, the Democrats were really horrible in ending not only student debt payments, but also eviction moratoriums and the child tax credit.

Robinson

And the Medicaid thing.

Thrasher

Medicaid expansion. And creating infrastructure for people to get public healthcare they need, particularly in emergencies. And so, in some ways, with both Gaza and COVID, that I feel more gaslit by the Biden people than I did by the Bush people. The Bush people were in power when I was becoming an adult, and when they were lying about the war on terror and everything after 9/11, a certain portion of the media knew they were lying and called them out on that. But now it feels like most of the mainstream media is also either subconsciously suppressing COVID or just acting like it's not a big deal. We've had periods this year when still two to three thousand people a week were dying. The last week I looked at, it was still about 1,200, which is not an insignificant amount. It's a couple hundred people a day. And it was such a painful thing for so many of us that more than a million Americans died—almost everyone in the United States knows people who died.

The myth of American progress is we must always move forward and not look backward. But it's really important to sit with this discomfort, both of the pain we had of people who died and also that there are things we could do to make sure more people don't die. I am shocked from a public health standpoint. I talk to my students, and they're always shocked when I tell them that medical providers did not wear gloves when they worked with you prior to HIV. Your dentist would not wear gloves. I remember being a small child, and if you had your blood drawn or saw a nurse, doctor, or dentist, they just didn't put gloves on. It was a fear of HIV that started the use of gloves and the creation of something called universal precautions, where you just assume everybody has HIV as you deal with them. And there is no reason why the same assumption, at least in healthcare settings, should not be applied to COVID. Surgeons have long worn masks in surgery, and now there's a very good reason why health care providers should be wearing masks and/or there should be real standards around the ventilation of air in health care settings.

And almost as if it's a purposeful, forced amnesia, not only are masks not being used, but I'm constantly hearing reports that places where masks used to be used prior to COVID are not being used anymore, like in cancer words. They're not being used anymore in NICUs. There are reports of construction workers coming in to ERs with sawdust lung issues, and they find out the person was not wearing a mask at work, and they easily would have been five years ago. And so, it's really disturbing to see how much, I think in the name of capitalism and the desire to get everyone back to shopping, not thinking, and back to working in offices under the conditions they were five years ago, and not wanting to spend money on ventilation and these kinds of things, that there's a sustained desire to just forget this thing that happened and move on. It's really sad.

Robinson

One of the things that comes out of your book is that understanding the truth about how viruses work, the impact they have, and how they spread through society, is actually profoundly challenging to certain aspects of the prevailing ideology to defend capitalism. You say in the book a couple of times that viruses have been your greatest teacher, which is a very striking phrase. The virus illuminates so much. And you point out the idea of individualism, the idea of our own grit, hard work, and merit determining our outcomes in life just falls apart when you start to understand just how interconnected everything is. So, I understand why there's almost like a shutting down—we can't think about this too hard—because if we pursue those thoughts too far, they might have radical implications that we don't want to deal with.

Thrasher

Exactly. I'm a gay man, and I owe so much to gay culture. And I've been thinking about this in terms of Gaza, too. I owe so much to gay culture and the gay people who died of AIDS and are still dying of AIDS but who died of AIDS long before me. They created a form of interdependence that has so enriched my life and created an entire gay culture around that as well. A fundamental legacy of groups like ACT UP is that our fates are connected to one other. You can't only worry about whether you have HIV, you also have to worry about whether you're going to transmit to somebody else, and you want the viral load of the whole community to be low. And so, that's why you not only, in the '80s, did things like teach people to use condoms. Now, with this drug called PrEP, which prevents HIV, there's a lot of community education around that. You understand that it's not only your responsibility, but that our fates are really tied to one another.

And the U.S. tapped into a lot of that feeling around COVID, where people realized our fates are connected: the air we breathe defies the idea that each of us are discrete individuals; we are these organic beings that are constantly exchanging organic material with other people. We could think about ourselves not as a group of millions of individuals but as one collective body. And you're right, that's a very dangerous thing that must be shut down by the ruling class. They don't want us thinking about that too much.

And I think that many people have had a sense of that with Gaza as well. Knowing and understanding these people who are far away, what's happening to them and what is being tested on them, could happen to us. There are technologies that are being used there that are being deployed not only by police departments but explicitly by university police departments. At my alma mater, NYU, the campus police had trained with Israel. Many of our campus police departments have gone to Israel to train.

And so, the lack of humanity that's being displayed in Gaza and the way that we are being told by the media and political class that we shouldn't care about those people, the American people understand, miraculously, that we should care about them, even though we're being told that we shouldn’t. And I similarly feel like they're all these lessons that these people are giving us at this enormous sacrifice—the ultimate sacrifice of their very lives—where they're showing us that they are dedicated to one another, they love each other in Gaza, and they refuse to give up on their humanity. We are having the opportunity to learn from that lesson, and to take care of one another in this country.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.