James Lindsay’s “Race Marxism” is Ignorant About Both Race and Marxism

Critical race theory and Marxism are thoroughly and predictably warped in this conservative bestseller.

In 1959, a group of right-wing protestors descended on the State Capitol building in Little Rock, Arkansas, waving placards that said “RACE MIXING IS COMMUNISM.” By “race mixing,” they meant the ongoing efforts to integrate Arkansas public schools, and to dismantle segregation and Jim Crow in the American South. By “communism,” meanwhile, they meant an insidious, creeping evil, straight out of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s fever dreams; the one, supposedly, served as a mask for the other. With this message, the protestors hoped to delegitimize the nascent Civil Rights movement, paint it as anti-American, and stop demands for racial equality in their tracks. Theirs was a blunt, simple slogan, and it frankly expressed the feelings of paranoia and resentment that motivated conservative politics at the time.

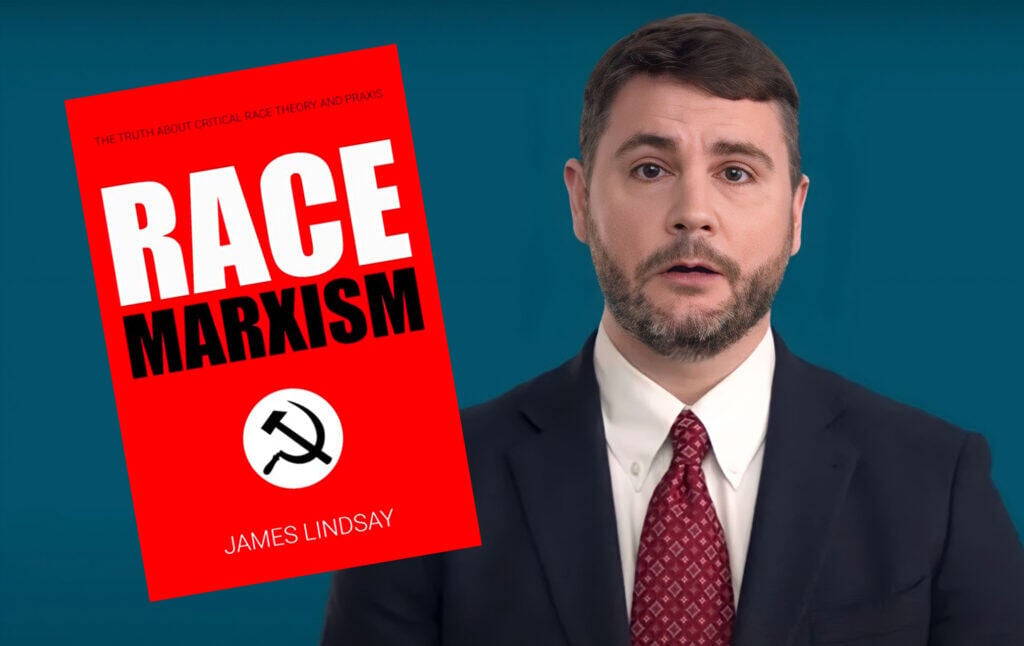

Today, sadly, conservatism hasn’t changed much. In Race Marxism: The Truth About Critical Race Theory and Praxis, author James Lindsay echoes the 1959 sign-wavers, claiming that efforts to address racial injustice in America are really “the tip of a one-hundred-year-long spear that is being thrust into the side of Western civilization.” The culprits, he claims, are the adherents of “cultural and neo-Marxism,” who accuse American society of racism and thus aim to undermine and destroy the country, ushering in a totalitarian “dictatorship of the antiracists.” Lindsay’s thesis may sound ludicrous on its face—and it is—but his book has become a bestseller, racking up hundreds of positive Amazon reviews, and the man himself regularly appears on talk shows like Dr. Phil and The Joe Rogan Experience to expound his views. So it is, regrettably, necessary to examine those views in detail, and see just how detached from reality they are.

As the title suggests, Lindsay’s bête noire is Critical Race Theory, which he (along with fellow activist Christopher Rufo) has helped to popularize as a buzzword on the political Right. Properly speaking, Critical Race Theory is a small but fascinating subfield within academic sociology which examines the way law, economics, and other social institutions are shaped by the concept of race (and all its associated prejudices). As Matt Bruenig has suggested, it would probably make more sense to call it “Critical Race Studies,” since it encompasses several broad “areas of research” rather than a “unified explanation of something.” However, in the hands of people like Lindsay and Rufo, the term “Critical Race Theory” has been expanded to include virtually any discussion of racial injustice, past or present, and is used synonymously with “antiracism.” Increasingly, the concept has been weaponized by Republican politicians like Donald Trump, Ron DeSantis, and Glenn Youngkin, who propose draconian new laws to eliminate “CRT” from schools and other public venues, and by activist groups like Moms for Liberty, who attempt to bully librarians into removing books about racism from their shelves. Around the country, the placards have reappeared, with messages like “CRITICAL RACE THEORY IS COMMUNIST RHETORIC” and “STOP CRT IT’S EVIL MARXIST.” Everything old is new again.

In the first chapter of Race Marxism, Lindsay offers his own definitions of Critical Race Theory:

- Calling everything you want to control “racist” until it is fully under your control.

- A Marxian conflict theory of race; i.e., Race Marxism.

- A belief that racism created by white people for their own benefit is the fundamental organizing principle of society.

Already, there are issues. To support his third definition, Lindsay draws on a 1995 paper called “Toward a Critical Race Theory of Education” by Gloria Ladson-Billings and William F. Tate IV, which he quotes as saying that race should be “the central construct for understanding inequality.” By singling out this six-word snippet— which is used by the authors to describe completely different writers and texts—for mention twelve times throughout the book, Lindsay attempts to paint practitioners of Critical Race Theory, and people concerned about racism more generally, as “race-obsessed scholars and activists” who “accus[e] everybody of being racist by not foregrounding race,” viewing everything else in society through the lens of their obsession. However, when you read the full paper—something Lindsay apparently doesn’t think his audience will do—it becomes obvious that this isn’t the full story. What Ladson-Billings and Tate actually argue is simply that race is “a significant factor in determining inequity in the United States,” especially in matters of education, and that “class- and gender-based explanations are not powerful enough to explain all the difference” by themselves. Race is “central,” not in the sense that it’s the “fundamental organizing principle of society,” but in the sense that many other categories are impacted by it in some way, and it’s impossible to reach a full understanding of the issue at hand (in this case, education) without taking race into consideration. Elsewhere in the paper, the authors state that “issues of gender bias also figure,” and that “Marxist and Neo-Marxist formulations about class continue to merit consideration.” Far from being fixated on race as their sole concern, they display a nuanced understanding of the interrelatedness of different social issues, framing racism as a significant “organizing principle,” but hardly the “fundamental” one. There’s a glaring disconnect between the simplistic caricature Lindsay puts forward and the actual tenets of the theory he’s talking about—a theme that recurs throughout Race Marxism.

The first definition, though, is the really wild one. With its ominous reference to “everything you want to control,” it asserts that critics of contemporary racism are not actually motivated by a concern for justice or equality, but by a sinister agenda to gain political dominance at any cost. “Seizing power,” we’re told, is “the central, but hidden, interest of Critical Race Theorists,” and “it is not on behalf of these ‘minoritized’ racial groups at all that Critical Race Theorists do their work.” Instead, “What its proponents are chiefly interested in is increasing power for themselves.” Lindsay seizes on Ibram X. Kendi, the Director of the Center for Antiracist Research at Boston University and author of How to Be An Antiracist, as one of these power-hungry figures, citing Kendi’s 2019 proposal to create a “Department of Anti-racism” within the U.S. government:

[…] [R]acism could be ended, in theory, by a combined total Racial Bolshevik Revolution and Antiracist Cultural Revolution led by Critical Race Theorists, presumably mediated through the proximate stage by a Dictatorship of the Antiracists paralleling Marx’s notion of a Dictatorship of the Proletariat. This claim sounds extreme, but when we consider that Ibram X. Kendi has called for an antiracist constitutional amendment that would install a new unaccountable branch of government with exactly that power, it becomes clear.

In fact, it’s anything but clear. What Kendi actually proposed in 2019 was to create a body of “formally trained experts on racism” (not a “branch of government”) who would “be responsible for preclearing all local, state and federal public policies to ensure they won’t yield racial inequity,” in much the same way that the Congressional Budget Office audits proposed spending plans to prevent them from causing deficits. The idea is slightly idiosyncratic, and it’s not clear how it would actually work in practice; Kendi himself describes it as “completely out of left field” and says it was created for a POLITICO series on “How to Fix Inequality” that included many other hypothetical scenarios. Lindsay, though, sees a “Dictatorship of the Antiracists” as an imminent, all-consuming threat:

[…] [E]very school, college, university; every workplace, office, hospital; every magazine, journal, newspaper; every television program, movie, website; every government agency, institution, program; every church, synagogue, mosque; every club, affinity, pastime and interest must be turned bit by bit into a means by which critical race consciousness can be induced in the people who participate in it by any means whatsoever. If this can be done by desire, that’s best. If not, there’s coercion and extortion, usually of the moral or public relations sorts. If that’s not enough, as Kendi’s Department of Anti-racism ambitions reveal, there’s political force. If that’s still not enough—one hopes against hope this won’t come to pass—there’s Mao Zedong’s famous dictum: “political power flows from the barrel of a gun.”

Again, we can see the disconnect at work. One college professor floats the idea of a government agency that oversees new policies to make sure they aren’t racist, and from that, Lindsay spins a febrile vision of dystopia, in which Ibram X. Kendi is the next Mao Zedong, poised to enact a “total Racial Bolshevik Revolution” over everything and everyone. It’s an incredibly histrionic reaction, and it reveals the kind of work that Race Marxism actually is. Despite the book’s academic pretensions, what we’re dealing with isn’t political theory, but conspiracy theory, which wildly accuses people of all sorts of underhanded scheming with little or nothing in the way of evidence. The difference between the two is that conspiracy theories are unfalsifiable; we can’t prove or disprove, for example, whether ancient Egyptians had contact with aliens or if Stanley Kubrick hid secret messages in Eyes Wide Shut. The same is true for Lindsay’s ideas about “seizing power” being the “central, but hidden” aim of antiracist activism, which remain speculation at best, and melodramatic persecution fantasies at worst.

The irony, though, is that Lindsay—having spun his tale about the “Dictatorship of the Antiracists”—immediately turns around and claims that antiracists themselves are the ones who are paranoid and delusional:

Put more simply, Critical Race Theory can be understood to be a vast conspiracy theory which argues that white people, both historically (which has some truth behind it) and into the present (which does not), have organized society specifically so that it produces disparate racial outcomes (“systemic racism”) that advantage themselves over everyone else, especially blacks. It is therefore worth highlighting that the emphasis in my definition of Critical Race Theory is placed on the word “belief” because its view of the world requires an inordinate amount of dark and pessimistic faith.

There are several remarkable things about this passage. First, Lindsay acknowledges that systemic racism once existed in the United States—this “has some truth behind it.” It would be hard to claim otherwise, since the history of slavery, segregation, and Jim Crow is so well-documented; even Joe Biden, our current president, grew up in a world where “FOR WHITES ONLY” signs were a common sight. But while he’s forced to concede the obvious about the past, Lindsay immediately rebounds, claiming that the charge of systemic racism today “does not” contain any truth. This presents an interesting question: at what point, exactly, does he think the racism went away? Was it in 1964, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act? In 2008, when Barack Obama was elected President? Or maybe in 2022, when the State of Tennessee officially voted to outlaw all forms of slavery? No matter which date he picked, he’d be wrong; just by turning on the news, we can find plenty of examples of systemic racism.

In Los Angeles alone, several members of the city council were recently recorded using a torrent of racial slurs and insults, describing a Black child as being “like a monkey” and disparaging a district attorney for being “with the Blacks.” Meanwhile, the LAPD contains flourishing white supremacist gangs who call themselves things like “the Lynwood Vikings” and “the Grim Reapers,” and get “998” tattoos to celebrate police killings of civilians. These could, at a stretch, be written off as merely “bad apples,” so let’s go further: a 2020 survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation, hardly a left-wing institution, found that 71 percent of Black Americans have “experienced some form of racial discrimination or mistreatment during their lifetimes,” including 48 percent who “felt their life was in danger because of their race,” compared to only 23 percent of white Americans. In the field of medicine, a 2019 CDC study found that Black women are over 3 times more likely to die of pregnancy or its complications than white women, despite “no significant differences in preventability by race/ethnicity” other than access to quality healthcare. American prisons commonly ban books by Black activists like Marcus Garvey and Angela Davis, but decline to ban Mein Kampf. Systemic racism is not only real, it’s blatantly obvious, and it’s lethal. So it doesn’t take a “dark and pessimistic faith” to conclude that a system which routinely produces racist incidents and outcomes is itself racist. Instead, it would take a startling amount of naivety—or willful ignorance—to deny it.

This still leaves a key question unanswered, though: in what sense does Lindsay think Critical Race Theory (and/or antiracism) are “Marxist”? It’s the title of the book, after all, and the cornerstone of his claim that there’s a “one-hundred-year-long spear that is being thrust into the side of Western civilization.” (Paging Dr. Freud!) Here, Race Marxism turns its attention to a favorite conservative bogeyman: the Frankfurt School.

For the unfamiliar, the Frankfurt School was a loose collection of Marxist intellectuals who originally worked at Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany, before dispersing to various parts of the world during Hitler’s rise to power. The most famous figures from this “school” included Walter Benjamin, Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse, all of whom were broadly interested in expanding the scope of Marxist theory to the field of mass culture. Where Marx and Engels wrote about the exploitation of the working class in the factories of Europe, the Frankfurt school examined the role of music, film, poetry, advertising, and other cultural forms in the ongoing class struggle. (This is the source of Lindsay’s distinction between “Marxism” and “neo-Marxism,” which, like many things in Race Marxism, is grossly historically inaccurate. Marxists have always been interested in culture; it’s just that, with the advent of things like radio and television, there was suddenly a lot more culture for the Frankfurt School to analyze, and they responded accordingly.) For reasons of space, this is a quick-and-dirty outline of the work of some highly sophisticated scholars; a much fuller exploration can be found in Stuart Jeffries’ Grand Hotel Abyss: The Lives of the Frankfurt School, which is worth a read for anyone interested in the subject.

On the Left, the Frankfurt School was (and is) controversial. The Frankfurt theorists are often seen as overly pessimistic in their analysis, and they produced some notoriously goofy ideas, like Adorno’s hatred of jazz, or his personality quiz to detect potential fascists. On the Right, though, they’re seen in a much different light, as dangerous subversives whose ideas pose an existential threat to “Western” society. Because many of its members were Jewish men, the Frankfurt School has become a nexus of antisemitic conspiracy theories about “Cultural Marxism.” As described by the Southern Poverty Law Center (far from a perfect institution itself, but here an accurate one) the “Cultural Marxism” narrative identifies “Jews in general and several Jewish intellectuals in particular as nefarious, communistic destroyers” who attempt to subvert American society by “convinc[ing] mainstream Americans that white ethnic pride is bad, that sexual liberation is good, and that supposedly traditional American values—Christianity, ‘family values,’ and so on—are reactionary and bigoted.” The term itself derives from the Nazi word kulturbolschewismus, or “Cultural Bolshevism,” and in the United States, Marcuse in particular is often singled out as one of these “nefarious, communistic destroyers.” In 1968, then Governor Ronald Reagan was instrumental in a pressure campaign to get Marcuse dismissed from his job at the University of California San Diego, which failed; in 1969, “Marxist Marcuse” was hanged in effigy by protestors at San Diego’s City Hall, providing the memorable opening image for the documentary Herbert’s Hippopotamus. Even John Wayne, of all people, complained about Marcuse in a 1971 interview for Playboy, saying that if anyone didn’t find his “articulate clique” threatening, it was because “their kid hasn’t been inculcated yet.” Marcuse also received death threats from the Ku Klux Klan, which gave him “seventy-two hours to leave the United States”; with typical good humor, he replied that “If somebody really believes that my opinions can seriously endanger society, then he and society must be very badly off indeed.”

This is the historical background that Race Marxism emerges from, and true to form, Lindsay zeroes in on the Frankfurt School, Marcuse, and “Cultural Marxism” as the arch-villains of his piece. To his credit, he acknowledges that the term “Cultural Marxism” has antisemitic connotations—well, sort of:

Here we meet a pressing aside. The term “cultural Marxism” is fraught because the neo-Marxists were extremely effective at getting it branded as an “antisemitic conspiracy theory” (with themselves as the alleged conspirators against the West—which is actually true, but not because they were Jewish).

So for the moment, let’s be charitable, and take him at his word: he’s not actually peddling antisemitic rhetoric, he just happens to be attacking a group of Jewish intellectuals as “conspirators against the West” for purely unrelated reasons. In any case, he begins by saying that Critical Race Theory is “directly in line with Max Horkheimer’s vision for what a critical theory is meant to accomplish”—that is, to analyze the existing culture with the eventual goal of creating “a fundamentally different society,” in this case a non-racist one. This is actually reasonable enough, although he insists on calling critical theories “those evil things bearing the analogous proper-noun designation born in Frankfurt in the service of Marxism,” which is a bit dramatic. The narrative quickly turns, though, to the accusation that “it is not on behalf of these ‘minoritized’ racial groups at all that Critical Race Theorists do their work,” and that “seizing power” is the real aim, and this is where Marcuse comes in:

Marcuse effectively complains that advanced capitalism has been too successful at producing a prosperous, flourishing society and a healthy middle class, with the result being that the working class has lost its revolutionary spirit. He then seeks a new location for the radical revolutionary spirit and finds it in “the ghetto populations,” notably the Black Liberation movements. If these can be channeled into a critical consciousness by Marcuse’s leftist intelligentsia in the universities, […] a new revolutionary proletariat could emerge that has the necessary energy to successfully push Western societies into socialism. In a major respect, Critical Race Theory grew out of this explicitly neo-Marxian project.

Here we have the core of the conspiracy theory: that a “leftist intelligentsia,” with Marcuse and the other Frankfurt theorists as foundational figures, is “channeling” movements for racial justice and liberation, with the goal of “pushing Western societies into socialism.” Or, to approach it from the opposite end: prominent movements for racial justice are not actually about the things they claim to be about, but are manifestations of the “neo-Marxian project” to overthrow society and seize power.

This is all, to put it mildly, a bit of a mess, and it’s hard to know where to begin a critique. Race Marxism is one of those books that contains many individual points that sound superficially convincing, but never coheres into a single clear argument from start to finish. The narrative jumps wildly from one thinker to the next, name-dropping profusely as it goes, and veers off into strange tangents at unexpected times. It’s frustrating to respond to, possibly by design. But as a start, we can point out a few contradictions. At several points, Lindsay claims that Critical Race Theory is “intrinsically revolutionary in its orientation, as its centrally named objective—ending racism and achieving racial justice—can only be accomplished by replacing the system at its very foundations.” This is in keeping with the “fundamental organizing principle” line, which he keeps returning to. However, one of the main examples he gives of Critical Race Theory in action, Kendi’s Department of Antiracism, is supposed to be established through an amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which various state delegates would presumably vote on—using the existing political system, not overthrowing it. This is a fairly major distinction, showing an institutionally liberal political sensibility at work, not a Marxist one; reform, not revolution. Race Marxism is riddled with inconsistencies like this.

In the first place, the idea that the Frankfurt School was fundamentally concerned with “seizing power” doesn’t add up, since during their actual careers, its founders were constantly criticized from the Left for being insufficiently concerned with power struggles. As Stuart Jeffries recounts in Grand Hotel Abyss:

From its inception in 1923, the Marxist research institute that became known as the Frankfurt school was aloof from party politics and sceptical about political struggle. Its leading members […] were virtuosic at critiquing the viciousness of fascism and capitalism’s socially eviscerating, spiritually crushing impact on western societies, but not so good at changing what they critiqued.

Specifically, most of these theorists were active in 1968, when university students around the world rose up in revolt against the Vietnam War, institutional racism, and other injustices, and often physically took control of university campuses and buildings, including (briefly) the sociology department of the University of Frankfurt. Many people believed a revolutionary situation was brewing in Europe, and if they were truly obsessed with “seizing power,” you might expect people like Horkheimer, Marcuse, and Adorno to be at the front lines. Instead, as Jeffries chronicles, they opted for a “retreat into theory,” wary of “authoritarian personalities” in these new youth movements, and Adorno told a German newspaper that he had merely “established a theoretical model of thought. How could I have suspected that people would want to implement it with Molotov cocktails?” (For his troubles, he was harassed by the Communist students on campus, who heckled his lectures and wrote, “If Adorno is left in peace, capitalism will never cease!” on his blackboards.)

In general, if you want to seize power, about the worst tactic you could adopt is to write long tomes of academic theory that require a glossary of philosophical jargon to understand, especially at a moment when there’s a real live class struggle happening outside your window. (Seriously, try reading Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man, or Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment; they’re interesting books, and sometimes insightful, but dear God are they dense.) If you have even a passing familiarity with it, the reality of the Frankfurt School is so far from Lindsay’s conspiratorial depiction that Race Marxism just ends up looking ridiculous. The evidence he gives to connect current antiracist activism to Frankfurt doesn’t help, either; one of the lynchpins of this connection is the fact that Angela Davis, the pioneering prison abolitionist, was Marcuse’s graduate student, and “receives extensive praise” in Kendi’s book Stamped from the Beginning, drawing a sort of six-degrees-of-Kevin-Bacon connection between the three. Compared to the gravity of the claims being thrown around—remember, we’re talking about a “total racial Bolshevik revolution,” which might flow “from the barrel of a gun”—this is thin stuff.

Not to worry, though; if you don’t find Lindsay’s beliefs convincing, he has others. Having accused Critical Race Theorists of being devious European Cultural neo-Marxists, he wants you to know that they’re also Nazis. For this eyebrow-raising claim, he reaches back to W.E.B. Du Bois, who he calls the “philosophical godfather of Critical Race Theory,” and fixates on the way he used the word “folk,” as in the titles of his books The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and The Gift of Black Folk (1924). Now, it’s true that Du Bois was influential on the pioneering thinkers of Critical Race Theory, many of whom cite his idea of “double consciousness”—an acute awareness of being simultaneously “American” and “Black”—as foundational to their understanding of the way different identities combine and overlap in a racialized society. But to Lindsay, the word “folk” means—and this is his actual claim—that Du Bois espoused a “Völkisch” ideology similar to that of the German Nazi Party:

This mode of thought is considerably important to understanding the otherwise odd word “folks” in Critical Race Theory, which constantly refers to “black folks,” “white folks,” and “brown folks” (and any of the above “folx” if intersectionality queer at the same time.) The Volk, in German, is the relevant “folks” here, and it refers to a people or a nation bound by similar cultural heritage. Critical Race Theory, largely following from Du Bois, is very racially folkish (that is, Völkisch).

Elsewhere, he elaborates:

I do not think Critical Race Theory can be understood without realizing it seeks to establish a racial Völkisch nationalism in which “patriotic” members have considerable investment.

Here, if you squint, there’s a grain of truth among the nonsense. Antiracist struggles have sometimes intersected with racial nationalism—consider Malcolm X’s stint in the Nation of Islam—and some theorists of race have described “Blackness” as a pseudo-national political identity rather than a straightforwardly ethnic one. (For example, members of the Black Panther Party often described America’s Black population as an “internal colony,” separate from and struggling against the domination of the United States.) In this vein, Lindsay decries the way some self-described antiracists attempt to strip “Blackness” from individuals they consider “no longer authentic representatives of their race,” such as conservative radio host Larry Elder (“nicknamed the ‘black face of white supremacy’ by the Los Angeles Times while running for governor”) or Kanye West (“no longer to be considered ‘Black,’ according to Ta-Nehisi Coates, after he donned a ‘Make America Great Again’ hat”). Not all of the examples land—the Coates essay in question actually speculates that West wants to discard his own Blackness, which is different—but Lindsay is gesturing at a real phenomenon here; like with any identity, the political dimensions of Blackness are contested, and open to abuse. Probably the most glaring example in recent memory came when Joe Biden (himself a segregationist, once upon a time) declared that “If you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump, then you ain’t black,” demanding racial “patriotism” purely for his own benefit. But even taking all this into account, the invocation of Nazi Germany is grotesquely inappropriate and offensive, since there’s a colossal difference between racial nationalism among historically oppressed minority groups, and by a genocidal invading empire. It ruins what could, in isolation, have been Race Marxism’s sole good point.

The “no, you’re the real Nazis” maneuver isn’t new, of course. If anything, it’s something of a hack move by this point, having worn out its welcome with Dinesh D’Souza’s equally ridiculous 2017 book The Big Lie: Exposing the Nazi Roots of the American Left. This doesn’t stop Lindsay from trying to defend the point, of course, and his rationale forms one of the book’s most startling moments:

The way this aspect manifests is through racial scapegoating of whites, who are automatic beneficiaries of “whiteness,” as mentioned elsewhere in the book. The racial scapegoating rooted in whiteness parallels the Nazi scapegoating of Jews almost perfectly, in fact. Unlike in the previous point, there’s not much daylight between Marxism and Nazism here. In both ideologies, the point of the scapegoating, by race for Hitler and by class for Marx, is to seize the property of and ultimately abolish those seen as the usurping class of society. In Critical Race Theory, this is explicitly racial, however, which is a point that Hitler hammers home repeatedly (and with tremendous racism) throughout Mein Kampf.

Let’s take a moment to fully comprehend what’s being said here—that critics of racism, who think and talk about the way racial biases work in society, are “scapegoating” white people in the same way Hitler did to the Jews of Germany, simply by identifying white people as having benefited from racism. White people, not minorities getting denied medical care or harassed by the cops, are the real victims here, because they’ve been dubbed a “usurping class,” and if Critical Race Theory is left unchecked—this is the unavoidable implication—they might have their property seized, and find themselves “abolished,” presumably through violence. This is a hell of a thing to say without concrete evidence, and ironically, it holds disturbing echoes of the “white genocide” conspiracy theory espoused by actual Nazis. It’s also historically illiterate; as countless people have pointed out by now, Marxism and Nazism are not comparable ideologies, but entirely opposed ones, and Marxists, especially Jewish ones, were among the first victims of Hitler’s regime. This is the whole reason Marcuse, Adorno, and Horkheimer had to flee Frankfurt—but then, if Lindsay’s claims about their intentions were true, the Nazis might actually have had a point in persecuting them as subversives! It’s difficult to see how these passages don’t eventually boil down to white nationalist talking points, and it’s frankly a repulsive and unnerving experience.

So, to recap, Lindsay says Critical Race Theory and antiracism are:

- A paranoid conspiracy theory (because systemic racism doesn’t exist)

- A dangerous conspiracy dreamed up by Marcuse and Co.

- “Cultural Marxism”

- “Racial Völkisch nationalism”

- Nazism

None of these explanations are compatible with each other, but then, making logical sense doesn’t seem to be the point. Race Marxism just wants to convince you that critics of racism are bad, and it’ll seize on any pretext to reach that conclusion. (There’s a whole other section of the book where Lindsay claims Critical Race Theory is also a Gnostic religion, but I’ll leave that as a surprise for the reader.) And because this stuff is supposed to be so evil, Race Marxism devotes its sixth and final chapter to the measures that might be necessary to get rid of it.

This is where Lindsay lays his cards on the table, proposing an actual plan of action. Some parts of his advice are fairly benign, like when he exhorts his readers to “Speak plainly, honestly, and from genuine morals,” which is supposed to neutralize the “crooked terminology” of antiracism. Others, however, amount to little more than reheated McCarthyism and a new Red Scare, like when he urges that “Critical Theorists are to be removed from positions of power and influence or limited in their ability to apply Critical Theory through them—ideally by force of law.” Showing some self-awareness, he acknowledges that these measures may be seen as “backlash, authoritarianism, or even rising fascism,” but concludes that it’s ultimately worth it; the people in question, he reiterates, “must be fired, forced to resign, voted out of office, sued, defunded, and limited in their ability to abuse power for Critical means by both law and institutional policy.” In order to do this, his readers must be “willing to take on civic responsibility like serving in local government or on institutional boards.”

There’s also a legal strategy, which Lindsay envisions as starting with “small, easily winnable cases” demanding “a narrower interpretation of discrimination” in the courts, eventually building up to bigger cases in which “this more specific understanding of discrimination law (intention matters) is applied in a color-neutral fashion (no protected classes).” This, he says, would “defang much of Critical Race Theory in a single swoop” (by stripping protections from people and making it easier to do and say racist things), and he encourages his readers to “Start thinking of yourself as a potential plaintiff here.” Of course, Lindsay doesn’t see any of this as an attempt to “seize power” to enforce a particular agenda; his beliefs, after all, are just The Way Things Are Supposed to Be. But it amounts to a stated goal to shred the First Amendment and set up a regime of state-sanctioned discrimination based on political beliefs, where only people who agree with Lindsay’s views on race can work in certain fields, and anyone accused of believing in “Critical Race Theory” is blacklisted as an official enemy.

It’s ironic that Lindsay’s publishing house is called “New Discourses,” because Race Marxism contains virtually nothing new at all. Instead, like some noxious mother bird, it simply half-digests a bunch of reactionary tropes and concepts from the past hundred years, and regurgitates them onto the page. In its terms, antiracists are the real racists, the subjects of conspiracy theories are the real conspiracy theorists, white people are the victims, and minorities who notice their oppression are the oppressors. Worse, the words “Marxism” and “Critical Race Theory” are warped beyond recognition, erasing the history of countless people who have used both to oppose very real injustices.

In his opening definitions, Lindsay says the hallmark of his ideological enemies is to call everything racist, so I’ll refrain from doing so. I have no idea whether he’s personally racist, and don’t particularly care. But when you write a 310-page book about how evil antiracists are, and offer a practical plan for how to run them out of public life, the effect of your actions is to make the world a more comfortable place for racists, whatever your intentions may have been. It’s a bit perverse, too, to choose Critical Race Theory as the issue most worthy of your attention, in a world with so many other crises and horrors. Lindsay desperately wants Race Marxism to be seen as a Dangerous Text the Left Doesn’t Want You to Read, but the opposite is true: it would be no bad thing if lots of people read this book, listen to its author talk, and ask themselves whether it makes any sense at all. The more people see of James Lindsay and his arguments, the less persuasive they’ll find them, and the more sympathy they’ll have for his targets.