“Forget They Are an Animal”

Animal agriculture articles from the 1970s reveal how the industry has always thought of animals: as nothing more than profit-generating machines.

Reporting on animal agriculture, I think a lot about euphemisms. Any time the meat industry describes things one way, there’s a good chance the reality is the 180-degree opposite. Diabolical torture methods are called “euthanasia.” Caging pregnant pigs in crates so small they can barely move is said to reduce stress and promote their welfare. These industry lies are banal and unsurprising. But sometimes they’re so obscene that they almost appear designed to mock the idea that, when it comes to nonhuman animals, the truth has any meaning at all.

Take this Orwellian “We ♥ moms” advertisement:

This campaign was created by the Indiana-based company United Animal Health, whose name is itself a euphemism. As an “animal science” research firm, its mission is to “create value for livestock producers.” In the pork industry, “sow research” means engineering female pigs to give birth to as many viable piglets as possible throughout their lives. Each mother pig on a typical factory farm is immobilized in a tiny cage, artificially inseminated, and forced to give birth to litter after litter of baby pigs, who are promptly taken away and slaughtered at about six months old.

In his book Porkopolis, anthropologist Alex Blanchette explains that one consequence of pushing pig pregnancies to their limit has been “litters that are too large to supply adequate nutrients to fetuses in the uterus”—in other words, litters full of ailing runts. “[I]t appears to be near-impossible in the industry to encounter a conceptual or ethical limit proposed for sows’ biological reproductive capacity,” Blanchette writes. “The idea that litter sizes must interminably grow has become so taken for granted that even animal welfare scientists—those most concerned with the pig’s bodily integrity—have taken a central measure of humane farming conditions to be whether the sow reproduces at high levels.” The point of all this is to extract ever more value from the body of each animal, which matters for an industry that has relatively little growth potential in the U.S. “An average of one extra pig per litter in corporations that own 100,000 sows—which would allow them to house fewer sows—means that they can save $25 million per year,” Blanchette writes.

How does raw greed come to be portrayed as love? Today’s consumers—who are mostly urban, have little direct experience with agriculture, and have heard vaguely disturbing mentions of “factory farming”—want to be told that the animals they eat were treated nicely, like family. They need to be convinced that what’s good for business is good for animals. I believe this is even shaping how some people within the factory farm industry see their roles. Helping to bring life into the world, no matter how perverse the system it’s born into, can create a genuine sense that what you’re doing is nurturing, providing a kind of care. So we end up with absurd narratives like “We ♥ moms” and “Here, every day is Mother’s Day.” According to the pork industry, “love” means “we lock you up and take your babies and kill you.” All this in the name of turning animals into cheap hot dog filling.

It can be vertigo-inducing to imagine what was going through the mind of the person who designed that advertisement, which, I think, is exactly the point. Fascist propaganda can’t be reasoned with; it’s meant to put forth a fraudulent reality that makes you question your own sanity.

A few months ago, I came across a different kind of meat industry propaganda. A 2014 Washington Post op-ed by Matthew Prescott, an advocate with the Humane Society of the United States, quoted two prominent pork industry magazines from the 1970s:

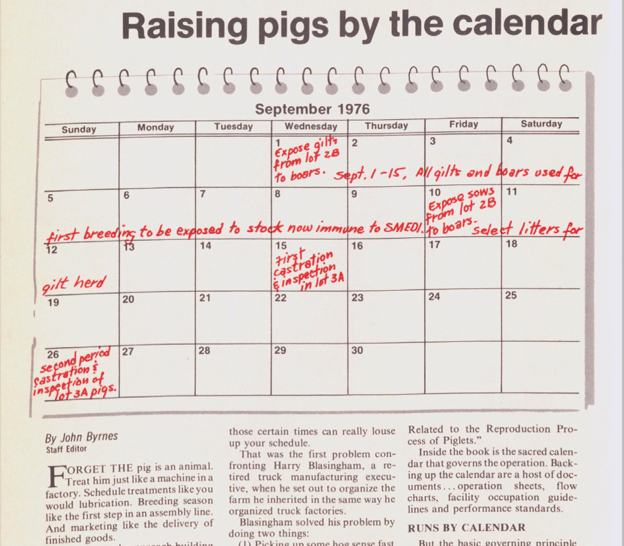

- “Forget the pig is an animal—treat him just like a machine in a factory,” recommended Hog Farm Management in 1976.

- “The breeding sow should be thought of, and treated as, a valuable piece of machinery whose function is to pump out baby pigs like a sausage machine,” National Hog Farmer advised two years later.

These quotes seemed unbelievable, and part of me doubted that they were real. A lot has changed since the ’70s, but were things really so different that pork producers communicated this way? Here, out in the open, was exactly what animal rights activists have long said the meat industry really thinks about animals. So I sought out the original copies of these journals. (One of them, National Hog Farmer, is still publishing and is where I first saw the “We ♥ moms” ad this past April.)

Sure enough, right in the lede, this article from the September 1976 issue of Hog Farm Management encouraged farmers to “forget the pig is an animal” and “treat him just like a machine.” There is no subtlety here: Readers are instructed to “use the same principles in hogs as in organizing industry,” viewing their animals as “widgets” and managing their reproduction on a rigid, calendarized basis. For help with this, farmers need look no further than PREG-ALERT, a technology conveniently advertised in the middle of the article:

With PREG-ALERT, you can “cull out the feed wasters”—pigs who aren’t making enough babies—and “concentrate on your big producers.”

In the second article, from March 1978’s National Hog Farmer, a British meatpacking executive urges his American counterparts to systematize pigs’ reproduction with artificial insemination (too many farmers just put a boar in with their female pigs and hope it ends in pregnancy!), a practice tantamount to bestiality that’s now meat industry standard. And then the infamous quote, which is cited in texts including Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation: “The breeding sow should be thought of, and treated as, a valuable piece of machinery whose function is to pump out baby pigs like a sausage machine.”

You’d never see industry sources talking openly about animals this way today. In the ’70s, only people in animal agriculture would have been reading these journals, but the context collapse created by the internet means the industry now needs to be much more careful about what it says. Entire marketing budgets are devoted to convincing the public that industrial animal farming is a business of love and care.

The articles reflect a time when more than a third of Americans were rural and unoffended by describing farm animals as exactly what they are: commodities. It was also when the factory farmification of the pork industry was quickly taking off, so talking about animal agriculture as just like any industrial process would have sounded novel and interesting, rather than, as many consumers now see it, dystopian.

I was reminded of historian Caitlin Rosenthal’s work on the economics of slavery, the chilling feeling I got reading about how plantation records rendered enslaved people as inputs, meticulously tracking their productivity and “depreciation.” “Systematic accounting practices thrived on antebellum plantations—not despite the chattel principle, but because of it,” Rosenthal writes. Reducing lives to units on a spreadsheet obviously results in horrors, but when you’re running a business, it’s simply rational. This is what it means to commodify lives.